American Journal of Numismatics 23

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

Abd-Hadad, Priest-King, Abila, , , , Abydos, , Actium, Battle

INDEX Abd-Hadad, priest-king, Akkaron/Ekron, , Abila, , , , Akko, Ake, , , , Abydos, , see also Ptolemaic-Ake Actium, battle, , Alexander III the Great, Macedonian Adaios, ruler of Kypsela, king, –, , , Adakhalamani, Nubian king, and Syria, –, –, , , , Adulis, , –, Aegean Sea, , , , , , –, and Egypt, , , –, , –, – empire of, , , , , , –, legacy of, – –, –, , , death, burial, – Aemilius Paullus, L., cult of, , , Aeropos, Ptolemaic commander, Alexander IV, , , Alexander I Balas, Seleukid king, Afrin, river, , , –, – Agathokleia, mistress of Ptolemy IV, and eastern policy, , and Demetrios II, Agathokles of Syracuse, , –, and Seventh Syrian War, –, , , Agathokles, son of Lysimachos, – death, , , , Alexander II Zabeinas, , , Agathokles, adviser of Ptolemy IV, –, , , –, Alexander Iannai, Judaean king, Aigai, Macedon, , – Ainos, Thrace, , , , Alexander, son of Krateros, , Aitolian League, Aitolians, , , Alexander, satrap of Persis, , , –, , , – Alexandria-by-Egypt, , , , , , , , , , , , , Aitos, son of Apollonios, , , –, , , Akhaian League, , , , , , , –, , , , , , , , , , , , , , Akhaios, son of Seleukos I, , , –, –, , – , , , , , , –, , , , Akhaios, son of Andromachos, , and Sixth Syrian War, –, adviser of Antiochos III, , – Alexandreia Troas, , conquers Asia Minor, – Alexandros, son of Andromachos, king, –, , , –, , , –, , , Alketas, , , Amanus, mountains, , –, index Amathos, Cyprus, and battle of Andros, , , Amathos, transjordan, , Amestris, wife of Lysimachos, , death, Ammonias, Egypt, -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Bibliographic Information Permanent URL Copyright Information

Apian, Petrus, Cosmographia, 1550 Bibliographic information Author: Apian, Petrus Title: Cosmographia Year: 1550 City: Antwerpiae Publisher: Bontius Number of Pages: [2], 65, [1] Bl. : Ill. Permanent URL Document ID: MPIWG:WBGMR64C Permanent URL: http://echo.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/MPIWG:WBGMR64C Copyright information Copyright: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (unless stated otherwise) License: CC-BY-SA (unless stated otherwise) Table of contents 1. Page: 0 2. COSMOG RAPHIA PETRI APIANI, PER GEMMAM FRISIVM apud Louanienſes Medicum & Mathematicum inſ iam demum ab omnibus vindicata mendis nullis quoq; locis aucta. Additis eiuſde menti libellis ipſius Gemmæ Fr Page: 3 3. Contenta in hoc libro. Page: 4 4. PETRI APIANI Page: 4 5. GEMMÆ FRISII Page: 4 6. DIDACI PYRRHI LVSI-TANI CARMEN. Page: 4 7. DISTICHON. Page: 4 8. R. D. ET ILLVST. PRINCIPI, D. Matthæo, M. Diuina Sacroſanctæ Rho. Ec-cleſiæ Tit.S. Angeli Preſ. Card. Archiepiſco po Saltzburgeñ, Ap. Sed. Legato. &c. Petrus Apianus (dictus Benewitz) ex Leyſnick Mathematicæ diſciplinæ clientu-lus, Salutem perpetuam ac ſui ipſius commenda tionem. Page: 5 9. Prima pars huius libri de Coſmographiæ & Geographiœ principijs. QVID SIT COSMOGRAPHIA, Et quo differat à Geographia & Chorographia. CAPVT PRIMVM. Page: 7 10. GEOGR APHIA QVID. Page: 8 11. CHOROGRAPHIA QVID. Page: 9 12. DE MOTV SPHÆRARVM, Cœlorumq́ue diuiſione. CAP. II. Page: 10 13. DE CIRCVLIS SPHÆRÆ. CAP. III. Page: 11 14. QVID SPHÆRA. Page: 12 15. ¶ Quid axis Sphæræ. Page: 12 16. Deſex circulis ſphæræ MAIORIBVS. Page: 12 17. ¶ De quatuor Circulis minoribus. Page: 13 18. ¶ Sequitur materialis figura Circulorum Sphæræ. Page: 13 19. ¶ Diuiſionis præmiſſæ formula in plano extenſa. -

Prof. Dr. Orhan AYDIN Rektör DAĞITIM Üniversitemiz Uygulamalı

T.C. TARSUS ÜNİVERSİTESİ REKTÖRLÜĞÜ Genel Sekreterlik Sayı : E-66676008-051.01-84 02.03.2021 Konu : Kongre Duyurusu DAĞITIM Üniversitemiz Uygulamalı Bilimler Fakültesi ev sahipliğinde, Mersin Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi, Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi, Osmaniye Korkut Ata Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi ve Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi işbirliği ile ortaklaşa düzenlenen 08-09 Ekim 2021 tarihleri arasında çevrimiçi olarak gerçekleştirilecek olan “ Uluslararası Dijital İşletme, Yönetim ve İktisat Kongresi (International Digital Business, Management And Economics Congress)’ne ilişkin afiş görseli ekte gönderilmekte olup kongre hakkındaki detaylı bilgilere icdbme2021.tarsus.edu.tr adresinden ulaşılabilecektir. Söz konusu kongrenin kurumunuz ilgili birimlerine ve akademik personeline duyurulması hususunda ; Bilgilerinizi ve gereğini arz ederim. Prof. Dr. Orhan AYDIN Rektör Ek : Afiş (2 Sayfa) Dağıtım : Abdullah Gül Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Acıbadem Mehmet Ali Aydınlar Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Adana Alparslan Türkeş Bilim ve Teknoloji Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Adıyaman Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Akdeniz Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Aksaray Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Alanya Hamdullah Emin Paşa Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Amasya Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Anadolu Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Anka Teknoloji Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Ankara -

Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics Title The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xh6g8nn Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics, 2(1) ISSN 2373-7115 Author Gavryushkina, Marina Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gavryushkina 1 The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013 Abstract: Hellenistic coinage is a popular topic in art historical research as it is an invaluable resource of information about the political relationship between Greek rulers and their subjects. However, most scholars have focused on the wealthier and more famous dynasties of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Thus, there have been considerably fewer studies done on the artistic styles of the coins of the smaller outlying Hellenistic kingdoms. This paper analyzes the numismatic portraiture of the kings of Pontus, a peripheral kingdom located in northern Anatolia along the shores of the Black Sea. In order to evaluate the degree of similarity or difference in the Pontic kings’ modes of representation in relation to the traditional royal Hellenistic style, their coinage is compared to the numismatic depictions of Alexander the Great of Macedon. A careful art historical analysis reveals that Pontic portrait styles correlate with the individual political motivations and historical circumstances of each king. Pontic rulers actively choose to diverge from or emulate the royal Hellenistic portrait style with the intention of either gaining support from their Anatolian and Persian subjects or being accepted as legitimate Greek sovereigns within the context of international politics. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Poetry South

Poetry South Issue 11 2019 Poetry South Editor Kendall Dunkelberg Contributing & Angela Ball, University of Southern Mississippi Advisory Editors Carolyn Elkins, Tar River Poetry Ted Haddin, University of Alabama at Birmingham John Zheng, Mississippi Valley State University Assistant Editors Diane Finlayson Elizabeth Hines Dani Putney Lauren Rhoades Tammie Rice Poetry South is a national journal of poetry published annually by Mississippi University for Women (formerly published by Yazoo River Press). The views expressed herein, except for editorials, are those of the writers, not the editors or Mississippi University for Women. Poetry South considers submissions year round. Submissions received after the deadline of July 15 will be considered for the following year. No previously published material will be accepted. Poetry South is not responsible for unsolicited submissions and their loss. Submissions are accepted through Submittable: https://poetrysouth.submittable.com/ Subscription rates are $10 for one year, $18 for two years; the foreign rate is $15 for one year, $30 for two years. All rights revert to the authors after publication. We request Poetry South be credited with initial publication. Queries or other correspondence may be emailed to: [email protected]. Queries and subscriptions sent by mail should be addressed to: Poetry South, MFA Creative Writing, 1100 College St., W-1634, Columbus MS 39701. ISSN 1947-4075 (Print) ISSN 2476-0749 (Online) Copyright © 2019 Mississippi University for Women Indexed by EBSCOHost/Literary -

1 Eastern Europe. Imitation of Philip II of Macedon 320-280 BC

1 Eastern Europe. Imitation of Philip II of Macedon 320-280 BC. Tetradrachm AR 23mm., 13,63g. Laureate head of Zeus right / ΦΙΛIΠ-OY, young jockey, holding palm branch and reins, riding horse to right, below horse, Λ over torch, below horse's foreleg dolphin swimming right. very fine Le Rider pl. 48, 1. SNG ANS 807. Starting price: 80 EUR 2 Eastern Europe. Imitation of Philip II of Macedon 300-200 BC. Tetradrachm AR 24mm., 14,24g. Laureate head of Zeus right / ΦIΛIΠΠ-OY, youth on horseback right, holding palm, thunderbolt and I below, ME monogram below raised foreleg. very fine Dembski 1015. Starting price: 150 EUR 3 Eastern Europe. Imitation of Philip II of Macedon 300-200 BC. Drachm AR 14mm., 2,79g. Laureate head of Zeus right / Horse advancing left, wheel with four spokes above. good very fine Lanz 458-9; OTA 188/2-3. Starting price: 75 EUR 4 Eastern Europe. Imitation of Philip II of Macedon 200-0 BC. Tetradrachm AR 24mm., 13,91g. Laureate head of Zeus to right / ΦΙΛΙΠ-ΠΟΥ, nude jockey on horse prancing to right, holding long palm branch in his right hand, below horse, Λ above torch, monogram below raised foreleg. very fine Cf. Lanz 355-6; OTA 10/2. Starting price: 150 EUR 5 Eastern Europe. Imitation of Philip II of Macedon 100 BC. Tetradrachm AR 22mm., 9,03g. Celticized head of Zeus, right / Horseman, riding left. very fine Dembski 1095; OTA 147. Starting price: 80 EUR 6 Campania. Neapolis 340-241 BC. Didrachm AR 17mm., 7,30g. Diademed head of nymph right, lyre behind / Man-headed bull walking right, above, Nike flying right, placing wreath on bull's head, ΙΣ/ NEOΠOΛITΩN in exergue. -

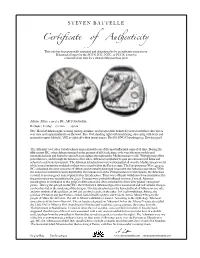

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

Stable Lead Isotope Studies of Black Sea Anatolian Ore Sources and Related Bronze Age and Phrygian Artefacts from Nearby Archaeological Sites

Archaeometry 43, 1 (2001) 77±115. Printed in Great Britain STABLE LEAD ISOTOPE STUDIES OF BLACK SEA ANATOLIAN ORE SOURCES AND RELATED BRONZE AGE AND PHRYGIAN ARTEFACTS FROM NEARBY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES. APPENDIX: NEW CENTRAL TAURUS ORE DATA E. V. SAYRE, E. C. JOEL, M. J. BLACKMAN, Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560, USA K. A. YENER Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, 1155 East 58th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA and H. OÈ ZBAL Faculty of Arts and Sciences, BogÆazicËi University, Istanbul, Turkey The accumulated published database of stable lead isotope analyses of ore and slag specimens taken from Anatolian mining sites that parallel the Black Sea coast has been augmented with 22 additional analyses of such specimens carried out at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Multivariate statistical analysis has been used to divide this composite database into ®ve separate ore source groups. Evidence that most of these ore sources were exploited for the production of metal artefacts during the Bronze Age and Phrygian Period has been obtained by statistically comparing to them the isotope ratios of 184 analysed artefacts from nine archaeological sites situated within a few hundred kilometres of these mining sites. Also, Appendix B contains 36 new isotope analyses of ore specimens from Central Taurus mining sites that are compatible with and augment the four Central Taurus Ore Source Groups de®ned in Yener et al. (1991). KEYWORDS: BLACK SEA, CENTRAL TAURUS, ANATOLIA, METAL, ORES, ARTEFACTS, BRONZE AGE, MULTIVARIATE, STATISTICS, PROBABILITIES INTRODUCTION This is the third in a series of papers in which we have endeavoured to evaluate the present state of the application of stable lead isotope analyses of specimens from metallic ore sources and of ancient artefacts from Near Eastern sites to the inference of the probable origins of such artefacts.