Route to Rhodesia”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Beginner's Guide to Boating on Inland Waterways

Ti r A Beginner’s Guide To Boating On Inland Waterways Take to the water with British Waterways and the National Rivers Authority With well over 4,000 km (2,500 miles) of rivers and canals to explore, from the south west of England up to Scotland, our inland waterways offer plenty of variety for both the casual boater and the dedicated enthusiast. If you have ever experienced the pleasures of 'messing about on boats', you will know what a wealth of scenery and heritage inland waterways open up to us, and the unique perspective they provide. Boating is fun and easy. This pack is designed to help you get afloat if you are thinking about buying a boat. Amongst other useful information, it includes details of: Navigation Authorities British Waterways (BW) and the National Rivers Authority (NRA), which is to become part of the new Environment Agency for England and Wales on 1 April 1996, manage most of our navigable rivers and canals. We are responsible for maintaining the waterways and locks, providing services for boaters and we licence and manage boats. There are more than 20 smaller navigation authorities across the country. We have included information on some of these smaller organisations. Licences and Moorings We tell you everything you need to know from, how to apply for a licence to how to find a permanent mooring or simply a place for «* ^ V.’j provide some useful hints on buying a boat, includi r, ...V; 'r 1 builders, loans, insurance and the Boat Safety Sch:: EKVIRONMENT AGENCY Useful addresses A detailed list of useful organisations and contacts :: : n a t io n a l libra ry'& ■ suggested some books we think will help you get t information service Happy boating! s o u t h e r n r e g i o n Guildbourne House, Chatsworth Road, W orthing, West Sussex BN 11 1LD ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 1 Owning a Boat Buying a Boat With such a vast.range of boats available to suit every price range, . -

The Monthly Newsletter Published by the AUGUST 2020

AUGUST 2020 The monthly newsletter published by the Near the “Dirty Duck” Pub Photographed by Tony Osbond Please note that all images in this document are the copyright of either the photographer or The Grantham Canal Society. This month’s update from Mike Stone (Chairman) Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho, It's back to work we go All dressed in our own PPE with CRT life vest. The grass grows even higher, the locks are leaking too. Weeds stopped the trip-boat moving; we didn’t know what to do Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho We dig up stuff on Fridays we lift out branches too, We’re getting a new weed boat soon but drivers needed too As volunteers on this canal there’s so much work to do Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho, It's back to work we go .... Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho! Don’t just sing alone – come and join us - Heigh-ho! Heigh-ho! (No height restriction!) Thanks to you, our supporters, we have achieved our target to raise £20,000 to enable the restoration of the slipway at the Depot. This is a brilliant result in four months and the Society says a big THANK YOU to all who contributed. Restoration work will commence early in October – Heigh-ho! Within the coming week we look forward to the delivery of a new, to us, weed-boat from The Rothen Group. Which, by the way, hasn't been named yet - see p10. This will enable us to remove the extensive weed growth from the navigation and, I hope, permit The Three Shires charter cruises to re-commence operation. -

Better Towpaths for Everyone a National Policy for Sharing Towpaths Foreword Contents the Canal & River Trust Wants People to Enjoy the Waterways Within Its Care

Better Towpaths for Everyone A national policy for sharing towpaths Foreword Contents The Canal & River Trust wants people to enjoy the waterways within its care. Foreword 2 We want to encourage a diverse range of people to use, enjoy and cherish our canals and river navigations. Introduction 3 Consultation 3 Towpaths were built originally to support the use of boats on the water, and they remain essential for boating and other water-based activities such as Principles of angling, canoeing and rowing. They all need to use the towpaths for access towpath use 4 to the water, including for mooring up, or the operation of structures like locks and moveable bridges. Others enjoy the towpaths themselves – Better infrastructure 5 for walking, running and cycling, or simply to experience the calm, tranquil Towpath Design Guide 5 environment away from the bustle of everyday life. Better signs 6 Given the wide range of uses, and the millions of people who visit, we ask that people are considerate to others and in particular the slower, static or Better behaviour 7 more vulnerable users when they are on our towpaths. We do of course Towpath Code 7 recognise that some of our towpaths are busier than others; in some Activities 7 locations we know that conflict can occur, sometimes because an individual has wrongly assumed that they have priority over another, or because they don’t appreciate or respect other users. Sadly this detracts from people’s enjoyment, and we are committed to encouraging better behaviour by everyone on our towpaths, so that people can feel safe and secure when they use them. -

Waterway Dimensions

Generated by waterscape.com Dimension Data The data published in this documentis British Waterways’ estimate of the dimensions of our waterways based upon local knowledge and expertise. Whilst British Waterways anticipates that this data is reasonably accurate, we cannot guarantee its precision. Therefore, this data should only be used as a helpful guide and you should always use your own judgement taking into account local circumstances at any particular time. Aire & Calder Navigation Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Bulholme Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 6.3m 2.74m - - 20.67ft 8.99ft - Castleford Lock is limiting due to the curvature of the lock chamber. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Castleford Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom 61m - - - 200.13ft - - - Heck Road Bridge is now lower than Stubbs Bridge (investigations underway), which was previously limiting. A height of 3.6m at Heck should be seen as maximum at the crown during normal water level. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Heck Road Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.71m - - - 12.17ft - 1 - Generated by waterscape.com Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Leeds Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.5m 2.68m - - 18.04ft 8.79ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Crown Point Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.62m - - - 11.88ft Crown Point Bridge at summer levels Wakefield Branch - Broadreach Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.55m 2.7m - - 18.21ft 8.86ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. -

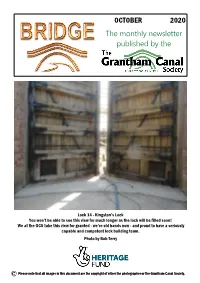

The Monthly Newsletter Published by the OCTOBER

OCTOBER 2020 The monthly newsletter published by the Lock 14 - Kingston’s Lock You won’t be able to see this view for much longer as the lock will be filled soon! We at the GCS take this view for granted - we’re old hands now - and proud to have a seriously capable and competent lock building team. Photo by Bob Terry Please note that all images in this document are the copyright of either the photographer or The Grantham Canal Society. This month’s update from Mike Stone (Chairman) We now commence a busy period on By the time you read this the water the Grantham when the flying wildlife might be trickling into Lock 14 now has ceased nesting. Jobs that are that the lads from CRT have installed planned include: re-constructing the both sets of gates. We should thank slipway at the depot; several specific them all for their skill and expertise issues at locks 16 to 18; continuing to and we hope the gates serve the lock clear the canal of hazards (weeds and for many years to come. other things) and establish the depth Those of you who purchased memorial of water between Lock 18 and the A1; bricks will be pleased to know that raising the level of Denton runoff weir; they have been erected in the form of examining the non-navigable canal for a bench seat at Lock 15. We had blockages and leaks that cause hoped to invite all to an opening event potential water loss; keeping fingers but unfortunately Covid-18 has once crossed awaiting the outcome of more interfered. -

Motorcycles on Towpaths (British Waterways and the Fieldfare Trust)

abc MOTORCYCLES ON TOWPATHS: Guidance on managing the problem and improving access for all June 2006 1 CONTENTS Page Preface 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Some existing solutions 6 3. Decision Flowchart 8 4. Recording and assessing the motorcycle problem 9 5. Management responses other than physical access controls 11 6. Access controls; selecting the appropriate design 13 7. Record, monitor and review 16 8. The importance of consultation 17 9. The impacts of various designs on both motorcycles and disabled users 18 Appendices Appendix 1: Further information 22 Appendix 2: Review of some current access controls 23 Appendix 3: Summary of accessibility issues for users with disabilities 26 Appendix 4: Mobility vehicles and recreational use 27 2 PREFACE This Guidance is an adaptation from internal guidance produced for British Waterways staff. It originates from a project commissioned from the Fieldfare Trust by BW. Its prime purpose is to suggest ways of dealing with the problems posed by unauthorised use of towpaths by motorcycles whilst trying to ensure the best access for legitimate users. BW recognises that the common response of erecting some type of obstacle or barrier too often hinders or presents legitimate access, particularly for disabled people. The Guidance relates particularly to towpaths and the waterway network but has wider application. BW is aware that many other land owners and managers have to deal with the problem of illegal motorcycle use and the nuisance, damage and risk that it causes and is pleased to share this Guidance in the belief that it will be useful to others. BW would welcome any feedback on its content and usefulness. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2005-06

CONTACT DETAILS WATERWAYS BRITISH Head Office Customer Service Centre Willow Grange, Church Road, Willow Grange, Church Road, Watford WD17 4QA Watford WD17 4QA T 01923 226422 T 01923 201120 ANNUAL REPORT & F 01923 201400 F 01923 201300 PUBLIC BENEFITS [email protected] FROM HISTORIC WATERWAYS BW Scotland Northern Waterways Southern Waterways British Waterways ACCOUNTS 2005/06 Canal House, Willow Grange ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2005/06 Applecross Street, North West Waterways Central Shires Waterways Church Road Glasgow G4 9SP Waterside House, Waterside Drive, Peel’s Wharf, Lichfield Street, Watford T 0141 332 6936 Wigan WN3 5AZ Fazeley, Tamworth B78 3QZ WD17 4QA F 0141 331 1688 T 01942 405700 T 01827 252000 enquiries.scotland@ F 01942 405710 F 01827 288071 britishwaterways.co.uk enquiries.northwest@ enquiries.centralshires@ T +44 1923 201120 britishwaterways.co.uk britishwaterways.co.uk F +44 1923 201300 BW London E [email protected] 1 Sheldon Square, Yorkshire Waterways South West Waterways www.britishwaterways.co.uk Paddington Central, Fearns Wharf, Neptune Street, Harbour House, West Quay, www.waterscape.com, your online guide London W2 6TT Leeds LS9 8PB The Docks, Gloucester GL1 2LG to Britain’s canals, rivers and lakes. T 020 7985 7200 T 0113 281 6800 T 01452 318000 F 020 7985 7201 F 0113 281 6886 F 01452 318076 ISBN 0 903218 28 3 enquiries.london@ enquiries.yorkshire@ enquiries.southwest@ Designed by 55 Design Ltd britishwaterways.co.uk britishwaterways.co.uk britishwaterways.co.uk Printed by Taylor -

British Waterways Board General Canal Bye-Laws

BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD GENERAL CANAL BYE-LAWS 1965 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD BYE-LAWS ____________________ for regulation of the canals belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board (other than the canals specified in Bye-law 1) made pursuant to the powers of the British Transport Commission Act, 1954. (N.B. – The sub-headings and marginal notes do not form part of these Bye-laws). Application of Bye-laws Application of 1. These Bye-laws shall apply to every canal or inland navigation in Bye-Laws England and Wales belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board except the following canals: - (a) The Lee and Stort Navigation (b) the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal (c) the River Severn Navigation which are more particularly defined in the Schedule hereto. Provided that where the provisions of any of these Bye-laws are limited by such Bye-law to any particular canal or locality then such Bye-law shall apply only to such canal or locality to which it is so limited. These Bye-laws shall come into operation at the expiration of twenty-eight days after their confirmation by the Minister of Transport as from which date all existing Bye-laws applicable to the canals and inland navigations to which these Bye-laws apply (other than those made under the Explosives Act 1875, and the Petroleum (Consolidation) Act 1928) shall cease to have effect, without prejudice to the validity of anything done thereunder or to any liability incurred in respect of any act or omission before the date of coming into operation of these Bye-laws. -

English Nature Research Report 75

4 CANALS AS AQUATIC CORRIDORS 4.1 INTRODUCTION The term 'corridor' can be used to describe two different situations. In the first, the corridor is simply a passage along which organisms travel. or along which propagules are dispersed. Thus, one can imagine a butterfly or a bird passing from one wood to another along a hedge, or a seed floating along a stream from one lake to another. The second situation is the corridor as a linear habitat in which organisms live and reproduce. This section of the report considers British canals as linear habitats for submerged and floating vascular plants. A study of the plants which have colonized canals is of interest for two reasons. Canals are of intrinsic importance, as they contain significant populations of many scarce or rare aquatic macrophytes. They are unstable habitats: if neglected they gradually become overgrown by emergent vegetation but if maintained and intensively used by boat traffic they also lose much of their botanical diversity (Murphy & Eaton 1983). The restoration of canals for pleasure boating has been a controversial issue in recent years, and the management of the Basingstoke Canal. in particular, has been a subject of heated debate (see Byfield 1990). Proposals to use canals as part of a national water grid may also need to be evaluated by conservationists, and a knowledge of the dispersal behaviour and colonizing ability of both native and alien species will be essential if the consequences of linking canals are to be predicted. 4.2 REPRODUCTION AND DISPERSAL IN THE AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT In considering aquatic corridors, an important feature of aquatic plants must be borne in mind: the prevalence of vegetative reproduction in many genera. -

Shropshire Union Canal Conservation Area Appraisal

The Shropshire Union Canal Conservation Area Appraisal August 2015 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2 Summary of Special Interest, the Shropshire Union Canal Canal Conservation Area ..... 4 3 Historical Development…………………………...……………………………………………6 4 Location and Topography……………………………………………….…………………....11 5 Buildings and Structures of the Shropshire Union ........................................................ 14 6 Buildings, Setting and Views: Wheaton Aston Brook to Little Onn Bridge 28 7 Little Onn Bridge to Castle Cutting Bridge .................................................................... 31 8 Castle Cutting Bridge to Boat Inn Bridge ...................................................................... 35 9 Boat Inn Bridge to Machins Barn Bridge…………………………………………..………...39 10 Machins barn Bridge to Norbury Junction……………………………………………..……42 11 Norbury Junction and Newport Branch ......................................................................... 45 12 Norbury Junction to Grub Street Bridge ........................................................................ 55 13 Grub Street Bridge to Shebdon Wharf .......................................................................... 58 14 Shebdon Bridge to Knighton Wood .............................................................................. 66 15 Key Positive Characteristics ........................................................................................ 66 -

Stratford Upon Avon Canal Easy to Moderate Trail: Please Be Aware That the Grading of This Trail Was Set According to Normal Water Levels and Conditions

Stratford Upon Avon Canal Easy to Moderate Trail: Please be aware that the grading of this trail was set according to normal water levels and conditions. Weather and water level/conditions can change the nature of trail within a short space of time so please ensure you check both of these before heading out. Distance: 4 miles Approximate Time: 2-3 Hours The time has been estimated based on you travelling 3 – 5mph (a leisurely pace using a recreational type of boat). Type of Trail: One Way Waterways Travelled: Stratford Upon Avon Canal Type of Water: Canal Portages and Locks: One Nearest Town: Stratford Upon Avon Start: Warwick Old Road,Preston Bagot, Stratford upon Avon, Warwickshire, B95 5EF Finish Salter’s Lane, Bearley, Stratford upon Avon, Warwickshire, B95 6DT O.S. Sheets: Explorer Map (1:25 000) Stratford-upon- Avon & Evesham. OS Landranger Map (1:50 000) 151 Stratford-upon-Avon. Route Summary Licence Information: A licence is required to paddle on this waterway. See full details in useful information Paddle over the longest navigable canal aqueduct in below. England, under split bridges and the beautiful but hidden Stratford Canal in Warwickshire. Local Facilities: Shops and pubs are available in Henley and Wootton Wawen. There are no toilets or changing The route is rural and sets off from the small hamlet of facilities at the start or end of the trail. There is a train Preston Bagot, crossing the Stratford to Birmingham station in Henley, Wootton Wawen, Bearley and Road (A3400) at Wootton Wawen and finishing at the Wilmcote. Edstone Aqueduct. -

Stratford- Upon-Avon

3 4 0 0 6 A4 Stony Hill Obelisk Covert Potato Hill 9 3 4 B A I R M To Welcome Hills Hotel IN G Country Park H Clopton E A House N M A L R D N O A O D A O T AVI D R P D W K O AY C H I S To I RW B A L B W A A Wilmcote N A R E 3 N Temple 40 Y 0 R A T Hill (1 mile) E E W E L S R Stratford-upon-A E E S V D O A A L B S H E S C L O T I L R G G FA OC A FL C R W OO B OWE M P R B R ROAD L CLO C E U U C von Canal S L R B RB E OS S A RE Clopton Bluecap E G S O H E N IG A M Covert Golf Course V E E A W Tower M H NUE D YC LO R S L A F W N R IE A A E L S L O A E S D O G W Bishopton A H D S O N R W S L L D LA O Y S C E 6 E O L D 4 N E VER W R D R N A E Y C EY DRIVE M T A S R O A I S S The Dingles WA O RN R RT FT E O A E I K L S N N CL ' D D D V R C R A A O O ET A E O T D Coachroad P O R P R W D VE O ST M E Covert O S L A H L L R T E E F EA C O L G I ST C E G I E F R L E LD IELD A U C E L C R D E L E N S H K CL G N S Y R O A OSE RS E E E A A L S W V L T V C O C DU L O W O K A D P O A PT N E L O S L ON T D A E ' C Y T R A DE E T R C O N O P R L R D O N E H SE P E O WA R W E T CA CLO R PE O LUE SE K W D I S T B C A J BISH S G US I N Y C TI ETRD S NS A B W E H O V GC M Y I A ENU L R SW A L N E AC A L E WC D 3 E KT O T A L S 4 U R HOR W I W O E S M D O H 0 N O N R S E V E O P E 0 V A OA E O D T D SC A H A R Y J S O R S 'S A J E N G O P Avenue I MAL B M E W T E von R S A S S L River A E P C U P D H L I E LO L Farm J D E AR S D C A A OA T RO D O G PH O R H S Industrial M C L A E YA R 'S E R N L C NDP IPER W R Y To R A M N R ID L R O Y R Estate A D A C A R O