The Thetford Treasure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCJROTC UNIFORM STANDARDS A

GROOMING & UNIFORM STANDARDS Cadets are expected to maintain high standards of appearance and conduct on and off campus. CADETS ARE REQUIRED TO COMPLY with MCJROTC grooming and personal appearance standards as stipulated in NOMMA regulations and Marine Corps Order 1533.6E. Personal appearance and wearing the uniform is a significant part of a cadet's MCJROTC grade. The grooming regulations apply to military, NOMMA and civilian attire when worn in conjunction with Academy functions. Grooming and personal appearance standards are required to be followed daily and at all NOMMA events (i.e. graduation, prom, dances, sporting events, summer camps and extracurricular activities). Cadets who refuse or repeatedly fail to adhere to the prescribed grooming and personal appearance standards will receive disciplinary action according to NOMMA discipline policy. 1. Common Standards: All haircuts/hairstyles, for both male and female cadets will be checked every day, during inspection, and will contribute toward exam grades. a. Haircuts and hair styles are not permitted to be faddish or eccentric. Mohawks, derivations of Mohawks and cuts or styles with shaved or designed portions of the scalp are not permitted. Braids and/or derivations of braids, including locks and twists, may be permitted for females only if hair is firmly secured according to the LONG HAIR regulations noted below (and per MARADMIN 622/15). b. No designs are allowed to the hair; only one straight part in the hair is authorized. c. Hair must be a natural color (blonde, brown, black) and be consistent over the entire head (no multi-colored braids or spots). d. Shaving/slashing of eyebrows is NOT authorized. -

Mark Standifer's Electrical Safety Briefing

E3948 Mark Standifer’s Electrical Safety Briefing Leader’s Guide © ERI Safety Videos MARK STANDIFER’S ELECTRICAL SAFETY BRIEFING This easy-to-use Leader’s Guide is provided to assist in conducting a successful presentation. Featured are: INTRODUCTION: A brief description of the program and the subject that it addresses. PROGRAM OUTLINE: Summarizes the program content. If the program outline is discussed before the video is presented, the entire program will be more meaningful and successful. PREPARING FOR AND CONDUCTING THE PRESENTATION: These sections will help you set up the training environment, help you relate the program to site-specific incidents, and provide program objectives for focusing your presentation. REVIEW QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS: Questions may be copied and given to participants to document how well they understood the information that was presented. Answers to the review questions are provided separately. INTRODUCTION With nearly 40 years of experience as an electrician, Mark Standifer delivers powerful seminars on the shock and burn hazards associated with electrical work. As a survivor of an arc flash incident, Mark knows the pain and suffering associated with electrical and arc flash injuries. In this live presentation, he stresses the importance of thinking about what we are doing and being aware of all shock and burn hazards when performing electrical job tasks. Mark also makes the point that we must always wear the PPE and FR rated clothing required by the NFPA 70E to protect ourselves from any mistakes that we may make. Viewers will also learn unforgettable lessons about electrical safety from stories about Mark’s incident and his friend’s electrocution. -

Mri Exam Questionnaire to Our Patients and Accompaning Family Members

EL PORTAL IMAGING CENTER Weight: Height: MRI EXAM QUESTIONNAIRE TO OUR PATIENTS AND ACCOMPANING FAMILY MEMBERS... The MR room contains a very strong magnet. Before you are allowed to enter, we must know if you have any metal in your body. Some metal objects can interfere with your scan or may even be dangerous, so PLEASE answer the following questions carefully. If you have a question regarding anything on this form, PLEASE DO NOT HESITATE TO ASK US! Yes No Have you ever had an operation or surgery of any Yes No Eyelid tattoo kind? If so, please list them all with dates. Yes No Penile prosthesis Yes No Shunt Yes No Artificial heart valve Yes No Infusion pump Yes No Pacemaker, wires, or defibrillator Yes No Diabetes Yes No Cochlear implant Yes No Magnetic implant anywhere If you have Diabetes, what medications are Yes No Electrical stimulator for nerves or bone you taking? Yes No Brain aneurysm clip Yes No Are you claustrophobic? Yes No Hypertension Yes No Have you ever been a machinist, welder, or If you have Hypertension, what medications metalworker? are you taking? Yes No Have you ever been hit in the face or eye with a piece of metal (including metal shavings, slivers, The following items may become damaged or cause bullets or BBs? injury to others in a strong magnetic field. THEY Yes No Are you pregnant, possibly pregnant, or breast MUST NOT BE TAKEN INTO THE feeding? SCAN ROOM. Yes No Body piercing Yes No Metal shrapnel or fragments Hearing Aid Purse/pocketbook Yes No Ortho devices (plates/screws/pins /rods/wires) Glasses Pens/pencils -

ITQ-01429- Public Safety Uniforms Commodity Code(S)

Summary Description: ITQ-01429- Public Safety Uniforms Commodity Code(s): 200-44, 70, 85, 800-64 Solicitation Opening/ Closing Date: January 31, 2020 SBD Measures: SBE Preference Prepared by: Latavia Durham/Sherry Clentscale Signature: Date: Verified by: Sherry Clentscale Date: 6/17/20 Signature: Date: Verified by: Basia Pruna Date: 6/18/20 Signature: Date: MONICA MANUFACTURING NIGHT LIGHT GOLD NUGGET DBA IPA CORP DBA ALL UNIFORM DESIGNLAB, INC. GLOBAL TRADING, INC. SAFETY ARGO UNIFORM CO. CORPORATION Vendor Name: WEAR PRODUCTS LLC Submittal FEIN No.→ 59-2601557 56-2051141 65-0300267 59-2015949 65-0295968 81-2229182 19840 Cutler 837 Forward Pass 7190 SW 87th Avenue, Suite 825 Old Airport Rd. Greenville, 7500 NW 25 Street, Unit 12 101 North Dixie Highway Court Cutler Bay, RD SW Pataskala, ADPICS Address→ 207 Miami, FL 33173 SC 29607 Miami, FL 33122 Hallandale Beach, FL 33009 FL 33189 OH 43062 Submittal E-mail→ [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Submittal Telephone→ 786-431-0704 864-297-7199 305-471-4455 954-457-7100 305-255-5431 740-963-2975 Contact Person on ITB→ Allan Baltodano Matt Moller Viraj Wikramanayake Sandy Evans Cristina Cederna Kevin Rider Registered in ADPICS?→ Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Miami-Dade Address→ Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes FL Corp. (SunBiz) Status? → Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Miami-Dade Affidavits Complete & Signed? → Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Collusion Affidavit submitted → Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Compliance Review -

Anglo-Saxon Beast Sculpture Trail Sutton

Supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund Sutton Hoo Anglo-Saxon beast sculpture trail Welcome to Sutton Hoo’s sculpture trail. This trail has been created for us by a group of local sculpture artists, inspired by both beasts depicted on objects discovered at Sutton Hoo and the wider world of Anglo-Saxon design and legend. We hope you enjoy your wander through the woods. Map Use this map to help you find all of the animal sculptures in the woods. 7 6 5 8 4 1 3 2 1. 2. The first sculpture, behind the café, is a large Once you have crossed Garden Field you will boar. This boar is inspired by the crest of the come across a large frog beside the gate into Benty Grange helmet. The Benty Grange helmet the woods. The frog sculpture is inspired by was excavated in Derbyshire in 1848. Little the frog lurking in the design of the gold belt remained of the original helmet bar the frame buckle discovered in Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo. of riveted iron strips and the copper alloy boar The belt buckle is awash with depicitions crest which featured garnet eyes surrounded by of different animals including serpents and gold filigree decoration. Boar-crested helmets dragons. Take a trip to the High Hall exhibition are mentioned in Beowulf no less than five to see a replica of the buckle and an animation times. The boar was a symbol of strength and revealing the location of all the animals in its ferocity; important attributes for any warrior. -

30.3 Gail & Yazzie.Cb5.Fin

30.3_GAIL & YAZZIE.CB5.FIN 3/21/07 2:38 PM Page 42 GAIL BIRD uses gr aph pa per to design, plan and arrange pearls for a necklace of Akoyo pearls from Japan. During this pr ocess, she selects stones f or individual settings, or satellites, as well as for clasps. Next, she draws the necklace on graph paper. On her desk sits the pear l necklace, graph paper, notebooks of drawings, two boxes of colored pencils, and a container of colored pencils , a triangle for measuring and dr awing str aight lines , raw stones , the finished drawing, and a tr ay with stones f or earr ings. Caption courtesy of Shared Images: The Innovative Jewelry of Yazzie Johnson & Gail Bir d, published by the Hear d Museum and Museum of New Mexico Press. YAZZIE JOHNSON pulls sixteen-g auge silv er or gold wire thr ough a dr awplate to m ake it thinner and stronger for use as earr ing loops or to twist and appliqué as a surf ace decor ation. The dr awplate allows Johnson to buy one g auge (or thic kness) of wire and pull it to m ake different gauges for various needs. Johnson begins b y filing the wire to a point and positions it in the dr awplate. He uses his f eet as leverage and pulls the wire se veral times thr ough successively smaller-diameter holes to achie ve the desired size. Caption courtesy of Shared Images: The Innovative Je welry of Yazzie Johnson & Gail Bir d, published b y the Hear d Museum and Museum of New Mexico Press. -

Fin 06 Julyfs

DRAFT Budget to Actual Summary By Department For the month of July 2021 Dept. Dept. Budgeted Actual Budgeted Actual Net Income/ Fund Code Name Revenue Revenue Expense Expense (Loss) 01 90 Admin 880,376 428,020 743,371 737,006 (308,986) 01 30 Sust. - - 5,609 4,520 (4,520) 01 40 Police 423,731 415,527 644,500 560,542 (145,015) 01 50 B&H 114,519 112,187 49,554 60,254 51,933 01 70 IT - - 33,655 22,795 (22,795) 01 80 PW 11,667 5,742 346,439 324,041 (318,299) 05 05 Fire 101,597 101,557 25,043 29,315 72,242 07 07 Rec 18,919 2,670 19,631 19,070 (16,400) 08 08 WW 543,192 684,142 382,467 296,674 387,468 09 09 Parking 338,042 432,187 248,253 129,761 302,426 10 10 Capital - - 3,138 - - 15 15 Liquid Fuels 83 51 33,690 785 (734) 16 16 SPF 6,042 29,804 235,371 32,727 (2,923) 18 18 Cap. Resv - - - - - 19 19 Equip. - - 10,942 10,942 (10,942) Total 2,438,167 2,211,887 2,781,663 2,228,431 (16,544) PAGE 1 DRAFT Budget to Actual Summary By Department For the Year Ended July 31, 2021 Dept. Dept. Original Actual % of Budget Original Actual % of Budget Net Income/ Fund Code Name Budget Revenue Remaining Budget Expense Remaining (Loss) 01 90 Admin 15,739,839 11,625,725 26% 5,000,664 2,774,093 45% 8,851,632 01 30 Sust. -

B&MRRHS Display Case Collection 2021

Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Incorporated Assortment of railroad artifacts have now been preserved in display cases purchased by the society in 2018 16.5”x 12.5” Display cases Boston & Maine Railroad China Place Setting Feb 21, 1932 Menu B&MRR Snow Train Anonymous Donor Boston & Maine Railroad Assortment Conductor & Trainman Badges B&M Railroad Police Patch B&M Baggage Checks B&M Pins & Uniform Buttons Fitchburg Conductor & Brakeman Hat Badges. B&M Lighter, Ticket Puncher. Anonymous Donor Boston & Maine Railroad Brass Conductor Badges Brass Uniform Pins From the collection of former B&MRR Conductor Arthur E. Paquette Donation by; Mr. David C. Paquette Boston & Maine Railroad Silver Trainman Badges Silver Trainman Uniform Pins and Belt Buckles From the collection of former B&MRR Trainman Arthur E. Paquette Donation by; Mr. David C. Paquette Boston & Maine Railroad Assortment B&M Belt Buckles B&M Uniform Buttons B&M Brass Conductor Hat Badge PRR Belt Buckle, A.E.P. Belt Buckle United Transportation Works Union Lapel Pins. Donation by; Mr. David C. Paquette Boston & Maine Railroad Police Badges President Police Badge 2 Officers Police Badges 11 Police Badges Donation by; Mr. Alan Dustin Boston & Maine Railroad Station Agent – Telegrapher 25 & 50 Years Award Pins Photo Lowell B&M Station Photo Mr. Stanley E. Champeau Railroad Pass Cards 1928 New York Central Railroad 1927 Central Railroad Co. of New Jersey 1957 Boston & Maine Railroad No. 12902 1957 Boston & Maine Railroad No. 27419 Donation by; Ms. Belinda Champeau Boston & Maine Railroad Award Letter Mr. Stanley E. Champeau 50 Years of Service North Station, Boston, Mass Feb 29, 1968 Donation by; Ms. -

Exhibit Catalog (PDF)

Mastery in Jewelry & Metals: Irresistible Offerings! Gail M. Brown, Curator Mastery in Jewelry & Metals: Irresistible Offerings! Gail M. Brown, Curator Participating Artists Julia Barello Mary Lee Hu Harriete Estel Berman Michael Jerry Elizabeth Brim Robin Kranitzky & Kim Overstreet Doug Bucci Rebecca Laskin Kathy Buszkiewicz Keith Lewis Harlan W. Butt Charles Lewton-Brain Chunghi Choo Linda MacNeil Sharon Church John Marshall John Cogswell Bruce Metcalf Chris Darway Eleanor Moty Jack DaSilva Tom Muir Marilyn DaSilva Harold O'Connor Robert Ebendorf Komelia Okim Sandra Enterline Albert Paley Fred Fenster Beverly Penn Arline Fisch Suzan Rezac Pat Flynn Stephen Saracino David C. Freda Hiroko Sato-Pijanowski Don Friedlich Sondra Sherman John G. Garrett Helen Shirk Lisa Gralnick Lin Stanionis Gary S. Griffin Billie Theide Laurie Hall Rachelle Thiewes Susan H. Hamlet Linda Threadgill Douglas Harling What IS Mastery? A singular idea, a function, a symbol becomes a concept, a series, a marker- a recognizable visual attitude and identifiable vocabulary which grows into an observation, a continuum, an unforgettable commentary. Risk taking. Alone and juxtaposed….so many ideas inviting exploration. Contrasting moods and attitudes, stimuli and emotional temperatures. Subtle or bold. Serene or exuberant. Pithy observations of the natural and WHAT is Mastery? manmade worlds. The languages of beauty, aesthetics and art. Observation and commentary. Values and conscience. Excess and dearth, The pursuit and attainment, achievement of purpose, knowledge, appreciation and awareness. Heavy moods and childlike insouciance. sustained accomplishment and excellence. The creation of irrepressible, Wisdom and wit. Humor and critique. Reality and fantasy. Figuration important studio jewelry and significant metal work: unique, expressive, and abstraction. -

His Exhibition Features More Than Two Hundred Pieces of Jewelry Created Between 1880 and Around 1930. During This Vibrant Period

his exhibition features more than two hundred pieces of jewelry created between 1880 and around 1930. During this vibrant period, jewelry makers in the world’s centers of design created audacious new styles in response to growing industrialization and the changing Trole of women in society. Their “alternative” designs—boldly artistic, exquisitely detailed, hand wrought, and inspired by nature—became known as art jewelry. Maker & Muse explores five different regions of art jewelry design and fabrication: • Arts and Crafts in Britain • Art Nouveau in France • Jugendstil and Wiener Werkstätte in Germany and Austria • Louis Comfort Tiffany in New York • American Arts and Crafts in Chicago Examples by both men and women are displayed together to highlight commonalities while illustrating each maker’s distinctive approach. In regions where few women were present in the workshop, they remained unquestionably present in the mind of the designer. For not only were these pieces intended to accent the fashionable clothing and natural beauty of the wearer, women were also often represented within the work itself. Drawn from the extensive jewelry holdings of collector Richard H. Driehaus and other prominent public and private collections, this exhibition celebrates the beauty, craftsmanship and innovation of art jewelry. WHAT’S IN A LABEL? As you walk through the exhibition Maker and Muse: Women and Early Guest Labels were written by: Twentieth Century Art Jewelry you’ll Caito Amorose notice a number of blue labels hanging Jon Anderson from the cases. We’ve supplemented Jennifer Baron our typical museum labels for this Keith Belles exhibition by adding labels written by Nisha Blackwell local makers, social historians, and Melissa Frost fashion experts. -

Maker-Muse-Addendum-A.Pdf

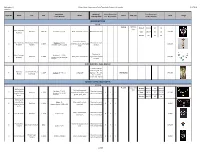

Addendum A Maker Muse: Women and Early Twentieth Century Art Jewelry 5/1/2018 Checklist Dimensions Mounting/ Mount Dimensions Case Dimensions Object No. Maker Title Date Media Case # Case Type Value Image H x W x D inches Installing Notes H x W x D inches H x W x D inches INTRODUCTION FC 1/6 FlatTable FC 1/6 Overall 50 1/4 36 20 Case Mrs. Charlotte 1 Pendant 1884-90 2 3/8 x 1 1/2 x 1/4 Gold, amethyst, enamel Mounted into deck - - - Case 38 1/4 36 20 $10,000 Newman Vitrine 12 36 12 Carved moonstone, Mrs. Charlotte Mary Queen of Scots Necklace: 20 1/2 Mounted on riser 2 c. 1890 amethyst, pearl, yellow gold - - - $16,500 Newman Pendant Pendant: 2 3/4 x 1 1/16 on deck chain Displayed in Mrs. Charlotte Necklace: L: 15 3/8 3 Necklace c. 1890 Gold, pearl, aquamarine original box directly - - - $19,000 Newman Pendant: 2 5/8 x 3 15/16 on deck INTRODUCTION - WALL DISPLAY Framed, D-Rings; wall hang; 68 - 72 Alphonse Sarah Bernhardt as 4 c. 1894 Framed: 96 x 41 x 2 Lithograph degrees F, 45 - 55% - - - Wall display $40,000 Mucha Gismonda RH, 5 - 7 foot candles (50 - 70 lux) BRITISH ARTS AND CRAFTS TC 1/10 TC 1/10 Large table Attributed to Overall 83 3/4 42 26 1/2 Gold, white enamel, case Jessie Marion Necklace: 5 11/16 Mounted on oval 5 Necklace c. 1905 chrysoberyl, peridot, green 8 6 1 Table 38 1/4 42 26 1/2 $11,000 King for Liberty Pendant: 2 x 13/16 riser on back deck garnet, pearl, opal & Co. -

Fusing Fusing

® Artist Robert Wiener FusingFusing ToolsTools && AccessoriesAccessories ProductProduct CatalogCatalog www.dlartglass.com © 2019 D&L Art Glass Supply © 2019 D&L Art Glass Artist Nancy Bonig 303.449.8737 • 800.525.0940 Table of Contents About the Artwork Cover - Artist: Robert Wiener, DC Art Glass Series: Colorbar Murrine Series Title: Summer Salsa Size: 6" square (approx.) Website: www.dcartglass.com Photographer: Pete Duvall Table of Contents- Alice Benvie Gebhart Title: Distant Fog Size: 6 x 8" Website: www.alicegebhart.com Kilns ..........................................................................1-16 Tabletop Kilns .......................................................................................................... 1–3 120 Volt Kilns ............................................................................................................1-5 240 Volt Kilns ........................................................................................................ 6-12 Kiln Controllers at a Glance .....................................................................................13 Kiln Shelves .......................................................................................................... 14–15 Kiln Furniture and Accessories ................................................................................16 Kiln Working Supplies ....................................... 17-20 Primers & Shelf Paper ...............................................................................................17 Fiber Products & Release