Transposition Primer.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

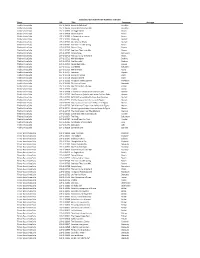

Finale Transposition Chart, by Makemusic User Forum Member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans

Finale Transposition Chart, by MakeMusic user forum member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans. Sounding Written Inter- Key Usage (Some Common Western Instruments) val Alter C Up 2 octaves Down 2 octaves -14 0 Glockenspiel D¯ Up min. 9th Down min. 9th -8 5 D¯ Piccolo C* Up octave Down octave -7 0 Piccolo, Celesta, Xylophone, Handbells B¯ Up min. 7th Down min. 7th -6 2 B¯ Piccolo Trumpet, Soprillo Sax A Up maj. 6th Down maj. 6th -5 -3 A Piccolo Trumpet A¯ Up min. 6th Down min. 6th -5 4 A¯ Clarinet F Up perf. 4th Down perf. 4th -3 1 F Trumpet E Up maj. 3rd Down maj. 3rd -2 -4 E Trumpet E¯* Up min. 3rd Down min. 3rd -2 3 E¯ Clarinet, E¯ Flute, E¯ Trumpet, Soprano Cornet, Sopranino Sax D Up maj. 2nd Down maj. 2nd -1 -2 D Clarinet, D Trumpet D¯ Up min. 2nd Down min. 2nd -1 5 D¯ Flute C Unison Unison 0 0 Concert pitch, Horn in C alto B Down min. 2nd Up min. 2nd 1 -5 Horn in B (natural) alto, B Trumpet B¯* Down maj. 2nd Up maj. 2nd 1 2 B¯ Clarinet, B¯ Trumpet, Soprano Sax, Horn in B¯ alto, Flugelhorn A* Down min. 3rd Up min. 3rd 2 -3 A Clarinet, Horn in A, Oboe d’Amore A¯ Down maj. 3rd Up maj. 3rd 2 4 Horn in A¯ G* Down perf. 4th Up perf. 4th 3 -1 Horn in G, Alto Flute G¯ Down aug. 4th Up aug. 4th 3 6 Horn in G¯ F# Down dim. -

Ron Mcclure • Harris Eisenstadt • Sackville • Event Calendar

NEW YORK FebruaryVANGUARD 2010 | No. 94 Your FREE Monthly JAZZ Guide to the New ORCHESTRA York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com a band in the vanguard Ron McClure • Harris Eisenstadt • Sackville • Event Calendar NEW YORK We have settled quite nicely into that post-new-year, post-new-decade, post- winter-jazz-festival frenzy hibernation that comes so easily during a cold New York City winter. It’s easy to stay home, waiting for spring and baseball and New York@Night promising to go out once it gets warm. 4 But now is not the time for complacency. There are countless musicians in our fair city that need your support, especially when lethargy seems so appealing. To Interview: Ron McClure quote our Megaphone this month, written by pianist Steve Colson, music is meant 6 by Donald Elfman to help people “reclaim their intellectual and emotional lives.” And that is not hard to do in a city like New York, which even in the dead of winter, gives jazz Artist Feature: Harris Eisenstadt lovers so many choices. Where else can you stroll into the Village Vanguard 7 by Clifford Allen (Happy 75th Anniversary!) every Monday and hear a band with as much history as the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra (On the Cover). Or see as well-traveled a bassist as On The Cover: Vanguard Jazz Orchestra Ron McClure (Interview) take part in the reunion of the legendary Lookout Farm 9 by George Kanzler quartet at Birdland? How about supporting those young, vibrant artists like Encore: Lest We Forget: drummer Harris Eisenstadt (Artist Feature) whose bands and music keep jazz relevant and exciting? 10 Svend Asmussen Joe Maneri In addition to the above, this month includes a Lest We Forget on the late by Ken Dryden by Clifford Allen saxophonist Joe Maneri, honored this month with a tribute concert at the Irondale Center in Brooklyn. -

Flute Oboe Clarinet Basson Saxophone Trumpet French Horn

PROGRAM ECMS High School Wind Ensemble Personnel Tribute to Grainger, arr. Ragsdale Percy Aldridge Grainger Flute Trombone Andrew Bronco arr. Chalon Ragsdale Mary Ehrlinger Zachary Canning I. Country Gardens Alena Scott Tyler Dawe II. My Dark-Haired Maid Camryn Wlostowski III. The Gypsy’s Wedding Day Shaun Fitzgerald Justin Karnisky Oboe Michael McKenzie Claire Houston Aidan Ross Concertino Cécile Chaminade Samuel Stringer ed. Wilkins Alena Scott, flute soloist Clarinet Euphonium Sean Devlin Melissa Cannan Cole Karnisky Greg Lewandowski Peter Odhiambo Chuck Linn Graham His Yu Justyn Loney-Newman Jupiter Hymn Gustav Holst Rainna Frombgen arr. Lindsay Bronnenkant Tuba Lindsay Bronnenkant, conductor Basson Ziv Rapoport Briana Rafferty Ethan Smith Henry Stringer String Bass Saint and the City Jacob de Haan Saxophone Samuel Bowley Isabel Goldstein Samantha Kotz Gabriel Williams Percussion Cameron Connioto Angels Will Come Quincy Hilliard Trumpet Jared Emerson Evan Preston Tyler Hancock Felix Schneider Gabriel Foster Moving at the Speed of Sound Mark Lortz Wu Ryu Sean Watson French Horn Russian Sailors Dance Reinhold Glière Angelique Brewington arr. Anthony Susi SUMMER@EASTMAN June 20 – August 28, 2021 Join us for another summer of exceptional music making at Eastman, with special guest artists, Community Music School and collegiate faculty, and Summer Session program participants! Events are either free and open to the public or ticketed. Tickets are $10 (free for U/R or student ID holders) and are available at the door one hour before the concert start time. For more information about Summer@Eastman, please visit: www.esm.rochester.edu/summer ECMS High School Wind Ensemble Participant Concert July 23, 2021 11:00 a.m. -

The Rise and Fall of the Bass Clarinet in a the RISE and FALL of the BASS CLARINET in A

Keith Bowen - The rise and fall of the bass clarinet in A THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BASS CLARINET IN A Keith Bowen The bass clarinet in A was introduced by Wagner in Lohengrin in 1848. Unlike the bass instruments in C and Bb, it is not known to have a history in wind bands. Its appearance was not, so far as is known, accompanied by any negotiations with makers. Over the next century, it was called for by over twenty other composers in over sixty works. The last works to use the bass in A are, I believe, Strauss’ Sonatine für Blaser, 1942, and Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie (1948, revised 1990) and Gunther Schuller’s Duo Sonata (1949) for clarinet and bass clarinet. The instrument has all but disappeared from orchestral use and there are very few left in the world. It is now often called obsolete, despite the historically-informed performance movement over the last half century which emphasizes, inter alia, performance on the instruments originally specified by the composer. And the instrument has been largely neglected by scholars. Leeson1 drew attention to the one-time popularity and current neglect of the instrument, in an article that inspired the current study, and Joppig2 has disussed the use of the various tonalities of clarinet, including the bass in A, by Gustav Mahler. He pointed out that the use of both A and Bb clarinets in both soprano and bass registers was absolutely normal in Mahler’s time, citing Heinrich Schenker writing as Artur Niloff in 19083. Otherwise it has been as neglected in the literature as it is in the orchestra. -

Instruments of the Orchestra

INSTRUMENTS OF THE ORCHESTRA String Family WHAT: Wooden, hollow-bodied instruments strung with metal strings across a bridge. WHERE: Find this family in the front of the orchestra and along the right side. HOW: Sound is produced by a vibrating string that is bowed with a bow made of horse tail hair. The air then resonates in the hollow body. Other playing techniques include pizzicato (plucking the strings), col legno (playing with the wooden part of the bow), and double-stopping (bowing two strings at once). WHY: Composers use these instruments for their singing quality and depth of sound. HOW MANY: There are four sizes of stringed instruments: violin, viola, cello and bass. A total of forty-four are used in full orchestras. The string family is the largest family in the orchestra, accounting for over half of the total number of musicians on stage. The string instruments all have carved, hollow, wooden bodies with four strings running from top to bottom. The instruments have basically the same shape but vary in size, from the smaller VIOLINS and VIOLAS, which are played by being held firmly under the chin and either bowed or plucked, to the larger CELLOS and BASSES, which stand on the floor, supported by a long rod called an end pin. The cello is always played in a seated position, while the bass is so large that a musician must stand or sit on a very high stool in order to play it. These stringed instruments developed from an older instrument called the viol, which had six strings. -

Clarinet Quarter-Tone Fingering Chart

Clarinet Quarter-Tone Fingering Chart 1st Edition rev.1 2017 Jason Alder www.jasonalder.com ii Author’s Note This clarinet quarter-tone fingering chart developed as a continuation of my initial work of one for bass clarinet, which grew from my extensive playing of contemporary music and study of South-Indian Karnatic music. My focus had been primarily on bass clarinet, so the development of this chart for soprano clarinet didn’t come to realization until some years later as my own need for it arose, occurring simultaneously with a decision to rework the initial bass clarinet chart into a second edition. The first edition for clarinet therefore follows the same conventions as the second edition bass clarinet fingering chart. This first revision revisits a few quarter-tone fingerings around the “break” after I discovered some better ones to use. Jason Alder London, 2017 iii Guide to the Fingering Chart This fingering chart was made using a Buffet R13 clarinet, and thus the fingerings notated are based on the Boehm system. Because some differences may exist between different manufacturers, it is important to note how this system correlates to your own instrument. In some fingerings I have used the Left Hand Ab//Eb key, which not all instruments have. I’ve included this only when its use is an option, but have omitted the outline when it’s not. Many notes, particularly quarter-tones and altissimo notes, can have different fingerings. I have notated what I found to be best in tune for me, with less regard for ease and fluidity of playing. -

Preliminary Results Clarinet, Flute, Horn, Soprano Singer, Trumpet

Performing Arts Aerosol Study Round one preliminary results Clarinet, Flute, Horn, Soprano Singer, Trumpet Study Chairs James Weaver - NFHS Director of Mark Spede – CBDNA President, Performing Arts and Sports Director of Bands, Clemson University Lead Funders Contributing Organizations Supporting Organizations American School Band Directors Association (ASBDA) International Music Council American String Teachers Association (ASTA) International Society for Music Education Arts Education in Maryland Schools (AEMS) League of American Orchestras Association Européenne des Conservatoires/Académies de Louisiana Music Educators Association Musique et Musikhochschulen (AEC) (LMEA) Buffet et Crampon MidWest Clinic Bundesverband der deutschen Minority Band Directors National Association Musikinstrumentenhersteller e.V Music Industries Association Chicago Children's Choir Musical America Worldwide Children's Chorus of Washington National Dance Education Organization Chorus America (NDEO) Confederation of European Music Industries (CAFIM) National Flute Association (NFA) Drum Corps International (DCI) National Guild for Community Arts Education Educational Theatre Association (EdTA) National Music Council of the US European Choral Association - Europa Cantat Percussive Arts Society (PAS) HBCU National Band Directors' Consortium Save the Music Foundation High School Directors National Association (HSBDNA) WGI Sport of the Arts International Conductors Guild Lead Researchers Dr. Shelly Miller Dr. Jelena Srebric University of Colorado Boulder University -

Bid Awarded Item List

Bid Awarded Item List 1810 2018-2019 Music Bid Commodity Unit of Awarded Extended Code Description Vendor Measure Price Qty Price 18000010 Drum Heads: 16" MS1 White Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD16MS1W 233310-STEVE WEISS MUSIC EACH $21.31 1 $21.31 18000015 Drum Heads: 16" MX1 Black Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD16MX1BDH34516B 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC EACH $30.24 1 $30.24 18000020 Drum Heads: 16" MX1 White Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD16MX1WDH34516 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC EACH $26.94 1 $26.94 18000025 Drum Heads: 18" MS1 White Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD18MS1WDH52118 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC EACH $21.74 1 $21.74 18000030 Drum Heads: 18" MX1 Black Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD18MX1BDH34518B 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC EACH $32.24 1 $32.24 18000035 Drum Heads: 18" MX1 White Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD18MX1WDH34518 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC EACH $28.94 1 $28.94 18000040 Drum Heads: 20" MS1 White Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD20MS1WDH52120 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC EACH $23.24 1 $23.24 18000045 Drum Heads: 20" MX1 Black Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD20MX1BDH34520B 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC EACH $33.94 1 $33.94 18000050 Drum Heads: 20" MX1 White Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD20MX1WDH34520 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC EACH $30.94 1 $30.94 18000055 Drum Heads: 22" MS1 White Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD22MS1WDH52122 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC EACH $25.44 1 $25.44 18000060 Drum Heads: 22" MX1 Black Bass, Evans, No substitutions BD22MX1BDH34522B 123468-CASCIO INTERSTATE MUSIC -

Copy of 2017 Solo & Ensemble Additions

2016/2017 Solo & Ensemble Additions and Edits Event UIL Title Composer Arranger Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32691 Sweet Suffolk Owl Hundley Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32693 Come Ready and See Me Hundley Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32696 Ich Sagte Nicht Beach Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32698 Deine Blumen Beach Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32700 Je Demande a l'oiseau Beach Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32701 Warnung Mozart Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32702 Als Luisa die Briefe Mozart Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32704 The Year's at the Spring Beach Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32705 Pippa's Song Rorem Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32707 See How They LoVe Me Rorem Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32709 Simple Song Bernstein Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32711 The Lord is my Shepherd Childs Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32712 Wir Wandelten Brahms Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32713 Die Mainacht Brahms Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32714 Susses Begrabnis Loewe Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32715 Standchen Schubert Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32716 Notre Amour Faure Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32717 Lamento Duparc Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32718 OuVre ton Coeur Bizet Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32719 Chanson d'AVril Bizet Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32721 Ho Sparse Tante Lagrime Morlacchi Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32723 Oh, Vieni al Mare Donizetti Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32725 Non t'accostare all'urnA Ferrari Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32727 L'addio Vaccai Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32728 In Uomini in soldati from Cosi fan tutte Mozart Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32729 Una Donna a Quindici anni from Cosi fan Tutte Mozart Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32730 Batti -

New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon

Hayley Elizabeth Roud 300220780 NZSM596 Supervisor- Professor Donald Maurice Master of Musical Arts Exegesis 10 December 2010 New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon Contents 1 Introduction 3 2.1 History of the contrabassoon in the international context 3 Development of the instrument 3 Contrabassoonists 9 2.2 History of the contrabassoon in the New Zealand context 10 3 Selected New Zealand repertoire 16 Composers: 3.1 Bryony Jagger 16 3.2 Michael Norris 20 3.3 Chris Adams 26 3.4 Tristan Carter 31 3.5 Natalie Matias 35 4 Summary 38 Appendix A 39 Appendix B 45 Appendix C 47 Appendix D 54 Glossary 55 Bibliography 68 Hayley Roud, 300220780, New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon, 2010 3 Introduction The contrabassoon is seldom thought of as a solo instrument. Throughout the long history of contra- register double-reed instruments the assumed role has been to provide a foundation for the wind chord, along the same line as the double bass does for the strings. Due to the scale of these instruments - close to six metres in acoustic length, to reach the subcontra B flat’’, an octave below the bassoon’s lowest note, B flat’ - they have always been difficult and expensive to build, difficult to play, and often unsatisfactory in evenness of scale and dynamic range, and thus instruments and performers are relatively rare. Given this bleak outlook it is unusual to find a number of works written for solo contrabassoon by New Zealand composers. This exegesis considers the development of contra-register double-reed instruments both internationally and within New Zealand, and studies five works by New Zealand composers for solo contrabassoon, illuminating what it was that led them to compose for an instrument that has been described as the 'step-child' or 'Cinderella' of both the wind chord and instrument makers. -

Instrument Descriptions

RENAISSANCE INSTRUMENTS Shawm and Bagpipes The shawm is a member of a double reed tradition traceable back to ancient Egypt and prominent in many cultures (the Turkish zurna, Chinese so- na, Javanese sruni, Hindu shehnai). In Europe it was combined with brass instruments to form the principal ensemble of the wind band in the 15th and 16th centuries and gave rise in the 1660’s to the Baroque oboe. The reed of the shawm is manipulated directly by the player’s lips, allowing an extended range. The concept of inserting a reed into an airtight bag above a simple pipe is an old one, used in ancient Sumeria and Greece, and found in almost every culture. The bag acts as a reservoir for air, allowing for continuous sound. Many civic and court wind bands of the 15th and early 16th centuries include listings for bagpipes, but later they became the provenance of peasants, used for dances and festivities. Dulcian The dulcian, or bajón, as it was known in Spain, was developed somewhere in the second quarter of the 16th century, an attempt to create a bass reed instrument with a wide range but without the length of a bass shawm. This was accomplished by drilling a bore that doubled back on itself in the same piece of wood, producing an instrument effectively twice as long as the piece of wood that housed it and resulting in a sweeter and softer sound with greater dynamic flexibility. The dulcian provided the bass for brass and reed ensembles throughout its existence. During the 17th century, it became an important solo and continuo instrument and was played into the early 18th century, alongside the jointed bassoon which eventually displaced it. -

![2014 TSHB Recording & Audition Procedures[2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4723/2014-tshb-recording-audition-procedures-2-794723.webp)

2014 TSHB Recording & Audition Procedures[2]

WSU / Tri-State Honor Band AUDITION RECORDING PROCEDURES IMPORTANT: TO AVOID DISQUALIFICATION FOLLOW THESE INSTRUCTIONS EXACTLY • Audition recordings can be submitted ONE of two ways: Either upload your audition online (along with your online application), OR mail in your audition recording in compact disc (CD) format. NOTE: DEADLINE: Postmarked or Uploaded Online no later than Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2013 • Only 1 auditioning student per submitted recording (per Online Upload or mailed-in CD). • If mailing-in, your CD must be in a case. CLEARLY LABEL both the CD disc, and the CD case with your name, instrument, high school, city, and state. • Recordings must be clear, and of high recording quality. Please use only HIGH QUALITY CDs. We cannot “filter through” fuzzy recordings … poorly recorded submissions will be automatically disqualified. Please submit each individual recording according to the following steps: STEP 1: At the beginning of the recording, the student should state his/her name, instrument, high school, city, and state. (Trombonists: Please state whether you play tenor or bass trombone, and whether you have an F-attachment). (Euphonium/Baritone Players: Please state whether you are a treble clef or bass clef reader). STEP 2: The student should perform scales as listed below for their instrument in quarter or eighth notes at a minimum tempo of quarter = 112 mm. Students may choose to perform faster and for more than the minimum octave requirements. Flute – (Indicate if the student also plays piccolo) – C major (three octaves,