Thermal Decomposition Mechanism for Ethanethiol † † † ‡ † † Angayle K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anaerobic Degradation of Methanethiol in a Process for Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) Biodesulfurization

Anaerobic degradation of methanethiol in a process for Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) biodesulfurization Promotoren Prof. dr. ir. A.J.H. Janssen Hoogleraar in de Biologische Gas- en waterreiniging Prof. dr. ir. A.J.M. Stams Persoonlijk hoogleraar bij het laboratorium voor Microbiologie Copromotor Prof. dr. ir. P.N.L. Lens Hoogleraar in de Milieubiotechnologie UNESCO-IHE, Delft Samenstelling promotiecommissie Prof. dr. ir. R.H. Wijffels Wageningen Universiteit, Nederland Dr. ir. G. Muyzer TU Delft, Nederland Dr. H.J.M. op den Camp Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen, Nederland Prof. dr. ir. H. van Langenhove Universiteit Gent, België Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool SENSE (Socio-Economic and Natural Sciences of the Environment) Anaerobic degradation of methanethiol in a process for Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) biodesulfurization R.C. van Leerdam Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 19 november 2007 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula Van Leerdam, R.C., 2007. Anaerobic degradation of methanethiol in a process for Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) biodesulfurization. PhD-thesis Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands – with references – with summaries in English and Dutch ISBN: 978-90-8504-787-2 Abstract Due to increasingly stringent environmental legislation car fuels have to be desulfurized to levels below 10 ppm in order to minimize negative effects on the environment as sulfur-containing emissions contribute to acid deposition (‘acid rain’) and to reduce the amount of particulates formed during the burning of the fuel. Moreover, low sulfur specifications are also needed to lengthen the lifetime of car exhaust catalysts. -

Category Name C2-C4 Aliphatic Thiols Category Chemical Names

SIAM 30, 20-22 April 2010 US/ICCA Category Name C2-C4 Aliphatic Thiols Category 1-Ethanethiol (CAS No. 75-08-1) Chemical Names 1-Propanethiol (CAS No.107-03-9) and CAS Nos. 1-Butanethiol (CAS No.109-79-5) 2-Propanethiol, 2-Methyl (CAS No. 75-66-1) H2 H2 C HS C C CH HS CH3 3 H2 1-Ethanethiol 1-Propanethiol (Ethyl Mercaptan) (n-Propyl Mercaptan) H H CH Structural Formulae 2 2 3 C C HS C CH 3 H3C SH H2 1-Butanethiol CH3 (n-Butyl Mercaptan) 2-Propanethiol, 2-Methyl (t-Butyl Mercaptan) SUMMARY CONCLUSIONS OF THE SIAR Category Rationale The C2-C4 Aliphatic Thiols contain a sulfhydryl (SH) functional group with a straight or branched aliphatic carbon chain that characterizes the category. The four aliphatic thiols are soluble in water and have reasonably comparable melting points, initial boiling points and vapor pressures, as well as very low and objectionable odor thresholds. The water solubility and narrow range of octanol-water partition coefficients (log Kow) for the three linear C2-C4 Aliphatic Thiols indicate that they will have similar environmental fate and are not expected to bioaccumulate in aquatic organisms. Ecotoxicity is similar for the three linear C2-C4 Aliphatic Thiols with data for fish, invertebrate and algae toxicity indicating a similar order of acute toxicity across the chemicals tested (ecotoxicity is less for t-butyl-mercaptan). ECOSAR has been used to address and support the data gaps for the linear category members. Environmental fate and toxicity data are available for the branched t-butyl mercaptan. -

8.6 Acidity of Alcohols and Thiols 355

08_BRCLoudon_pgs5-1.qxd 12/8/08 11:05 AM Page 355 8.6 ACIDITY OF ALCOHOLS AND THIOLS 355 ural barrier to the passage of ions. However, the hydrocarbon surface of nonactin allows it to enter readily into, and pass through, membranes. Because nonactin binds and thus transports ions, the ion balance crucial to proper cell function is upset, and the cell dies. Ion Channels Ion channels, or “ion gates,” provide passageways for ions into and out of cells. (Recall that ions are not soluble in membrane phospholipids.) The flow of ions is essen- tial for the transmission of nerve impulses and for other biological processes. A typical chan- nel is a large protein molecule imbedded in a cell membrane. Through various mechanisms, ion channels can be opened or closed to regulate the concentration of ions in the interior of the cell. Ions do not diffuse passively through an open channel; rather, an open channel contains regions that bind a specific ion. Such an ion is bound specifically within the channel at one side of the membrane and is somehow expelled from the channel on the other side. Remark- ably, the structures of the ion-binding regions of these channels have much in common with the structures of ionophores such as nonactin. The first X-ray crystal structure of a potassium- ion channel was determined in 1998 by a team of scientists at Rockefeller University led by Prof. Roderick MacKinnon (b. 1956), who shared the 2003 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work. The interior of the channel contains binding sites for two potassium ions; these sites are oxygen-rich, much like the interior of nonactin. -

Ethyl Mercaptan, Final AEGL Document

This PDF is available from The National Academies Press at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=18449 Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Selected Airborne Chemicals: Volume 15 ISBN Committee on Acute Exposure Guideline Levels; Committee on 978-0-309-29122-4 Toxicology; Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology; Division on Earth and Life Studies; National Research Council 294 pages 6 x 9 PAPERBACK (2013) Visit the National Academies Press online and register for... Instant access to free PDF downloads of titles from the NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL 10% off print titles Custom notification of new releases in your field of interest Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Request reprint permission for this book Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Selected Airborne Chemicals: Volume 15 Committee on Acute Exposure Guideline Levels Committee on Toxicology Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology Division on Earth and Life Studies Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Selected Airborne Chemicals: Volume 15 THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 FIFTH STREET, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Insti- tute of Medicine. -

SAFETY DATA SHEET Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc

SAFETY DATA SHEET Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Revision date 23-Dec-2016 Version 1 1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE SUBSTANCE/PREPARATION AND OF THE COMPANY/UNDERTAKING _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Product identifier Product Name Ethanethiol Product Code SC-239867 Recommended use of the chemical and restrictions on use For research use only. Not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Emergency telephone number Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Chemtrec 10410 Finnell Street 1.800.424.9300 (Within USA) Dallas, TX 75220 +1.703.527.3887 (Outside USA) 831.457.3800 800.457.3801 [email protected] 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ This chemical is considered hazardous by the 2012 OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200). Classification Acute toxicity - Oral Category 4 Acute toxicity - Dermal Category 4 Acute toxicity - Inhalation (Dusts/Mists) Category 4 Flammable liquids Category 1 Label elements Signal word Danger Hazard statements Harmful if swallowed Harmful in contact with skin Harmful if inhaled Extremely flammable liquid and vapor Symbols/Pictograms Precautionary Statements - Prevention Wash face, hands and any exposed skin thoroughly after handling Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product Wear protective gloves/protective clothing/eye protection/face protection Avoid breathing -

Recent Developments on the Origin and Nature of Reductive Sulfurous Off-Odours in Wine

fermentation Review Recent Developments on the Origin and Nature of Reductive Sulfurous Off-Odours in Wine Nikolaus Müller 1,* and Doris Rauhut 2 1 Silvanerweg 9, 55595 Wallhausen, Germany 2 Department of Microbiology and Biochemistry, Hochschule Geisenheim University, Von-Lade-Straße 1, 65366 Geisenheim, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-6706-913103 Received: 9 July 2018; Accepted: 3 August 2018; Published: 8 August 2018 Abstract: Reductive sulfurous off-odors are still one of the main reasons for rejecting wines by consumers. In 2008 at the International Wine Challenge in London, approximately 6% of the more than 10,000 wines presented were described as faulty. Twenty-eight percent were described as faulty because they presented “reduced characters” similar to those presented by “cork taint” and in nearly the same portion. Reductive off-odors are caused by low volatile sulfurous compounds. Their origin may be traced back to the metabolism of the microorganisms (yeasts and lactic acid bacteria) involved in the fermentation steps during wine making, often followed by chemical conversions. The main source of volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) are precursors from the sulfate assimilation pathway (SAP, sometimes named as the “sulfate reduction pathway” SRP), used by yeast to assimilate sulfur from the environment and incorporate it into the essential sulfur-containing amino acids methionine and cysteine. Reductive off-odors became of increasing interest within the last few years, and the method to remove them by treatment with copper (II) salts (sulfate or citrate) is more and more questioned: The effectiveness is doubted, and after prolonged bottle storage, they reappear quite often. -

I. a Mechanistic Study of the Hydrodesulfurization of Methanethiol Over Tungsten Disulfide; II

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1985 I. A mechanistic study of the hydrodesulfurization of methanethiol over tungsten disulfide; II. A urs vey of rare earth sulfides for yh drodesulfurization activity Donald Quinn Dowd Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Physical Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Dowd, Donald Quinn, "I. A mechanistic study of the hydrodesulfurization of methanethiol over tungsten disulfide; II. A survey of rare earth sulfides for hydrodesulfurization activity " (1985). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7842. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7842 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. -

Corrosive Properties of LPG and Problems with Their Determination

The Archives of Automotive Engineering – Archiwum Motoryzacji Vol. 74, No. 4, 2016 7 Article citation info: Bukrejewski P, Wardzińska D, Skolniak M. Corrosive properties of LPG and problems with their determination. The Archives of automotive Engineering – Archiwum Motoryzacji. 2016; 74(4): 7-17, http://dx.doi.org/10.14669/ AM.VOL74.ART1 CORROSIVE PROPERTIES OF LPG AND PROBLEMS WITH THEIR DETERMINATION PAWEŁ BUKREJEWSKI1, DOROTA WARDZIŃSKA2, MARTA SKOLNIAK3 Automotive Industry Institute (PIMOT) Summary The corrosiveness of gaseous fuels is a known and frequently encountered problem, but the methods employed to explore this issue not always lead to the obtaining of reliable results. This article presents results of interlaboratory comparisons carried out to verify the method of evaluation of the corrosiveness of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) according to Standard PN-EN ISO 6251. The corrosiveness of LPG to copper was tested for four different samples of the LPG fuel. Keywords: LPG, coper corrosion, degree of corrosion 1. Introduction The liquefied hydrocarbon gas, referred to as LPG (liquefied petroleum gas), is the Poland’s most popular alternative fuel [3]. Both in the production process and during transport, this fuel is exposed to the impact of many unfavourable factors. The LPG quality is particu- larly jeopardized during the transhipment processes in transport, when this fuel may be exposed to the penetration of such substances as water and sulphur compounds into it. The contaminants present in LPG may cause corrosion of the structural materials being in contact with this fuel, e.g. fuel system components, gasholders, or transmission instal- lations. The solid products of corrosion processes are mechanical contaminants, which, having penetrated with the fuel into the gas feeding system of a vehicle, may cause dam- age to system components [1, 6]. -

Commercially Available Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts for Winemaking: Current Market, Advantages Over Saccharomyces, Biocompatibility, and Safety

fermentation Review Commercially Available Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts for Winemaking: Current Market, Advantages over Saccharomyces, Biocompatibility, and Safety Ricardo Vejarano 1,* and Angie Gil-Calderón 2 1 Dirección de Investigación y Desarrollo, Universidad Privada del Norte (UPN), Trujillo 13001, Peru 2 Ingeniería Agroindustrial, Universidad Privada del Norte (UPN), Trujillo 13001, Peru; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: About 42 commercial products based on non-Saccharomyces yeasts are estimated as avail- able on the market, being mostly pure cultures (79%), with a predominance of Torulaspora delbrueckii, Lachancea thermotolerans, and Metschnikowia pulcherrima. The others are multi-starter consortia that include non-Saccharomyces/Saccharomyces mixtures or only non-Saccharomyces species. Several com- mercial yeasts have shown adequate biocompatibility with S. cerevisiae in mixed fermentations, allowing an increased contribution of metabolites of oenological interest, such as glycerol, esters, higher alcohols, acids, thiols, and terpenes, among others, in addition to a lower production of acetic acid, volatile phenols, biogenic amines, or urea. Multi-starter inoculations are also reviewed here, which show adequate biocompatibility and synergy between species. In certain cases, the aromatic profile of wines based on grape varieties considered neutral is improved. In addition, several yeasts show the capacity as biocontrollers against contaminating microorganisms. The studies conducted to Citation: Vejarano, R.; Gil-Calderón, A. Commercially date demonstrate the potential of these yeasts to improve the properties of wine as an alternative and Available Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts complement to the traditional S. cerevisiae. for Winemaking: Current Market, Advantages over Saccharomyces, Keywords: commercial non-Saccharomyces yeasts; winemaking; biocompatibility; wine quality Biocompatibility, and Safety. -

Ethyl Mercaptan Hazard Summary Identification

Common Name: ETHYL MERCAPTAN CAS Number: 75-08-1 RTK Substance number: 0894 DOT Number: UN 2363 Date: March 1999 ----------------------------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------------------------- HAZARD SUMMARY * Ethyl Mercaptan can affect you when breathed in and requires private employers to provide similar training and may be absorbed through the skin. information to their employees. * Contact can cause skin and eye irritation. * Breathing Ethyl Mercaptan can irritate the nose and * Exposure to hazardous substances should be routinely throat. evaluated. This may include collecting personal and area * Breathing Ethyl Mercaptan can irritate the lungs causing air samples. You can obtain copies of sampling results coughing and/or shortness of breath. Higher exposures from your employer. You have a legal right to this can cause a build-up of fluid in the lungs (pulmonary information under OSHA 1910.1020. edema), a medical emergency, with severe shortness of * If you think you are experiencing any work-related health breath. problems, see a doctor trained to recognize occupational * Breathing Ethyl Mercaptan can cause headache, nausea, diseases. Take this Fact Sheet with you. vomiting, diarrhea, muscle weakness, convulsions, and * ODOR THRESHOLD = 0.00035 ppm. tiredness. Higher levels can cause dizziness, * The range of accepted odor threshold values is quite lightheadedness, coma and death. broad. Caution should be used in relying on odor alone as * Ethyl Mercaptan may damage the liver and kidneys. a warning of potentially hazardous exposures. * Repeated or long term exposure to Ethyl Mercaptan may damage the red blood cells causing anemia. WORKPLACE EXPOSURE LIMITS * Ethyl Mercaptan is a HIGHLY FLAMMABLE LIQUID OSHA: The legal airborne permissible exposure limit or GAS and a DANGEROUS FIRE HAZARD. -

Chemicals Requiring EHS Pre-Approval

Chemicals Requiring EHS Approval Before Purchasing Chemical Name CAS # 1,3-Bis(2-chloroethylthio)-n-propane 63905-10-2 1,4-Bis(2-chloroethylthio)-n-butane 142868-93-7 1,5-Bis(2-chloroethylthio)-n-pentane 142868-94-8 1H-Tetrazole 288-94-8 2-chloroethyl ethylsulfide 693-07-2 2-Chloroethylchloro-methylsulfide 2625-76-5 2-Cyanoethyl diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite 89992-70-1 2-Ethoxyethanol 110-80-5 2-Ethoxyethylacetate 111-15-9 2-Methoxyethanol 109-86-4 2-Methoxyethylacetate 110-49-6 5-Nitrobenzotriazol 2338-12-7 Acetone cyanohydrin, stabilized 75-86-5 Acrolein 107-02-8 Acrylamide (powder) 79-06-1 Allylamine 107-11-9 Aluminum (powder) 7429-90-5 Aluminum phosphide 20859-73-8 Ammonia 7664-41-7 Ammonium nitrate 6484-52-2 Ammonium perchlorate 7790-98-9 Ammonium picrate 131-74-8 Arsenic 7440-38-2 Arsenic trichloride 7784-34-1 Arsenic trioxide 1327-53-3 Arsine 7784-42-1 Barium azide 18810-58-7 Beryllium 7440-41-7 Bis(2-chloroethylthio)methane 63869-13-6 Bis(2-chloroethylthiomethyl)ether 63918-90-1 Boron tribromide 10294-33-4 Boron trichloride 10294-34-5 Boron trifluoride 7637-07-2 Bromine 7726-95-6 Bromine chloride 13863-41-7 Bromine pentafluoride 7789-30-2 Bromine trifluoride 7787-71-5 Cadmium 7440-43-9 Calcium phosphide 1305-99-3 Carbon monoxide 630-08-0 Carbonyl fluoride 353-50-4 Carbonyl sulfide 463-58-1 Chlorine 7782-50-5 Chlorine dioxide 10049-04-4 Chlorine pentafluoride 13637-63-3 Chlorine trifluoride 7790-91-2 Chemicals Requiring EHS Approval Before Purchasing Chloroacetyl chloride 79-04-9 Chlorosarin 1445-76-7 Chlorosoman 7040-57-5 Chlorosulfonic -

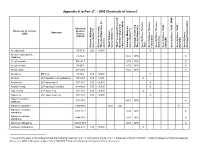

Appendix a to Part 27

Appendix A to Part 27. – DHS Chemicals of Interest1 - - - WME - - – – Chemical Chemicals of Interest Abstract Synonym (COI) Service (CAS) # y Issue: Theft Theft y Issue: Screening Threshold Threshold Screening EXP/IEDP Issue: Security Sabotage/Contamination Security Issue: Theft Theft Issue: Security CWI/CWP Theft Issue: Security Release: Minimum Minimum Release: (%) Concentration Screening Release: (in Quantities Threshold pounds) Theft: Minimum (%) Concentration Theft: pounds (in Quantities noted) otherwise unless Minimum Sabotage: (%) Concentration Screening Sabotage: Quantities Threshold Release Issue: Security Toxic Release Issue: Security Flammables Release Issue: Security Explosives Securit Acetaldehyde 75-07-0 1.00 10,000 X Acetone cyanohydrin, 75-86-5 ACG APA X stabilized Acetyl bromide 506-96-7 ACG APA X Acetyl chloride 75-36-5 ACG APA X Acetyl iodine 507-02-8 ACG APA X Acetylene [Ethyne] 74-86-2 1.00 10,000 X Acrolein [2-Propenal] or Acrylaldehyde 107-02-8 1.00 5,000 X Acrylonitrile [2-Propenenitrile] 107-13-1 1.00 10,000 X Acrylyl chloride [2-Propenoyl Chloride] 814-68-6 1.00 10,000 X Allyl alcohol [2-Propen-1-ol] 107-18-6 1.00 15,000 X Allylamine [2-Propen-1-amine] 107-11-9 1.00 10,000 X Allyltrichlorosilane, 107-37-9 ACG APA X stabilized Aluminum (powder) 7429-90-5 ACG 100 X Aluminum bromide, 7727-15-3 ACG APA X anhydrous Aluminum chloride, 7446-70-0 ACG APA X anhydrous Aluminum phosphide 20859-73-8 ACG APA X Ammonia (anhydrous) 7664-41-7 1.00 10,000 X 1 The acronyms used in this appendix have the following meaning: ACG