Stourbridge Canal That I Completed with the Royal Geographical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Beginner's Guide to Boating on Inland Waterways

Ti r A Beginner’s Guide To Boating On Inland Waterways Take to the water with British Waterways and the National Rivers Authority With well over 4,000 km (2,500 miles) of rivers and canals to explore, from the south west of England up to Scotland, our inland waterways offer plenty of variety for both the casual boater and the dedicated enthusiast. If you have ever experienced the pleasures of 'messing about on boats', you will know what a wealth of scenery and heritage inland waterways open up to us, and the unique perspective they provide. Boating is fun and easy. This pack is designed to help you get afloat if you are thinking about buying a boat. Amongst other useful information, it includes details of: Navigation Authorities British Waterways (BW) and the National Rivers Authority (NRA), which is to become part of the new Environment Agency for England and Wales on 1 April 1996, manage most of our navigable rivers and canals. We are responsible for maintaining the waterways and locks, providing services for boaters and we licence and manage boats. There are more than 20 smaller navigation authorities across the country. We have included information on some of these smaller organisations. Licences and Moorings We tell you everything you need to know from, how to apply for a licence to how to find a permanent mooring or simply a place for «* ^ V.’j provide some useful hints on buying a boat, includi r, ...V; 'r 1 builders, loans, insurance and the Boat Safety Sch:: EKVIRONMENT AGENCY Useful addresses A detailed list of useful organisations and contacts :: : n a t io n a l libra ry'& ■ suggested some books we think will help you get t information service Happy boating! s o u t h e r n r e g i o n Guildbourne House, Chatsworth Road, W orthing, West Sussex BN 11 1LD ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 1 Owning a Boat Buying a Boat With such a vast.range of boats available to suit every price range, . -

Copy of 2019 OSV Works V2

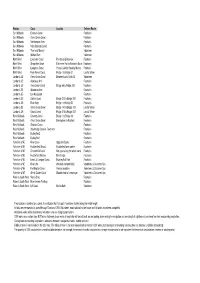

Region Canal Location Delivery Route East Midlands Erewash Canal Fountains East Midlands Grand Union Canal Fountains East Midlands Northampton Arm Fountains East Midlands Notts Beestob Canal Fountains East Midlands Trent and Mersey Volunteers East Midlands Welford Arm Volunteers North West Lancaster Canal Preston to Bilsborrow Fountains North West Shropshire Union Ellesmere Port to Nantwich Basin Fountains North West Llangollen Canal Poveys Lock to Swanley Marina Fountains North West Peak Forest Canal Bridge 1 to Bridge 37 Land & Water London & SE Grand Union Canal Between Locks 63 to 73 Volunteers London & SE Aylesbury Arm Fountains London & SE Grandunion Canal Bridge 68 to Bridge 209 Fountains London & SE Wendover Arm Fountains London & SE Lee Navigation Fountains London & SE Oxford Canal Bridge 215 to Bridge 242 Fountains London & SE River Stort Bridge 1 to Bridge 52 Fountains London & SE Grand Union Canal Bridge 140 to Bridge 181 Land & Water London & SE Oxford Canal Bridge 215 to Bridge 242 Land & Water West Midlands Coventry Canal Bridge 1 to Bridge 48 Fountains West Midlands Grand Union Canal Birmingham to Radford Fountains West Midlands Stratford Canal Fountains West Midlands Stourbridge Canal & Town Arm Fountains West Midlands Dudley No.2 Fountains West Midlands Dudley No.1 Fountains Yorkshire & NE River Ouse Opposite Docks Fountains Yorkshire & NE Huddersfield Broad Hudderfield town centre Fountains Yorkshire & NE Chesterfield Canal Hot spots along the whole canal Fountains Yorkshire & NE Hudderfield Narrow Milnsbridge Fountains -

Boating on Sussex Rivers

K1&A - Soo U n <zj r \ I A t 1" BOATING ON SUSSEX RIVERS NRA National Rivers Authority Southern Region Guardians of the Water Environment BOATING ON SUSSEX RIVERS Intro duction NRA The Sussex Rivers have a unique appeal, with their wide valleys giving spectacular views of Chalk Downs within sight and smell of the sea. There is no better way to enjoy their natural beauty and charm than by boat. A short voyage inland can reveal some of the most attractive and unspoilt scenery in the Country. The long tidal sections, created over the centuries by flashy Wealden Rivers carving through the soft coastal chalk, give public rights of navigation well into the heartland of Sussex. From Rye in the Eastern part of the County, small boats can navigate up the River Rother to Bodiam with its magnificent castle just 16 miles from the sea. On the River Arun, in an even shorter distance from Littlehampton Harbour, lies the historic city of Arundel in the heart of the Duke of Norfolk’s estate. But for those with more energetic tastes, Sussex rivers also have plenty to offer. Increased activity by canoeists, especially by Scouting and other youth organisations has led to the setting up of regular canoe races on the County’s rivers in recent years. CARING FOR OUR WATERWAYS The National Rivers Authority welcomes all river users and seeks their support in preserving the tranquillity and charm of the Sussex rivers. This booklet aims to help everyone to enjoy their leisure activities in safety and to foster good relations and a spirit of understanding between river users. -

Iwa Submission on the Environment Bill – Appendix A

IWA SUBMISSION ON THE ENVIRONMENT BILL – APPENDIX A IWA VISION FOR SUSTAINABLE PROPULSION ON THE INLAND WATERWAYS EXECUTIVE OVERVIEW 1. Recognising the UK Government’s strategy to reduce emissions from diesel and petrol engines, IWA formed its Sustainable Propulsion Group in 2019 to identify and monitor developments which will enable boats on the inland waterways to fully contribute to the Government’s stated aim of zero CO2 emissions by 2050. 2. The Group has identified a number potential solutions that it recommends should be progressed in order to ensure that boats used on the inland waterways do not get left behind in technological developments. These are outlined in more detail in this paper. 3. To ensure that the inland waterways continue to be sustainable for future generations, and continue to deliver benefits to society and the economy, IWA has concluded that national, devolved and local government should progress the following initiatives: Investment in infrastructure through the installation of 300 shore power mains connection charging sites across the connected inland waterways network. This would improve air quality by reducing the emissions from stoves for heating and engines run for charging batteries, as well as enabling a move towards more boats with electric propulsion. Working with navigation authorities, investment in a national dredging programme across the inland waterways to make propulsion more efficient. This will also have additional environmental benefits on water quality and increasing capacity for flood waters. Research and investment into the production, use and distribution of biofuels. This will be necessary to reduce the environmental impact of existing diesel engines which, given their longevity, will still be around until well after 2050. -

Waterway Dimensions

Generated by waterscape.com Dimension Data The data published in this documentis British Waterways’ estimate of the dimensions of our waterways based upon local knowledge and expertise. Whilst British Waterways anticipates that this data is reasonably accurate, we cannot guarantee its precision. Therefore, this data should only be used as a helpful guide and you should always use your own judgement taking into account local circumstances at any particular time. Aire & Calder Navigation Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Bulholme Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 6.3m 2.74m - - 20.67ft 8.99ft - Castleford Lock is limiting due to the curvature of the lock chamber. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Castleford Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom 61m - - - 200.13ft - - - Heck Road Bridge is now lower than Stubbs Bridge (investigations underway), which was previously limiting. A height of 3.6m at Heck should be seen as maximum at the crown during normal water level. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Heck Road Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.71m - - - 12.17ft - 1 - Generated by waterscape.com Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Leeds Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.5m 2.68m - - 18.04ft 8.79ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Crown Point Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.62m - - - 11.88ft Crown Point Bridge at summer levels Wakefield Branch - Broadreach Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.55m 2.7m - - 18.21ft 8.86ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2005-06

CONTACT DETAILS WATERWAYS BRITISH Head Office Customer Service Centre Willow Grange, Church Road, Willow Grange, Church Road, Watford WD17 4QA Watford WD17 4QA T 01923 226422 T 01923 201120 ANNUAL REPORT & F 01923 201400 F 01923 201300 PUBLIC BENEFITS [email protected] FROM HISTORIC WATERWAYS BW Scotland Northern Waterways Southern Waterways British Waterways ACCOUNTS 2005/06 Canal House, Willow Grange ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2005/06 Applecross Street, North West Waterways Central Shires Waterways Church Road Glasgow G4 9SP Waterside House, Waterside Drive, Peel’s Wharf, Lichfield Street, Watford T 0141 332 6936 Wigan WN3 5AZ Fazeley, Tamworth B78 3QZ WD17 4QA F 0141 331 1688 T 01942 405700 T 01827 252000 enquiries.scotland@ F 01942 405710 F 01827 288071 britishwaterways.co.uk enquiries.northwest@ enquiries.centralshires@ T +44 1923 201120 britishwaterways.co.uk britishwaterways.co.uk F +44 1923 201300 BW London E [email protected] 1 Sheldon Square, Yorkshire Waterways South West Waterways www.britishwaterways.co.uk Paddington Central, Fearns Wharf, Neptune Street, Harbour House, West Quay, www.waterscape.com, your online guide London W2 6TT Leeds LS9 8PB The Docks, Gloucester GL1 2LG to Britain’s canals, rivers and lakes. T 020 7985 7200 T 0113 281 6800 T 01452 318000 F 020 7985 7201 F 0113 281 6886 F 01452 318076 ISBN 0 903218 28 3 enquiries.london@ enquiries.yorkshire@ enquiries.southwest@ Designed by 55 Design Ltd britishwaterways.co.uk britishwaterways.co.uk britishwaterways.co.uk Printed by Taylor -

Romney Marsh Investigation REPORT

AGRICULTURAL LA:--ID COMMISSION AGRICULTURE ACT 1947 Romney Marsh Investigation REPORT LONDON: HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1949 TWO SHILLINGS N B T AGRICULTURAL LAND .COMMISSI\)N AGRICULTURE ACT 194/ Romney Marsh Investigation REPORT . LONDON: HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFIC 1949 •CONTENTS Paragraphs Pages TI!RMS OF R.EPEllENCB ••• s SECTION I. INTRODUCTION 6 (i) Procedure -... 2-3 6 (ii) Description of Area •.• 4-9 7 SECTION II. SoiLS, SEA-DEFENCE AND DRAINAGE ••• 9 (i) Soils .•• 10-18 9 (ii) Sea-Defence ... 19 10 (iii) Drainage 20-35 11 SECTION ill. RoMNEY MARSH AGRICULTURE-PAST AND PRESENT 14 _ (i) Period 1866-1939 3~2 16 (ii) War Period (1939-1945) 43-46 17 (iii) The Present (1948) ••• 47-49 17 SECTION IV. A REsTATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM 18 SECTION V. POSSIBLE FARMING SYSTEMS FOR FULL AND EFFICIENT PRODUCTION IN RoMNEY MARSH 19 (i) Sheep Farming 54 19 (ii) Dairy Farming 55-56 20 (iii) Arable Farming, including:Marl<:et Gardening ... 57-59 20 (iv) Ley Farming .. ., ..• • • 60:..62 21 SECTION VI. THE TILLAGE AREA UNDER A LEY SYSTEM ••• 22 (i) Extent of Tillage Acreage ... 63-65 22 (ii) Fatting Pastures and the Plough ... 66-67 23 (iii) Cropping Problems •.. 68-70 23 (iv) Use of Machinery ... 71 23 SECTION Vll. LIVESTOCK UNDER A LEY SYSTEM ••• 24 SECTION Vill. PRE-REQmSITE CONDmONS FOR A LEY FARMING SYSTEM IN RoMNEY MARSH 25 (i) Farp1ing Efficiency ... 78-80 25 (ii) Labour and Housing 81-87 26 (iii) Buildings and Roads 88-93 . 28 (iv) Land Drainage 94-98 31 (v) Public Services 99-104 32 SECTION IX. -

British Waterways Board General Canal Bye-Laws

BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD GENERAL CANAL BYE-LAWS 1965 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD BYE-LAWS ____________________ for regulation of the canals belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board (other than the canals specified in Bye-law 1) made pursuant to the powers of the British Transport Commission Act, 1954. (N.B. – The sub-headings and marginal notes do not form part of these Bye-laws). Application of Bye-laws Application of 1. These Bye-laws shall apply to every canal or inland navigation in Bye-Laws England and Wales belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board except the following canals: - (a) The Lee and Stort Navigation (b) the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal (c) the River Severn Navigation which are more particularly defined in the Schedule hereto. Provided that where the provisions of any of these Bye-laws are limited by such Bye-law to any particular canal or locality then such Bye-law shall apply only to such canal or locality to which it is so limited. These Bye-laws shall come into operation at the expiration of twenty-eight days after their confirmation by the Minister of Transport as from which date all existing Bye-laws applicable to the canals and inland navigations to which these Bye-laws apply (other than those made under the Explosives Act 1875, and the Petroleum (Consolidation) Act 1928) shall cease to have effect, without prejudice to the validity of anything done thereunder or to any liability incurred in respect of any act or omission before the date of coming into operation of these Bye-laws. -

Canals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour | Tours for Seniors in Britain

Australia 1300 888 225 New Zealand 0800 440 055 [email protected] From $13,995 AUD Single Room $15,995 AUD Twin Room $13,995 AUD Prices valid until 30th December 2021 23 days Duration England Destination Level 2 - Moderate Activity Canals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour | Tours for Seniors in Britain Oct 05 2021 to Oct 27 2021 An Industrial Revolution Tour for Seniors | Exploring Britain’s history through its canals and railways This small group tour uncovers British history through the canals and railways of the Industrial Revolution. Learn how the Industrial Revolution brought significant and lasting change to Britain. Discover how engineers overcame geographical obstacles using viaducts, bridges, aqueducts, tunnels, and locks. Witness first hand the groundbreaking technology and the many impressive structures that transformed Canals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour | Tours for Seniors in Britain 30-Sep-2021 1/15 https://www.odysseytraveller.com.au Australia 1300 888 225 New Zealand 0800 440 055 [email protected] Britain’s economy, some now restored for recreational purposes. However, our tour program is not only a study of the physical impact such a fundamental change made to world history. Led by local guides selected for their expertise, we also provide the opportunity to examine and discuss the resulting social upheaval. Packed to the brim with history, culture, and striking scenery, Great Britain and Ireland have a lot to offer the traveller. Our small group tour of the British isles are perfect for the mature or senior traveller who wants to explore the history of Britain and Ireland as part of an intimate guided tour with an expert local guide. -

Scotland's Great Glen Hotel Barge Cruise ~ Fort William to Inverness on Scottish Highlander

800.344.5257 | 910.795.1048 [email protected] PerryGolf.com Scotland's Great Glen Hotel Barge Cruise ~ Fort William to Inverness on Scottish Highlander 6 Nights | 3 Rounds | Parties of 8 or Less PerryGolf is delighted to offer clients an opportunity of cruising the length of Scotland’s magnificent Great Glen onboard the beautiful hotel barge Scottish Highlander, while playing some of Scotland’s finest golf courses. The 8 passenger Scottish Highlander has the atmosphere of a Scottish Country House with subtle use of tartan furnishings and landscape paintings. At 117 feet she is spacious and has every comfort needed for comfortable cruising. On board you will find four en-suite cabins each with a choice of twin or double beds. The experienced crew of four, led by your captain, ensures attention to your every need. Cuisine is traditional Scottish fare, salmon, game, venison and seafood, prepared by your own Master Chef. The open bar is of course well provisioned and in addition to excellent wines is naturally well stocked with a variety of fine Scottish malt whiskies. The itinerary will take you through the Great Glen on the Caledonian Canal which combines three fresh water lochs, Loch Lochy, Loch Oich, and famous Loch Ness, with sections of delightful man made canals to provide marine navigation for craft cutting right across Scotland amidst some spectacular scenery. Golf is included at legendary Royal Dornoch and the dramatic and highly regarded Castle Stuart, which was voted best new golf course worldwide in 2009. In addition you will play Traigh Golf Club (meaning 'beach' in Gaelic) set in one of the most beautiful parts of the West Highlands of Scotland with its stunning views to the Hebridean islands of Eigg and Rum, and the Cuillins of Skye. -

Marshlink Days out Guide 2021

Taster Tours About the Southeast Communities Marshlink Rail Partnership Days Out Guide 2021 Southeast Communities Rail Partnership (SCRP) connects communities to their vital community asset – their local station. We work across the southeast to help volunteers enrich the station environment through a wide variety of projects, for example through sustainable gardening and Historic Sea fronts art displays, festive decorations and so much more. With three miles of seafront from historic fishing huts to the bustle of arcades and funfairs Hastings has something for We improve integrated transport options by progressing access everyone. From the station head down to the seafront and to stations, working with our bus provider partners to increase follow The Stade Trail on foot or bike through the famous bus connectivity and encouraging active transport through fishing quarter, past the lifeboat station, East Hill funicular walking and cycling. We work with schools and local colleges, railway and the Fisherman’s museum. Afterwards perhaps providing educational workshops and we support diverse groups use the East Hill Funicular railway to reach Hastings Country to “Try a Train” through arranged visits to stations. Our line guides Park a fabulous nature reserve with stunning scenery just support social and economic development by encouraging right for a picnic. Set in 600 acres of ancient woodland and visitors to enjoy our region through sustainable travel. heathland the park lies in the High Weald AONB Find out how to get involved on our website: Medieval Towns www.southeastcrp.org Arriving in Rye you will find a well-preserved medieval town with half timbered houses and steep cobbled lanes. -

Shropshire Union Canal Conservation Area Appraisal

The Shropshire Union Canal Conservation Area Appraisal August 2015 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2 Summary of Special Interest, the Shropshire Union Canal Canal Conservation Area ..... 4 3 Historical Development…………………………...……………………………………………6 4 Location and Topography……………………………………………….…………………....11 5 Buildings and Structures of the Shropshire Union ........................................................ 14 6 Buildings, Setting and Views: Wheaton Aston Brook to Little Onn Bridge 28 7 Little Onn Bridge to Castle Cutting Bridge .................................................................... 31 8 Castle Cutting Bridge to Boat Inn Bridge ...................................................................... 35 9 Boat Inn Bridge to Machins Barn Bridge…………………………………………..………...39 10 Machins barn Bridge to Norbury Junction……………………………………………..……42 11 Norbury Junction and Newport Branch ......................................................................... 45 12 Norbury Junction to Grub Street Bridge ........................................................................ 55 13 Grub Street Bridge to Shebdon Wharf .......................................................................... 58 14 Shebdon Bridge to Knighton Wood .............................................................................. 66 15 Key Positive Characteristics ........................................................................................ 66