The Conductor Model of Online Speech Modulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of a Text to Speech System for Devanagari Konkani

DEVELOPMENT OF A TEXT TO SPEECH SYSTEM FOR DEVANAGARI KONKANI A Thesis submitted to Goa University for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science and Technology By Nilesh B. Fal Dessai GOA UNIVERSITY Taleigao Plateau May 2017 Development of a Text to Speech System for Devanagari Konkani A Thesis submitted to Goa University for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science and Technology By Nilesh B. Fal Dessai GOA UNIVERSITY Taleigao Plateau May 2017 Statement As required under the ordinance OB-9.9 of Goa University, I, Nilesh B. Fal Dessai, state that the present Thesis entitled, ‘Development of a Text to Speech System for Devanagari Konkani’ is my original contribution carried out under the supervision of Dr. Jyoti D. Pawar, Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science and Technology, Goa University and the same has not been submitted on any previous occasion. To the best of my knowledge, the present study is the first comprehensive work of its kind in the area mentioned. The literature related to the problem investigated has been cited. Due acknowledgments have been made whenever facilities and suggestions have been availed of. (Nilesh B. Fal Dessai) i Certificate This is to certify that the thesis entitled ‘Development of a Text to Speech System for Devanagari Konkani’, submitted by Nilesh B. Fal Dessai, for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science and Technology is based on his original studies carried out under my supervision. The thesis or any part thereof has not been previously submitted for any other degree or diploma in any University or Institute. -

The Routledge Handbook of Embodied Cognition

THE ROUTLEDGE HANDBOOK OF EMBODIED COGNITION Embodied cognition is one of the foremost areas of study and research in philosophy of mind, philosophy of psychology and cognitive science. The Routledge Handbook of Embodied Cognition is an outstanding guide and reference source to the key philosophers, topics and debates in this exciting subject and essential reading for any student and scholar of philosophy of mind and cognitive science. Comprising over thirty chapters by a team of international contributors, the Handbook is divided into six parts: Historical underpinnings Perspectives on embodied cognition Applied embodied cognition: perception, language, and reasoning Applied embodied cognition: social and moral cognition and emotion Applied embodied cognition: memory, attention, and group cognition Meta-topics. The early chapters of the Handbook cover empirical and philosophical foundations of embodied cognition, focusing on Gibsonian and phenomenological approaches. Subsequent chapters cover additional, important themes common to work in embodied cognition, including embedded, extended and enactive cognition as well as chapters on embodied cognition and empirical research in perception, language, reasoning, social and moral cognition, emotion, consciousness, memory, and learning and development. Lawrence Shapiro is a professor in the Department of Philosophy, University of Wisconsin – Madison, USA. He has authored many articles spanning the range of philosophy of psychology. His most recent book, Embodied Cognition (Routledge, 2011), won the American Philosophical Association’s Joseph B. Gittler award in 2013. Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy are state-of-the-art surveys of emerging, newly refreshed, and important fields in philosophy, providing accessible yet thorough assessments of key problems, themes, thinkers, and recent developments in research. -

COMMITTEE TRUSTEES: Philip Rubin, Mark Boxer, Sandy Cloud

DRAFT MINUTES SPECIAL TELEPHONE MEETING OF THE COMMITTEE FOR RESEARCH, ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND INNOVATION University of Connecticut Board of Trustees February 15, 2021 COMMITTEE TRUSTEES: Philip Rubin, Mark Boxer, Sandy Cloud, Marilda Gandara ADDITIONAL TRUSTEES: Chairman Toscano COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Rich Vogel, Tim Shannon UNIVERSITY SENATE REP: Jeannette Pritchard STAFF: Joanna Desjardin, President Katsouleas, Radenka Maric, David Nobel, Rachel Rubin, Dan Schwartz, Jeffrey Shoulson, Dan Weiner Committee Vice Chair Rubin convened the meeting at 10:01 a.m. by telephone. No public comment was volunteered on any of the agenda items. On a motion by Trustee Cloud, seconded by Mr. Vogel, the minutes from the November 16, 2020, Special Meeting of the REI Committee were approved. Vice Chair Rubin informed the committee that University Senate Representative Dr. Rajeev Bansal has retired and welcomed Dr. Jeanette Pritchard as the University Senate Representative on the committee. Vice Chair Rubin gave opening remarks and presented the publication, UConn in the Media. If anyone wants a copy they can contact Vice Chair Rubin or Joanna Desjardin. Congratulated Dr. David Noble for a featured article in UConn Today on entrepreneurship. Congratulated Dr. Radenka Maric for becoming a member of AAAS and her publication, Atomistic Insights into the Hydrogen Oxidation Reaction of Palladium-Ceria Bifunctional Catalysts for Anion-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells, which is about her important work she and her colleagues continue to do on fuel cells. Would like to hear more about this at a future meeting. Welcomed Dr. Daniel Weiner, Vice President for Global Affairs, to the meeting. Vice Chair Rubin introduced Dr. Radenka Maric, Vice President for Research, Innovation & Entrepreneurship. -

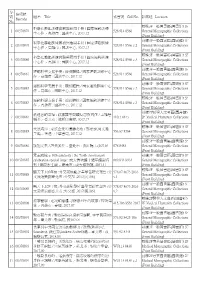

序號no. 條碼號barcode 題名title 索書號call No. 館藏地location 1

序 條碼號 號 題名 Title 索書號 Call No. 館藏地 Location Barcode No. 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 科學化體能訓練實務與應用手冊 / 國家運動訓練 1 00370878 528.914 8566 General Monographic Collections 中心作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 科學化體能訓練實務與應用手冊 / 國家運動訓練 2 00370879 528.914 8566 c.2 General Monographic Collections 中心作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 科學化體能訓練實務與應用手冊 / 國家運動訓練 3 00370880 528.914 8566 c.3 General Monographic Collections 中心作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 運動科學支援手冊 : 競技體操 / 國家運動訓練中心 4 00370881 528.914 8566 General Monographic Collections 作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 運動科學支援手冊 : 競技體操 / 國家運動訓練中心 5 00370882 528.914 8566 c.2 General Monographic Collections 作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 運動科學支援手冊 : 競技體操 / 國家運動訓練中心 6 00370883 528.914 8566 c.3 General Monographic Collections 作 .- 高雄市 : 國訓中心, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟2F醫學人文專區(圖書館) 被遺忘的幸福 : 敘事醫學閱讀反思與寫作 / 王雅慧 7 00370884 410.3 8443 2F Medical Humanity Collections 編著 .- 臺北市 : 城邦印書館, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 大浪淘沙 : 家族企業的優勝劣敗 / 鄭宏泰,周文港 8 00370885 553.67 8764 General Monographic Collections 主編 .- 香港 : 中華書局, 2017.12 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 9 00370886 旅加文集 / 許業武作 .- 臺北市 : 黃紅梅, 民107.04 078 8483 General Monographic Collections (Front Building) 眾志成城 = 10th solidarity : the Tenth Anniversary 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F 10 00370887 celebration special issue : 成大博物館十週年館慶特 069.833 8933 General Monographic Collections 刊 / 陳政宏主編 .- 臺南市 : 成大博物館, 2017.11 (Front Building) 前棟3F一般圖書區(圖書館) 3F -

Universidade Do Algarve

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sapientia UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE Quebra de barreiras de comunica»c~aopara portadores de paralisia cerebral. Paulo Alexandre Lucas Afonso Condado Doutoramento em Engenharia Electr¶onicae Computa»c~ao Ci^enciasde Computa»c~ao 2009 UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE Quebra de barreiras de comunica»c~aopara portadores de paralisia cerebral. Paulo Alexandre Lucas Afonso Condado Tese orientada por Professor Fernando Miguel Pais da Gra»caLobo Doutoramento em Engenharia Electr¶onicae Computa»c~ao Ci^enciasde Computa»c~ao 2009 Resumo Nos ¶ultimosanos, o estudo das tecnologias de acessibilidade tem adquirido relev^anciana ¶areade interfaces pessoa-m¶aquina. O desenvolvimento de dis- positivos, m¶etodos, e aplica»c~oesespeci¯camente desenhadas para superar as limita»c~oesdos utilizadores facilita a interac»c~aodestes com o mundo exterior. A import^anciado estudo nesta ¶area¶eenorme, visto facilitar a interac»c~ao dos portadores de de¯ci^enciascom os meios tecnol¶ogicosque, por sua vez, possibilitam-lhes uma melhor comunica»c~aoe interac»c~aocom os outros, con- tribuindo signi¯cativamente para a sua integra»c~aona sociedade. Esta disserta»c~aoapresenta um sistema inovador, conhecido por Easy- Voice, que integra diversas tecnologias para permitir que uma pessoa com de¯ci^enciasna fala possa efectuar chamadas telef¶onicasusando uma voz sintetizada. Subjacente a este sistema, desenhado com o objectivo de dis- ponibilizar um interface acess¶³vel at¶epara utilizadores que possuam graves problemas de coordena»c~aomotora, est¶ao conceito que ¶eposs¶³vel combinar tecnologias j¶aexistentes para criar mecanismos que facilitem a comunica»c~ao dos portadores de de¯ci^enciasa longas dist^ancias,nomeadamente as tecno- logias de s¶³ntese de voz, voz sobre IP (VoIP) e m¶etodos de interac»c~aopara portadores de limita»c~oesmotoras. -

TADA (Task Dynamics Application) Manual

TADA (TAsk Dynamics Application) manual Copyright Haskins Laboratories, Inc., 2001-2006 300 George Street, New Haven, CT 06514, USA written by Hosung Nam ([email protected]), Louis Goldstein ([email protected]) Developers: Catherine Browman, Louis Goldstein, Hosung Nam, Philip Rubin, Michael Proctor, Elliot Saltzman (alphabetical order) Description The core of TADA is a new MATLAB implementation of the Task Dynamic model of inter-articulator coordination in speech (Saltzman & Munhall, 1989). This functional coordination is accomplished with reference to speech Tasks, which are defined in the model as constriction Gestures accomplished by the various vocal tract constricting devices. Constriction formation is modeled using task-level point-attractor dynamical systems that guide the dynamical behavior of individual articulators and their coupling. This implementation includes not only the inter-articulator coordination model, but also • a planning model for inter-gestural timing, based on coupled oscillators (Nam et al, in prog) • a model (GEST) that generates the gestural coupling structure (graph) for an arbitrary English utterance from text input (either orthographic or an ARPABET transcription). Functionality TADA implements three models that are connected to one another as illustrated by the boxes in Figure 1. 1. Syllable structure-based gesture coupling model Takes as input a text string and generates an intergestural coupling graph, that specifies the gestures composing the utterance (represented in terms of tract variable dynamical parameters and articulator weights) and the coupling relations among the gestures’ timing oscillators. 2. Coupled oscillator model of inter-gestural coordination Takes as input a coupling graph, and generates a gestural score, that specifies activation intervals in time for each gesture. -

Radical Embodied Cognitive Science Anthony Chemero

Radical Embodied Cognitive Science Anthony Chemero Radical Embodied Cognitive Science Radical Embodied Cognitive Science Anthony Chemero A Bradford Book The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England ( 2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any elec- tronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email [email protected] or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Stone Serif and Stone Sans on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong, and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chemero, Anthony, 1969–. Radical embodied cognitive science / Anthony Chemero. p. cm.—(A Bradford Book) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-01322-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Perception—Research. 2. Cognitive science. I. Title. BF311.B514 2009 153—dc22 2009001697 10987654321 For the crowd at Sweet William’s Pub Contents Preface: In Praise of Dr. Fodor ix Acknowledgments xiii I Stage Setting 1 1 Hegel, Behe, Chomsky, Fodor 3 2 Embodied Cognition and Radical Embodied Cognition 17 II Representation and Dynamics 45 3 Theories of Representation 47 4 The Dynamical Stance 67 5 Guides to Discovery 85 III Ecological Psychology 103 6 Information and Direct Perception 105 7 Affordances, etc. 135 IV Philosophical Consequences 163 8 Neurophilosophy Meets Radical Embodied Cognitive Science 165 9 The Metaphysics of Radical Embodiment 183 10 Coda 207 Notes 209 References 221 Index 245 Preface: In Praise of Dr. -

Voice Synthesizer Application Android

Voice synthesizer application android Continue The Download Now link sends you to the Windows Store, where you can continue the download process. You need to have an active Microsoft account to download the app. This download may not be available in some countries. Results 1 - 10 of 603 Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next See also: Speech Synthesis Receming Device is an artificial production of human speech. The computer system used for this purpose is called a speech computer or speech synthesizer, and can be implemented in software or hardware. The text-to-speech system (TTS) converts the usual text of language into speech; other systems display symbolic linguistic representations, such as phonetic transcriptions in speech. Synthesized speech can be created by concatenating fragments of recorded speech that are stored in the database. Systems vary in size of stored speech blocks; The system that stores phones or diphones provides the greatest range of outputs, but may not have clarity. For specific domain use, storing whole words or suggestions allows for high-quality output. In addition, the synthesizer may include a vocal tract model and other characteristics of the human voice to create a fully synthetic voice output. The quality of the speech synthesizer is judged by its similarity to the human voice and its ability to be understood clearly. The clear text to speech program allows people with visual impairments or reading disabilities to listen to written words on their home computer. Many computer operating systems have included speech synthesizers since the early 1990s. A review of the typical TTS Automatic Announcement System synthetic voice announces the arriving train to Sweden. -

Book XIV Art and Psychology

8 88 88 88ycology 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XIV - Art and Psychology Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Visual perception ........................................... 1 1.1.1 Visual system ......................................... 1 1.1.2 Study ............................................. 1 1.1.3 The cognitive and computational approaches ......................... 3 1.1.4 Transduction ......................................... 4 1.1.5 Opponent process ....................................... 4 1.1.6 Artificial visual perception .................................. 4 1.1.7 See also ............................................ 4 1.1.8 Further reading ........................................ 4 1.1.9 References .......................................... 4 1.1.10 External links ......................................... 5 1.2 Depth perception ........................................... 6 1.2.1 Monocular cues ........................................ 6 1.2.2 Binocular cues ........................................ 7 1.2.3 Theories of evolution ..................................... 8 1.2.4 In art ............................................. 8 1.2.5 Disorders affecting depth perception ............................. 9 1.2.6 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.7 References .......................................... 9 1.2.8 Bibliography ......................................... 10 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 10 2 Day 2 11 2.1 Human eye ............................................. -

Carol A. Fowler's Perspective on Language by Eye

Ecological Psychology ISSN: 1040-7413 (Print) 1532-6969 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/heco20 Carol A. Fowler's Perspective on Language by Eye Donald Shankweiler To cite this article: Donald Shankweiler (2016) Carol A. Fowler's Perspective on Language by Eye, Ecological Psychology, 28:3, 130-137, DOI: 10.1080/10407413.2016.1195182 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10407413.2016.1195182 Published online: 02 Aug 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 133 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=heco20 ECOLOGICAL PSYCHOLOGY 2016, VOL. 28, NO. 3, 130–137 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10407413.2016.1195182 Carol A. Fowler’s Perspective on Language by Eye 1931 Donald Shankweilera,b aDepartment of Psychology, University of Connecticut; bHaskins Laboratories ABSTRACT This article considers highlights of Carol Fowler’s development as a scientist against the background of major developments in the fields of ecological psychology, speech research, and the psychology of language. Beginning from her graduate student years, the focus is on those aspects of Fowler’s research that pertain most directly to the relations between speech and reading. Graduate studies in the psychology of perception and language Carol Fowler, who as an undergraduate had begun the study of psychology and language at Brown University, moved to the University of Connecticut for graduate work arriving in 1971. She says she chose the University of Connecticut because while at Brown, at the suggestion of oneofherprofessors,shehadreadandadmiredanarticle,“Perception of the Speech Code” (A.M.Libermanetal.,1967), by University of Connecticut Professor Alvin M. -

Anthony Chemero

III Ecological Psychology The rules that govern behavior are not like laws enforced by an authority or decisions made by a commander: behavior is regular without being regulated. The question is how this can be. —James J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (1979) 6 Information and Direct Perception The purpose of this chapter and the next is to describe Gibsonian ecologi- cal psychology and to show that it can serve as an appropriate theoretical backdrop for radical embodied cognitive science. It hardly makes sense to do so other than in the context of the theoretical work of Michael Turvey, Robert Shaw, and William Mace. Since the 1970s, Turvey, Shaw, and Mace have worked on the formulation of a philosophically sound and empiri- cally tractable version of James Gibson’s ecological psychology. It is surely no exaggeration to say that without their theoretical work ecological psy- chology would have died on the vine because of high-profile attacks from establishment cognitive scientists (e.g., Fodor and Pylyshyn 1981). But thanks to Turvey, Shaw, and Mace’s work as theorists and, perhaps more important, as teachers, ecological psychology is currently flourishing. A generation of students, having been trained by Turvey, Shaw, and Mace at Trinity College and/or the University of Connecticut, are now distin- guished experimental psychologists who train their own students in Turvey-Shaw-Mace ecological psychology. Despite the undeniable and last- ing importance of Turvey, Shaw, and Mace’s theoretical contributions for psychology and the other cognitive sciences, their work has not received much attention from philosophers. -

Language and Social Behavior

Language and Social Behavior Robert M. Krauss and Chi-Yue Chiu Columbia University and The University of Hong-Kong Acknowledgments: We have benefitted from discussions with Kay Deaux, Susan Fussell, Julian Hochberg, Ying-yi Hong, and Lois Putnam. Yihsiu Chen, E. Tory Higgins, Robert Remez, Gün Semin, and the Handbook's editors read and commented on an earlier version of this chapter. The advice, comments and suggestions we have received are gratefully acknowledged, but the authors retain responsibility for such errors, misapprehensions and misinterpretations as remain. We also acknowledge support during the period this chapter was written from National Science Foundation grant SBR-93-10586, and from the University Research Council of the University of Hong Kong (Grant #HKU 162/95H). Note: This is a pre-editing copy of a chapter that appears in In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske & G. Lindsey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (4h ed.), Vol. 2. (pp. 41-88). Boston: McGraw-Hill. Language and Social Behavior Language and Social Behavior Language pervades social life. It is the principal vehicle for the transmission of cultural knowledge, and the primary means by which we gain access to the contents of others' minds. Language is implicated in most of the phenomena that lie at the core of social psychology: attitude change, social perception, personal identity, social interaction, intergroup bias and stereotyping, attribution, and so on. Moreover, for social psychologists, language typically is the medium by which subjects' responses are elicited, and in which they respond: in social psychological research, more often than not, language plays a role in both stimulus and response.