REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: DIPSADIDAE Cubophis Vudii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uromacer Catesbyi (Schlegel) 1. Uromacer Catesbyi Catesbyi Schlegel 2. Uromacer Catesbyi Cereolineatus Schwartz 3. Uromacer Cate

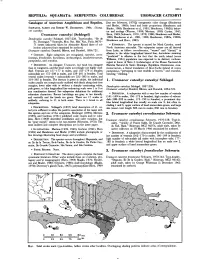

T 356.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE UROMACER CATESBYI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. [but see Schwartz,' 1970]); ontogenetic color change (Henderson and Binder, 1980); head and body proportions (Henderson and SCHWARTZ,ALBERTANDROBERTW. HENDERSON.1984. Uroma• Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981; Henderson, 1982b); behav• cer catesbyi. ior and ecology (Werner, 1909; Mertens, 1939; Curtiss, 1947; Uromacer catesbyi (Schlegel) Horn, 1969; Schwartz, 1970, 1979, 1980; Henderson and Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981, 1982; Henderson, 1982a, 1982b; Dendrophis catesbyi Schlegel, 1837:226. Type-locality, "lie de Henderson and Horn, 1983). St.- Domingue." Syntypes, Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat., Paris, 8670• 71 (sexes unknown) taken by Alexandre Ricord (date of col• • ETYMOLOGY.The species is named for Mark Catesby, noted lection unknown) (not examined by authors). North American naturalist. The subspecies names are all derived Uromacer catesbyi: Dumeril, Bibron, and Dumeril, 1854:72l. from Latin, as follow: cereolineatus, "waxen" and "thread," in allusion to the white longitudinal lateral line; hariolatus meaning • CONTENT.Eight subspecies are recognized, catesbyi, cereo• "predicted" in allusion to the fact that the north island (sensu lineatus,frondicolor, hariolatus, inchausteguii, insulaevaccarum, Williams, 1961) population was expected to be distinct; inchaus• pampineus, and scandax. teguii in honor of Sixto J. Inchaustegui, of the Museo Nacional de • DEFINITION.An elongate Uromacer, but head less elongate Historia Natural de Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana; insu• than in congeners, and the head scales accordingly not highly mod• laevaccarum, a literal translation of lIe-a-Vache (island of cows), ified. Ventrals are 157-177 in males, and 155-179 in females; pampineus, "pertaining to vine tendrils or leaves;" and scandax, subcaudals are 172-208 in males, and 159-201 in females. -

Other Contributions

Other Contributions NATURE NOTES Amphibia: Caudata Ambystoma ordinarium. Predation by a Black-necked Gartersnake (Thamnophis cyrtopsis). The Michoacán Stream Salamander (Ambystoma ordinarium) is a facultatively paedomorphic ambystomatid species. Paedomorphic adults and larvae are found in montane streams, while metamorphic adults are terrestrial, remaining near natal streams (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). Streams inhabited by this species are immersed in pine, pine-oak, and fir for- ests in the central part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Luna-Vega et al., 2007). All known localities where A. ordinarium has been recorded are situated between the vicinity of Lake Patzcuaro in the north-central portion of the state of Michoacan and Tianguistenco in the western part of the state of México (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). This species is considered Endangered by the IUCN (IUCN, 2015), is protected by the government of Mexico, under the category Pr (special protection) (AmphibiaWeb; accessed 1April 2016), and Wilson et al. (2013) scored it at the upper end of the medium vulnerability level. Data available on the life history and biology of A. ordinarium is restricted to the species description (Taylor, 1940), distribution (Shaffer, 1984; Anderson and Worthington, 1971), diet composition (Alvarado-Díaz et al., 2002), phylogeny (Weisrock et al., 2006) and the effect of habitat quality on diet diversity (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). We did not find predation records on this species in the literature, and in this note we present information on a predation attack on an adult neotenic A. ordinarium by a Thamnophis cyrtopsis. On 13 July 2010 at 1300 h, while conducting an ecological study of A. -

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Kansas Biological Survey Report #151 Kelly Kindscher, Randy Jennings, William Norris, and Roland Shook September 8, 2008 Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Cover Photo: The Gila River in New Mexico. Photo by Kelly Kindscher, September 2006. Kelly Kindscher, Associate Scientist, Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, 2101 Constant Avenue, Lawrence, KS 66047, Email: [email protected] Randy Jennings, Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] William Norris, Associate Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Roland Shook, Emeritus Professor, Biology, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Citation: Kindscher, K., R. Jennings, W. Norris, and R. Shook. Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico. Open-File Report No. 151. Kansas Biological Survey, Lawrence, KS. ii + 42 pp. Abstract During 2006 and 2007 our research crews collected data on plants, vegetation, birds, reptiles, and amphibians at 49 sites along the Gila River in southwest New Mexico from upstream of the Gila Cliff Dwellings on the Middle and West Forks of the Gila to sites below the town of Red Rock, New Mexico. -

Epicrates Maurus (Rainbow Boa Or Velvet Mapepire)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Epicrates maurus (Rainbow Boa or Velvet Mapepire) Family: Boidae (Boas and Pythons) Order: Squamata (Lizards and Snakes) Class: Reptilia (Reptiles) Fig. 1. Rainbow boa, Epicrates maurus. [http://squamates.blogspot.com/2010/10/declines-in-snake-and-lizard.html, Downloaded 10 November, 2011] . TRAITS. The rainbow boa, also known as the velvet mapepire, is a snake that grows to a maximum length of 4 feet in males and 4.5 to 5 feet in females. The life span of this species of snake is an average of 20 years if held in captivity and 10 years in the wild. Their name, rainbow boa, originated from their appearance because of an iridescent shine emanating from microscopic ridges on their scales that refract light to produce all the colours of the rainbow. These boas are generally brownish red in colour associated with dark marking during their juvenile life, however this coloration becomes subdued as they get older (Underwood 2009). These snakes are mainly nocturnal and also terrestrial, they have a small head with a narrow neck and a thick body (Boos 2001). Boas are considered primitive snakes and this is supported by the presence of two vestigal, hind limbs which appers as spurs on either side of the cloaca (Conrad 2009). ECOLOGY. Rainbow boas occupy a variety of habitats in Trinidad and Tobago, they can be found in dry tropical forest, rainforest clearings or even close to human settlements such as agricultural communities. Like all boas, they are excellent swimmers, however they restrain from being in contact with water as much as possible. -

Zootaxa, Molecular Phylogeny, Classification, and Biogeography Of

Zootaxa 2067: 1–28 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of West Indian racer snakes of the Tribe Alsophiini (Squamata, Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) S. BLAIR HEDGES1, ARNAUD COULOUX2, & NICOLAS VIDAL3,4 1Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Lab, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Genoscope. Centre National de Séquençage, 2 rue Gaston Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France www.genoscope.fr 3UMR 7138, Département Systématique et Evolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 4Corresponding author. E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Most West Indian snakes of the family Dipsadidae belong to the Subfamily Xenodontinae and Tribe Alsophiini. As recognized here, alsophiine snakes are exclusively West Indian and comprise 43 species distributed throughout the region. These snakes are slender and typically fast-moving (active foraging), diurnal species often called racers. For the last four decades, their classification into six genera was based on a study utilizing hemipenial and external morphology and which concluded that their biogeographic history involved multiple colonizations from the mainland. Although subsequent studies have mostly disagreed with that phylogeny and taxonomy, no major changes in the classification have been proposed until now. Here we present a DNA sequence analysis of five mitochondrial genes and one nuclear gene in 35 species and subspecies of alsophiines. Our results are more consistent with geography than previous classifications based on morphology, and support a reclassification of the species of alsophiines into seven named and three new genera: Alsophis Fitzinger (Lesser Antilles), Arrhyton Günther (Cuba), Borikenophis Hedges & Vidal gen. -

Epicrates Inornatus)Ina Hurricane Impacted Forest1

BIOTROPICA 36(4): 555±571 2004 Spatial Ecology of Puerto Rican Boas (Epicrates inornatus)ina Hurricane Impacted Forest1 Joseph M. Wunderle Jr. 2, Javier E. Mercado International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, P.O. Box 490, Palmer, Puerto Rico 00721, U.S.A. Bernard Parresol Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 200 Weaver Blvd., P.O. Box 2680, Asheville, North Carolina 28802, U.S.A. and Esteban Terranova International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, P.O. Box 490, Palmer, Puerto Rico 00721, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Spatial ecology of Puerto Rican boas (Epicrates inornatus, Boidae) was studied with radiotelemetry in a subtropical wet forest recovering from a major hurricane (7±9 yr previous) when Hurricane Georges struck. Different boas were studied during three periods relative to Hurricane Georges: before only; before and after; and after only. Mean daily movement per month increased throughout the three periods, indicating that the boas moved more after the storm than before. Radio-tagged boas also became more visible to observers after the hurricane. Throughout the three periods, the sexes differed in movements, with males moving greater distances per move and moving more frequently than females. Males showed a bimodal peak of movement during April and June in contrast to the females' July peak. Sexes did not differ in annual home range size, which had a median value of 8.5 ha (range 5 2.0±105.5 ha, N 5 18) for 95 percent adaptive kernal. Females spent more time on or below ground than did males, which were mostly arboreal. -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service 2012 Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae) Christina A. Olson Utah State University, [email protected] Karen H. Beard Utah State University, [email protected] William C. Pitt National Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Olson, Christina A.; Beard, Karen H.; and Pitt, William C., "Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae)" (2012). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 1174. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/1174 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae)1 Christina A. Olson,2 Karen H. Beard,2,4 and William C. Pitt 3 Abstract: The greenhouse frog, Eleutherodactylus planirostris, is a direct- developing (i.e., no aquatic stage) frog native to Cuba and the Bahamas. It was introduced to Hawai‘i via nursery plants in the early 1990s and then subsequently from Hawai‘i to Guam in 2003. The greenhouse frog is now widespread on five Hawaiian Islands and Guam. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

Species Selection Process

FINAL Appendix J to S Volume 3, Book 2 JULY 2008 COYOTE SPRINGS INVESTMENT PLANNED DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FINAL VOLUME 3 Coyote Springs Investment Planned Development Project Appendix J to S July 2008 Prepared EIS for: LEAD AGENCY U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Reno, NV COOPERATING AGENCIES U.S. Army Corps of Engineers St. George, UT U.S. Bureau of Land Management Ely, NV Prepared MSHCP for: Coyote Springs Investment LLC 6600 North Wingfield Parkway Sparks, NV 89496 Prepared by: ENTRIX, Inc. 2300 Clayton Road, Suite 200 Concord, CA 94520 Huffman-Broadway Group 828 Mission Avenue San Rafael, CA 94901 Resource Concepts, Inc. 340 North Minnesota Street Carson City, NV 89703 PROJECT NO. 3132201 COYOTE SPRINGS INVESTMENT PLANNED DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Appendix J to S ENTRIX, Inc. Huffman-Broadway Group Resource Concepts, Inc. 2300 Clayton Road, Suite 200 828 Mission Avenue 340 North Minnesota Street Concord, CA 94520 San Rafael, CA 94901 Carson City, NV 89703 Phone 925.935.9920 Fax 925.935.5368 Phone 415.925.2000 Fax 415.925.2006 Phone 775.883.1600 Fax 775.883.1656 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix J Mitigation Plan, The Coyote Springs Development Project, Lincoln County, Nevada Appendix K Summary of Nevada Water Law and its Administration Appendix L Alternate Sites and Scenarios Appendix M Section 106 and Tribal Consultation Documents Appendix N Fiscal Impact Analysis Appendix O Executive Summary of Master Traffic Study for Clark County Development Appendix P Applicant for Clean Water Act Section 404 Permit Application, Coyote Springs Project, Lincoln County, Nevada Appendix Q Response to Comments on the Draft EIS Appendix R Agreement for Settlement of all Claims to Groundwater in the Coyote Spring Basin Appendix S Species Selection Process JULY 2008 FINAL i APPENDIX S Species Selection Process Table of Contents Appendix S: Species Selection Process ........................................................................................................ -

Biological and Proteomic Analysis of Venom from the Puerto Rican Racer (Alsophis Portoricensis: Dipsadidae)

Toxicon 55 (2010) 558–569 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Toxicon journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/toxicon Biological and proteomic analysis of venom from the Puerto Rican Racer (Alsophis portoricensis: Dipsadidae) Caroline L. Weldon, Stephen P. Mackessy* School of Biological Sciences, University of Northern Colorado, 501 20th Street, CB 92, Greeley, CO 80639-0017, USA article info abstract Article history: The Puerto Rican Racer Alsophis portoricensis is known to use venom to subdue lizard prey, Received 12 August 2009 and extensive damage to specific lizard body tissues has been well documented. The Received in revised form toxicity and biochemistry of the venom, however, has not been explored extensively. We 27 September 2009 employed biological assays and proteomic techniques to characterize venom from Accepted 2 October 2009 A. portoricensis anegadae collected from Guana Island, British Virgin Islands. High metal- Available online 14 October 2009 loproteinase and gelatinase, as well as low acetylcholinesterase and phosphodiesterase activities were detected, and the venom hydrolyzed the a-subunit of human fibrinogen Keywords: Biological roles very rapidly. SDS-PAGE analysis of venoms revealed up to 22 protein bands, with masses of w Colubrid 5–160 kDa; very little variation among individual snakes or within one snake between CRISP venom extractions was observed. Most bands were approximately 25–62 kD, but MALDI- Enzymes TOF analysis of crude venom indicated considerable complexity in the 1.5–13 kD mass a-Fibrinogenase range, including low intensity peaks in the 6.2–8.8 kD mass range (potential three-finger Gland histology toxins). MALDI-TOF/TOF MS analysis of tryptic peptides confirmed that a 25 kDa band was Hemorrhage a venom cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRiSP) with sequence homology with tigrin, Mass spectrometry a CRiSP from the natricine colubrid Rhabdophis tigrinus. -

YSF 2020-PROGRAMME-1.Pdf

YOUNG SYSTEMATISTS' FORUM Day 1 Monday 23rd November 2020, Zoom [all timings are GMT+0] 11.50 Opening remarks David Williams, President of the Systematics Association 12.00 Rodrigo Vargas Pêgas Species Concepts and the Anagenetic Process Importance on Evolutionary History 12.15 Katherine Odanaka Insights into the phylogeny and biogeography of the cleptoparasitic bee genus Nomada 12.30 Minette Havenga Association among global populations of the Eucalyptus foliar pathogen Teratosphaeria destructans 12.45 David A. Velasquez-Trujillo Phylogenetic relationships of the whiptail lizards of the genus Holcosus COPE 1862 (Squamata: Teiidae) based on morphological and molecular evidence 13.00 Break 10 minutes 13.10 Arsham Nejad Kourki The Ediacaran Dickinsonia is a stem-eumetazoan 13.25 Flávia F.Petean The role of the American continent on the diversification of the stingrays’ genus Hypanus Rafinesque, 1818 (Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae) 13.40 Peter M.Schächinger Discovering species diversity in Antarctic marine slugs (Mollusca: Gastropoda) 13.55 Alison Irwin Eight new mitogenomes clarify the phylogenetic relationships of Stromboidea within the gastropod phylogenetic framework 14.10 Break 20 minutes 14.30 Érica Martinha Silva de The lineages of foliage-roosting fruit bat Uroderma spp. (Chiroptera: Souza Phyllostomidae 14.45 Melissa Betters Rethinking Informative Traits: Environmental Influence on Shell Morphology in Deep-Sea Gastropods 15.00 J. Renato Morales-Mérida- New lineages of Holcosus undulatus (Squamata: Teiidae) in Guatemala 15.15 Roberto