Orkney's Maritime Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scapa Flow Scale Site Environmental Description 2019

Scapa Flow Scale Test Site – Environmental Description January 2019 Uncontrolled when printed Document History Revision Date Description Originated Reviewed Approved by by by 0.1 June 2010 Initial client accepted Xodus LF JN version of document Aurora 0.2 April 2011 Inclusion of baseline wildlife DC JN JN monitoring data 01 Dec 2013 First registered version DC JN JN 02 Jan 2019 Update of references and TJ CL CL document information Disclaimer In no event will the European Marine Energy Centre Ltd or its employees or agents, be liable to you or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information in this report or for any consequential, special or similar damages, even if advised of the possibility of such damages. While we have made every attempt to ensure that the information contained in the report has been obtained from reliable sources, neither the authors nor the European Marine Energy Centre Ltd accept any responsibility for and exclude all liability for damages and loss in connection with the use of the information or expressions of opinion that are contained in this report, including but not limited to any errors, inaccuracies, omissions and misleading or defamatory statements, whether direct or indirect or consequential. Whilst we believe the contents to be true and accurate as at the date of writing, we can give no assurances or warranty regarding the accuracy, currency or applicability of any of the content in relation to specific situations or particular circumstances. Title: Scapa Flow Scale Test -

Results of the Seabird 2000 Census – Great Skua

July 2011 THE DATA AND MAPS PRESENTED IN THESE PAGES WAS INITIALLY PUBLISHED IN SEABIRD POPULATIONS OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND: RESULTS OF THE SEABIRD 2000 CENSUS (1998-2002). The full citation for the above publication is:- P. Ian Mitchell, Stephen F. Newton, Norman Ratcliffe and Timothy E. Dunn (Eds.). 2004. Seabird Populations of Britain and Ireland: results of the Seabird 2000 census (1998-2002). Published by T and A.D. Poyser, London. More information on the seabirds of Britain and Ireland can be accessed via http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-1530. To find out more about JNCC visit http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-1729. Table 1a Numbers of breeding Great Skuas (AOT) in Scotland and Ireland 1969–2002. Administrative area Operation Seafarer SCR Census Seabird 2000 Percentage Percentage or country (1969–70) (1985–88) (1998–2002) change since change since Seafarer SCR Shetland 2,968 5,447 6,846 131% 26% Orkney 88 2,0001 2,209 2410% 10% Western Isles– 19 113 345 1716% 205% Comhairle nan eilean Caithness 0 2 5 150% Sutherland 4 82 216 5300% 163% Ross & Cromarty 0 1 8 700% Lochaber 0 0 2 Argyll & Bute 0 0 3 Scotland Total 3,079 7,645 9,634 213% 26% Co. Mayo 0 0 1 Ireland Total 0 0 1 Britain and Ireland Total 3,079 7,645 9,635 213% 26% Note 1 Extrapolated from a count of 1,652 AOT in 1982 (Meek et al., 1985) using previous trend data (Furness, 1986) to estimate numbers in 1986 (see Lloyd et al., 1991). -

Cruising the ISLANDS of ORKNEY

Cruising THE ISLANDS OF ORKNEY his brief guide has been produced to help the cruising visitor create an enjoyable visit to TTour islands, it is by no means exhaustive and only mentions the main and generally obvious anchorages that can be found on charts. Some of the welcoming pubs, hotels and other attractions close to the harbour or mooring are suggested for your entertainment, however much more awaits to be explored afloat and many other delights can be discovered ashore. Each individual island that makes up the archipelago offers a different experience ashore and you should consult “Visit Orkney” and other local guides for information. Orkney waters, if treated with respect, should offer no worries for the experienced sailor and will present no greater problem than cruising elsewhere in the UK. Tides, although strong in some parts, are predictable and can be used to great advantage; passage making is a delight with the current in your favour but can present a challenge when against. The old cruising guides for Orkney waters preached doom for the seafarer who entered where “Dragons and Sea Serpents lie”. This hails from the days of little or no engine power aboard the average sailing vessel and the frequent lack of wind amongst tidal islands; admittedly a worrying combination when you’ve nothing but a scrap of canvas for power and a small anchor for brakes! Consult the charts, tidal guides and sailing directions and don’t be afraid to ask! You will find red “Visitor Mooring” buoys in various locations, these are removed annually over the winter and are well maintained and can cope with boats up to 20 tons (or more in settled weather). -

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

Download Property Schedule

FOR SALE The Knowe, Deerness , Orkney, KW17 2QH Offers Over £235,000 About The Sitting Room Property LOCATION The property is situated in the rural parish of Deerness, approximately 11 miles from Kirkwall, enjoying fine views towards Copinsay and over the surrounding countryside. ACCOMMODATION Accommodation comprises of vestibule, open plan sitting room / diner / kitchen, hallway, bathroom and 3 bedrooms. DESCRIPTION The Knowe is a well presented 3 bedroom detached single storey property with:- Kitchen Double glazed timber windows Oil fired central heating to radiators Solid fuel stove with stone surround & timber mantle to sitting room Bathroom – bath, shower cubicle, wash hand basin & W.C Kitchen – modern built in units with sink & drainer, Kensington gas cooker, Bosch washing machine & Siemens tumble dryer included in the sale Built in wardrobe to master bedroom Front and rear garden areas Detached garage with electric vehicle door Tarmac parking area Timber sheep shed Land extending to c.4 acres 2 hosted wind turbines on site providing free electricity This property would make an ideal family home and viewing is highly recommended to fully appreciate the property. Consideration may be given to selling the property without the sheep shed & land – further information available on request. www.dandhlaw.co.uk Internal Photographs Master Bedroom Bedroom 2 Kitchen Sitting Room / Diner Bathroom Bathroom www.dandhlaw.co.uk Ex ternal Photographs Front Garden Rear Garden Land Garage Sheep Shed View 8.4m x 4.5m 8.7m x 3.9m www.dandhlaw.co.uk Floor Plan www.dandhlaw.co.uk COUNCIL TAX The subjects are in Band D. The Council Tax Band may be re- assessed by the Orkney and Shetland Joint Board when the property is sold. -

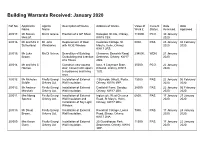

Building Warrants Received: January 2020

Building Warrants Received: January 2020 Ref No. Applicants Agents Description of Works. Address of Works. Value of Current Date Date Name. Name. Work £. Status. Received. Approved. 20/017. Mr Steven Ms Di Grieve. Erection of a GP Shed. Dalespot, St Ola, Orkney, 110000. PCO. 30 January Metcalf. KW15 1SX. 2020. 20/016. Mr and Mrs C Mr John Replacement of Door Cedarlea Cottage, St 5000. PAS. 28 January 04 February Sutherland. Winstanley. with MOE Window. Mary's, Holm, Orkney, 2020. 2020. KW17 2RS. 20/015. Mr Luke Ms Di Grieve. Demolition of Existing Glenavon, Denwick Road, 234000. WDN. 27 January Brown. Outbuilding and Erection Deerness, Orkney, KW17 2020. of a House. 2QQ. 20/014. Mr and Mrs C Construct new access Iona, 9 Claymore Brae, 35000. PCO. 22 January Harcus. stair, convert attic space Kirkwall, Orkney, KW15 2020. to bedrooms and living 1UQ. area. 20/013. Mr Nicholas Firefly Energi Installation of External 4 Burnside (West), Flotta, 13500. PAS. 22 January 06 February Biddle. Orkney Ltd. Wall Insulation. Orkney, KW16 3NP. 2020. 2020. 20/012. Mr Andrew Firefly Energi Installation of External Castlehill Farm, Sanday, 28000. PAS. 22 January 06 February Marshall. Orkney Ltd. Wall Insulation. Orkney, KW17 2BA. 2020. 2020. 20/011. Mrs Morag Firefly Energi Installation of External Ingleneuk, West Greaves 6800. PAS. 17 January 27 January Spence. Orkney Ltd. Wall Insulation and Road, St Mary's, Holm, 2020. 2020. Installation of Sky Light Orkney, KW17 2RU. Window. 20/010. Mr David Firefly Energi Installation of External Raviehall Cottage, Loons 7800. PAS. 17 January 24 January Brown. Orkney Ltd. -

The Kirk in the Garden of Evie

THE KIRK IN THE GARDEN OF EVIE A Thumbnail Sketch of the History of the Church in Evie Trevor G Hunt Minister of the linked Churches of Evie, Firth and Rendall, Orkney First Published by Evie Kirk Session Evie, Orkney. 1987 Republished 1996 ComPrint, Orkney 908056 Forward to the 1987 Publication This brief history was compiled for the centenary of the present Evie Church building and I am indebted to all who have helped me in this work. I am especially indebted to the Kirk’s present Session Clerk, William Wood of Aikerness, who furnished useful local information, searched through old Session Minutes, and compiled the list of ministers for Appendix 3. Alastair Marwick of Whitemire, Clerk to the Board, supplied a good deal of literature, obtained a copy of the Title Deeds, gained access to the “Kirk aboon the Hill”, and conducted a tour (even across fields in his car) to various sites. He also contributed valuable local information and I am grateful for all his support. Thanks are also due to Margaret Halcro of Lower Crowrar, Rendall, for information about her name sake, and to the Moars of Crook, Rendall, for other Halcro family details. And to Sheila Lyon (Hestwall, Sandwick), who contributed information about Margaret Halcro (of the seventeenth century!). TREVOR G HUNT Finstown Manse March 1987 Foreword to the 1996 Publication Nearly ten years on seemed a good time to make this history available again, and to use the advances in computer technology to improve its appearance and to make one or two minor corrections.. I was also anxious to include the text of the history as a page on the Evie, Firth and Rendall Churches’ Internet site for reference and, since revision was necessary to do this, it was an opportunity to republish in printed form. -

Records of Species and Subspecies Recorded in Scotland on up to 20 Occasions

Records of species and subspecies recorded in Scotland on up to 20 occasions In 1993 SOC Council delegated to The Scottish Birds Records Committee (SBRC) responsibility for maintaining the Scottish List (list of all species and subspecies of wild birds recorded in Scotland). In turn, SBRC appointed a subcommittee to carry out this function. Current members are Dave Clugston, Ron Forrester, Angus Hogg, Bob McGowan Chris McInerny and Roger Riddington. In 1996, Peter Gordon and David Clugston, on behalf of SBRC, produced a list of records of species recorded in Scotland on up to 5 occasions (Gordon & Clugston 1996). Subsequently, SBRC decided to expand this list to include all acceptable records of species recorded on up to 20 occasions, and to incorporate subspecies with a similar number of records (Andrews & Naylor 2002). The last occasion that a complete list of records appeared in print was in The Birds of Scotland, which included all records up until 2004 (Forrester et al. 2007). During the period from 2002 until 2013, amendments and updates to the list of records appeared regularly as part of SBRC’s Scottish List Subcommittee’s reports in Scottish Birds. Since 2014 these records have appear on the SOC’s website, a significant advantage being that the entire list of all records for such species can be viewed together (Forrester 2014). The Scottish List Subcommittee are now updating the list annually. The current update includes records from the British Birds Rarities Committee’s Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 2015 (Hudson 2016) and SBRC’s Report on rare birds in Scotland, 2015 (McGowan & McInerny 2017). -

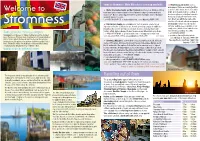

Stromness’ Main Attractions (See Map Overleaf): 14 New Library and Archive Offers A

© DiskArt™ 1988 © D iskArt™ 1988 ©DiskArt™1988 © Di skArt™ 1988 © D iskArt™ 1988 © DiskA rt 1989 © DiskArt™ 1988 Some of Stromness’ Main Attractions (see map overleaf): 14 New Library and Archive offers a © D iskArt ™ 1988 wide range of fiction and non-fiction titles Welcome to English 15 Visitor Information Centre and Bus Terminal information on all things Orkney as well as audio books, music CDs and a from travel and accommodation to sites of interest, nature & environment and bright, well stocked children’s section. It much more. Busses arrive/depart from here and the NorthLink ferry to Mainland also has a reference collection, housed in Scotland departs here also. the George Mackay Brown Room. In the t: +44(0)1856 850716 w: visitscotland.com open: May-Aug 0900-1700 main library you will find an up-to-date selection of local and national newspapers and magazines which you can enjoy in Stromness 12 The Pier Arts Centre was established in 1979 to provide a home for an important collection of British fine art. As well as hosting a range of exhibitions our foyer seating area, or upstairs on our throughout the year the permanent collection includes works by major 20th comfy sofas, which offer a fantastic view Century artists Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Alfred Wallis and others. over Stromness harbour. Free WiFi. Town guide for cruise passengers t: +44(0)1856 850209 w: pierartscentre.com e: [email protected] t: +44(0)1856 850907 Stromness lies in the west of Orkney, huddled around the sheltered open: Tues-Sat 1030-1700 & Jul-Aug Mondays 1030-1700 free entry e: [email protected] bay of Hamnavoe. -

History of Medicine

HISTORY OF MEDICINE The air-ambulance: Orkney's experience R. A. COLLACOTT, MA, DM, PH.D, MRCGP RCGP History of General Practice Research Fellow; formerly General Practitioner, Isle of Westray, Orkney Islands SUMMARY. The paramount problem for the de- isolated medical service. Patients could be transferred livery of the medical services in the Orkneys has between islands and from the islands to mainland been that of effective transport. The develop- Scotland. It became easier for general practitioners to ment of an efficient air-ambulance service has obtain the assistance of colleagues in other islands, had a major impact on medical care. The service which led to more effective specialist services in the started in 1934, but was abolished at the outset of main island townships of Kirkwall in the Orkney Isles, the Second World War and did not recommence Stornoway in the Hebrides and Lerwick in the Shetland until 1967. This paper examines the evolution of Isles. The air-ambulance made attending regional cen- the air-ambulance service in the Orkney Islands, tres such as Aberdeen easier and more comfortable for and describes alternative proposals for the use of patients than the conventional, slower journey by boat: aircraft in this region. for example, the St Ola steamer took four to five hours to sail between Kirkwall and Wick via Thurso whereas the plane took only 35 minutes; furthermore, patients Introduction often became more ill as a result of the sea journey alone, the Pentland Firth being notorious for its stormy UNLIKE the other groups of Scottish islands, the I Orkney archipelago a of seas. -

2018 50Th Anniversary Issue

Orkney Heritage Society 1968-2018 50th Anniversary Issue Objectives of the Orkney Heritage Society The aims of the Society are to promote and encourage the following objectives by charitable means: 1. To stimulate public interest in, and care for the beauty, history and character of Orkney. 2. To encourage the preservation, development and improvement of features of general public amenity or historical interest. 3. To encourage high standards of architecture and town planning in Orkney. 4. To pursue these ends by means of meetings, exhibitions, lectures, conferences, publicity and promotion of schemes of a charitable nature. New members are always welcome To learn more about the society and its ongoing work, check out the regularly updated website at www.orkneycommunities.co.uk/ohs or contact us at Orkney Heritage Society PO Box No. 6220 Kirkwall Orkney KW15 9AD Front Cover: Robert Garden and his wife, Margaret Jolly, along with one of their daughters standing next to the newly re-built Groatie Hoose. It got its name from the many shells, including ‘groatie buckies’, decorating the tower. Note the weather vane showing some of Garden’s floating shops. Photo gifted by Mrs Catherine Dinnie, granddaughter of Robert Garden. 1 Orkney Heritage Society Committee 2018 President: Sandy Firth, Edan, Berstane Road, Kirkwall, KW15 1NA [email protected] Vice President: Sheena Wenham, Withacot, Holm [email protected] Chairman: Spencer Rosie, 7 Park Loan, Kirkwall, KW15 1PU [email protected] Vice Chairman: David Murdoch, 13 -

British Rainfall, 1890

BRITISH RAINFALL, 1890. LONDON : G. .SHIELD, PHINTIill, SLOANE SQUARE, CHIiLSEA, 1891. DEPfH OF RAIN, JULY \r? 1890. SCALE 0 b 10 Miles 0 5 10 15 20 Kilom RAINFALL 2. in. and above O M l> n BRITISH RAINFALL,A 4890.., ON THE DISTRIBUTION OF RAIN OVER THE BRITISH ISLES, DURING THE YEAR 1890, AS OBSERVED AT NEARLY 3000 STATIONS IN GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND, WITH ARTICLES UPON VARIOUS BRANCHES OF RAINFALL WORK. COMPILED BY G. J. SYMONS, F.E.S., CHEVALIER DE LA LEGION D'HONNEUR, Secretary Royal Meteorological Society; Membredu Gonseil Societe Meteor ologique de France; Member Scottish Meteorological Society; Korrespondirendes Mitgleid Dtutsche Meteorologische Qesellschaft ; Registrar of Sanitary Institute ; Fellow Royal Colonial Institute ; Membre correspondant etranger Soc. Royale de Publique de Belgique, $c. fyc. cj'c.. AND H. SOWERBY WALLIS, F.R.MetSoc. LONDON: EDWARD STANFORD, COCKSPUR STREET, S.W. 1891. CONTENTS. PAGE PREFACE ... ... ... .. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. ... ... 7 REPORT—GENERAL OFFICE WORK—ENQUIRY AFTER OTHER OBSERVERS— OLD OBSERVATION Boons—RAINFALL RULES—SELF-RECORDING GAUGES—DAYS WITH RATN—FINANCE ... ... ... ... ... .. ... 8 ON THE AMOUNT OF EVAPORATION .. ... ... .. ... ... ... ... 17 THE CAMDEN SQUARE EVAPORATION EXPERIMENTS ... ... ... ... ... 30 ON THE FLUCTUATION IN THE AMOUNT OF RAINFALL ... ... ... ... ... 32 ROTHERHAM EXPERIMENTAL GAUGES .. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 3~> RAINFALL AT THE ROYAL OBSERVATORY, GREENWICH ... .. ... ... 37 THE STAFF OF OBSERVERS ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 38 OBITUARY ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 54 RAINFALL AND METEOROLOGY OF 1890. ON THE METEOROLOGY OF 1890, WITH NOTES ON SOME OF THE PRINCIPAL PHENOMENA ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. ... [ 3 ] OBSERVERS' NOTES ox THE MONTHS OF 1890 ... ... ... .., ... ... [ 35] OBSERVERS' NOTES ON THE YEAR 1890 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... [ 70] HEAVY RAIN* IN SHORT PERIODS IN 1890... ... ... ... .. ... ... [ 99] HEAVY FALLS IN 24 HOURS IN 1890 ... ... ... ... .. ... ... ... [102] DROUGHTS IN 1890 ..