Incomplete Resyllabification and Bidirectional Coupling in Spanish 2 Travis G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of a Text to Speech System for Devanagari Konkani

DEVELOPMENT OF A TEXT TO SPEECH SYSTEM FOR DEVANAGARI KONKANI A Thesis submitted to Goa University for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science and Technology By Nilesh B. Fal Dessai GOA UNIVERSITY Taleigao Plateau May 2017 Development of a Text to Speech System for Devanagari Konkani A Thesis submitted to Goa University for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science and Technology By Nilesh B. Fal Dessai GOA UNIVERSITY Taleigao Plateau May 2017 Statement As required under the ordinance OB-9.9 of Goa University, I, Nilesh B. Fal Dessai, state that the present Thesis entitled, ‘Development of a Text to Speech System for Devanagari Konkani’ is my original contribution carried out under the supervision of Dr. Jyoti D. Pawar, Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science and Technology, Goa University and the same has not been submitted on any previous occasion. To the best of my knowledge, the present study is the first comprehensive work of its kind in the area mentioned. The literature related to the problem investigated has been cited. Due acknowledgments have been made whenever facilities and suggestions have been availed of. (Nilesh B. Fal Dessai) i Certificate This is to certify that the thesis entitled ‘Development of a Text to Speech System for Devanagari Konkani’, submitted by Nilesh B. Fal Dessai, for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science and Technology is based on his original studies carried out under my supervision. The thesis or any part thereof has not been previously submitted for any other degree or diploma in any University or Institute. -

The Conductor Model of Online Speech Modulation

The Conductor Model of Online Speech Modulation Fred Cummins Department of Computer Science, University College Dublin [email protected] Abstract. Two observations about prosodic modulation are made. Firstly, many prosodic parameters co-vary when speaking style is altered, and a similar set of variables are affected in particular dysarthrias. Second, there is a need to span the gap between the phenomenologically sim- ple space of intentional speech control and the much higher dimensional space of manifest effects. A novel model of speech production, the Con- ductor, is proposed which posits a functional subsystem in speech pro- duction responsible for the sequencing and modulation of relatively in- variant elements. The ways in which the Conductor can modulate these elements are limited, as its domain of variation is hypothesized to be a relatively low-dimensional space. Some known functions of the cortico- striatal circuits are reviewed and are found to be likely candidates for implementation of the Conductor, suggesting that the model may be well grounded in plausible neurophysiology. Other speech production models which consider the role of the basal ganglia are considered, leading to some observations about the inextricable linkage of linguistic and motor elements in speech as actually produced. 1 The Co-Modulation of Some Prosodic Variables It is a remarkable fact that speakers appear to be able to change many aspects of their speech collectively, and others not at all. I focus here on those prosodic variables which are collectively affected by intentional changes to speaking style, and argue that they are governed by a single modulatory process, the ‘Con- ductor’. -

COMMITTEE TRUSTEES: Philip Rubin, Mark Boxer, Sandy Cloud

DRAFT MINUTES SPECIAL TELEPHONE MEETING OF THE COMMITTEE FOR RESEARCH, ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND INNOVATION University of Connecticut Board of Trustees February 15, 2021 COMMITTEE TRUSTEES: Philip Rubin, Mark Boxer, Sandy Cloud, Marilda Gandara ADDITIONAL TRUSTEES: Chairman Toscano COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Rich Vogel, Tim Shannon UNIVERSITY SENATE REP: Jeannette Pritchard STAFF: Joanna Desjardin, President Katsouleas, Radenka Maric, David Nobel, Rachel Rubin, Dan Schwartz, Jeffrey Shoulson, Dan Weiner Committee Vice Chair Rubin convened the meeting at 10:01 a.m. by telephone. No public comment was volunteered on any of the agenda items. On a motion by Trustee Cloud, seconded by Mr. Vogel, the minutes from the November 16, 2020, Special Meeting of the REI Committee were approved. Vice Chair Rubin informed the committee that University Senate Representative Dr. Rajeev Bansal has retired and welcomed Dr. Jeanette Pritchard as the University Senate Representative on the committee. Vice Chair Rubin gave opening remarks and presented the publication, UConn in the Media. If anyone wants a copy they can contact Vice Chair Rubin or Joanna Desjardin. Congratulated Dr. David Noble for a featured article in UConn Today on entrepreneurship. Congratulated Dr. Radenka Maric for becoming a member of AAAS and her publication, Atomistic Insights into the Hydrogen Oxidation Reaction of Palladium-Ceria Bifunctional Catalysts for Anion-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells, which is about her important work she and her colleagues continue to do on fuel cells. Would like to hear more about this at a future meeting. Welcomed Dr. Daniel Weiner, Vice President for Global Affairs, to the meeting. Vice Chair Rubin introduced Dr. Radenka Maric, Vice President for Research, Innovation & Entrepreneurship. -

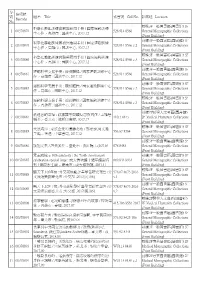

序號no. 條碼號barcode 題名title 索書號call No. 館藏地location 1

序 條碼號 號 題名 Title 索書號 Call No. 館藏地 Location Barcode No. 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 科學化體能訓練實務與應用手冊 / 國家運動訓練 1 00370878 528.914 8566 General Monographic Collections 中心作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 科學化體能訓練實務與應用手冊 / 國家運動訓練 2 00370879 528.914 8566 c.2 General Monographic Collections 中心作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 科學化體能訓練實務與應用手冊 / 國家運動訓練 3 00370880 528.914 8566 c.3 General Monographic Collections 中心作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 運動科學支援手冊 : 競技體操 / 國家運動訓練中心 4 00370881 528.914 8566 General Monographic Collections 作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 運動科學支援手冊 : 競技體操 / 國家運動訓練中心 5 00370882 528.914 8566 c.2 General Monographic Collections 作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 運動科學支援手冊 : 競技體操 / 國家運動訓練中心 6 00370883 528.914 8566 c.3 General Monographic Collections 作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟2F醫學人文專區(圖書館) 被遺忘的幸福 : 敘事醫學閱讀反思與寫作 / 王雅慧 7 00370884 410.3 8443 2F Medical Humanity Collections 編著 .- 臺北市 : 城邦印書館, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 大浪淘沙 : 家族企業的優勝劣敗 / 鄭宏泰,周文港 8 00370885 553.67 8764 General Monographic Collections 主編 .- 香港 : 中華書局, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 9 00370886 旅加文集 / 許業武作 .- 臺北市 : 黃紅梅, 民107.04 078 8483 General Monographic Collections (Front Building) 眾志成城 = 10th solidarity : the Tenth Anniversary 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 10 00370887 celebration special issue : 成大博物館十週年館慶特 069.833 8933 General Monographic Collections 刊 / 陳政宏主編 .- 臺南市 : 成大博物館, 2017.11 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F -

Universidade Do Algarve

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sapientia UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE Quebra de barreiras de comunica»c~aopara portadores de paralisia cerebral. Paulo Alexandre Lucas Afonso Condado Doutoramento em Engenharia Electr¶onicae Computa»c~ao Ci^enciasde Computa»c~ao 2009 UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE Quebra de barreiras de comunica»c~aopara portadores de paralisia cerebral. Paulo Alexandre Lucas Afonso Condado Tese orientada por Professor Fernando Miguel Pais da Gra»caLobo Doutoramento em Engenharia Electr¶onicae Computa»c~ao Ci^enciasde Computa»c~ao 2009 Resumo Nos ¶ultimosanos, o estudo das tecnologias de acessibilidade tem adquirido relev^anciana ¶areade interfaces pessoa-m¶aquina. O desenvolvimento de dis- positivos, m¶etodos, e aplica»c~oesespeci¯camente desenhadas para superar as limita»c~oesdos utilizadores facilita a interac»c~aodestes com o mundo exterior. A import^anciado estudo nesta ¶area¶eenorme, visto facilitar a interac»c~ao dos portadores de de¯ci^enciascom os meios tecnol¶ogicosque, por sua vez, possibilitam-lhes uma melhor comunica»c~aoe interac»c~aocom os outros, con- tribuindo signi¯cativamente para a sua integra»c~aona sociedade. Esta disserta»c~aoapresenta um sistema inovador, conhecido por Easy- Voice, que integra diversas tecnologias para permitir que uma pessoa com de¯ci^enciasna fala possa efectuar chamadas telef¶onicasusando uma voz sintetizada. Subjacente a este sistema, desenhado com o objectivo de dis- ponibilizar um interface acess¶³vel at¶epara utilizadores que possuam graves problemas de coordena»c~aomotora, est¶ao conceito que ¶eposs¶³vel combinar tecnologias j¶aexistentes para criar mecanismos que facilitem a comunica»c~ao dos portadores de de¯ci^enciasa longas dist^ancias,nomeadamente as tecno- logias de s¶³ntese de voz, voz sobre IP (VoIP) e m¶etodos de interac»c~aopara portadores de limita»c~oesmotoras. -

TADA (Task Dynamics Application) Manual

TADA (TAsk Dynamics Application) manual Copyright Haskins Laboratories, Inc., 2001-2006 300 George Street, New Haven, CT 06514, USA written by Hosung Nam ([email protected]), Louis Goldstein ([email protected]) Developers: Catherine Browman, Louis Goldstein, Hosung Nam, Philip Rubin, Michael Proctor, Elliot Saltzman (alphabetical order) Description The core of TADA is a new MATLAB implementation of the Task Dynamic model of inter-articulator coordination in speech (Saltzman & Munhall, 1989). This functional coordination is accomplished with reference to speech Tasks, which are defined in the model as constriction Gestures accomplished by the various vocal tract constricting devices. Constriction formation is modeled using task-level point-attractor dynamical systems that guide the dynamical behavior of individual articulators and their coupling. This implementation includes not only the inter-articulator coordination model, but also • a planning model for inter-gestural timing, based on coupled oscillators (Nam et al, in prog) • a model (GEST) that generates the gestural coupling structure (graph) for an arbitrary English utterance from text input (either orthographic or an ARPABET transcription). Functionality TADA implements three models that are connected to one another as illustrated by the boxes in Figure 1. 1. Syllable structure-based gesture coupling model Takes as input a text string and generates an intergestural coupling graph, that specifies the gestures composing the utterance (represented in terms of tract variable dynamical parameters and articulator weights) and the coupling relations among the gestures’ timing oscillators. 2. Coupled oscillator model of inter-gestural coordination Takes as input a coupling graph, and generates a gestural score, that specifies activation intervals in time for each gesture. -

Voice Synthesizer Application Android

Voice synthesizer application android Continue The Download Now link sends you to the Windows Store, where you can continue the download process. You need to have an active Microsoft account to download the app. This download may not be available in some countries. Results 1 - 10 of 603 Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next See also: Speech Synthesis Receming Device is an artificial production of human speech. The computer system used for this purpose is called a speech computer or speech synthesizer, and can be implemented in software or hardware. The text-to-speech system (TTS) converts the usual text of language into speech; other systems display symbolic linguistic representations, such as phonetic transcriptions in speech. Synthesized speech can be created by concatenating fragments of recorded speech that are stored in the database. Systems vary in size of stored speech blocks; The system that stores phones or diphones provides the greatest range of outputs, but may not have clarity. For specific domain use, storing whole words or suggestions allows for high-quality output. In addition, the synthesizer may include a vocal tract model and other characteristics of the human voice to create a fully synthetic voice output. The quality of the speech synthesizer is judged by its similarity to the human voice and its ability to be understood clearly. The clear text to speech program allows people with visual impairments or reading disabilities to listen to written words on their home computer. Many computer operating systems have included speech synthesizers since the early 1990s. A review of the typical TTS Automatic Announcement System synthetic voice announces the arriving train to Sweden. -

Paper VR2000

VTalk: A System for generating Text-to-Audio-Visual Speech Prem Kalra, Ashish Kapoor and Udit Kumar Goyal Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi Contact email: [email protected] Abstract This paper describes VTalk, a system for synthesizing text-to-audiovisual speech (TTAVS), where the input text is converted into an audiovisual speech stream incorporating the head and eye movements. It is an image-based system, where the face is modeled using a set of images of a human subject. A concatination of visemes –the corresponding lip shapes for phonemes— can be used for modeling visual speech. A smooth transition between visemes is achieved using morphing along the correspondence between the visemes obtained by optical flows. The phonemes and timing parameters given by the text-to-speech synthesizer determines the corresponding visemes to be used for the synthesis of the visual stream. We provide a method using polymorphing to incorporate co-articulation during the speech in our TTAVS. We also include nonverbal mechanisms in visual speech communication such as eye blinks and head nods, which make the talking head model more lifelike. For eye movement, a simple mask based approach is employed and view morphing is used to generate the intermediate images for the movement of head. All these features are integrated into a single system, which takes text, head and eye movement parameters as input and produces the complete audiovisual stream. Keywords: Text-to-audio-visual speech, Morphing, Visemes, Co-articulation. 1. Introduction The visual channel in speech communication is of great importance, a view of a face can improve intelligibility of both natural and synthetic speech. -

Sine-Wave Synthesis, Or Sine-Wave Speech. a Short Introduction by Manfred Bartmann

This material comes from <www.manfred-bartmann.de>. It forms part of Manfred Bartmann's CD Frisia Orientalis II: Making Music of Speech © 2017 Manfred Bartmann. The information, text, photo, graphic, audio and/or video material or other materials shall not be published, broadcast, rewritten for broadcast or publication or redistributed directly or indirectly in any medium in whole or in part without express written permission. Neither these materials nor any portion thereof may be stored or used on a computer except for personal use. In case of doubt, please contact <[email protected]>. MB. Sine-wave Synthesis, or Sine-wave Speech. A Short Introduction by Manfred Bartmann On the CD, three tracks make use of sine-wave syntheses: No. 3 April '84 - fieldworking in East Frisia, No. 4 An East Frisian farm-hand song (Deenstenleed) revisited, and No. 5 Rökeldoab Dada, a grooving Low German mouth music. For further information on these tracks please refer to the corresponding booklet entries. Please also refer to the sound files embedded in this document. Their playback requires an applicable PDF-viewer. © Adobe Reader XI will do. The pure-tone whistles within these tracks may remind one of warbling sounds for which R2-D2, an astromech droid popularised by the Star Wars movies, has become famous. ... please note that we did not hire R2-D2 as a studio musician ! R2-D2's iconic sounds were created by sound designer Ben Burtt, and I always had thought that he had used a software developed by Philip Rubin way back then for the purpose of what was to be called sine-wave synthesis (Rubin 1982). -

COMMITTEE TRUSTEES: Philip Rubin, Sandy Cloud

MINUTES SPECIAL MEETING OF THE BOT COMMITTEE FOR RESEARCH, ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND INNOVATION University of Connecticut Room 216, Hartford Campus Hartford Connecticut January 23, 2020 COMMITTEE TRUSTEES: Philip Rubin, Sandy Cloud (via telephone), Marilda Gandara (via telephone) ADDITIONAL TRUSTEES: Shari Cantor (via telephone), Tom Ritter, Dan Toscano (via telephone) COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Rich Vogel UNIVERSITY SENATE REP: Rajeev Bansal STAFF: Gail Garber, Radenka Maric, David Nobel, Rachel Rubin, John Volin, Dana Wine, Rita Zangari GUEST: David Steuber, CTNext, formerly of Senator Fonfara’s Office Committee Vice Chair Rubin convened the meeting of the Committee for Research, Entrepreneurship and Innovation at 10 a.m. on January 23, 2020. Vice Chair Rubin said the meeting’s purpose was to discuss the Technology Transfer Plan which required Board of Trustees approval by March 1. He confirmed that all had access to the plan which was forwarded in December and noted that the most recent version includes a draft budget. Committee Vice Chair Rubin asked Dr. Maric to begin her presentation. Dr. Maric noted that Vice Provost John Volin is responsible for the faculty hiring plan referenced in the tech transfer plan and described in PA 19-154; that Dr. Noble is responsible for the Werth Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship that supports student entrepreneurship; and that she is responsible for technology transfer and venture development Dr. Maric outlined requirements and foci of the plan along with committee comments received and how they were addressed in the plan. Dr. Maric noted that her office has already begun to act on the plan where no new resources are required. -

A Million to One: Changing the Odds

A Million to One: Changing the Odds Ubuntu Education Fund 2014 Annual Report BUILDing a sustainable Dear Friends, institution Invest in people and a centre that inspires Think, for a moment, about everything that it Impact the highest standard took for you to get to where you are today—all through the investments that your family, friends, and depth teachers made in you. The list seems endless Produce lasting THE Based in the when you really start to reflect on it. The hugs, change through community pep talks, and advice; the vaccines, Band-Aids, significant and UBUNTU Listen to the town- and doctor appointments; the pre-school classes, focused investment MODEL ships’ needs and SAT prep tutors, and university seminars. It’s overwhelming to try to remember utilize their resources just how many people supported you along the way, because none of us can say through strategic partnerships that we have achieved success entirely on our own. Cradle Now, consider a child orphaned by HIV, growing up in a home constructed to career with aluminum scrap metal; hunger, inadequate healthcare, and a grossly un- Create individualized pathways to equal education system overshadow so many of her dreams. The odds are meet each client’s household, health, stacked against her, a million to one. Wouldn’t it logically take the same invest- and educational needs ments for this vulnerable child to move from point A to point B? Wouldn’t it probably take more? At Ubuntu, we believe that not only does breaking the poverty trap for one child take a million interventions but also that our cradle to career approach is the only way to achieve sustainable development. -

LONG-TERM MEMBERS 25+ Years of Membership

LONG-TERM MEMBERS 25+ Years of Membership Stuart A. Aaronson, MD Stephen P. Ackland, MBBS Carol Aghajanian, MD Steven A. Akman, MD Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai University of Newcastle Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Roper St. Francis Healthcare United States Australia United States United States Active Member Active Member Active Member Active Member 38 Years of Membership 33 Years of Membership 27 Years of Membership 35 Years of Membership Cory Abate-Shen, PhD Edward M. Acton, PhD Irina U. Agoulnik, PhD Emmanuel T. Akporiaye, PhD Columbia University Irving Medical United States Florida International University Verana Therapeutics Center Emeritus Member United States United States United States 42 Years of Membership Active Member Emeritus Member Active Member 25 Years of Membership 31 Years of Membership 26 Years of Membership David J. Adams, PhD Duke University Medical Center Imran Ahmad, PhD Ala-Eddin Al Moustafa, PhD James L. Abbruzzese, MD United States Northwestern Medicine McGill University Duke University Emeritus Member United States Canada United States 32 Years of Membership Active Member Active Member Active Member 25 Years of Membership 26 Years of Membership 32 Years of Membership Gregory P. Adams, PhD Elucida Oncology Nihal Ahmad, PhD Abdul Al Saadi, PhD Ehtesham A. Abdi, MBBS United States Univ. of Wisconsin Madison Sch. of Med. William Beaumont Hospital The Tweed Hospital Active Member & Public Health United States Australia 29 Years of Membership United States Emeritus Member Emeritus Member Active Member 52 Years of Membership 33 Years of Membership Lucile L. Adams-Campbell, PhD 25 Years of Membership Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Suresh K.