Incursion Into Wendigo Territory Jackson Eflin, Ball Sate University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Postmodernisms, Hauntology and Creepypasta Narratives As Digital

Spectres des monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction ONDRAK, Joe Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/23603/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version ONDRAK, Joe (2018). Spectres des monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction. Horror Studies, 9 (2), 161-178. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Spectres des Monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction Joe Ondrak, Sheffield Hallam University Abstract Horror has always been adaptable to developments in media and technology; this is clear in horror tales from Gothic epistolary novels to the ‘found footage’ explosion of the early 2000s via phantasmagoria and chilling radio broadcasts such as Orson Welles’ infamous War of the Worlds (1938). It is no surprise, then, that the firm establishment of the digital age (i.e. the widespread use of Web2.0 spaces the proliferation of social media and its integration into everyday life) has created venues not just for interpersonal communication, shared interests and networking but also the potential for these venues to host a new type of horror fiction: creepypasta. However, much of the current academic attention enjoyed by digital horror fiction and creepypasta has focused on digital media’s ability to remediate a ‘folk-like’ storytelling style and an emulation of word-of-mouth communication primarily associated with urban legends and folk tales. -

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: a Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: A Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905 by Fadi Saleem Ennab A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Fadi Saleem Ennab TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................... 8 Mythologizing the Frontier .......................................................................................... 8 Comparative and Critical Studies on Western Canada .......................................... 15 Studies of Colonial Policing and Violence in Other British Colonies .................... 22 Summary of Literature ............................................................................................... 32 Research Questions ..................................................................................................... 33 CHAPTER THREE: THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................... 35 CHAPTER -

Geol on the Three Islands Cl Groups

52E09SE8a85 2.8340 WHITEFISH BAY AND MA 010 GEOLOGICAL REPORT ON THE THREE ISLANDS CLAIM GROUPS LAKE OF THE WOODS, KENORA DISTRICT, ONTARIO N.T.S. 52E/9SW by ULRICH KRETSCHMAR, Ph.D. PATRICK CHEVALIER, B.Se. Prepared for BIGSTONE MINERALS LTD 8 KING STREET EAST, SUITE 1703 TORONTO, ONTARIO M5C 1B5 SEPTEMBER 1984 DIANNE SL ULRICH KRETSCHMAR Geologists R.R.*1. Severn Bridge, Ontario, POE 1NO, Canada (705)689-6431 SUMMARY Three properties: Jenny Leigh, Hay Island and Scotty Island were examined on Lake of the Woods. There are a large number of gold showings and current interest is generally the result of spillover from Nuinsco©s discovery of about l million tons, grading 0.20 oz/ton gold in the Cameron Lake area, about 50 km to southeast. A total of 40 man days were spent on geological mapping, sampling and report preparation on the three properties by Ulrich Kretschmar in August and September. There is a close similarity between the geology of the Jenny Leigh property and the adjacent Wendigo Mine where about 200,000 tons grading 0.33 oz/ton gold and 9.2X copper were produced during 1900-195}.. The value of this production would be about $30 million dollars at current metal prices. Major lithologies consist of mafic volcanics and interbedded differentiated ultramafic flows of probably komatiitic affinity. These are folded in a series of tight isoclinal drag folds on the Wendigo property and the mine horizon is repeated by a major east-west trending syncline on the Jenny-Leigh property. Mineralization on both the Jenny-Leigh property and at the Wendigo Mine occurs in gold-bearing conformable siliceous, locally graphitic interflow sediments. -

Cannibalism in Contact Narratives and the Evolution of the Wendigo Michelle Lietz

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 3-1-2016 Cannibalism in contact narratives and the evolution of the wendigo Michelle Lietz Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lietz, Michelle, "Cannibalism in contact narratives and the evolution of the wendigo" (2016). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 671. http://commons.emich.edu/theses/671 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cannibalism in Contact Narratives and the Evolution of the Wendigo by Michelle Lietz Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Language and Literature Eastern Michigan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Literature Thesis Committee: Abby Coykendall, Ph.D., First Reader Lori Burlingame, Ph.D., Second Reader March 1, 2016 Ypsilanti, Michigan ii Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my kind and caring sisters, and my grounding father. For my mother: thank you for beginning my love of words and for every time reading “one more chapter.” And for every person who has reminded me to guard my spirit during long winters. iii Acknowledgments I am deeply indebted to Dr. Lori Burlingame, for reading all of my papers over and over again, for always letting me take up her office hours with long talks about Alexie, Erdrich, Harjo, Silko and Ortiz, and supporting everything I’ve done with unwavering confidence. -

Evolution of the Youtube Personas Related to Survival Horror Games

Toniolo EVOLUTION OF THE YOUTUBE PERSONAS RELATED TO SURVIVAL HORROR GAMES FRANCESCO TONIOLO CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF MILAN ABSTRACT The indie survival horror game genre has given rise to some of the most famous game streamers on YouTube, especially titles likes Amnesia: The Dark Descent (Frictional Games 2010), Slender: The Eight Pages (Parsec Productions 2012), and Five Nights at Freddy’s (Scott Cawthon 2014). The games are strongly focused on horror tropes including jump scares and defenceless protagonists, which lend them to displays of overemphasised emotional reactions by YouTubers, who use them to build their online personas in a certain way. This paper retraces the evolution of the relationship between horror games and YouTube personas, with attention to in-game characters and gameplay mechanics on the one hand and the practices of prominent YouTube personas on the other. It will show how the horror game genre and related media, including “Let’s play” videos, animated fanvids, and “creepypasta” stories have influenced prominent YouTuber personas and resulted in some changes in the common processes of persona formation on the platform. KEY WORDS Survival Horror; Video Game; YouTube; Creepypasta; Fanvid; Let’s Play INTRODUCTION Marshall & Barbour (2015, p. 7) argue that “Game culture consciously moves the individual into a zone of production and constitution of public identity”. Similarly, scholars have studied – with different foci and levels of analysis – the relationships between gamers and avatars in digital worlds or in tabletop games by using the concept of “persona” (McMahan 2003; Waskul & Lust 2004; Isbister 2006; Frank 2012). Often, these scholars were concerned with online video games such as World of Warcraft (Filiciak 2003; Milik 2017) or famous video game icons like Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider series (McMahan 2008). -

Creepypasta – the Modern Twist in Horror Literature

„Kwartalnik Opolski” 2016, 4 Przemysław SIEK Creepypasta – the modern twist in horror literature The 21st century saw humanity making great advancements in many fields, such as medicine or science, none however has had as great an impact as the rise of the Internet. Ever since it was open to the general public, there have been many debates as to whether it is a useful tool which gives us endless possibilities, or perhaps a means of turning people into mindless, antisocial zombies. Although one could find arguments to justify both of these claims, it is true that as technology is developing, people appear to be less inclined to read. This is demonstrated in a study conducted by Jessica E. Moyer entitled “Teens Today Don’t Read Books Anymore”1 among many others. If this is the case, can we say that using the Internet leads to illiteracy and portends the fall of literature? Not quite. As we all know, everything depends on how we use the tools we are given – and such is the case here. A truly remarkable example of how the Internet can lead to popularizing both reading and writing, and even contribute to literature itself appeared several years ago. It is known as Creepypasta and has unfortunately been rarely discussed in the media (only a few articles have been published so far), and almost completely ignored by literary scholars. In the past, literature was passed down orally – this is mirrored by how Creepypastas circulate. The only difference is that the voice of a story- teller has been replaced by electronic communication devices. -

Widening the Angle: Film As Alternative Pedagogy for Wellness in Indigenous Youth

International Journal of Education & the Arts Editors Christopher M. Schulte Peter Webster University of Arkansas University of Southern California Eeva Anttila Mei-Chun Lin University of the Arts Helsinki National University of Tainan http://www.ijea.org/ ISSN: 1529-8094 Volume 21 Number 1 January 6, 2019 Widening the Angle: Film as Alternative Pedagogy For Wellness In Indigenous Youth Warren Linds Concordia University, Canada Sandra Sjollema Concordia University, Canada Janice Victor University of Lethbridge, Canada Lacey Eninew Lac La Ronge Indian Band, Canada Linda Goulet First Nations University of Canada, Canada Citation: Linds, W., Sjollema, S., Victor, J., Eninew, L., & Goulet, L. (2020). Widening the angle: Film as alternative pedagogy for wellness in Indigenous youth. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 21(1). Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.26209/ijea21n1. IJEA Vol. 21 No. 1 - http://www.ijea.org/v21n1/ 2 Abstract Indigenous youth face numerous challenges in terms of their well-being. Colonization enforced land and cultural loss, fractured relationships, and restricted the use of the imagination and agentic capacity (Colonial policies, structures, and approaches in education have been detrimental to Indigenous youth (Nardozi, 2013). Many First Nations leaders, community members, and youth have expressed a need for a wider range of activities that move beyond Western models of knowledge and learning (Goulet & Goulet, 2015). School curricula in Indigenous communities are incorporating alternative pedagogical tools, such as the arts, that not only allow youth to explore and express their realities and interests but that also offer them holistic ways of learning and knowing (Yuen et al., 2013). This article describes a participatory arts research project which featured film production and was delivered in the context of a grade 10 Communications Media course. -

Of Internet Born: Idolatry, the Slender Man Meme, and the Feminization of Digital Spaces

Feminist Media Studies ISSN: 1468-0777 (Print) 1471-5902 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfms20 Of Internet born: idolatry, the Slender Man meme, and the feminization of digital spaces Jessica Maddox To cite this article: Jessica Maddox (2018) Of Internet born: idolatry, the Slender Man meme, and the feminization of digital spaces, Feminist Media Studies, 18:2, 235-248, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2017.1300179 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1300179 Published online: 15 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 556 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfms20 FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES, 2018 VOL. 18, NO. 2, 235–248 https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1300179 Of Internet born: idolatry, the Slender Man meme, and the feminization of digital spaces Jessica Maddox Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, The University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This paper examines 96 US and British Commonwealth articles on the Received 31 May 2016 2014 Wisconsin Slender Man stabbing. Using critical textual analysis, Revised 28 October 2016 this study examined how media took a horror-themed meme from Accepted 29 January 2017 the underbelly of the Internet and curated a moral panic, once the KEYWORDS meme was thrust into the international limelight. Because memes are Memes; Internet; idolatry; a particular intersection of images and technology, media made sense Slender Man; technology; of this meme-inspired attack in three ways: (1) through an idolatrous feminism tone that played on long-standing Western anxieties over images; (2) by hyper-sensationalizing women’s so-called frivolous uses of technology; and (3) by removing blame from the assailants and, in turn, finding the Internet and the Slender Man meme guilty in the court of public opinion. -

The Wetiko Legal Principles: Cree and Anishinabek Responses to Violence and Victimization by Hadley Louise Friedland

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Volume 57 Issue 2 Volume 57, Issue 2 (Fall 2020) Article 7 1-14-2021 The Wetiko Legal Principles: Cree and Anishinabek Responses to Violence and Victimization by Hadley Louise Friedland Natasha Novac Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Law Commons Book Review Citation Information Novac, Natasha. "The Wetiko Legal Principles: Cree and Anishinabek Responses to Violence and Victimization by Hadley Louise Friedland." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 57.2 (2021) : 510-518. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol57/iss2/7 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. The Wetiko Legal Principles: Cree and Anishinabek Responses to Violence and Victimization by Hadley Louise Friedland Abstract Can we reject a monstrous act without rejecting the actor as a monster? This is the question occupying Hadley Louise Friedland, Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Alberta, in The Wetiko Legal Principles: Cree and Anishinabek Responses to Violence and Victimization. Speaking broadly, the book is dedicated to identifying and examining Indigenous laws for guidance on how Indigenous communities can deal with high rates of interpersonal violence in Indigenous communities today, particularly violence against children. The innovation in Friedland’s work is her creative use of source material: She takes as her starting point traditional Cree and Anishinabek stories about wetikos, or cannibal giants, which she positions as vestibules of Indigenous law. -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Fear Has No Face: Creepypasta as Digital Legendry Trevor J. Blank and Lynne S. McNeill 3 1 “The Sort of Story That Has You Covering Your Mirrors”: The Case of Slender Man Jeffrey A. Tolbert 25 2 The Cowl of Cthulhu: Ostensive Practice in the Digital Age Andrew Peck 51 3 “What Happens When the Pictures Are No Longer Photoshops?” Slender Man, Belief, and the Unacknowledged Common Experience Andrea Kitta 77 4 “Dark and Wicked Things”: Slender Man, the Folkloresque, and the Implications of Belief Jeffrey A. Tolbert 91 5 The Emperor’s New Lore; or, Who Believes in the Big Bad Slender Man? Mikel J. Koven 113 6 Slender COPYRIGHTEDMan, H. P. Lovecraft, and the MATERIALDynamics of Horror Cultures NOTTimothy FOR H. EvansDISTRIBUTION 128 7 Slender Man Is Coming to Get Your Little Brother or Sister: Teenagers’ Pranks Posted on YouTube Elizabeth Tucker 141 8 Monstrous Media and Media Monsters: From Cottingley to Waukesha Paul Manning 155 Notes on the Authors 183 Index 185 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION Figure 0.1. Original caption: “One of two recovered photographs from the Stirling City Library blaze. Notable for being taken the day which fourteen chil- dren vanished and for what is referred to as ‘The Slender Man’. Deformities cited as film defects by officials. Fire at library occurred one week later. Actual photograph confiscated as evidence.—1986, photographer: Mary Thomas, missing since June 13th, 1986.” (http://knowyourmeme.com/memes /slender-man.) Introduction Fear Has No Face Creepypasta as Digital Legendry Trevor J. Blank and Lynne S. -

What Makes the Foundation Seem So Realistic? How Is T

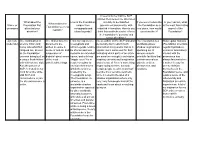

It seems to me that the SCP articles themselves are structured What about the How is the Foundation similarly to declassified If you were to describe In your opinion, what What makes the Name or Foundation first unique from government documents, with the Foundation as a is the most fascinating Foundation seem so username attracted your creepypasta and redacted information. How do you real place, how would aspect of the realistic? attention? urban legends? think this aesthetic choice effects you describe it? Foundation? the Foundation's 'persona' and sense of realism? Zyn (site The combination of The clinical tone the From my experience, I'm an author on the SCP wiki and I The Foundation is a How regular humans moderator) science fiction and documents are creepypasta and personally don't redact much worldwide-power (Foundation scientists, horror was what first written in evoke a urban legends tend to information in my works, but as a shadow organization regular bystanders, intrigued me, as well sense of realism and be shorter and less stylistic tool it works well for both operating out of victims of anomalies) as the Foundation suspension of rooted in an extended indicating which parts of an article various esoteric interact with the universe being built on disbelief about some canon, and with less are sensitive enough to be hidden, scientific facilities that anomalous has a unique flash-fiction- of the most "wiggle room" for a inspiring curiosity and imagination contain anomalous always fascinated me. with-clinical-tone style. unbelievable things. reader or author to and a sense of "there's something objects, entities, It makes it easy for Also the picture of envision themselves bigger going on here, but only phenomena, and one to envision SCP-173 stuck in my within the universe certain people need to know that". -

Baring the Windigo's Teeth: the Fearsome Figure in Native

Baring the Windigo’s Teeth: The Fearsome Figure in Native American Narratives Carol Edelman Warrior A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Docrtor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: 1 Brian M. Reed, Chair Dian Million Christopher Teuton Luana Ross Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of English © Copyright 2015 Carol Edelman Warrior University of Washington Abstract Baring the Windigo’s Teeth: Fearsome Figures in Native American Narratives Carol Edelman Warrior Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Brian M. Reed Department of English Whereas non-Native American fictional fearsome figures tend to produce anxiety from their resistance to categorization, their unpredictable movement, and their Otherness, many contemporary Native American writers re-imagine fearsome figures and monstrous systems as modeled after, and emergent from settler-colonial transgressions against Indigenous values and relationships: these behaviors spread to tribal people/s through incorporation or assimilation into the “body” of the fearsome figure. Such violations can be represented by, and better understood, through an exploration of the behavioral traits of the Algonquian figure of the 2 Windigo, or wétiko, even when the text in question would not be classified as horror. In the Indigenous works of fiction that this dissertation explores, villainy is depicted as behavior that destroys balance, and disrupts the ability for life to reproduce itself without human mediation or technological intervention. In this dissertation, I develop and apply “Windigo Theory”: an Indigenous literary approach to reading Indigenous fiction, especially intended to aid recognition and comprehension of cultural critiques represented by the fearsome figures.