Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Practices in the Philippines: Meeting National and Global Targets JESAM at the Local Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Representatives

CONGRESS OF THE PHILIPPINES FIFTEENTH CONGRESS First Regular Session } . HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ,0. No. 4586 By REPRESENTATIVES ZAMORA-AP~AY AND ANGARA, PER COMMmEE REpORT No. 906 AN ACT ESTABLISHING A STATE COLLEGE IN THE MUNICIPALITY OF COMPOSTELA, PROVINCE OF COMPOSTELA V ALLEY TO BE KNOWN AS THE COMPOSTELA VALl·EY STATE COLLEGE, INTEGRATING THBRfiWITH /\8 REGULAk BRANCHES THE BUKlDNON STATE UNIVER~ITY EXTEIUIAL STUDIES CENTERS IN THE MUNICIPALITIES OF MONKAYO, MARAGUSAN, MONTEVISTA AND NEW BATAAN, ALL LOCATED IN THE PROVINCE OF COMPOSTELA VALLEY AND APPROPRIA rING FUNDS THEREFOR Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives ofthe Philippines i" Congress assembled: SECTION I.,Establishment. - There is hereby est.blished a state 2 college in the Municipality of Compostela, Province of Compostela Valley to j be known as the Compostela Valley State College, bereinafter referred to as 4 the College, and integrating therewith as its regular branches the Bukidnon 5 State University (BSU) External Studies Centers in the municipalities of 6 Monkayo, Maragusan, Montevista and New Bataan, all located in the Province 7 of Compostela Valley. The main campus shall be located in the Municipality 8 of Compostela. 2 SEC. 2. General Mandate. - The College shall primatily provide 2 advanced education, higher technological, professional instruction and trainhlg 3 in agriculture, science and technology and otber related fields: It shall &lso 4 undertake research and ex\'msion services in support of the socioeconomic 5 development of the Province of Compostela Valley and provide progressive 6 leadership in its areas of specialization. 7 SEC. 3. AcademIc Freedom and Institutional Autonomy. -

DAVAO CENTER for HEALTH DEVELOPMENT Os

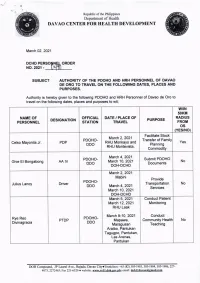

Republic of the Philippines /O" O\ Department of Health o DAVAO CENTER FOR HEALTH DEVELOPMENT Match 02,2021 DCHD PERSO N ORDER NO.202t - SUBJECT AUTHORITY OF THE POOHO AND HRH PERSONNEL OF DAVAO DE ORO TO TRAVEL ON THE FOLLOYUNG DATES, PLACES AND PURPOSES. Authority is hereby given to the following PDOHO and HRH Personnel of Davao de Oro to travel on the following dates, places and purposes to wit; wflN 50KU NATUIE OF OFFICIAL DATE / PLACE OF RADlUS DESIGNATION PURPOSE PERSONNEL STATION TRAVEL FROT os (YES/NO) Facilitate Stock March2,2021 PDOHO- Transfer of Family Celso Mayonila Jr. PDP RHU Monkayo and Yes DDO Planning RHU Montevista, Commodity March 4,2Q21 PDOHO- Submit PDOHO Ghie El Bongabong AA IV March 10, 2021 No DDO Documents DOH-DCHD March 2,2021 Mabini Provide PDOHO. Julius Lanoy Driver Transportation No DDO March 4,2021 Services March'10, 2021 DOH-DCHD March 5, 2021 Conduct Patient March 12,2021 Monitoring RHU Laak March 9-10, 2021 Conduct Rye Reo PDOHO- PTDP Mapawa, Community Health No Divinagracia DDO Maragusan Teaching Araibo, Pantukan Tagugpo, Pantukan, Las Arenas, Pantukan DOH Compound, JP laurel Ave., Bajada Davao City.Trunklines: +63 (E2) 305-1903, 305-1904, 305'1906,22'l- 4073,2272463iFu.221{320 o website: g44g4q[!!9[.ggy,p!; email: dg.b!149r!@4Ed!g, Republic of the Philippines .a" D. Department of Health .E:; o DAVAO CENTER FOR HEALTH DEVELOPIVTENT Conduct Technical Assistance regarding COVID 19 Reporting of Newly Hired PDOHO- March 9-10, 2021 Jason Mayang DSO Encoder No DDO RHU Maragusan Surveillance Functionality Assessment -

A Case Study on Indigenous Herbal Medicines

Ethnomedical documentation of and community health education for selected Philippine ethnolinguistic groups: the Mansaka people of Pantukan and Maragusan Valley, Compostela Valley Province, Mindanao, Philippines A collaborative project of Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care, Department of Health, Sta Cruz, Manila University of the Philippines Manila, Ermita, Manila University of the Philippines Mindanao, Bago Oshiro, Davao City 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive summary 1 Introduction 2 Objectives 3 Methodology 4 Results and discussion 7 Recommendations 21 References 22 Appendices 23 Tables Table 1. Materia medica Table 2. Mansaka terms Table 3. Mansaka demography ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We wish to acknowledge and express our heartfelt gratitude to the following people and organizations who have been significant partners in the undertaking of this research study: UP Mindanao Planning and Development Office for guidance and monitoring of the project; Mayor Jovito Derla and Municipal Assistant Administrator Mr Romeo Ang of Pantukan for permitting the research and helping in the selection of site; Mayor Gerome Lamparas of Maragusan Valley for permitting the research studies in the area; Barangay Captain Felicisimo C Marbones, Barangay Councilor and Matikadung Laurencio Camana of Barangay Napnapan for permitting the research to be conducted in Napnapan, Pantukan, Compostela Valley Province; Informants, contacts and guides from Maragusan and Pantukan communities for the support and unselfish sharing of their indigenous knowledge; Researcher’s family, friends and loved ones for their spiritual support through prayers for the safety during the one-year conduct of the research; and Above all, the Almighty God, to Whom all things were made possible. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An ethnopharmacological study of the Mansaka people in the municipalities of Pantukan and Maragusan Valley, Compostela Valley Province was conducted in June 1999 to May 2000. -

PHI-OCHA Logistics Map 04Dec2012

Philippines: TY Bopha (Pablo) Road Matrix l Mindanao Tubay Madrid Cortes 9°10'N Carmen Mindanao Cabadbaran City Lanuza Southern Philippines Tandag City l Region XIII Remedios T. Romualdez (Caraga) Magallanes Region X Region IX 9°N Tago ARMM Sibagat Region XI Carmen (Davao) l Bayabas Nasipit San Miguel l Butuan City Surigao Cagwait Region XII Magsaysay del Sur Buenavista l 8°50'N Agusan del Norte Marihatag Gingoog City l Bayugan City Misamis DAVAO CITY- BUTUAN ROAD Oriental Las Nieves San Agustin DAVAO CITY TAGUM CITY NABUNTURAN MONTEVISTA MONKAYO TRENTO SAN FRANS BUTUAN DAVAO CITY 60km/1hr Prosperidad TAGUM CITY 90km/2hr 30km/1hr NABUNTURAN MONTEVISTA 102km/2.5hr 42km/1.5hr 12km/15mns 8°40'N 120km/2.45hr 60km/1hr 30km/45mns. 18kms/15mns Claveria Lianga MONKAYO 142km/3hr 82km/2.5hr 52km/1.5hr 40km/1hr 22km/30mns Esperanza TRENTO SAN FRANCISCO 200km/4hr 140km/3 hr 110km/2.5hr 98km/2.hr 80km/1.45hr 58km/1.5hr BUTUAN 314km/6hr 254km/5hr 224km/4hr 212km/3.5hr 194km/3hr 172km/2.45hr 114km/2hr l Barobo l 8°30'N San Luis Hinatuan Agusan Tagbina del Sur San Francisco Talacogon Impasug-Ong Rosario 8°20'N La Paz l Malaybalay City l Bislig City Bunawan Loreto 8°10'N l DAVAO CITY TO - LORETO, AGUSAN DEL SUR ROAD DAVAO CITY TAGUM CITY NABUNTURAN TRENTO STA. JOSEFA VERUELA LORETO DAVAO CITY 60km/1hr Lingig TAGUM CITY Cabanglasan Trento 90km/2hr 30km/1hr NABUNTURAN Veruela Santa Josefa TRENTO 142km/3hr 82km/2.5hr 52km/1.5hr STA. -

Resignations and Appointments

N. 180407d Saturday 07.04.2018 Resignations and Appointments Resignation of bishop of Tagum, Philippines, and appointment of successor Resignation of President of Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts and appointment of new President Appointment of apostolic nuncio in Azerbaijan Appointment of eparchial bishop of Nyìregyháza Resignation of bishop of Tagum, Philippines, and appointment of successor The Holy Father has appointed as bishop of Tagum, Philippines, the Rev. Medel S. Aseo, of the clergy of the same diocese, currently missionary at the Saint Mary Parish, Pennsylvania, United States of America. Rev. Medel S. Aseo H.E. Msgr. Medel S. Aseo was born in Maniki, Kapaong, Davao del Norte, in the diocese of Tagum, on 27 June 1954. Following high school and courses in philosophy at the Saint Francis Xavier College Seminary in Davao City, he studied theology at the Saint Francis Xavier Regional major seminary of the same city. Subsequently, between 1988 and 1991, he carried out his postgraduate studies at the CEFAM Family Centre at the Loyola School of Theology of the Ateneo de Manila University. He was ordained a priest for the diocese of Tagum on 7 April 1979. During the years 1979-1980 he served as parish vicar at the Santo Niño parish in Panabo and, between 1980 and 1983, parish priest first in Manay and then Cateel in Davao Oriental. He was vice-rector and procurator at the Seminary College of Tagum, between 1983 and 1985, he was then Parish Priest in Maragusan, in the Davao 2 del Norte, between 1986 and 1988. Between 1988 and 1991 he attended the Loyola School of Theology for the aforementioned studies; then ending them, between 1996 and 1999. -

Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (Ra 8371) in 2019 Mindanao

“Forging partnership for rights-based development of the Indigenous Peoples” INDIGENOUS PEOPLES RIGHTS ACT (RA 8371) IN 2019 MINDANAO By: Atty. Ariel T. Montaňa June 11, 2019 #solidarityforIPdevelopment HISTORY When the Spaniards conquered the Philippines, they declared that!! All lands of the Philippines became the property of the King of Spain. (Regalian Doctrine) Impact of the legal system on the Indigenous Peoples When the Spaniards left, we continued to use their Government system; This did not recognize traditional land rights and ownership of ICCs/IPs; Without titles, Indigenous Peoples were forced to lose ownership of these lands. October 29, 1997 •Republic Act 8371 (Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997) became a law. LEGAL BASIS 1987 PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTION (e.g. Article II, Section 22, Article XVI, Section 12) INTERNATIONAL LAW (e.g. UNDRIP) JURISPRUDENCE [(e.g. Cariňo vs. Insular Government (212 US 449)] IPRA SALIENT FEATURES: 1. Right to Ancestral Domain 2. Right to Self-Governance and Empowerment 3. Social Justice and Human Rights 4. Cultural Integrity 5. Creation of NCIP 6. Quasi-Judicial Power Right to Self Governance and Empowerment Section 13 – The State recognizes the inherent right of the ICCs/IPs to self-governance and self- determination and respects the integrity of their values, practices and institutions. Right to Self Governance and Empowerment Customary Laws (Section 65) Tribal Barangays Mandatory Representation in policy making bodies and in local legislative bodies Social Justice and Human Rights Equal Protection -

Compostela Valley

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT XI #58 McArthur Highway, Matina, Davao City http://region11.dilg.gov.ph Province: COMPOSTELA VALLEY CITY/ PARTY TERM OF OFFICE MUNICIPALITY POSITION NAME OF OFFICIAL SEX AFFILIATION A. PROVINCE Member, House of Come-backing MANUEL E. ZAMORA M HNP Representative (1st District) Member, House of Re-elected (2nd Term) RUWEL PETER S. GONZAGA M HNP Representative (2nd District) Governor JAYVEE TYRON L. UY M HNP Re-elected (2nd Term) Vice-Governor MARIA CARMEN S. ZAMORA F HNP Newly Minted NENA G. ATAMOSA F HNP Re-elected (2nd Term) ADOLFO C. ANG M HNP Newly Minted Sangguniang Panlalawigan MARIE JUDE F. LOPOZ F HNP Re-elected (2nd Term) st Members (1 District) RENATO B. BASAÑES M HNP Re-elected (2nd Term) JOSEPH T. JAUOD M HNP Re-elected (3rd Term) ARTURO T. UY M HNP Re-elected (2nd Term) KRISTINE MAE T. CABALLERO- Re-elected (2nd Term) F HNP RAÑON MASTERLIST OF NEWLY ELECTED OFFICIALS 2019 Midterm Elections Sangguniang Panlalawigan RAUL B. CABALLERO M HNP Re-elected (2nd Term) Members (1st District) VIVENCIA L. SECUYA F HNP Re-elected (3rd Term) MACARIO T. HUMOL M HNP Re-elected (3rd Term) B. MUNICIPALITY Mayor LEMA P. BOLO, CPA F HNP Re-elected (3rd Term) COMPOSTELA Vice Mayor LEVI S. EBDAO M HNP Newly Minted RICKY P. HECHANOVA M INDEPENDENT Newly Minted WILFREDO C. ANG M HNP Re-elected (2nd Term) ALAN M. CALALAS M HNP Re-elected (2nd Term) REYNALDO Q. CASTILLO M HNP Newly Minted SB Members JURIC G. BLANCO M INDEPENDENT Come-backing DANIELO B. -

2010 Census of Population and Housing Compostela Valley

2010 Census of Population and Housing Compostela Valley Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population COMPOSTELA VALLEY 687,195 COMPOSTELA 81,934 Bagongon 1,946 Gabi 3,891 Lagab 2,586 Mangayon 4,403 Mapaca 2,082 Maparat 3,445 New Alegria 3,262 Ngan 7,738 Osmeña 4,753 Panansalan 906 Poblacion 26,773 San Jose 5,114 San Miguel 7,354 Siocon 3,266 Tamia 2,621 Aurora 1,794 LAAK (SAN VICENTE) 70,856 Aguinaldo 4,151 Banbanon 1,352 Binasbas 1,127 Cebulida 1,797 Il Papa 1,189 Kaligutan 2,902 Kapatagan 4,461 Kidawa 2,050 Kilagding 2,012 Kiokmay 1,379 Langtud 2,896 Longanapan 2,334 Naga 1,249 Laac (Pob.) 7,150 San Antonio 2,426 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Compostela Valley Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Amor Cruz 2,675 Ampawid 2,633 Andap 1,745 Anitap 505 Bagong Silang 1,063 Belmonte 1,212 Bullucan 1,229 Concepcion 1,114 Datu Ampunan 1,145 Datu Davao 1,031 Doña Josefa 894 El Katipunan 1,140 Imelda 1,996 Inacayan 1,077 Mabuhay 2,298 Macopa 707 Malinao 711 Mangloy 1,299 Melale 1,701 New Bethlehem 601 Panamoren 911 Sabud 1,211 Santa Emilia 1,438 Santo Niño 1,120 Sisimon 925 MABINI (DOÑA ALICIA) 36,807 Cadunan 3,988 Pindasan 5,524 Cuambog (Pob.) 6,016 Tagnanan (Mampising) 4,735 Anitapan 3,435 Cabuyuan 1,940 Del Pilar 2,054 Libodon 1,145 Golden Valley (Maraut) 5,061 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population -

Dtlyi'4m''{Rjfamhm.P'fi'gesoiii

Republic of the Philippines Department of Health REGIONAL OFFICE XI DOH Compound, JP Laurel Ave., Bajada, Davao City Trunklines: t63 (82) 305-1903, 305-l 904, 305-1906, 22'7 4073, 22'72463: F ax 221 -6320 email: [email protected] website: www.rol l.doh.gov.pb January I 2, 201 5 RO ORDER No. SUBJECT: AUTHORITY OF SOME DOH RO XI PERSONNEL TO TRAVEL TO COMVAL PROVINCE ON JANUARY 20-22 & 28-30.20T5 The following DOH RO Xl personnel are hereby authorized to travel to Compostela Valley Province on lanuary 20-22 & 28-30, 2015 to conducr the following, to wit: l. Engr. Divina B. Sonido - Engineer III (Jan.28-30,2015) 2. Archt. Alger G. Salazar - Architect II (lan.20-22 &28-30,2015) 3. Engr. Tote M. Similatan - Engineer I (Iaul..20-22 & 28-30,2015) 4. Ezra Wayland D. Callao - Elect'l Eng'g Asst. (Jan. 28-30, 2015) 5. Reynaldo F. Alarcon - Engineer lV (Jan.22,2015 only) 6. Mohammad Fahrudin M. Aliuden - LO II (Jan.22,2015 only) Places to be visited: January 20, 2015 Ngan BHS-Compostela, Comval Province January 21, 2015 Bawani BHS & Tuboran BHS, Mawab, Comval Province January 22,2015 Laak RHU, Comval Province January 28,2015 Laak CVPH, Laak RHU, Comval Province lanuary 29,2015 Maragusan CVPH, Maragusan RHU, Comval Province January 30,2015 Montevista CVPH, Montevista RHU, Comval Province a. Conduct final inspection together with the HFEP Inspectorate Team for Laak RHU 2014 Project. b. Conduct pre-construction meeting with the end-user & contractor for the newly awarded CVPH Projects under HFEP 2014 (La k, Maragusan & Montevista, Comval province) and BHS Projects under AECID & EU Grant (BHS Ngan-Compostela, BHS Bawani & BHS Tuboran, Mawab, ComVal Province). -

Cy 2018 List Small Enterprise Technology Upgrading Program

CY 2018 LIST SMALL ENTERPRISE TECHNOLOGY UPGRADING PROGRAM Project Title Project Beneficiary Brief Description Location District Project Cost Productivity Upgrading of CPR Gun CPR Gun Technology Inc., The project aims to improve the efficiency and productivity on Brgy. Vicente, Hizon, Davao I 3,000,000.00 Technology, Inc. gunsmithing services of CPR Gun Technology, Inc. and expand product City lines to cater to market demand. Equipment Upgrading of Benjo Benjo Machine Shop The project aims to increase the capacity of the firm thru the provision Buhangin, Davao City II 500,000.00 Machining Services of upgraded machining facility. Technology Upgrading of Calixtra Calixtra’s Food Products The project intends to provide efficient and GMP-compliant equipment Buhangin, Davao City II 2,500,000.00 Meat Processing and tools to increase the firm's productivity and improve the quality of processed meat. Quality and Packaging Enhancement Davao Mission Foods The assistance will involve the provision of efficient food processing and Palm Drive, Buhangin, Davao II 1,200,000.00 of Davao Mission Foods packaging equipment to improve the marketability of soya products. City Production Upgrading of B & N Boy & Nida Food Products The project aims to provide efficient equipment and tools to extend the NCCC Village, Brgy. 20-B, I 500,000.00 Processed Meats product shelf-life and improve the quality of processed meat. Davao City Productivity Improvement of Bio Leaf Bio Leaf RM Enterprise This objective of the project is to improve the firm's productivity thru Ma-a, Davao City I 1,000,000.00 Herbal Soap the provision of mechanized processing and packaging machines for herbal soap production. -

Tier 1 Agency: Department of Public Works and Highways XI

Tier 1 Agency: Department of Public Works and Highways XI 58,885,562 0.00 BRIEF PROGRAM/PROJECT DESCRIPTION SPATIAL COVERAGE RDP RESULTS MATRIX (RM) SOURCE OF UACS PROGRAMS/ACTIVITIES/PROJECTS CONGRESSIONAL COST (PHP'000) REMARKS Scope of Work Physical Target PROVINCE INDICATOR ADDRESSED FUNDS DISTRICT - Continuing projects Compostela Valley, 1st Congressional District Compostela Valley 1st District 3,829,614 GAA MFO I: National Road Network Services 2,636,774 I. National Roads : 901,449 A. Primary Roads 369,159 - Daang Maharlika 369,159 - Widening (into 6 lanes) including Drainage and 3.954 km Monkayo and Montevista Increased length of national 170,660 RROW roads widened 0.666 km K1377+ -201-K1377+465 28,640 3.122 km K1377+883-K1381+000 131,880 0.166 km K1410+158-K1410+324 10,140 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Paving of 9.296 km Montevista and Monkayo Increased length of off- 97,739 shoulder with Construction of Median and Laybys 0.178 km K1393+022-K1393+200 carriageway along national 1,801 1.149 km K1393+200-K1394+400 roads improved/constructed 10,171 (includes pedestrian overpass @ K1394+660 ) 0.374 km K1394+400-K1394+774 21,790 2.472 km K1410+031-K1412+500 19,124 0.181 km K1412+500-K1412+681 1,815 0.099 km K1412+702-K1412+801 1,246 0.360 km K1412+801-K1413+160 6,620 0.290 km K1413+160-K1413+450 6,305 4.193 km K1413+450-K1417+629 28,869 - Rehabilitation/reconstruction/ upgrading of 1.242 km Monkayo Increase length of damaged 37,260 damaged paved road 0.110 km K1382+027-K1382+137 paved road 3,300 0.200 km K1382+308-K1382+508 rehabilitated/reconstructed/ -

Pdf | 425.17 Kb

Areas Having Public Storm Warning Signal PSWS # Luzon Visayas Mindanao Signal No. 1 None None Surigao del Sur (30-60 kph winds Agusan del Sur may be expected Davao Oriental in at least 36 Davao del Norte hours) Davao del Sur Compostella Valley • Estimated rainfall amount is from 5 - 15 mm per hour (moderate - heavy) within the 300 km diameter of the Tropical Depression. • Tropical Depression "AGATON" is expected to bring moderate to occasionally heavy rains and thunderstorms over the rest of Visayas. • Sea travel is risky over the seaboards of Luzon and Visayas. • The public and the disaster risk reduction and management councils concerned are advised to take appropriate actions II. EFFECTS A. INCIDENTS MONITORED (TAB A) • A total of twenty-four (24) incidents were reported; sixteen (16) landslide incidents, six (6) floodings/flashflood incidents and two (2) maritime incidents in Regions VIII, IX, X, XI, CARAGA and ARMM B. CASUALTIES (TAB B) • A total of forty (40) persons were reported dead, sixty-five (65) are injured and five (5) are still missing in Regions IX, X, XI and CARAGA C. AFFECTED POPULATION (TAB C) • A total of 140,423 families/667,353 persons were affected in 700 barangays in 98 municipalities in 15 provinces of Regions X, XI, CARAGA and ARMM • Out of the total affected, 26,815 families / 129,123 persons were displaced and served inside 394 evacuation centers D. STATUS OF STRANDEES (as of 12:00 NN, 19 January 2014) ROLLING STRANDED PASSENGERS VESSELS MBCA’s CARGOES CGDCV CGS Cebu 771 26 43 05 CGS Dumaguete 07 03 CGS Tagbilaran 04 01 CGDEV CGS Maasin 318 40 CGS Ormoc 70 05 24 CGDBCL CGS Cam Sur 180 CGS Sorsogon 3,770 379 02 CGS Masbate 29 02 2 CGDNM CGS Surigao 368 05 50 16 TOTAL 5,506 49 536 27 E.