Downloaded From: Version: Accepted Version Publisher: Taylor & Francis DOI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Leveson Inquiry Into the Cultures, Practices And

For Distribution to CPs THE LEVESON INQUIRY INTO THE CULTURES, PRACTICES AND ETHICS OE THE PRESS WITNESS STATEMENT OE JAMES HANNING I, JAMES HANNING of Independent Print Limited, 2 Derry Street, London, W8 SHF, WILL SAY; My name is James Hanning. I am deputy editor of the Independent on Sunday and, with Francis Elliott of The Times, co-author of a biography of David Cameron. In the course of co-writing and updating our book we spoke to a large number of people, but equally I am very conscious that I, at least, dipped into areas in which I can claim very little specialist knowledge, so I would emphasise that in several respects there are a great many people better placed to comment and much of what follows is impressionistic. I hope that what follows is germane to some of the relationships that Lord Justice Leveson has asked witnesses to discuss. I hesitate to try to draw a broader picture, but I hope that some conclusions about the disproportionate influence of a particular sector of the media can be drawn from my experience. My interest in the area under discussion in the Third Module stems from two topics. One is in David Cameron, on whose biography we began work in late 2005, soon after Cameron became Tory leader. The second is an interest in phone hacking at the News of the World. Tory relations with Murdoch Since early 2007, the Conservative leadership has been extremely keen to ingratiate itself with the Murdoch empire. It is striking how it had become axiomatic that the support of the Murdoch papers was essential for winning a general election. -

Mandy Tranter CV 2018

MANDY TRANTER 07773 421 913 // [email protected] // LINKEDIN.COM/IN/MANDYTRANTER BROADCAST PROFILE Our Guy in China I am a freelance Editor with 17 years experience of working in broadcast television. The Gadget Show My Kitchen Rules UK My creativity and technical knowledge have enabled me to pursue an exciting career. Having been employed as a staff editor for 6 years I decided to become a Do You Know? freelance offline editor and now enjoy working on a wide range of programmes. The Jury Room My editor credits include Our Guy In China (CH4), The Gadget Show (Channel 5), Operation Ouch Fifth Gear (Discovery), My Kitchen Rules UK (CH4), The Street That Cut Everything (BBC1) and the Royal Shakespeare Company for cinema broadcast features on Garden Rescue King Lear, Cymbeline & Henry V. The Instant Gardener Guy Martin's Spitfire WORK House That 100K Built OFFLINE EDITOR // ROYAL SHAKESPEARE COMPANY // 2018 Give A Pet A Home NATIONWIDE CINEMA BROADCAST FEATURES FOR TWELFTH NIGHT Fifth Gear The Street That Cut Everything OFFLINE EDITOR // DAISYBECK STUDIOS // 2017 I Didn’t Know That HARROGATE: A GREAT YORKSHIRE CHRISTMAS (Channel 5) Speed With Guy Martin OFFLINE EDITOR // 7 WONDER // 2017 How Britain Worked MY KITCHEN RULES UK, SERIES 2 (CH4) Big Strong Boys Star Portraits OFFLINE EDITOR // 7 WONDER // 2017 Soul Boy (RTS Award Winner) DO YOU KNOW?, SERIES 2 (CBeebies) Everything Must Go OFFLINE EDITOR // First Look TV // 2017 Points Of View THE JURY ROOM (CBS Reality) EXPERTISE OFFLINE EDITOR // NORTH ONE TV // 2016 Avid Media Composer OUR -

Second Strike Gearing Calculator

Second Strike October 31 and December 31, 2002 The Newsletter for the Superformance Owners Group Page 1 SECOND STRIKE GEARING CALCULATOR The Second Strike Gearing Calculator Transmission Mk III Coupe GT Ford Toploader Yes 4-speed (close ratio) Ford Toploader Yes 4-speed (wide ratio) RBT 5-speed Yes (transaxle) Rear Axle Ratio BTR Rear Axle Ford 8.8 RBT Coupe Ratio Mk III GT Mk III 3.08 Yes 3.27 Yes 3.46 Yes 3.55 Yes 3.73 Yes 3.77 Yes 3.91 Yes 4.10 Yes 4.30 Yes 4.56 Yes The Ford 8.8 IRS (independent rear suspension) rear end is used in MK III’s prior to chassis number 2068. The BTR is To assist owners in evaluating transmission, rear end ratio, and used in the Mk III from chassis 2068 on. tire combinations, an interactive gearing calculator has been added to the Second Strike web site (www.SecondStrike.com). Tire Size Mk III Coupe GT The calculator is designed to help you analyze contemplated Common 275/60-15 285/50-18 275/60-15 changes and get it right before committing your hard earned Tire Sizes 295/50-15 295/45-18 295/50-15 bucks. Changing the transmission, rear end, or rim size is not 335/35-17 315/35-18 for the faint of heart or thin of wallet. The “standard” tire size is shown first. Other commonly used Input Section sizes are also shown. The Gearing Calculator supports the most commonly used transmissions, rear ends and tire sizes used for the 275/60-15 is a 275 width, 60 aspect ratio, and 15” rim Superformance Mk III, Coupe, and GT. -

October 2019 50P Are You Ready? Brexit Looms

Issue 421 October 2019 50p Are you ready? Brexit looms ... & Chippy looks to the future Parliament is in turmoil and Chipping Norton, with the nation, awaits its fate, as the Mop Magic! Government plans to leave the EU on 31 October – Deal or No Deal. So where next? Is Chippy ready? It’s all now becoming real. Will supplies to Chippy’s shops and health services be disrupted? Will our townsfolk, used to being cut off in the snow, stock up just in case? Will our businesses be affected? Will our EU workers stay and feel secure? The News reports from around Chippy on uncertainty, contingency plans, but also some signs of optimism. Looking to the future – Brexit or not, a positive vision for Chippy awaits if everyone can work together on big growth at Tank Farm – but with the right balance of jobs, housing mix, and environmental sustainability for a 21st century Market town – and of course a solution to those HGV and traffic issues. Chipping Norton Town Council held a lively Town Hall meeting in September, urging the County Council leader, Ian Hudspeth into action to work with them. Lots more on Brexit, HGVs, and all this on pages 2-3. News & Features in this Issue • GCSE Results – Top School celebrates great results • Health update – GPs’ new urgent care & appoint- ment system • Cameron book launch – ‘For the Record’ • Chipping Norton Arts Festival – 5 October The Mop Fair hit town in • Oxfordshire 2050 – how will Chippy fit in? September – with everyone • Climate emergency – local action out having fun, while the traffic Plus all the Arts, Sports, Clubs, Schools and Letters went elsewhere. -

Pressreader Magazine Titles

PRESSREADER: UK MAGAZINE TITLES www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader Computers & Technology Sport & Fitness Arts & Crafts Motoring Android Advisor 220 Triathlon Magazine Amateur Photographer Autocar 110% Gaming Athletics Weekly Cardmaking & Papercraft Auto Express 3D World Bike Cross Stitch Crazy Autosport Computer Active Bikes etc Cross Stitch Gold BBC Top Gear Magazine Computer Arts Bow International Cross Stitcher Car Computer Music Boxing News Digital Camera World Car Mechanics Computer Shopper Carve Digital SLR Photography Classic & Sports Car Custom PC Classic Dirt Bike Digital Photographer Classic Bike Edge Classic Trial Love Knitting for Baby Classic Car weekly iCreate Cycling Plus Love Patchwork & Quilting Classic Cars Imagine FX Cycling Weekly Mollie Makes Classic Ford iPad & Phone User Cyclist N-Photo Classics Monthly Linux Format Four Four Two Papercraft Inspirations Classic Trial Mac Format Golf Monthly Photo Plus Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Mac Life Golf World Practical Photography Classic Racer Macworld Health & Fitness Simply Crochet Evo Maximum PC Horse & Hound Simply Knitting F1 Racing Net Magazine Late Tackle Football Magazine Simply Sewing Fast Bikes PC Advisor Match of the Day The Knitter Fast Car PC Gamer Men’s Health The Simple Things Fast Ford PC Pro Motorcycle Sport & Leisure Today’s Quilter Japanese Performance PlayStation Official Magazine Motor Sport News Wallpaper Land Rover Monthly Retro Gamer Mountain Biking UK World of Cross Stitching MCN Stuff ProCycling Mini Magazine T3 Rugby World More Bikes Tech Advisor -

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Host on 'Worst Year'

7 Ts&Cs apply Iceland give huge discount Claire King health: Craig Revel Horwood Kate Middleton pregnant Jenny Ryan: ‘The cat is out to emergency service Emmerdale star's health: ‘It was getting with twins on royal tour in the bag’ The Chase quizzer workers - find… diagnosis ‘I was worse’ Strictly… Pakistan?… announces… Jeremy Clarkson: ‘Wanted to top myself’ Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on 'worst year' JEREMY CLARKSON - who fronts ITV show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? - shared his thoughts on a recent study which claimed 1978 was the “worst year” in British history. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire: Jeremy criticises the contestant Earlier this week, researchers from Warwick University claimed people of Britain were at their most unhappy in 1978. The latter year and the first two months of 1979 are best remembered for the Winter of Discontent, where strikes took place and caused various disruptions. ADVERTISING 1/6 Jeremy Clarkson (/search?s=jeremy+clarkson) shared his thoughts on the study as he recalled his first year of working during the strikes. PROMOTED STORY 4x4 Magazine: the SsangYong Musso is a quantum leap forward (SsangYong UK)(https://www.ssangyonggb.co.uk/press/first-drive-ssangyong-musso/56483&utm-source=outbrain&utm- medium=musso&utm-campaign=native&utm-content=4x4-magazine?obOrigUrl=true) In his column with The Sun newspaper, he wrote: “It’s been claimed that 1978 was the worst year in British history. RELATED ARTICLES Jeremy Clarkson sports slimmer waistline with girlfriend Lisa Jeremy Clarkson: Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on his Hogan weight loss (/celebrity-news/1191860/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-girlfriend- (/celebrity-news/1192773/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-health- Lisa-Hogan-pictures-The-Grand-Tour-latest-news) Who-Wants-To-Be-A-Millionaire-age-ITV-Twitter-news) “I was going to argue with this. -

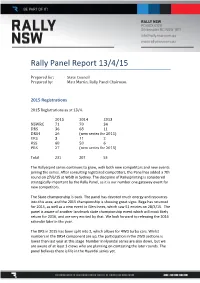

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

The Puzzle of Media Power: Notes Toward a Materialist Approach

International Journal of Communication 8 (2014), 319–334 1932–8036/20140005 The Puzzle of Media Power: Notes Toward a Materialist Approach DES FREEDMAN Goldsmiths, University of London In any consideration of the relationship between communication and global power shifts and of the ways in which the media are implicated in new dynamics of power, the concept of media power is frequently invoked as a vital agent of social and communicative change. This article sets out to develop a materialist approach to media power that acknowledges its role in social reproduction through the circulation of symbolic goods but suggests that we also need an understanding of media power that focuses on the relationships between actors, institutions, and contexts that organize the allocation of material resources concentrated in the media. It is hardly controversial to suggest that the media are powerful social actors, but what is the nature of this power? Does it refer to people, institutions, processes, or capacities? If we are to understand the role of communication as it relates to contemporary circumstances of neoliberalism, globalization, cosmopolitanism, and digitalization (which this special section sets out to consider), then we need a definition of media power that is sufficiently complex and robust to evaluate its channels, networks, participants, and implications. This article suggests that, just as power is not a tangible property visible only in its exercise, media power is best conceived as a relationship between different interests engaged in struggles for a range of objectives that include legitimation, influence, control, status, and, increasingly, profit. Strangely, one of the clearest metaphors for media power in recent years involves a horse. -

Highlight Der Woche: Top Gear Eps. 1

DMAX Programm Programmwoche 36, 01.09. bis 07.09.2012 Highlight der Woche: Top Gear Eps. 1 (16) Am Montag, 10.09.2012 um 20:15 Uhr Wehe wenn sie losgelassen: In der neuen Staffel testen die Jungs von "Top Gear" die tollsten Luxuskarossen - manchmal geht´s jedoch auch mit dem Mähdrescher in den Schnee oder dem Hubschrauber aufs Autodach… Die spektakulärsten Autos der Welt, Testfahrten auf dem Vulkan und jede Menge coole Sprüche: DMAX holt "Top Gear" - die Mutter aller Auto-Shows - nach Hause. Das weltweit erfolgreichste TV-Format rund ums Thema „fahrbarer Untersatz“ begeistert seine Zuschauer seit Jahren mit sensationellen Stunts, präzise recherchierten Beiträgen und gefürchteten Kfz-Kritiken. Mehr Leidenschaft fürs Auto geht nicht! Darin ist sich die riesige Fan-Gemeinde des Kult-Formats rund um den Globus einig. Ganz zu schweigen vom bissigen britischen Humor der Moderatoren Jeremy Clarkson, Richard Hammond und James May. Die ironischen Kommentare der Auto-Experten sind eben nicht zu toppen. Kurzum: Top Gear ist Kult! Know-how, Enthusiasmus und Faszination - die preisgekrönte BBC-Produktion hat mit DMAX in Deutschland die perfekte Heimat gefunden. "Als würde die Queen einen Tanga unterm Rock tragen!" - die Vergleiche, die Jeremy Clarkson in dieser Episode zieht, grenzen an Majestätsbeleidung. Doch der Top Gear-Experte ist vom schicken Interieur des Jaguar XJ so begeistert, dass er etwas über die Stränge schlägt. Da die luxuriöse V8- Raubkatze außerdem mächtig Dampf unterm Kessel hat, macht es Jeremy einen Riesenspaß auf der britischen Insel von Küste zu Küste zu brettern. Weitere Highlights dieser Episode: Porsche 959 und Ferrari F40 im Vergleich, sowie ein 3,5 Millionen Euro teuer NASA-Mondbuggy. -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

Are You Thinking of Selling Or Buying?

Are you thinking of Selling or Buying? ACF is the leading International Investment Bank, specialising in selling, buying, fundraising and pre/post deal services for businesses in media and entertainment. Our team of market leading industry experts have advised on more than 90 transactions in the TV Production and Distribution sector with a combined transaction value of over $5 billion. A selection of our deals Greenbird Litton Pilgrim Studios Leftfield Neal Street Media Entertainment Entertainment Productions Sale to Keshet International Sale to Hearst Sale to ITV plc Sale to All3Media ACF acted as Investment ACF acted as ACF acted as ACF acted as ACF acted as Banker to Greenbird Media Investment Banker to Investment Banker to Investment Banker to Investment Banker to Litton Entertainment Pilgrim Studios Leftfield Entertainment Neal Street Productions Left Bank Left Right Paddington and Magical Elves Love Pictures Company Productions Sale to Sony Pictures Sale of Intellectual Property Television Sale to Red Arrow Rights to Studiocanal Sale to the Tinopolis Group Sale to Sky ACF acted as ACF acted as ACF acted as Investment ACF acted as Investment ACF acted as Investment Banker to Investment Banker to Banker to Paddington Banker to Magical Elves Investment Banker to Left Bank Pictures Left/Right and Company Love Productions Mammoth Screen Orion A. Smith & Co New Pictures Top Gear Productions Entertainment Productions Sale to ITV plc Sale to Red Arrow Sale to the Tinopolis Group Sale to All3Media Sale to BBC Worldwide ACF acted as Investment ACF acted as ACF acted as Investment ACF acted as ACF acted as Investment Banker to Mammoth Investment Banker to Banker to A. -

Al Via La 25A Stagione Di Top Gear Con Matt Leblanc, Chris Harris, Rory

VENERDì 10 MAGGIO 2019 Da lunedì 13 maggio alle 21.30 su Spike (canale 49 del dtt), arriva in prima tv assoluta la 25a stagione di Top Gear, il più famoso CarShow della Tv. Al via la 25a stagione di Top Gear con Matt Leblanc, Chris Harris, Rory Reyd e The Stig Il mondo della auto, e tutto ciò che si muove a motore, raccontato con una buona dose di humor tipicamente british e una parte di sana irriverenza: Top Gear è uno dei programmi più longevi della televisione, Da lunedì 13 maggio a partire dalle 21.30 su una pietra miliare dell'intrattenimento automobilistico. Prodotto per SPIKE oltre 20 anni dalla BBC, ha raccolto enorme successo nelle televisioni di tutto il mondo. CRISTIAN PEDRAZZINI Ogni lunedì saranno trasmessi due nuovi episodi della serie che vede protagonisti Matt LeBlanc, celebre per la sua interpretazione di Joey Tribbiani nella popolare sitcom Friends della NBC, Chris Harris firma prestigiosa di molte riviste automobilistiche, e Rory Reid, presentatore televisivo specializzato in motori e tecnologia. I tre conduttori daranno [email protected] vita a sfide originali e entusiasmanti alle quali Top Gear ci ha abituato. SPETTACOLINEWS.IT Immancabile la presenza di The Stig che nel corso della stagione metterà alla frusta bolidi come la McLaren 720S, la Ferrari 812 Superfast, la Chevrolet Camaro e la Alpine A110. Nel primo episodio della serie LeBlanc, Harris e Reid andranno nello Utah, per celebrare il 116° anniversario del V8. Qui testeranno delle nuove macchine che montano questo tipo di motore: LeBlanc guiderà una Ford Shelby Mustang GT350R, Reid una Jaguar F-Type SVR e Harris la McLaren 570GT.