Balkan Silver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pack 899 Fallston, Maryland

Welcome to Pack 899 Welcome to Pack 899 • Agenda – Introductions – What is Cub Scouting? • Pack Organization • Cub Scout Uniforms • Ranks (Tiger, Cub Scouts, Webelos) • Den Leader Responsibilities – Pack 899 • Events • Calendar What is Cub Scouting? • Started in 1930 by Boy Scouts of America. • Program designed for Boys in 1st through 5th Grade. • Cub Scouting is a year-round family program. • Parents, leaders, and organizations working together to build skills and values that last a lifetime. • Cub Scouting is run by volunteers. Welcome to Cub Scouts Welcome to Cub Scouts • Cub Scouts join a Cub Scout ”Pack” • We are Pack 899 • Our “Chartered Organization” is the: Fallston United Methodist Church 1509 Fallston Road Fallston, Maryland 21047-1624 Welcome to Cub Scouts Scouting is “Fun with a Purpose”. We strive to build these core values through fun activities, games, camping, and fellowship. 1. Citizenship 7. Honesty 2. Compassion 8. Perseverance 3. Cooperation 9. Positive attitude 4. Courage 10. Resourcefulness 5. Faith 11. Respect 6. Health and fitness 12. Responsibility Character is "values in action." Welcome to Cub Scouts • Boys are assigned to a Den, usually a group of six to eight boys. • Dens are led by volunteers (parents). These are your Den Leader (DL) and Assistant Den Leader (ADL). • Dens meet together at least twice a month. Welcome to Cub Scouts • All of our Dens together make up Pack 899. • The Pack is run by parent volunteers consisting of: – Committee Chairman – Cubmaster – Den leaders – Committee Members at large – Special Event Coordinators Welcome to Cub Scouts Welcome to Cub Scouts • The Pack Committee (or just “The Committee”) is the administrative arm of the pack and includes den leaders, parents of boys in the pack, and members of the Chartered Organization. -

MCJROTC UNIFORM STANDARDS A

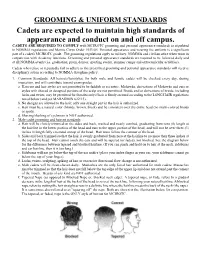

GROOMING & UNIFORM STANDARDS Cadets are expected to maintain high standards of appearance and conduct on and off campus. CADETS ARE REQUIRED TO COMPLY with MCJROTC grooming and personal appearance standards as stipulated in NOMMA regulations and Marine Corps Order 1533.6E. Personal appearance and wearing the uniform is a significant part of a cadet's MCJROTC grade. The grooming regulations apply to military, NOMMA and civilian attire when worn in conjunction with Academy functions. Grooming and personal appearance standards are required to be followed daily and at all NOMMA events (i.e. graduation, prom, dances, sporting events, summer camps and extracurricular activities). Cadets who refuse or repeatedly fail to adhere to the prescribed grooming and personal appearance standards will receive disciplinary action according to NOMMA discipline policy. 1. Common Standards: All haircuts/hairstyles, for both male and female cadets will be checked every day, during inspection, and will contribute toward exam grades. a. Haircuts and hair styles are not permitted to be faddish or eccentric. Mohawks, derivations of Mohawks and cuts or styles with shaved or designed portions of the scalp are not permitted. Braids and/or derivations of braids, including locks and twists, may be permitted for females only if hair is firmly secured according to the LONG HAIR regulations noted below (and per MARADMIN 622/15). b. No designs are allowed to the hair; only one straight part in the hair is authorized. c. Hair must be a natural color (blonde, brown, black) and be consistent over the entire head (no multi-colored braids or spots). d. Shaving/slashing of eyebrows is NOT authorized. -

Mark Standifer's Electrical Safety Briefing

E3948 Mark Standifer’s Electrical Safety Briefing Leader’s Guide © ERI Safety Videos MARK STANDIFER’S ELECTRICAL SAFETY BRIEFING This easy-to-use Leader’s Guide is provided to assist in conducting a successful presentation. Featured are: INTRODUCTION: A brief description of the program and the subject that it addresses. PROGRAM OUTLINE: Summarizes the program content. If the program outline is discussed before the video is presented, the entire program will be more meaningful and successful. PREPARING FOR AND CONDUCTING THE PRESENTATION: These sections will help you set up the training environment, help you relate the program to site-specific incidents, and provide program objectives for focusing your presentation. REVIEW QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS: Questions may be copied and given to participants to document how well they understood the information that was presented. Answers to the review questions are provided separately. INTRODUCTION With nearly 40 years of experience as an electrician, Mark Standifer delivers powerful seminars on the shock and burn hazards associated with electrical work. As a survivor of an arc flash incident, Mark knows the pain and suffering associated with electrical and arc flash injuries. In this live presentation, he stresses the importance of thinking about what we are doing and being aware of all shock and burn hazards when performing electrical job tasks. Mark also makes the point that we must always wear the PPE and FR rated clothing required by the NFPA 70E to protect ourselves from any mistakes that we may make. Viewers will also learn unforgettable lessons about electrical safety from stories about Mark’s incident and his friend’s electrocution. -

Mri Exam Questionnaire to Our Patients and Accompaning Family Members

EL PORTAL IMAGING CENTER Weight: Height: MRI EXAM QUESTIONNAIRE TO OUR PATIENTS AND ACCOMPANING FAMILY MEMBERS... The MR room contains a very strong magnet. Before you are allowed to enter, we must know if you have any metal in your body. Some metal objects can interfere with your scan or may even be dangerous, so PLEASE answer the following questions carefully. If you have a question regarding anything on this form, PLEASE DO NOT HESITATE TO ASK US! Yes No Have you ever had an operation or surgery of any Yes No Eyelid tattoo kind? If so, please list them all with dates. Yes No Penile prosthesis Yes No Shunt Yes No Artificial heart valve Yes No Infusion pump Yes No Pacemaker, wires, or defibrillator Yes No Diabetes Yes No Cochlear implant Yes No Magnetic implant anywhere If you have Diabetes, what medications are Yes No Electrical stimulator for nerves or bone you taking? Yes No Brain aneurysm clip Yes No Are you claustrophobic? Yes No Hypertension Yes No Have you ever been a machinist, welder, or If you have Hypertension, what medications metalworker? are you taking? Yes No Have you ever been hit in the face or eye with a piece of metal (including metal shavings, slivers, The following items may become damaged or cause bullets or BBs? injury to others in a strong magnetic field. THEY Yes No Are you pregnant, possibly pregnant, or breast MUST NOT BE TAKEN INTO THE feeding? SCAN ROOM. Yes No Body piercing Yes No Metal shrapnel or fragments Hearing Aid Purse/pocketbook Yes No Ortho devices (plates/screws/pins /rods/wires) Glasses Pens/pencils -

The Thetford Treasure

The Thetford Treasure A MAJOR FIND OF LATE ROMAN GOLD AND SILVER Catherine Johns The British Museum, London, U.K. At the end of 1979, a group of gold and silver ob- The gold objects are visually the most striking jects dating to the end of the 4th century A.D. was items, and they are all illustrated here. Probably the found buried near Thetford, Norfolk, in eastern most magnificent is the belt-buckie with a bow form- England. Under British law, gold and silver found in ed of two confronted horses' heads and a rectangular the ground must be declared to the authorities, and if plate decorated in relief with a dancing satyr holding the appropriate court of law decides that the unknown aloft a bunch of grapes. The rings, all but one for a original owner buried them for safety, hoping to female rather than a male hand, are in typically late- retrieve them, they are declared to be Treasure Trove antique taste, utilizing coloured settings — amethysts, and the property of the Crown. In the case of objects nicolo, garnets, emeralds and glass — in elaborate and of archaeological importance, this means in practice richly textured mounts. Some of the rings have that they will be acquired by a museum. Though engraved . ornament on the shoulders, while several there were some delays in the case of the Thetford have intricate patterns applied in gold wire and tiny treasure, it was eventually declared Treasure Trove in globules; three have shoulders shaped in the form of February 1981, and, at the time of writing, is under animals, dolphins in two cases and birds in the other. -

METAL ENAMELING Leader Guide Pub

Arts & Communication METAL ENAMELING Leader Guide Pub. No. CIR009 WISCONSIN 4-H PUBLICATION HEAD HEART HANDS HEALTH Contents Before Each Meeting: Checklist ..............................1 Adhesive Agents or Binders ....................................6 Facilities Tools, Materials and Equipment Safety Precautions..................................................6 Resource Materials Kiln Firing and Table-Top Units Expenses Metal Cutting and Cleaning Planning Application of Enamel Colors Youth Leaders Other Cautions Project Meeting: Checklist ......................................3 Metal Art and Jewery Terms ...................................7 Purposes of 4-H Arts and Crafts ...........................................8 Components of Good Metal Enameling Futher Leader Training Sources of Supplies How to Start Working Prepare a Project Plan Bibiography ............................................................8 Evaluation of Projects Kiln Prearation and Maintenance ...........................6 WISCONSIN 4-H Pub. No. CIR009, Pg. Welcome! Be sure all youth are familiar with 4H158, Metal Enameling As a leader in the 4-H Metal Enameling Project, you only Member Guide. The guide suggests some tools (soldering need an interest in young people and metal enameling to be irons and propane torches), materials and methods which are successful. more appropriate for older youth and more suitable for larger facilities (school art room or spacious county center), rather To get started, contact your county University of Wisconsin- than your kitchen or basement. Rearrange these recommen- Extension office for the 4-H leadership booklets 4H350, dations to best suit the ages and abilities of your group’s Getting Started in 4-H Leadership, and 4H500, I’m a 4-H membership and your own comfort level as helper. Project Leader. Now What Do I Do? (also available on the Wisconsin 4-H Web Site at http://www.uwex.edu/ces/4h/ As in any art project, a generous supply of tools and pubs/index.html). -

Guidelines for Uniform June 2019

Guidelines for Uniform Overall responsibility: Executive Committee Updated: June 2019 To be reviewed in: June 2022 June 2019 Page 1 of 4 Guidelines for Uniform General Guidelines • It is important that Leaders portray a good public image, give a good example to the girls and are proud of their uniform. • A mix and match uniform is worn by members of the Irish Girl Guides for all occasions, including Unit meetings. • For girls, the uniform tops are promoted and sold as a package deal i.e. it is necessary for members to have both the inner and outer uniform tops. • For safety reasons, jeans are not allowed for hill walking or hikes. Jewellery should not be excessive. • IGG uniform is sold in IGG Distribution Centres with the IGG logo on it. The logo must not be reproduced on other items of clothing unless prior permission is given by the Chief Executive Officer. In this case, the IGG logo (with writing underneath) in official pantone shades should be used and National Office must have a copy of the final version used. Please refer to the Guidelines for Logo. • Members whose photographs are published in IGG publications must be in correct uniform. If the majority of members in a group photograph are in correct uniform, that photograph can be used to promote IGG in social media and in the Out and About section of Trefoil News. Girl Uniform – Ladybirds. Brownies and Guides • Ladybirds (aged 5-7): Inner top: red polo shirt with a yellow IGG logo Outer top: red sweatshirt with a yellow IGG logo Bottoms: plain navy tracksuit bottoms or skirt -

ITQ-01429- Public Safety Uniforms Commodity Code(S)

Summary Description: ITQ-01429- Public Safety Uniforms Commodity Code(s): 200-44, 70, 85, 800-64 Solicitation Opening/ Closing Date: January 31, 2020 SBD Measures: SBE Preference Prepared by: Latavia Durham/Sherry Clentscale Signature: Date: Verified by: Sherry Clentscale Date: 6/17/20 Signature: Date: Verified by: Basia Pruna Date: 6/18/20 Signature: Date: MONICA MANUFACTURING NIGHT LIGHT GOLD NUGGET DBA IPA CORP DBA ALL UNIFORM DESIGNLAB, INC. GLOBAL TRADING, INC. SAFETY ARGO UNIFORM CO. CORPORATION Vendor Name: WEAR PRODUCTS LLC Submittal FEIN No.→ 59-2601557 56-2051141 65-0300267 59-2015949 65-0295968 81-2229182 19840 Cutler 837 Forward Pass 7190 SW 87th Avenue, Suite 825 Old Airport Rd. Greenville, 7500 NW 25 Street, Unit 12 101 North Dixie Highway Court Cutler Bay, RD SW Pataskala, ADPICS Address→ 207 Miami, FL 33173 SC 29607 Miami, FL 33122 Hallandale Beach, FL 33009 FL 33189 OH 43062 Submittal E-mail→ [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Submittal Telephone→ 786-431-0704 864-297-7199 305-471-4455 954-457-7100 305-255-5431 740-963-2975 Contact Person on ITB→ Allan Baltodano Matt Moller Viraj Wikramanayake Sandy Evans Cristina Cederna Kevin Rider Registered in ADPICS?→ Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Miami-Dade Address→ Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes FL Corp. (SunBiz) Status? → Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Miami-Dade Affidavits Complete & Signed? → Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Collusion Affidavit submitted → Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Compliance Review -

Anglo-Saxon Beast Sculpture Trail Sutton

Supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund Sutton Hoo Anglo-Saxon beast sculpture trail Welcome to Sutton Hoo’s sculpture trail. This trail has been created for us by a group of local sculpture artists, inspired by both beasts depicted on objects discovered at Sutton Hoo and the wider world of Anglo-Saxon design and legend. We hope you enjoy your wander through the woods. Map Use this map to help you find all of the animal sculptures in the woods. 7 6 5 8 4 1 3 2 1. 2. The first sculpture, behind the café, is a large Once you have crossed Garden Field you will boar. This boar is inspired by the crest of the come across a large frog beside the gate into Benty Grange helmet. The Benty Grange helmet the woods. The frog sculpture is inspired by was excavated in Derbyshire in 1848. Little the frog lurking in the design of the gold belt remained of the original helmet bar the frame buckle discovered in Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo. of riveted iron strips and the copper alloy boar The belt buckle is awash with depicitions crest which featured garnet eyes surrounded by of different animals including serpents and gold filigree decoration. Boar-crested helmets dragons. Take a trip to the High Hall exhibition are mentioned in Beowulf no less than five to see a replica of the buckle and an animation times. The boar was a symbol of strength and revealing the location of all the animals in its ferocity; important attributes for any warrior. -

JMD How to Enamel Jewelry

PRESENTS How to Enamel Jewelry: Expert Enameling Tips, Tools, and Techniques Jewelry Making Daily presents How to Enamel Jewelry: Expert Enameling Tips, Tools, and Techniques 7 3 21 ENAMELING TIPS BY HELEN I. DRIGGS 12 10 TORCH FIRED ENAMEL ENAMELING MEDALLION NECKLACE BY HELEN I. DRIGGS BY HELEN I. DRIGGS ENAMELED FILIGREE BEADS BY PAM EAST I LOVE COLOR! In jewelry making, enamel is one of the most In “Enameled Filigree Beads,” Pam East walks you through a versatile sources of pure, luscious color – powdered glass you simple technique of torch firing enamel onto a premade bead can apply with great precision onto silver, gold, copper, and using a handheld butane torch instead of an enameling kiln. other jewelry metals. With enamels, you can paint with a broad The enamel adds color to the bead, while the silver filigree brush or add minute and elaborate detail to pendants, brace- creates the look of delicate cells like those in cloisonné enamel lets, earrings, and more. You can work in rich, saturated tones work. And in “Torch Fired Enamel Medallion Necklace,” Helen or in the subtlest of pastels. You can create a world of sharp Driggs shows you how to create your own torch fired enamel contrast in black and white or one entirely of shades of gray. “cabochons,” how to tab set those cabs, and how to stamp You can even mimic the colors of the finest gemstones, but you and patinate the surrounding metalwork, which you can put can also produce hues and patterns you’d never find among the together using the chain of your choice. -

Raymond & Leigh Danielle Austin

PRODUCT TRENDS, BUSINESS TIPS, NATIONAL TONGUE PIERCING DAY & INSTAGRAM FAVS Metal Mafia PIERCER SPOTLIGHT: RAYMOND & LEIGH DANIELLE AUSTIN of BODY JEWEL WITH 8 LOCATIONS ACROSS OHIO STATE Friday, August 14th is NATIONAL TONGUE PIERCING DAY! #nationaltonguepiercingday #nationalpiercingholidays #metalmafialove 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Semi Precious Stone Disc Internally Threaded Starting At $7.54 - TBRI14-CD Threadless Starting At $9.80 - TTBR14-CD 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Swarovski Gem Disc Internally Threaded Starting At $5.60 - TBRI14-GD Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-GD @fallenangelokc @holepuncher213 Fallen Angel Tattoo & Body Piercing 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Dome Top 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Dome Top 14G ASTM F-67 Titanium Barbell Assortment Internally Threaded Starting At $5.46 - TBRI14-DM Internally Threaded Starting At $5.46 - TBRI14-DM Starting At $17.55 - ATBRE- Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-DM Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-DM 14G Threaded Barbell W Plain Balls 14G Steel Internally Threaded Barbell W Gem Balls Steel External Starting At $0.28 - SBRE14- 24 Piece Assortment Pack $58.00 - ASBRI145/85 Steel Internal Starting At $1.90 - SBRI14- @the.stabbing.russian Titanium Internal Starting At $5.40 - TBRI14- Read Street Tattoo Parlour ANODIZE ANY ASTM F-136 TITANIUM ITEM IN-HOUSE FOR JUST 30¢ EXTRA PER PIECE! Blue (BL) Bronze (BR) Blurple Dark Blue (DB) Dark Purple (DP) Golden (GO) Light Blue (LB) Light Purple (LP) Pink (PK) Purple (PR) Rosey Gold (RG) Yellow(YW) (Blue-Purple) (BP) 2 COPYRIGHT METAL MAFIA 2020 COPYRIGHT METAL MAFIA 2020 3 CONTENTS Septum Clickers 05 AUGUST METAL MAFIA One trend that's not leaving for sure is the septum piercing. -

Camp Charles F. Perry 2016 Summer Camp Leaders Guide

Rio Grande Council Camp Charles F. Perry 2016 Summer Camp Leaders Guide A tradition since 1927 **Updated on 05/20/2016** 1 2016 Summer Camp Leaders Guide Camp Charles F. Perry TABLE OF CONTENTS Map to Camp Perry & Camp Perry Layout ........................................................................................... 3-4 Greetings from the Camp Director ........................................................................................................... 5 Summer Camp Dates & Fees ................................................................................................................... 6 Texas Youth Camps Safety & Health ...................................................................................................... 7 Maverick Scouts - Troop 1927 ................................................................................................................. 8 Welcome from the Program Directors ...................................................................................................... 9 Program Areas....................................................................................................................................... 10 Merit Badge Schedule for Camp Perry .................................................................................................. 11 Daily Schedule for Camp Perry……………………………………………...……………………..……..12 Laguna Station Merit Badge Schedule .................................................................................................. 13 Participant Requirements for