Cahiers D'études Africaines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MYSTIC LEADER ©Christian Bobst Village of Keur Ndiaye Lo

SENEGAL MYSTIC LEADER ©Christian Bobst Village of Keur Ndiaye Lo. Disciples of the Baye Fall Dahira of Cheikh Seye Baye perform a religious ceremony, drumming, dancing and singing prayers. While in other countries fundamentalists may prohibit music, it is an integral part of the religious practice in Sufism. Sufism is a form of Islam practiced by the majority of the population of Senegal, where 95% of the country’s inhabitants are Muslim Based on the teachings of religious leader Amadou Bamba, who lived from the mid 19th century to the early 20th, Sufism preaches pacifism and the goal of attaining unity with God According to analysts of international politics, Sufism’s pacifist tradition is a factor that has helped Senegal avoid becoming a theatre of Islamist terror attacks Sufism also teaches tolerance. The role of women is valued, so much so that within a confraternity it is possible for a woman to become a spiritual leader, with the title of Muqaddam Sufism is not without its critics, who in the past have accused the Marabouts of taking advantage of their followers and of mafia-like practices, in addition to being responsible for the backwardness of the Senegalese economy In the courtyard of Cheikh Abdou Karim Mbacké’s palace, many expensive cars are parked. They are said to be gifts of his followers, among whom there are many rich Senegalese businessmen who live abroad. The Marabouts rank among the most influential men in Senegal: their followers see the wealth of thei religious leaders as a proof of their power and of their proximity to God. -

Les Resultats Aux Examens

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar OFFICE DU BACCALAUREAT B.P. 5005 - Dakar-Fann – Sénégal Tél. : (221) 338593660 - (221) 338249592 - (221) 338246581 - Fax (221) 338646739 Serveur vocal : 886281212 RESULTATS DU BACCALAUREAT SESSION 2017 Janvier 2018 Babou DIAHAM Directeur de l’Office du Baccalauréat 1 REMERCIEMENTS Le baccalauréat constitue un maillon important du système éducatif et un enjeu capital pour les candidats. Il doit faire l’objet d’une réflexion soutenue en vue d’améliorer constamment son organisation. Ainsi, dans le souci de mettre à la disposition du monde de l’Education des outils d’évaluation, l’Office du Baccalauréat a réalisé ce fascicule. Ce fascicule représente le dix-septième du genre. Certaines rubriques sont toujours enrichies avec des statistiques par type de série et par secteur et sous - secteur. De même pour mieux coller à la carte universitaire, les résultats sont présentés en cinq zones. Le fascicule n’est certes pas exhaustif mais les utilisateurs y puiseront sans nul doute des informations utiles à leur recherche. Le Classement des établissements est destiné à satisfaire une demande notamment celle de parents d'élèves. Nous tenons à témoigner notre sincère gratitude aux autorités ministérielles, rectorales, académiques et à l’ensemble des acteurs qui ont contribué à la réussite de cette session du Baccalauréat. Vos critiques et suggestions sont toujours les bienvenues et nous aident -

Redalyc.Islam Y Género En La Diáspora Murid: Mirada Poscolonial a Feminismos Y Migraciones

methaodos.revista de ciencias sociales E-ISSN: 2340-8413 [email protected] Universidad Rey Juan Carlos España Massó Guijarro, Ester Islam y género en la diáspora murid: mirada poscolonial a feminismos y migraciones methaodos.revista de ciencias sociales, vol. 2, núm. 1, mayo, 2014, pp. 88-104 Universidad Rey Juan Carlos Madrid, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=441542971008 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto methaodos.revista de ciencias sociales, 2014, 2 (1): 88-104 Ester Massó Guijarro ISSN: 2340-8413 | DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17502/m.rcs.v2i1.40 Islam y género en la diáspora murid: mirada poscolonial a feminismos y migraciones Islam and gender in the Murid diaspora: postcolonial regard to feminisms and migrations Ester Massó Guijarro Departamento de Antropología Social, Universidad de Granada, España. [email protected] Recibido: 18-3-2014 Aceptado: 10-5-2014 Resumen La intención básica de este artículo es, a través de una pluralización de la mirada sobre “lo musulmán”, reflexionar en torno a las transformaciones contemporáneas operadas de facto en nuestras sociedades, sucedidas especialmente por la pluralización de prácticas y cosmovisiones convivientes, a menudo a raíz de situaciones migratorias. Se pluralizará la mirada sobre el islam a través de dos vías fundamentales: el abordaje del llamado “islam negro”, especialmente el practicado por las cofradías sufíes (la senegalesa Muridiyya, en concreto como ejemplo paradigmático), y una mirada desde el feminismo con sensibilidad poscolonial sobre aspectos cruciales de género presentes en tales cofradías. -

Report on Language Mapping in the Regions of Fatick, Kaffrine and Kaolack Lecture Pour Tous

REPORT ON LANGUAGE MAPPING IN THE REGIONS OF FATICK, KAFFRINE AND KAOLACK LECTURE POUR TOUS Submitted: November 15, 2017 Revised: February 14, 2018 Contract Number: AID-OAA-I-14-00055/AID-685-TO-16-00003 Activity Start and End Date: October 26, 2016 to July 10, 2021 Total Award Amount: $71,097,573.00 Contract Officer’s Representative: Kadiatou Cisse Abbassi Submitted by: Chemonics International Sacre Coeur Pyrotechnie Lot No. 73, Cite Keur Gorgui Tel: 221 78585 66 51 Email: [email protected] Lecture Pour Tous - Report on Language Mapping – February 2018 1 REPORT ON LANGUAGE MAPPING IN THE REGIONS OF FATICK, KAFFRINE AND KAOLACK Contracted under AID-OAA-I-14-00055/AID-685-TO-16-00003 Lecture Pour Tous DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publicapublicationtion do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States AgenAgencycy for International Development or the United States Government. Lecture Pour Tous - Report on Language Mapping – February 2018 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 5 2. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 12 3. STUDY OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 14 3.1. Context of the study ............................................................................................................. 14 3.2. -

BOPI N° 01NC/2019 Du 28 Mars 2019 Du N° 149177 Au N° 150676

BOPI 01NC/2019 GENERALITES SOMMAIRE TITRE PAGES PREMIERE PARTIE : GENERALITES 2 Extrait de la norme ST3 de l’OMPI utilisée pour la représentation des pays et organisations internationales 3 Clarification du Règlement relatif à l’extension des droits suite à une nouvelle adhésion à l’Accord de Bangui 4 Adresses utiles 5 DEUXIEME PARTIE : NOMS COMMERCIAUX 6 Noms Commerciaux du N° 149177 au N° 150676 7 1 BOPI 01NC/2019 GENERALITES PREMIERE PARTIE GENERALITES 2 BOPI 01NC/2019 GENERALITES Extrait de la norme ST.3 de l’OMPI Code normalisé à deux lettres recommandé pour la représentation des pays ainsi que d’autres entités et des organisations internationales délivrant ou enregistrant des titres de propriété industrielle. Bénin* BJ Burkina Faso* BF Cameroun* CM Centrafricaine,République* CF Comores* KM Congo* CG Côte d’Ivoire* CI Gabon* GA Guinée* GN Guinée-Bissau* GW GuinéeEquatoriale* GQ Mali* ML Mauritanie* MR Niger* NE Sénégal* SN Tchad* TD Togo* TG *Etats membres de l’OAPI 3 BOPI 01NC/2019 GENERALITES CLARIFICATION DU REGLEMENT RELATIF A L’EXTENSION DES DROITS SUITE A UNE NOUVELLE ADHESION A L’ACCORD DE BANGUI RESOLUTION N°47/32 LE CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION DE L’ORGANISATION AFRICAINE DE LAPROPRIETE INTELLECTUELLE Vu L’accord portant révision de l’accord de Bangui du 02 Mars demande d’extension à cet effet auprès de l’Organisation suivant 1977 instituant une Organisation Africaine de la Propriété les modalités fixées aux articles 6 à 18 ci-dessous. Intellectuelle et ses annexes ; Le renouvellement de la protection des titres qui n’ont pas fait Vu Les dispositions des articles 18 et 19 dudit Accord relatives l’objet d’extension avant l’échéance dudit renouvellement entraine Aux attributions et pouvoirs du Conseil d’Administration ; une extension automatique des effets de la protection à l’ensemble du territoire OAPI». -

Repertoire Structures Privees.Pdf

REPERTOIRE STRUCTURES PRIVEES EN SANTE LOCALISATION Nom de la structure TYPE Adresse Fatick FATICK DEPOT DE DIAOULE Dépôt COMMUNE DE DIAOULE Kolda VELINGARA DEPOT PHARMACIE BISSABOR Dépôt BALLANA PAKOUR PRES DU NOUVEAU MARCHE Kolda VELINGARA DEPOT BISSABOR /WASSADOU Dépôt CENTRE EN FACE SONADIS Ziguinchor ZIGUINCHOR DEPOT ADJAMAAT Dépôt NIAGUIS PRES DE LA PHARMACIE Kédougou SALEMATA DEPOT SALEMATA Dépôt KOULOUBA SALEMATA Dakar DAKAR CENTRE PHARMACIE DE L'EMMANUEL Pharmacie GRAND DAKAR A COTE GARAGE CASAMANCE OU ECOLE XALIMA Ziguinchor ZIGUINCHOR PHARMACIE NEMA Pharmacie GRAND DAKAR PRES DU MARCHE NGUELAW Dakar DAKAR CENTRE PHARMACIE NOUROU DAREYNI Pharmacie RUE 1 CASTOR DERKHELE N 25 Kédougou KEDOUGOU PHARMACIE YA SALAM Pharmacie MOSQUE KEDOUGOU PRES DU MARCHE CENTRAL Dakar DAKAR SUD PHARMACIE DU BOULEVARD Pharmacie RUE 22 X 45 MEDINA QUARTIER DAGOUANE PIKINE TALLY BOUMACK N545_547 PRES DE Dakar PIKINE PHARMACIE PRINCIPALE Pharmacie LA POLICE Dakar GUEDIAWAYE PHARMACIE DABAKH MALICK Pharmacie DAROU RAKHMANE N 1981 GUEDIAWAYE SOR SAINT LOUIS MARCHE TENDJIGUENE AVENUE GENERALE DE Saint-Louis SAINT-LOUIS PHARMACIE MAME MADIA Pharmacie GAULLE BP 390 Dakar DAKAR CENTRE PHARMACIE NDOSS Pharmacie AVENUE CHEIKH ANTA DIOP RUE 41 DAKAR FANN RANDOULENE NORD AVENUE EL HADJI MALICK SY PRES PLACE DE Thies THIES PHARMACIE SERIGNE SALIOU MBACKE Pharmacie FRANCE Dakar DAKAR SUD PHARMACIE LAT DIOR Pharmacie ALLES PAPE GUEYE FALL Dakar DAKAR SUD PHARMACIE GAMBETTA Pharmacie 114 LAMINE GUEYE PLATEAU PRES DE LOFNAC Louga KEBEMER PHARMACIE DE LA PAIX Pharmacie -

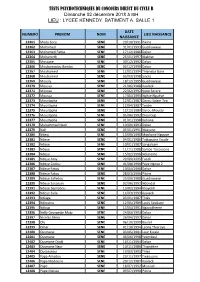

TESTS PSYCHOTECHNIQUES DU CONCOURS DIRECT DU CYCLE B Dimanche 02 Décembre 2018 À 08H LIEU : LYCEE KENNEDY

TESTS PSYCHOTECHNIQUES DU CONCOURS DIRECT DU CYCLE B Dimanche 02 décembre 2018 à 08H LIEU : LYCEE KENNEDY. BATIMENT A. SALLE 1 DATE NUMERO PRENOM NOM LIEU NAISSANCE NAISSANCE 12361 Mody Soce SENE 29/10/1991 Pikine 12362 Mohamed SENE 31/01/1993 Guediawaye 12363 Mohamed Farba SENE 17/12/1986 Dakar 12364 Mohameth SENE 25/01/1997 Niakhar 12365 Mossane SENE 30/12/1992 Dakar 12366 Mouhamadou Bamba SENE 02/12/1990 Dakar 12367 Mouhamed SENE 12/01/1994 Thieneba Gare 12368 Mouhamed SENE 03/03/1998 Sindia 12369 Mously SENE 18/12/1995 Guediawaye 12370 Moussa SENE 21/06/1988 Kaolack 12371 Moussa SENE 22/02/1992 Kone Serere 12372 Moussa SENE 17/04/1995 Ngèye Nguèye 12373 Moustapha SENE 12/01/1987 Darou Salam Typ 12374 Moustapha SENE 12/04/1987 Touba 12375 Moustapha SENE 12/12/1989 Darou Mousty 12376 Moustapha SENE 05/06/1992 Diouroup 12377 Moustapha SENE 01/01/1998 Kahone 12378 Muhammad Nazir SENE 10/09/1993 Dakar 12379 Nafi SENE 05/01/1991 Ndayane 12380 Ndew SENE 13/09/1996 Monkane Ngouye 12381 Ndeye SENE 04/01/1986 Tattaguine Escale 12382 Ndeye SENE 10/01/1987 Sangalcam 12383 Ndeye SENE 11/11/1988 Sambe Tocossone 12384 Ndeye SENE 15/02/1996 Ndiareme 12385 Ndeye Amy SENE 29/09/1995 Fatick 12386 Ndeye Codou SENE 04/08/1990 Peye Ngoye 2 12387 Ndeye Fatou SENE 10/04/1990 Dakar 12388 Ndeye Fatou SENE 28/03/1996 Pikine 12389 Ndeye Safietou SENE 25/09/1988 Guediawaye 12390 Ndeye Sassoum SENE 02/06/1992 Ndondol 12391 Ndeye Seynabou SENE 13/02/1994 Khayokh 12392 Ndeye Sylla SENE 14/03/1993 Kaolack 12393 Ndiaga SENE 03/01/1987 Thiés 12394 Ndiouma SENE 12/05/1989 -

Religious Agency, Memory and Travel Transnational Islam of Senegalese Murids in Helsinki

Religious Agency, Memory and Travel Transnational Islam of Senegalese Murids in Helsinki Aino Liisa Marjatta Peltonen University of Helsinki Department of World Cultures Study of Religions Master’s Degree Programme in Intercultural Encounters Master’s Thesis April 2014 Supervisor: Tuula Sakaranaho CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 The comings, the goings and the settlement of Muridism .......................................... 1 1.2 Previous research on Islam in the Finnish religious landscape ............................... 5 1.3 Previous research on Muridism and migration .............................................................. 7 1.4 Research questions ................................................................................................................. 14 2 THE MURID BROTHERHOOD ............................................................................................ 16 2.1 The early days of Muridism ................................................................................................. 16 2.2 The structure of followership ............................................................................................. 20 2.3 From rural to urban and overseas .................................................................................... 22 3 RESEARCHING MURIDISM IN HELSINKI ........................................................................ 25 3.1 Unprecedented encounters create the -

Touba La Capitale Des Mourides

Cheikh Guèye Touba La capitale des mourides . ENDA - KARTHALA - IRD TOUBA Collection « Hommes et Sociétés» Conseil scientifique: Jean-François BAY ART (CERI-CNRS) Jean-Pierre CHRÉTIEN (CRA-CNRS) Jean COPANS (Université Paris-V) Georges COURADE (IRD) Alain DuBRESSON (Université Paris-X) Henry TOURNEUX (CNRS) Directeur: Jean COPANS KARTHALA sur Internet: http://www.karthala.com Paiement sécurisé Couverture: Fidèles devant la grande mosquée de Touba (Magal Touba 2002). Photo: Arnaud Luce. © IRD Éditions et KARTHALA, 2002 ISBN (IRD) : 2-7099-1477-8 ISBN (KARTHALA) : 2-84586-262-8 Cheikh Guèye Touba La capitale des mourides Préface de Jean-Luc Piermay ENDA KARTHALA IRD 4, rue Kléber 22-24, bd Arago 213, rue La Fayette Dakar 75013 Paris 75010 Paris Remerciements Cet ouvrage est essentiellement le fruit d'une passion et d'un enthousiasme que j'ai toujours porté à la recherche en général. Mais il a été rendu possible par des soutiens nombreux et divers tout au long du travail. Le premier est celui de Jean-Luc Piermay qui m'a proposé le sujet et a suivi avec une attention soutenue tout le cheminement intellectuel et scientifique de la recherche. Il a été un directeur exigeant, rigoureux, mais ouvert et patient qui n'a ménagé aucun effort pour améliorer mes conditions de travail. Cet ouvrage est une contribution modeste à l'œuvre de Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba. Mais je ne l'aurais même pas commencé sans la caution morale et la bénédiction de Serigne Saliou Mbacké, khalife général des mourides. Qu'il soit vivement remercié. Je remercie également mon marabout Serigne Cheikh Saye Mbacké et ses collaborateurs, Diassaka Sarr, Pape Diallo, Issa Fall et Marone pour leur sollicitude et leurs encouragements. -

Sous Officiers Directs Acceptes

LISTE DES CANDIDATS SELECTIONNES AU CONCOURS DIRECT DES SOUS- OFFICIERS APRES ETUDE DES DOSSIERS N° Date Inscripti Prenom Nom Lieu Naissance Naissance on 44824 BORIS ROLAND ADIOYE 06/05/1990 OUSSOUYE 35071 JULIUS COLES ADIOYE 23/03/1993 DAKAR 33278 PALLA ADJ 16/03/2000 THILMAKHA 33040 CHEIKH AHMADOU BAMBA AIDARA 15/02/1988 MBOUR 37581 CHEIKHOU AIDARA 20/01/1998 MISSIRAH DINE 40128 HAMET AIDARA 06/05/1992 BAKEL 45896 MAFOU AIDARA 10/03/1993 THIONCK-ESSYL SINTHIANG SAMBA 35340 SEKOUNA AIDARA 18/05/1991 COULIBALY 41583 ASTOU AÏDARA 03/06/1996 DIONGO 43324 BABA AÏDARA 03/07/1990 DAROU FALL 44307 MOUSSA AÏDARA 15/08/1999 TAGANITH 41887 YVES ALVARES 25/12/1989 ZIGUINCHOR 36440 ABDOU LAHAT AMAR 17/04/1995 MBACKE 44118 SEYNABOU AMAR 02/01/1997 RUFISQUE 32866 BA AMINATA 27/12/1999 VELINGARA 42350 KHALIFA ABABACAR ANNE 14/07/1995 PIKINE 36701 OUMAR AMADOU ANNE 22/05/1992 PÈTE 47297 AGUSTINO ANTONIO 13/04/1992 DIATTACOUNDA 2 47370 ALIDA ALINESSITEBOMAGNE ASSINE 12/04/1999 CABROUSSE 39896 CHRISTIAN GUILLABERT ASSINE 18/06/1992 OUKOUT 41513 DANIEL ALEXANDRE MALICK AVRIL 27/05/1994 PARCELLES ASSAINIES 33240 ABIB NIANG AW 25/04/1991 DAKAR 38541 ARONA AW 31/03/1999 KAOLACK 36165 MAMADOU AW 09/10/1994 KEUR MASSAR 38342 NDEYE COUMBA AW 07/04/1990 DIOURBEL 42916 OUSMANE AW 14/09/1989 PIKINE 34756 ABDOU BA 20/10/1994 MBOUR 36643 ABDOUKARIM BA 02/04/1990 SAINTLOUIS 42559 ABDOUL BA 31/01/1998 LINGUERE 30471 ABDOUL BA 05/01/1999 PODOR 38377 ABDOUL AZIZ BA 25/09/1991 PIKINE 33148 ABDOUL AZIZ BA 10/10/1991 SAINT LOUIS 46835 ABDOUL WAHAB BA 12/03/1991 GUEDIAWAYE -

Republique Du Senegal Ministere De L'industrie Et

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL MINISTERE DE L’INDUSTRIE ET DES MINES ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ DIRECTION DE L’INDUSTRIE --------------------------------------------- PROGRAMME NATIONAL « PLATES-FORMES MULTIFONCTIONNELLES » POUR LA LUTTE CONTRE LA PAUVRETE (PN-PTFM) -------------------------------------------------- BILAN ANNUEL DES ACTIVITES 2013 DECEMBRE 2013 Bilan des activités 2013 SOMMAIRE I. RAPPEL INTRODUCTIF ...................................................................................................................................6 1.1 PRESENTATION DU PROGRAMME .......................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Zones d’intervention ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.2 Stratégie d’intervention ............................................................................................................... 6 1.1.2.1 Le Partenariat ............................................................................................................................. 7 1.1.2.2 L’approche du « faire-faire » .................................................................................................... 7 1.1.3 Organisation et fonctionnement ................................................................................................ 8 1.2 RAPPEL DU CONTEXTE........................................................................................................................... -

N° Nom Prénom Date Et Lieu De Naissance E-Mail Téléphone

République du Sénégal Ministère de l'Economie des Finances et du Plan DIRECTION GENERALE DES DOUANES Division de la Formation Liste des candidatures validées par centre Centre: Dakar N° Nom Prénom Date et lieu de naissance E-mail Téléphone Numero Inscription 1 FAYE DIENE 16/04/1988 / fatick [email protected] 77 290 99 08 ACD006084 2 GUEYE LIMAMOU 19/09/1988 / tattaguine [email protected] 77 028 48 50 ACD034724 3 KAMA ANNE SIMONE 07/07/1994 / thiadiaye [email protected] 77 172 55 39 ACD029515 m 4 KANDE SEYDOU 02/02/1990 / same kante [email protected] 77 685 04 12 ABD001747 m 5 KONATE PENE 12/05/1997 / diourbel [email protected] 77 757 57 12 COD027486 6 MBAYE CHEIIKH ALIOU 04/03/1991 / guediawaye [email protected] 77 963 22 87 ACD031818 7 NDONG SOULEYMANE 02/05/1996 / mbassis souleymanendong36@yahoo 78 137 66 55 ACD021726 .com 8 SENE ANTOINE 18/08/1994 / sorokh [email protected] 76 573 26 71 PRD021473 9 17511996020 MOUSTAPHA 09/09/1995 / dakar [email protected] 70 564 49 17 COD004692 84 10 17551992004 SOULEYMANE 12/01/1992 / dakar [email protected] 77 109 51 01 COD004125 30 11 17651993020 MOMAR NDAO 12/02/1993 / pikine [email protected] 77 201 82 16 ACD014971 20 12 19622002008 EL HADJ MALICK SY 01/02/1994 / darou khoudoss [email protected] 70 771 34 50 ACD005497 42 13 20062001005 MARIAMA SONKO 20/04/1991 / ebinako [email protected] 78 328 40 83 ACD037261 43 m 14 22412009000 BOUSSO 28/06/1993 / ndindy [email protected] 76 549 68 42 ACD032047 88 15 25482004004 NDEYE AISSATOU 31/03/1992 / kaolack dioufndeyeaissatou2@gmail.