Chhaupadi Pratha: Women's Condition and Suffering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traversing the Ridge: Connecting Menstrual Research and Advocacy

23rd Biennial Conference of the Society for Menstrual Cycle Research Traversing the Ridge: Connecting Menstrual Research and Advocacy Colorado Springs, CO June 6 - 8, 2019 Full Conference Schedule & Abstracts: Thursday 6th June 2:00 pm Bemis Lounge Registrations Opens 3:00 pm – 4:30 pm Tutt Science Bldg (TSB) Concurrent Workshop (CW) Sessions #1 CW 1.1: How to Teach Cervical Mucus in Menstrual Health Education TSB Rm. 218 Lisa Leger, Justisse College International, Canada Sexual health education teaches about menstruation, contraception, and STI’s, but usually lacks a coherent strategy for teaching about cervical mucus and other symptoms that the cycling body experiences. This session is intended as training on how to teach about the meaning and usefulness of cervical mucus observations so your clients get a more full picture about what occurs in the female body and how to interpret their observations. Justisse Holistic Reproductive Health Practitioners will explain how to talk about vaginal fluids to reassure clients that it is something normal, healthy, and actually useful to be aware of. This session will review how to handle questions about what clients see in their underwear or on the toilet tissue and the pros and cons of internal checks. You will learn how to field such questions and use them as teachable moments to elaborate on how Fertility Awareness Methods work, the benefits of being aware of cycles, and how such observations can be used as a health record and diagnostic tool. Learn how to explain the ways in which cervical mucus differs from vaginal cell slough, yeast infection, Bacterial Vaginosis, or arousal fluid. -

Nepal's Menstrual Movement

Implemented by: In Cooperation with: NEPAL’S MENSTRUAL MOVEMENT How ‘MenstruAction’ is making life better for girls and women in Nepal — month after month 1 FOREWORD ROLAND SCHÄFER, GERMAN AMBASSADOR TO NEPAL 03 FOREWORD DR. PUSHPA CHAUDHARY 05 FOREWORD DR. MARNI SOMMER 06 INTRODUCTION 07 THE ANCIENT PRACTICE OF CHHAUPADI 08 THE SCALE OF THE PROBLEM: SOME FACTS AND FIGURES 10 Content Practice of Chhaupadi 11 Menstruation product access and usage 11 Other restrictions 12 Sanitation 13 THE STORY SO FAR 14 Right to informed choice 17 Moving the MHM agenda forward 18 Working together through the MHM Practitioner Alliance 19 MENSTRUACTIVISTS. SOME MOVERS AND SHAKERS BEHIND MHM 20 MHM is the biggest topic around 21 The need for better data and understanding of the issues 23 Reflecting on restrictive practices through film making 25 Five Days 27 WATER AND SANITATION. THE KEY TO BETTER MENSTRUAL HYGIENE 28 Nepal’s geography is the biggest challenge 29 Addressing menstrual issues through WASH programmes 31 EDUCATION TO TACKLE TABOOS 32 The government is incorporating MHM issues into the school curriculum 33 AWARENESS AND EDUCATION IN ACTION: THE EXAMPLE OF BIDUR MUNICIPALITY 34 Raising awareness about menstrual health and hygiene management 35 Allocating resources to schools for MHM 36 Working with young people 38 Using radio to break down taboos 39 INVENTIONS, INNOVATIONS AND SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS 40 Producing low cost sanitary pads 41 Homemade eco-friendly, reusable cloth sanitary pads 42 ‘Wake Up, Kick Ass’ 43 Nepal’s first sanitary napkin -

Adolescent Menstrual Health Literacy in Low, Middle and High-Income Countries: a Narrative Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Adolescent Menstrual Health Literacy in Low, Middle and High-Income Countries: A Narrative Review Kathryn Holmes 1,* , Christina Curry 1, Sherry 1 , Tania Ferfolja 1, Kelly Parry 2, Caroline Smith 2,3, Mikayla Hyman 2 and Mike Armour 2,3 1 Centre for Educational Research, Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (S.); [email protected] (T.F.) 2 NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia; [email protected] (K.P.); [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (M.A.) 3 Translational Health Research Institute (THRI), Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64247360252 Abstract: Background: Poor menstrual health literacy impacts adolescents’ quality of life and health outcomes across the world. The aim of this systematic review was to identify concerns about menstrual health literacy in low/middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries (HICs). Methods: Relevant social science and medical databases were searched for peer-reviewed papers published from January 2008 to January 2020, leading to the identification of 61 relevant studies. Results: A thematic analysis of the data revealed that LMICs report detrimental impacts on Citation: Holmes, K.; Curry, C.; adolescents in relation to menstrual hygiene and cultural issues, while in HICs, issues related to pain Sherry; Ferfolja, T.; Parry, K.; Smith, C.; Hyman, M.; Armour, M. -

Field Bulletin

Issue No.: 01; April 2011 United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office FIELD BULLETIN Chaupadi In The Far-West Background Chaupadi is a long held and widespread practice in the Far and Mid Western Regions of Nepal among all castes and groups of Hindus. According to the practice, women are considered ‘impure’ during their menstruation cycle, and are subsequently separated from others in many spheres of normal, daily life. The system is also known as ‘chhue’ or ‘bahirhunu’ in Dadeldhura, Baitadi and Darchula, as ‘chaupadi’ in Achham, and as ‘chaukulla’ or ‘chaukudi’ in Bajhang district. Participants of training on Chaupadi-WCDO Doti Discrimination Against Women During Menstruation According to the Accham Women’s Development Officer (WDO), more Women face various discriminatory practices in the context of than 95% of women are practicing chaupadi. The tradition is that women cannot enter inside houses, chaupadi in the district. Women kitchens and temples. They also can’t touch other persons, cattle, and Child Development Offices in green vegetables and plants, or fruits. Similarly, women practicing Doti and Achham are chaupadi cannot milk buffalos or cows, and are not allowed to drink implementing an ‘Awareness milk or eat milk products. Programme against Chaupadi’. The programme is supported by Save Generally, women stay in a separate hut or cattle shed for 5 days the Children and covers 19 VDCs in during menstruation. However, those experiencing menstruation for Achham and 10 VDCs in Doti.In the the first time should, according to practice, remain in such a shed for VDCs targeted by this program, the at least 14 days. -

GSF), Which Since 2008 Has Committed Over $117 Million to Transform Lives in Developing Countries

RESEARCH STUDY Scoping and Diagnosis of the Global Sanitation Fund’s Approach GLOBAL SANITATION FUND SANITATION GLOBAL to Equality and Non-Discrimination Authors: Dr. Sarah House, Suzanne Ferron, Dr. Sue Cavill With contributions from Dr. Jacques-Edouard Tiberghien, Partnerships in Practice | SCOPING AND DIAGNOSIS OF THE GLOBAL SANITATION FUND’S APPROACH TO EQUALITY AND NON-DISCRIMINATION EQUALITY TO APPROACH FUND’S SANITATION OF THE GLOBAL SCOPING AND DIAGNOSIS About WSSCC The Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) is at the heart of the global movement to improve sanitation and hygiene, so that all people can enjoy healthy and productive lives. Established in 1990, WSSCC is the only United Nations body devoted solely to the sanitation needs of the most vulnerable and marginalized people. In collaboration with our members in 141 countries, WSSCC advocates for the billions of people worldwide who lack access to good sanitation, shares solutions that empower communities, and operates the Global Sanitation Fund (GSF), which since 2008 has committed over $117 million to transform lives in developing countries. About GSF GSF invests in collective behaviour change approaches that enable large numbers of people in developing countries to improve their access to sanitation and adopt good hygiene practices. Established in 2008 by WSSCC, GSF is the only global fund solely dedicated to sanitation and hygiene. WSSCC gratefully acknowledges the donors that, through its lifetime, have made GSF’s work possible: the Governments of Australia, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Front cover photos (from top): Senegal: Adolescent girls discuss their sanitation needs. ©Suzanne Ferron Nepal: A Dalit woman and her daughter display their improved latrine. -

'Let's Talk Period'

‘LET’S TALK PERIOD’ Authored by: Dr. Deepali Bhardwaj, Surbhi Guleria ,Hifza Rehman and Shalini Maji It is rightly said that you can’t end racism and inequality without addressing sexism. We claim to be free of all biasis and treat everyone equally without any prejudices but the on ground reality is that even in this 21st century , both men and women are not equal. Feminist movements have made a gigantic strides over the years but the word “FEMINISM” still remains a controversial one.Women are still looked down upon and are considered to the inferior sex in comparision to men. According to the Human Rights Commision ,“the widespread stigma and shame surrounding menstruation and menstrual hygiene by ensuring access to factual information thereon, addressing the negative social norms around the issue and ensuring universal access to hygienic products and gender-sensitive facilities, including disposal options for menstrual products.” MENSTRUATION is an inevitable part of a female’s life but sadly rather than considering it to be only as a biological function it is often perceived another basis for gender discrimination. The first period can be meet with either celebration , fear or concern. For every girl ,this signifies an important transition to womanhood. In this time they need support but what they get is shame and exclusion. Women’s experience during menstruation differ greatly depending on which area of the world they are living in. It’s significance varies substantially among different cultures and religious groups and socio economic status. Developed countries tend to have a wider availibality of feminine hygiene products such as tampons ,menstrual cups , pads and panty liners unlike developing nations even in 2018. -

A Visual, Community-Engaged Exploration of Menstrual Practices and Motivations Among

Title Page A Visual, Community-Engaged Exploration of Menstrual Practices and Motivations Among Adolescent Girls in Far-West Nepal by Sara Elizabeth Baumann BA in Sociology of Health & Aging, Minor in Peace & Social Justice, University of Michigan, 2008 MPH, BRAC University, Bangladesh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences Graduate School of Public Health in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 Committee Membership Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH This dissertation was presented by Sara Elizabeth Baumann It was defended on July 18, 2019 and approved by Shalini R. Ayyagari, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Music Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pittsburgh Müge Kökten Finkel, PhD, MA, Assistant Professor Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, University of Pittsburgh Marni Sommer, DrPH, MSN, RN, Associate Professor, Sociomedical Sciences Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York Martha Ann Terry, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Advisor: Jessica G. Burke, PhD, MHS, Professor, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © 2019 Sara Elizabeth Baumann. All Rights Reserved. iii A Visual, Community-Engaged Exploration of Menstrual Practices and Motivations Among Adolescent Girls in Far-West Nepal Sara Elizabeth Baumann, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 Abstract Menstrual health, a growing global public health issue, refers to social, political, structural, educational and environmental factors that affect experiences of menstruation and impact health. -

She Got Her Period: Men's Knowledge and Perspectives on Menstruation

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects Capstone Projects 2015 She Got Her Period: Men's Knowledge and Perspectives on Menstruation Ishwari Rajak Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Health Communication Commons, and the Women's Health Commons Recommended Citation Rajak, I. (2015). She Got Her Period: Men's Knowledge and Perspectives on Menstruation [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/429/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Running head: SHE GOT HER PERIOD: MEN’S KNOWLEDGE AND PERSPECTIVES ON MENSTRUATION She Got Her Period: Men’s Knowledge and Perspectives on Menstruation By Ishwari Rajak A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Gender and Women’s Studies Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota May 2015 She Got Her Period: Men’s Knowledge and Perspectives on Menstruation Ishwari Rajak This thesis has been examined and approved by the following members of the student’s committee. -

Menstruation Matters! Wateraid/Mani Karmacharya Wateraid/Mani

Menstruation Matters! WaterAid/Mani Karmacharya WaterAid/Mani This brief aims to support policy and Every woman and girl decision makers to take adequate steps to ensure all women and girls have the deserves the right to right to manage their periods safely and in a dignifed way. It unpacks the socio- manage their period in a economic implications of menstruation safe and dignifed way. and acknowledges progress made so far in addressing challenges to menstrual hygiene management in Nepal. It makes policy recommendations with the objective of lessening on-going gaps in policies and practices governing menstrual hygiene management and calls for a comprehensive national policy on safe and dignifed menstruation with a framework guided by a human rights approach. MHM POLICY BRIEF WaterAid/ Poulomi Basu WaterAid/ Menstruation matters not only to girls and women but also to society and economy at large. Indications across the world reveal multiple and diverse barriers faced by adolescent girls and women while managing their menstrual cycle. These barriers have implications on the physical, emotional and psychological well- being, education, employment, livelihoods and participation of adolescent girls and women in the economy thus making signifcant impact on a country’s development. The socio cultural Context practices that govern communities have implications on individuals’ attitudes, beliefs and behaviours towards menstruation. Taboos and stigma associated with menstruation poses as a hindrance to the adolescent girls and women and can result in the denial of their human rights. 2 MHM POLICY BRIEF Access to basic facilities for menstrual hygiene management (MHM) is critically important for women’s health, safety and dignity. -

Menstrual Hygiene Management Practices

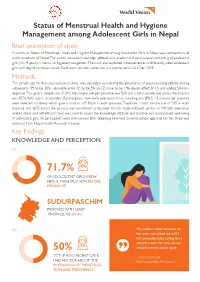

Status of Menstrual Health and Hygiene Management among Adolescent Girls in Nepal Brief description of study A survey on Status of Menstrual Health and Hygiene Management among Adolescent Girls in Nepal was conducted in all seven provinces of Nepal. The survey assessed knowledge, attitude and practice and psychosocial well-being of adolescent girls (10-19 years) in menstrual hygiene management. The study also explored the experiences of differently abled adolescent girls with regard to menstruation. Field work and data collection was conducted in Oct-Dec 2019. Methods The sample size for this cross-sectional survey was calculated considering the prevalence of psychosocial problems among adolescents (P) to be 30%, allowable error (L) to be 5% and Z value to be 1.96, design effect of 1.5 and adding 5% non- response. This gave a sample size of 340, the sample size per province was 510 and a total sample size across the country was 3570. With a plan to consider 35 participants from each selected primary sampling unit (PSU). 15 schools per province were selected randomly which gave a total of 105 PSUs in each province. Therefore, a total sample size of 525 in each province and 3675 across the country was considered to be taken for this study. Adopted version of MR-SSS (menstrual related stress and self-efficacy) tool was used to assess the knowledge, attitude and practice and psychosocial well-being of adolescent girls. All participants were interviewed after obtaining informed consent. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Nepal Health Research Council. Key Findings KNOWLEDGE AND PERCEPTION 01 71.7% OF ADOLESCENT GIRLS KNEW ABOUT MENSTRUATION BEFORE MENARCHE SUDURPASCHIM PROVINCE WITH LEAST KNOWLEDGE (47.4%) 02 My mother came to know on her own and asked me, still I felt uncomfortable telling her. -

Perception and Practices of Menstruation Restrictions Among

Mukherjee et al. Reproductive Health (2020) 17:81 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00935-6 RESEARCH Open Access Perception and practices of menstruation restrictions among urban adolescent girls and women in Nepal: a cross-sectional survey Amrita Mukherjee1, Mingma Lama2, Uddhav Khakurel2, Alok Nath Jha2, Fatima Ajose3, Sanjeev Acharya4, Kristina Tymes-Wilbekin1, Marni Sommer5, Pauline E. Jolly1, Pema Lhaki2* and Sadeep Shrestha1 Abstract Background: Menstruation, a natural biologic process is associated with restrictions and superstitious beliefs in Nepal. However, factual data on women’s perspectives on menstrual practices and restrictions are scarce. This study aimed to assess socio-cultural perceptions of menstrual restrictions among urban Nepalese women in the Kathmandu valley. Methods: Using a clustered random sampling, 1342 adolescent girls and women of menstruating age (≥15 years) from three urban districts in the Kathmandu valley completed a survey related to menstrual practices and restriction. This was a cross-sectional survey study using a customized program allowing pull-down, multiple choice and open-ended questions in the Nepali language. The self-administered questionnaire consisted of 13 demographic questions and 22 questions related to menstruation, menstrual hygiene, socio-cultural taboos, beliefs and practices. Univariate descriptive statistics were reported. Unadjusted associations of socio-cultural practices with ethnicity, education, four major social classes, three major religions, marital status and family type were assessed using logistic regression models. Results: More than half (59%) of the participants were aged between 15- < 25 years. The majority were Hindus (84.5%), reported not praying during menstruation (83.1%) and were encouraged by their mothers (72.1%) to practice a range of menstrual restrictions. -

First Blood: a Cultural Study of Menarche

First Blood First Blood A Cultural Study of Menarche Sally Dammery First Blood: A Cultural Study of Menarche © Copyright 2016 Sally Dammery All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/fb-9781925377040.html Series: Cultural Studies Design: Les Thomas ISBN: 9781925377040 (paperback) ISBN: 9781925377057 (PDF) ISBN: 9781876924829 (ePub) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Creator: Dammery, Sally, author. Title: First blood: a cultural study of menarche / Sally Dammery. ISBN: 9781925377040 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Menarche. Menstruation--Cross-cultural studies. Menstruation--Folklore. Menstruation--Religious aspects. Dewey Number: 305.4 CONTENTS About the Author .........................................vi Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Introduction .............................................ix Chapter 1 Of