V6 BIM Chapman-Andrews.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MW Bocasjudge'stalk Link

1 Bocas Judge’s talk To be given May 4 2019 Marina Warner April 27 2019 The Bocas de Dragon the Mouths of the Dragon, which give this marvellous festival its name evoke for me the primary material of stories, songs, poems in the imagination of things which isn’t available to our physical senses – the beings and creatures – like mermaids, like dragons – which every culture has created and questioned and enjoyed – thrilled to and wondered at. But the word Bocas also calls to our minds the organ through which all the things made by human voices rise from the inner landscapes of our being - by which we survive, breathe, eat, and kiss. Boca in Latin would be os, which also means bone- as Derek Walcott remembers and plays on as he anatomises the word O-mer-os in his poem of that name. Perhaps the double meaning crystallises how, in so many myths and tales, musical instruments - flutes and pipes and lyres - originate from a bone, pierced or strung to play. Nola Hopkinson in the story she read for the Daughters of Africa launch imagined casting a spell with a pipe made from the bone of a black cat. When a bone-mouth begins to give voice – it often tells a story of where it came from and whose body it once belonged to: in a Scottish ballad, to a sister murdered by a sister, her rival for a boy. Bone-mouths speak of knowledge and experience, suffering and love, as do all the writers taking part in this festival and on this splendid short list. -

Special Issue November/December 2015 Founding Editors Richard Georges David Knight Jr

Special Issue November/December 2015 Founding Editors Richard Georges David Knight Jr. Consulting Editors Carla Acevedo-Yates Traci O’Dea Freeman Rogers Guest Editors Ayanna Gillian Lloyd Marsha Pearce Colin Robinson Art Direction Clayton Rhule Moko is a non-profit journal that publishes fiction, poetry, visual arts, and non-fiction essays that reflect a Caribbean heritage or experience. Our goal is to create networks with a Pan-Caribbean ethos in a way that is also sensitive to our location within the British and United States Virgin Islands. We embrace diversity of experience and self-expression. Moko seeks submissions from both established and emerging writers, artists, and scholars. We are interested in work that encourages questioning of our societies and ourselves. We encourage you to submit your best work to us whether it be new visual art, fiction, poetry, reviews, interviews, or essays on any topic relevant to the Caribbean experience. We publish in March, July, and November. www.mokomagazine.org Moko November 2015 Number 7 Moko (ISSN: 2333-2557) is published three times a year. Address correspondence to PO Box 25479, EIS 5113, Miami, Florida 33102-5479. Copyright © 2015 Moko. All rights reserved. All works published or displayed by Moko are owned by their respective authors. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, in creative works contained herein is entirely coincidental. 2 MOKO | CARIBBEAN ART LETTERS FIRING THE CANON TABLE OF CONTENTS Firing the Canon Guest Editorial 5 VISUAL ART Arriving in the Art World Marsha Pearce 7 Featured Artist Nominator Harley Davelaar Tirzo Martha 11 Versia Harris Annalee Davis 17 Alex David Kelly Richard Mark Rawlins 21 Kelley-Ann Lindo Deborah Anzinger 27 Jean-Claude Saintilus André Eugène 31 Lionel Villahermosa Loretta Collins Klobah 39 FICTION Holding Space Ayanna Gillian Lloyd 51 Featured Author Nominator Alake Pilgrim Monique Roffey 55 Anna Levi Monique Roffey 61 Brenda Lee Browne Joanne C. -

Linton Kwesi Johnson Artist-In-Residence | Fall 2014 Institute of African American Affairs New York University Linton Kwesi Johnson Fall 2014 Artist-In-Residence

Institute of African American Affairs presents PHOTO © DANNY DA COSTA Linton Kwesi Johnson Artist-in-Residence | Fall 2014 Institute of African American Affairs New York University Linton Kwesi Johnson Fall 2014 Artist-in-Residence THE PROGRAMS FRIDAY, SEPT 19, 2014 / 7:30 PM Linton Kwesi Johnson main lecture: “African Consciousness in Reggae Music” Growing up in London, reggae music provided Johnson with not only a sense of identity but also a career as a successful recording artist and performer. Kimmel Center – NYU • Rosenthal Pavilion • 10th Floor PHOTO © DANNY DA COSTA DA © DANNY PHOTO 60 Washington Square South • New York, NY THE ARTIST TUESDAY, SEPT 23, 2014 / 7:00 PM Linton Kwesi Johnson is a Jamaican-born British national An Evening of Poetry whose work focuses on African Caribbean cultural expressions in poetry and reggae music, from both sides of the Atlantic during with Linton Kwesi Johnson a career spanning over four decades. The program of events for Johnson’s brief tenure at NYU–IAAA will include examining these followed by discussion chaired by British Caribbean novelist and fields of artistic creativity. Johnson will also take the opportunity essayist, Caryl Phillips, Professor of English at Yale University. to draw on the expertise of some eminent friends in the academy Kimmel Center – NYU • E&L Auditorium • 4th Floor with the aim of engaging students and members of the public in 60 Washington Square South • New York, NY the discussions. Johnson was born in Chapleton, in the parish of Clarendon, Jamaica. After moving to London at an early age and later attending the University of London’s Goldsmiths College, he FRIDAY, SEPT 26, 2014 / 6:00 PM began writing politically charged poetry. -

Vol 23 / No. 1 & 2 / April/November 2015

1 Vol 23 / No. 1 & 2 / April/November 2015 Volume 23 Nos. 1 & 2 April/November 2015 Published by the discipline of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Nadia Huggins Anu Lakhan (copy editor) Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] OR Ms. Angela Trotman Department of Language, Linguistics and Literature Faculty of Humanities, UWI Cave Hill Campus P.O. Box 64, Bridgetown, BARBADOS, W.I. e-mail: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATE US$20 per annum (two issues) or US$10 per issue Copyright © 2015 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Lisa Outar Ian Strachan BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. Edited by full time academics and with minimal funding or institutional support, the Journal originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. -

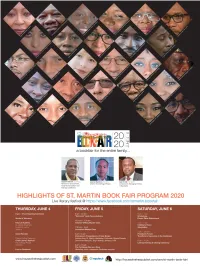

St. Martin Book Fair Program June 4 – 6, 2020

Poster pics of guest authors on the PROGRAM cover | St. Martin Book Fair 2020 L-R, Row 1: Verene Shepherd (Jamaica), Dannabang Kuwabong (Ghanaian/Canadian), Nicole Erna Mae Francis Cotton (St. Martin), Yvonne Weekes (Montserrat/Barbados), Nicole Cage (Martinique), Vladimir Lucien (St. Lucia); Row 2: Ashanti Dinah Orozco Herrera (Colombia), Karen Lord (Barbados), Jean Antoine-Dunne (Trinidad and Tobago/Ireland), Fola Gadet (Guadeloupe), A-dZiko Simba Gegele (Jamaica); Row 3: Richard Georges (Virgin Islands), Sean Taegar (Belize), Jeannine Hall Gailey (USA), Rafael Nino Féliz (Dominican Republic), Stéphanie Melyon-Reinette (Guadeloupe), Fabian Adekunle Badejo (St. Martin); Row 4: Sonia Williams (Barbados), Adrian Fraser (St. Vincent and the Grenadines), Steen Andersen (Denmark), Max Rippon (Marie-Galante, Sirissa Rawlins Sabourin (St. Kitts and Nevis); Row 5: Patricia Turnbull (Virgin Islands), Doris Dumabin (Guadeloupe), René E. Baly (St. Martin/USA), Lili Forbes (St. Martin/USA), Antonio Carmona Báez (Puerto Rico/St. Martin). *** Guest speakers/presenters, L-R: Cozier Frederick (Dominica), Minister for Environment, Rural Modernisation and Kalinago Upliftment; Lorenzo Sanford (Dominica), Chief of the Kalinago People (Dominica); Jean Arnell (St. Martin), Managing Partner and IT Specialist Computech. Click link to see all program activities: www.facebook.com/stmartin.bookfair Purpose and Objectives of the St. Martin Book Fair VISION To be the dynamic platform for books and information on and about St. Martin; establishing an eventful meeting place for the national literature of St. Martin and the literary cultures of the Caribbean; networking with literary cultures from around the world. MISSION STATEMENT To develop a marketplace for the multifaceted and multimedia exhibition and promotion of books, periodicals and publishing technologies and to facilitate St. -

A Review of the Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey.Anthurium , 17(1): 7, 1–4

Glassie, A 2021 Catch and Release: A Review of The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey. Anthurium, 17(1): 7, 1–4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33596/anth.448 REVIEW Catch and Release: A Review of the Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey Alison Glassie University of Virginia, US [email protected] Review of Monique Roffey,The Mermaid of Black Conch: A Love Story. Peepal Tree Press, 2020. 188 pages. Keywords: Monique Roffey; ocean; mermaids; queer; love story In Monique Roffey’s latest novel, the Costa Award-winning The Mermaid of Black Conch: A Love Story, a thousand-year old Taino mermaid named Aycayia resurfaces to indict the logics of possession and extraction that have shaped the Caribbean since colonial contact. Having swum afoul of a sportfishing derby off the rural island of Black Conch in 1976, Aycayia is hooked—quite literally—by “white men from Florida [who] came to fish for marlin and instead pulled a mermaid out of the sea” (7). The ensuing novel, which follows its eponymous mermaid’s rescue and slow, temporary transformation from “barnacled, seaweed-clotted mer- maid” to womanhood, explores Aycayia’s awakening sexuality and foregrounds the transgressive—perhaps even queer—nature of love itself (7). Subtitled “a love story”, The Mermaid of Black Conch is actually a story about love. This distinction is less semantic than it might initially seem. As the novel juxtaposes relation- ships founded upon power, possession and extraction with the genuine loves and frustrations—erotic and otherwise—of the characters who participate in Aycayia’s rescue and wonder aloud about the curse that binds her to the sea, it suggests, following Angelique Nixon and Antonio Benitez-Rojo, that in queerness of gender, sexuality, and literary form, one finds a Caribbeanness as fluid and expansive as the sea itself.1 The author of six novels, four of which are set in Trinidad and the Caribbean, Roffey is a Senior Lecturer on the MA/MFA in Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University, and a tutor at the Norwich Writers Centre. -

P E E P a L T R E E P R E

P E E P A L T R E E P R E S S 2017 Welcome to our 2017 catalogue! Peepal Tree brings you the very best of international writing from the Caribbean, its diasporas and the UK. Founded in 1985, Peepal Tree has published over 370 books and has grown to become the world’s leading publisher of Caribbean and Black British Writing. Our goal is to publish books that make a difference, and though we always want to achieve the best possible sales, we’re most concerned with whether a book will still be alive and have value in the future. Visit us at www.peepaltreepress.com to discover more. Peepal Tree Press 17 Kings Avenue, Leeds LS6 1QS, United Kingdom +44 (0)1 1 3 2451703 contact @ peepaltreepress.com www.peepaltreepress.com Trade Distribution – see back cover Madwoman SHARA MCCALLUM “These wonderful poems open a world of sensation and memory. But it is a world revealed by language, never just controlled. The voice that guides the action here is openhearted and openminded—a lyric presence that never deserts the subject or the reader. Syntax, craft and cadence add to the gathering music from poem to poem with—to use a beautiful phrase from the book, ‘each note tethering sound to meaning.’” —Eavan Boland Sometimes haunting and elusive, but ultimately transformative, the poems in Shara McCallum’s latest collection Madwoman chart and intertwine three stages of a woman’s life from childhood to adulthood to motherhood. Rich with the 9781845233396 / 80 pages / £8.99 POETRY complexities that join these states of being, the poems wrestle with the idea of JANUARY 2017 being girl, woman and mother all at once. -

BIM: Arts for the 21St Century

CELEBRATING LAMMING... BIM: Arts for the 21st Century Patron and Consultant Editor George Lamming Editors Curwen Best Esther Phillips Managing Editor Gladstone Yearwood Editorial Board DeCarla Applewhaite Hilary Beckles Curwen Best Marcia Burrowes Mark McWatt Trevor Marshall Esther Phillips Andy Taitt Board of Management Hilary Beckles Janet Caroo Gale Hall Sheron Johnson Celia Toppin Maurice Webster Gladstone Yearwood International Advisory Board Heather Russell-Andrade / USA Kamau Brathwaite, Barbados / USA Stewart Brown, U.K. Austin Clarke, Barbados/Canada Carolyn Cooper, Jamaica Kwame Dawes, Guyana / USA Margaret Gill, Barbados Lorna Goodison, Jamaica Lennox Honeychurch, Dominica Anthony Kellman, USA/Barbados Sandra Pouchet-Paquet, USA Design Leaf Design Inc. Cover Concept Paul Gibbs, Educational Media Services, The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Publishing Services Legin Holdings Inc. BIM: Arts for the 21st Century Errol Barrow Centre for Creative Imagination, he University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, P. O. Box 64, Bridgetown BB11000, Barbados Telephone: (246) 417-4776 Fax: (246) 417-8903 BIM: Arts for the 21st Century is edited collaboratively by persons drawn from the literary community, who represent the creative, academic and developmental interests critical for the sustainability of the best Caribbean literature. BIM: Arts for the 21st Century is published by the Errol Barrow Centre for Creative Imagination, The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, in collaboration with the Office of the Prime Minister, Government of Barbados. All material copyright by the authors and/or the University of the West Indies. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in BIM: Arts for the 21st Century are the responsibility of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, Errol Barrow Centre for Creative Imagination, The University of the West Indies or the Office of the Prime Minister, Government of Barbados. -

Including 2016 Titles Visit Us at To

Welcome to our Spring/Summer 2017 catalogue! Including 2016 titles Peepal Tree brings you the very best of international writing from the Caribbean, its diasporas and the UK. Founded in 1985, Peepal Tree has published over 350 books and has grown to become the world’s leading publisher of Caribbean and Black British Writing. Our goal is to publish books that make a difference, and though we always want to achieve the best possible sales, we’re most concerned with whether a book will still be alive and have value in the future. Visit us at www.peepaltreepress.com to discover more. Peepal Tree Press 17 Kings Avenue, Leeds LS6 1QS, United Kingdom +44 (0)1 1 3 2451703 info @ peepaltreepress.com www.peepaltreepress.com 1 Madwoman SHARA MCCALLUM “These wonderful poems open a world of sensation and memory. But it is a world revealed by language, never just controlled. The voice that guides the action here is openhearted and openminded—a lyric presence that never deserts the subject or the reader. Syntax, craft and cadence add to the gathering music from poem to poem with—to use a beautiful phrase from the book, ‘each note tethering sound to meaning.’” —Eavan Boland Sometimes haunting and elusive, but ultimately transformative, the poems in Shara McCallum’s latest collection Madwoman chart and intertwine three stages of a woman’s life from childhood to adulthood to motherhood. Rich with the 9781845233396 / 72 pages / £8.99 POETRY complexities that join these states of being, the poems wrestle with the idea of Print / 23 JAN 2017 being girl, woman and mother all at once. -

The Diplomatic Courier Vol

Diplomatic Courier Vol. 1 | Issue 2 | August 7, 2016 The Diplomatic Courier Vol. 1 | Issue 2 | August 7, 2016 [email protected] Plan of Action for People of African Descent launched by OAS and PAHO he Pan American Health Organ- ization (PAHO) announced on TJuly 28 in Washington that it has collaborated with the Organization of American States (OAS) to launch a new Plan of Action for the Americas, including the Caribbean, for Imple- mentation of the International Decade for People of African Descent. PAHO says the initiative seeks to strengthen public policies to protect the rights of this population in the re- gion, “and ensure their full and equal participation between now and 2025.” The initiative also aims to improve the health and well-being of the more than 150 million peo- racial groups due to the inequality, poverty, and social exclu- ple of African descent estimated to live in the Western Hemi- sion they endure, which are closely related to racism, xeno- sphere. phobia and intolerance,” PAHO said. “These populations have worse health outcomes than other Continued on Page 3 Centre established to study the Legacies of British Slave Ownership he Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British the fruits of slavery were transmitted to metropolitan Britain. Slave-ownership has been established at UCL with Those behind the centre believe that research and analy- Tthe generous support of the Hutchins Center at sis of this group are both key to understanding the extent Harvard. and limits of slavery's role in shaping British history and The Centre will build on two earlier projects based at leaving lasting legacies that reach into the present. -

Recitals Book Parties General Sessions Book Fair Workshops

A book fair for the entire family … RECITALS BOOK PARTIES GENERAL SESSIONS BOOK FAIR WORKSHOPS In tribute to Kamau Brathwaite (85th birthday celebration), and Sen. Edward Brooke (1919-2015) A book fair for the entire family … CONTENTS Purpose and Objectives 04 VISION | MISSION STATEMENT | OBJECTIVES Messages 05 SHUJAH REIPH | JACQUELINE SAMPLE DR. FRANCIO GUADELOUPE | HON. ALINE HANSON HON. MARCEL GUMBS Pre-Book Fair Activities 10 JUNE 2 - 3, 2015 Book Fair Program 11 JUNE 4 - 6, 2015 18 AUTHORS AND WORKSHOP PRESENTERS The 13th Annual St. Martin Book Fair Organized by Conscious Lyrics Foundation and House of Nehesi Publishers in collaboration with St. Maarten Tourist Bureau, University of St. Martin LCF Foundation, St. Martin Tourist Office, and sponsors SOS radio, BK Martin Book Fund, SXM Airport. WELCOME | 13TH ANNUAL ST.MARTIN BOOK FAIR Purpose and Objectives of the St. Martin Book Fair VISION OBJECTIVES To be the dynamic platform for books and infor- • To support the right of the people of St. Martin to mation on and about St. Martin; establishing an have full access to books, which are culturally and eventful meeting place for the national literature of materially relevant to their reading needs. St. Martin and the literary cultures of the Caribbean; • To support the right to freedom of expression networking with literary cultures from around the and the fullest possible exchange of ideas and world. information through books and other reading and knowledge-based materials. MISSION STATEMENT • To promote professional ethics and conduct and fair practice in St. Martin and Caribbean book and To develop a marketplace for the multifaceted related industries. -

"Projective Verse," Charles Olson

Projective Verse as a Mode of Socio-Linguistic Protest ANTHONY KELLMAN Form is never more than an extension of content. - CHARLES OLSON IN AN ESSAY entitled "Projective Verse," Charles Olson, the post-modern American poet, describes projective verse as "com• position by field" (148), as "open" poetry, which accommodates a form of imaginative ploughing that is in opposition to the in• herited traditional lines, stanzas, and metres. As such, projective verse becomes a linguistic protest against poetic convention, against established modes of poetic form and expression; and, if one accepts Olson's observation that form "is never more than an extension of content," then projective verse becomes also a tool for social protest. When Olson articulates the need for new recog• nitions in composing such open verse — the primary one being that the poet "can go by no other track other than the one the poem under hand declares, for itself" ( 148) — he is really under• lining the need for the poem to write itself. The poet, therefore, must be open to spontaneity of improvisation as the poem's Ufe (both in form and meaning) dictates. This means that the poem must be capable of total expression. It must be able to live on the page as well as off the page. It must be kinetic, capable of plurality, multiple perceptions, and non-linear thought. Frank O'Hara, Robert Duncan, Olson, and other Black Moun• tain poets of the 1960s used projective verse in this way. While these poets were protesting against Vietnam and compulsory draft• ing into the United States Army, black American poets, such as Amiri Baraka, were protesting also against civil rights violations ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 21:2, April 1990 46 ANTHONY KELLMAN in the United States.