Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Brass Teacherõs Guide

Teacher’s Guide Brass ® by Robert W.Getchell, Ph. D. Foreword This manual includes only the information most pertinent to the techniques of teaching and playing the instruments of the brass family. Its principal objective is to be of practical help to the instrumental teacher whose major instrument is not brass. In addition, the contents have purposely been arranged to make the manual serve as a basic text for brass technique courses at the college level. The manual should also help the brass player to understand the technical possibilities and limitations of his instrument. But since it does not pretend to be an exhaustive study, it should be supplemented in this last purpose by additional explanation from the instructor or additional reading by the student. General Characteristics of all Brass Instruments Of the many wind instruments, those comprising the brass family are perhaps the most closely interrelated as regards principles of tone production, embouchure, and acoustical characteristics. A discussion of the characteristics common to all brass instruments should be helpful in clarifying certain points concerning the individual instruments of the brass family to be discussed later. TONE PRODUCTION. The principle of tone production in brass instruments is the lip-reed principle, peculiar to instruments of the brass family, and characterized by the vibration of the lip or lips which sets the sound waves in motion. One might describe the lip or lips as the generator, the tubing of the instrument as the resonator, and the bell of the instrument as the amplifier. EMBOUCHURE. It is imperative that prospective brass players be carefully selected, as perhaps the most important measure of success or failure in a brass player, musicianship notwithstanding, is the degree of flexibility and muscular texture in his lips. -

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN and HIS CONTRIBUTION to the ART of TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFRE

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFREY SHAMU A.B. cum laude, Harvard College, 1994 M.M., Boston University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2009 © Copyright by GEOFFREY SHAMU 2009 Approved by First Reader Thomas Peattie, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Music Second Reader David Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Music Third Reader Terry Everson, M.M. Associate Professor of Music To the memory of Pierre Thibaud and Roger Voisin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this work would not have been possible without the support of my family and friends—particularly Laura; my parents; Margaret and Caroline; Howard and Ann; Jonathan and Françoise; Aaron, Catherine, and Caroline; Renaud; les Davids; Carine, Leeanna, John, Tyler, and Sara. I would also like to thank my Readers—Professor Peattie for his invaluable direction, patience, and close reading of the manuscript; Professor Kopp, especially for his advice to consider the method book and its organization carefully; and Professor Everson for his teaching, support and advocacy over the years, and encouraging me to write this dissertation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Voisin family, who granted interviews, access to the documents of René Voisin, and the use of Roger Voisin’s antique Franquin-system C/D trumpet; Veronique Lavedan and Enoch & Compagnie; and Mme. Courtois, who opened her archive of Franquin family documents to me. v MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING (Order No. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Download This Composer Profile Here

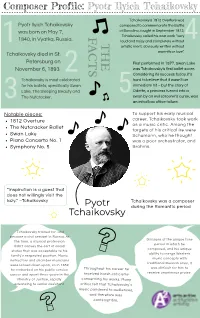

Composer Profile: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed to commemorate the Battle was born on May 7, of Borodino, fought in September 1812, F Tchaikovsky called his own work “very 1840, in Vyatka, Russia. loud and noisy and completely without THE A 4 1 artistic merit, obviously written without Tchaikovsky died in St. CTS warmth or love”. Petersburg on First performed in 1877, Swan Lake November 6, 1893. was Tchaikovsky’s first ballet score. 2 Considering its success today, it's Tchaikovsky is most celebrated hard to believe that it wasn’t an for his ballets, specifically Swan immediate hit – but the story of Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and Odette, a princess turned into a The Nutcracker. 5 swan by an evil sorcerer's curse, was 3 an initial box office failure. Notable pieces: To support his early musical 1812 Overture career, Tchaikovsky took work as a music critic. Among the The Nutcracker Ballet targets of his critical ire were Swan Lake Schumann, who he thought Piano Concerto No. 1 was a poor orchestrator, and Symphony No. 5 Brahms. “Inspiration is a guest that does not willingly visit the lazy.” –Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky was a composer I'mPy oOtrne! during the Romantic period Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky trained for, and became a civil servant in Russia. At Because of the unique time the time, a musical profession period in which he didn’t convey the sort of social composed, and his unique status that was acceptable to his ability to merge Western family’s respected position. Music music concepts with instructors and chamber musicians traditional Russian ones, it were looked down upon, so in 1859 was difficult for him to he embarked on his public service Throughout his career he receive unanimous praise. -

Care & Maintenance

Care and Maintenance of the Euphonium and Piston-Valve Tuba You Will Need: 1) Soft cloth (cotton or flannel) 4) Valve brush 2) Flexible brush (also called a “snake”) 5) Tuning slide grease 3) Mouthpiece brush 6) Valve Oil Daily Care 1) Never leave your instrument unattended. It takes very little time for someone to take it. 2) The safest place for your instrument is in the case. Leave it there when you’re not playing. 3) Do not let other people use your instrument. They may not know how to hold and care for it. 4) Do not use your case as a chair, foot rest or step stool. It is not designed for that kind of weight. 5) Lay your case flat on the floor before opening it. Do not let it fall open. 6) Do not hit your mouthpiece, it can get stuck. 7) Do not lift your instrument by the valves. Use the bell and any large tubes on the outside edge. 8) No loose items in your case. Anything loose will damage your instrument or get stuck in it. 9) Do not put music in your case, unless space is provided for it. If you have to fold it or if it touches the instrument, it should NOT be there. 10) Avoid eating or drinking just before playing. If you do, rinse your mouth with water before playing. 11) You may not need to do it every day, but keep your valves running smooth with valve oil. Put the oil directly on the exposed valve, not in the holes on the bottom of the casings. -

Loose Adaptation for Chamber Orchestra (2013, Commissioned by Festival Berlioz) by Arthur Lavandier (Born in 1987)

LE BALCON SYMPHONIE FANTASTIQUE Loose adaptation for chamber orchestra BERLIOZ | LAVANDIER Le Balcon New Label — Le Balcon French national release : September 20th, 2016 CD BOX : TRANSAURAL VERSION – 3D SURROUND MIX FOR LOUDSPEAKERS- DOWNLOAD CODE INCLUDED FOR BINAURAL VERSION -3D SURROUND MIX FOR HEADPHONES Concerts : Théâtre de l’Athénée Sep 24 & 25, 2016 — Festival de Pâques de Deauville Apr 15, 2017 Teatro Mayor Jun 9, 2017 — Théâtre de Carcassonne Dec 8, 2017 — Opéra de Lille Mar 25, 2018 press [at] lebalcon.com PRESENTATION Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) Symphonie fantastique op. 14 (1830) Loose adaptation for chamber orchestra (2013, commissioned by Festival Berlioz) by Arthur Lavandier (born in 1987) In commissioning the Balcon ensemble for an ‘interpretation’ of the Symphonie Fantastique, the Festival Berlioz took a considerable risk. Given the size of the orchestra, a ‘transcription’, an ‘adaptation’ was necessary or in Arthur Lavandier’s words a ‘recreation’ – a term that we will retain since it was he who undertook this hazardous task. It is not a case of Berlioz against Lavandier, and the contrary even less so. It is an ‘encounter of a third kind’, a mosaic challenge, an open-minded tribute, an orchestral game, and shared laughter despite the centuries that divide them both. We could also say that it was like a fan- tasy film re-make. LE BALCON CONDUCTOR, MAXIME PASCAL PRODUCTION AND EDITORIAL CONCEPT, FLORENT DEREX SOLO VIOLIN, YOU JUNG HAN FLUTE, CLAIRE LUQUIENS OBOE, YE CHANG JUNG CLARINET, IRIS ZERDOUD BASSOON, JULIEN ABBES -

Gardiner's Schumann

Sunday 11 March 2018 7–9pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT GARDINER’S SCHUMANN Schumann Overture: Genoveva Berlioz Les nuits d’été Interval Schumann Symphony No 2 SCHUMANN Sir John Eliot Gardiner conductor Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Recommended by Classic FM Streamed live on YouTube and medici.tv Welcome LSO News On Our Blog This evening we hear Schumann’s works THANK YOU TO THE LSO GUARDIANS WATCH: alongside a set of orchestral songs by another WHY IS THE ORCHESTRA STANDING? quintessentially Romantic composer – Berlioz. Tonight we welcome the LSO Guardians, and It is a great pleasure to welcome soloist extend our sincere thanks to them for their This evening’s performance of Schumann’s Ann Hallenberg, who makes her debut with commitment to the Orchestra. LSO Guardians Second Symphony will be performed with the Orchestra this evening in Les nuits d’été. are those who have pledged to remember the members of the Orchestra standing up. LSO in their Will. In making this meaningful Watch as Sir John Eliot Gardiner explains I would like to take this opportunity to commitment, they are helping to secure why this is the case. thank our media partners, medici.tv, who the future of the Orchestra, ensuring that are broadcasting tonight’s concert live, our world-class artistic programme and youtube.com/lso and to Classic FM, who have recommended pioneering education and community A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO tonight’s concert to their listeners. The projects will thrive for years to come. concert at the Barbican, as we are joined by performance will also be streamed live on WELCOME TO TONIGHT’S GROUPS one of the Orchestra’s regular collaborators, the LSO’s YouTube channel, where it will lso.co.uk/legacies Sir John Eliot Gardiner. -

Tchaikovsky.Pdf

Tchaikovsky CD 1 1 Orchestrion It wasn’t unusual, in the middle of the 19th century, to hear sounds like that coming from the drawing rooms of comfortable, middle-class families. The Orchestrion, one of the first and grandest of mass-produced mechanical music-makers, was one of the precursors of the 20th century gramophone. It brought music into homes where otherwise it might never have been heard, except through the stumbling fingers of children, enduring, or in some cases actually enjoying, their obligatory half-hour of practice time. In most families the Orchestrion was a source of pleasure. But in one Russian household, it seems to have been rather more. It afforded a small boy named Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky some of his earliest glimpses into a world, and a language, which was to become (in more senses then one), his lifeline. One evening his French governess, Fanny Dürbach, went into the nursery and found the tiny child sitting up in bed, crying. ‘What’s the matter?’ she asked – and his answer surprised her. ‘This music’ he wailed, ‘this music!’ She listened. The house was quiet. ‘No. It’s here,’ cried the boy – he pointed to his head. ‘It’s here, and I can’t make it go away. It won’t leave me.’ And of course it never did. ‘His sensitivity knew no bounds and so one had to deal with him very carefully. Every little trifle could upset or wound him. He was a child of glass. As for reproofs and admonitions (with him there could be no question of punishments), what would have been water off a duck’s back to other children affected him deeply, and if the degree of severity was increased only the slightest, it would upset him alarmingly.’ Despite his outwardly happy appearance, peace of mind is something Tchaikovsky rarely knew, from childhood to his dying day. -

A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form

MODERN FORMS OF AN ANCIENT ART: A SELECTION OF CONTEMPORARY FANFARES FOR MULTIPLE TRUMPETS DEMONSTRATING EVOLUTIONARY PROCESSES IN THE FANFARE FORM Paul J. Florek, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2015 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Florek, Paul J. Modern Forms of an Ancient Art: A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2015, 73 pp., 1 table, 26 figures, references, 96 titles. The pieces discussed throughout this dissertation provide evidence of the evolution of the fanfare and the ability of the fanfare, as a form, to accept modern compositional techniques. While Britten’s Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury maintains the harmonic series, it does so by choice rather than by the necessity in earlier music played by the baroque trumpet. Stravinsky’s Fanfare from Agon applies set theory, modal harmonies, and open chords to blend modern techniques with medieval sounds. Satie’s Sonnerie makes use of counterpoint and a rather unusual, new characteristic for fanfares, soft dynamics. Ginastera’s Fanfare for Four Trumpets in C utilizes atonality and jazz harmonies while Stravinsky’s Fanfare for a New Theatre strictly coheres to twelve-tone serialism. McTee’s Fanfare for Trumpets applies half-step dissonance and ostinato patterns while Tower’s Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman demonstrates a multi-section work with chromaticism and tritones. -

Hector Berlioz Harold in Italy, Op. 16

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Hector Berlioz Born December 11, 1803, Côte-Saint-André, France. Died March 8, 1869, Paris, France. Harold in Italy, Op. 16 Berlioz composed Harold in Italy in 1834. The first performance was given on November 23 of that year in Paris. The score calls for solo viola and an orchestra consisting of two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and english horn, two clarinets, four bassoons, four horns, two cornets and two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, triangle, cymbals, harp, and strings. Performance time is approximately forty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first performances of Berlioz's Harold in Italy were given on subscription concerts at the Auditorium Theatre on March 11 and 12, 1892 with August Junker as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. At one of the first performances of his blockbuster Symphonie fantastique, Hector Berlioz noticed that a man stayed behind in the empty concert hall after the ovations had ended and the musicians were packing up to go home. He was, as Berlioz recalls in his Memoirs, "a man with long hair and piercing eyes and a strange, ravaged countenance, a creature haunted by genius, a Titan among giants, whom I had never seen before, the first sight of whom stirred me to the depths." The man stopped Berlioz in the hallway, grabbed his hand, and "uttered glowing eulogies that thrilled and moved me to the depths. It was Paganini." Paganini, is, of course, Italian-born Nicolò Paganini, among the first of music's one-name sensations. In 1833, the year he met Berlioz, Paganini was one of music's greatest celebrities, known for the almost superhuman virtuosity of his violin playing as well as his charismatic, commanding presence. -

Les Nuits D'été & La Mort De Cléopâtre

HECTOR BERLIOZ Les nuits d'été & La mort de Cléopâtre SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA ROBIN TICCIATI CONDUCTOR KAREN CARGILL MEZZO-SOPRANO HECTOR BERLIOZ Les nuits d’été & La mort de Cléopâtre Scottish Chamber Orchestra Robin Ticciati conductor Karen Cargill mezzo-soprano Recorded at Cover image The Usher Hall, Dragonfly Dance III by Roz Bell Edinburgh, UK 1-4 April 2012 Session photos by John McBride Photography Produced and recorded by Philip Hobbs All scores published by Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel Assistant engineer Robert Cammidge Design by gmtoucari.com Post-production by Julia Thomas 2 Les nuits d’été 1. Villanelle ......................................................................................2:18 2. Le spectre de la rose .................................................................6:12 3. Sur les lagunes ............................................................................5:50 4. Absence ......................................................................................4:45 5. Au cimetière ...............................................................................5:32 6. L’île inconnue .............................................................................3:56 Roméo & Juliette 7. Scène d’amour ........................................................................16:48 La mort de Cléopâtre 8. Scène lyrique ..............................................................................9:57 9. Méditation.................................................................................10:08 Total Time: ......................................................................................65:48