O'bannon V. National Collegiate Athletic Association</Em>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luncheon Chair Luncheon Co-Chairs 2017 Committee

LUNCHEON CHAIR Sean McManus CBS Sports LUNCHEON CO-CHAIRS Mark Lazarus David Levy Peter Nelson Eric Shanks John Skipper NBC Sports Group Turner Broadcasting Systems, Inc. HBO Sports FOX Sports ESPN 2017 COMMITTEE MEMBERS Alyssa Atzeff Bryan Harris Tony Ponturo Steiner Sports Marketing, Inc. TAYLOR Ponturo Management Group, LLC Steiner Sports Memorabilia, Inc. Steven G. Horowitz Michael J. Principe Charles H. Baker Inner Circle Sports LLC TLA Worldwide plc DLA Piper W. Drew Hawkins Steve Raab Jared F. Bartie Morgan Stanley Global Sports & SportsNet New York Herrick, Feinstein LLP Entertainment Jay Rosenstein Robert C. Basche Howard Katz Headline Media Management Connect Sports & Entertainment National Football League Steve Rosner David Berson Michael Levine 16W Marketing, LLC CBS Sports CAA Sports Alec Shapiro Peter P. Bevacqua Jon Litner SONY Professional Solutions America PGA of America YES Network Lewis Sherr Joseph Cohen Hillary Mandel United States Tennis Association The Switch, Sports IMG Media Adam Silver Karen Cowen Steve Margosian National Basketball Association Cowen Media NBC Sports Group Dennis Spencer Bob Cramer Bernadette McDonald Lagardère Sports The Coca-Cola Company Major League Baseball Peter Stern Janis Delson Jon Miller The Strategic Agency Jade Media NBC Sports Group Suzanne Taddei Tracy Dolgin Jim O’Connell Tiffany & Co. YES Network, LLC NASCAR Steve Ulrich Jeff Filippi Scott O’Neil National Academy of Television MSG Networks, Inc. New Jersey Devils, Prudential Arts & Sciences Center, Philadelphia 76ers Don Garber LeslieAnne Wade Major League Soccer Neal Pilson Faldo Enterprises Pilson Communications, Inc. Michael Glantz Richard Weiss Headline Media Management Jon Podany SportsBusiness Journal LPGA Joshua Greenberg Catherine Yancy U.S. -

Gold Sponsors Print Media Sponsor PR/Social Media Sponsor Mission

Mission Sponsor Gold Sponsors Print Media Sponsor PR/Social Media Sponsor Abraham D. Madkour John Ruzich SportsBusiness Journal LEGENDS Scott Shapiro Hillary Mandel Sinclair Broadcast Group LUNCHEON CHAIR LUNCHEON CO-CHAIRS IMG Media Sean McManus, CBS Sports Pete Bevacqua, NBC Sports Group Rob Shaw Lenny Daniels, Turner Sports Steve Margosian Facebook Jimmy Pitaro, ESPN NBC Sports Group Eric Shanks, FOX Sports Lewis Sherr Bernadette McDonald United States Tennis Association COMMITTEE MEMBERS Major League Baseball Charles Baker Gary Gertzog Adam Silver O’Melveny & Myers LLP Fanatics Jon Miller National Basketball Association NBC Sports Group Jared Bartie Michael Glantz ICM Partners Scott Soshnick O’Melveny & Myers LLP Sandy Montag Sportico The Montag Group Robert C. Basche Joshua Greenberg Dennis Spencer Sygnificant Productions Bank of America Scott O’Neil Sportfive Private Bank Harris Blitzer David Berson Sports & Entertainment Bill Squadron CBS Sports Bryan Harris TAYLOR Neal Pilson Genius Sports Pilson Joseph Cohen Steven G. Horowitz The Switch, Sports Communications, Inc. Peter Stern Inner Circle Sports LLC The Strategic Agency Tony Ponturo Karen Cowen Kelly Hyne Ponturo Management Group, LLC Steve Ulrich Cowen Media LPGA National Academy Jason R. Coyle Michael J. Principe of Television Arts & Sciences Howard Katz GSE Worldwide Stadium National Football League LeslieAnne Wade Steve Raab Janis Delson Nick Kelly Wade Media Management SportsNet New York Jade Media Anheuser-Busch Seth Waugh Michael Levine Jeff Filippi Jay Rosenstein PGA -

Mgnno Gomes Have ______From Start to Finish

V. ' !• r- A-2 Timo3-Now3. Twtn Foilsoils. Idaho Mondoy.'Fobaiafyy 22 8 ,1 9 9 4 j --------------------r.----------------------- - ']■ Seastitrom ____ lecisioQ.tbmove. Continued from3m A1 Manlanufacturing is important. ny and made tbc decl Weath<ier The compony spent threee ;years Seastrom Manufaciifacturing vms start- 10 be in line wilh the Tl ------ r* "Wc want to iensive qJ in his grandfalh<atb er '8 garage as a other employer!ers around here,” he ,look3oking for a new. Icss-expe homome. And Scastrom and his1 ffamily small tool makingg sishop. The compa- said. ny then grew u pI .withw i (be cm ^ing .Manufacturing makes lik«Jced the Twin Falfs area. S caslrom Mai jmpany Soudiem Californialia iaerospace indus- ir Jb. 28. , electronic components ' ‘•We’re nol the kind o f corr The Accu-Weaeather® forecast for inoon, Monday, Feb. small washers, el hine parts. The compa- who/here the ovnicrs can live whencrc they try as a supplier. • and other machir n jtself. T he company haihas diversified so 4 0s )r th e day. IS 550 pages with morc wani/ant and let die pompany run 30s Lines separate> hihigh tem perature z o n e s for tf- n / s catalog has ofits products are items lisled’, although Solo 1Twin Fnlls was a good matiatch for lhat 95 pcrccnt of i thon 55,000 itet us American manu- ^ 1 0 s— Ihcre arc really only a thelie ccompany as well as a goodd imatch shipped to various J S. ; Seastromjaid thi in ie ^ including tb e ,. ■ liicts that'com e iii V ary -''foor rt] us," Scastrom said.----------■1* ------ ---- factitring companic; ^ few basic produc remaining 5 pcrcenl Isizes., • StStill, Scastrom and his familyly spent car makers. -

Plan Seeks Housing on Great Lawn M

24 — MANCHESTER HERALD. Wednesday. Mar. 22, 1989 STORE AND HELP WANTED HELP WANTED I MORTGAGES OFFICE SPACE ■■■■EaHHHnaWEHGaivNnwMR o f f i c e Manager for OFFICE space In Man r e c r e a t i o n v e h i c l e small company. Self % Spccioti^D^fif! I SAVE YOUR chester. 3 rooms. To- Joe’s World starter and organiza New looks Career man SERVICE PERSON • 9* HOMEII follng 900 square feet --------------y ........................................................................ tional skills a must. If you are In FORECLOSURE, on Spruce Street. Park Full or part time. Will Some bookkeeping and ing, one year lease Let’s Impose ban train. Apply Blonstein other diversified re- I VIDEO ICARPENTRY/ LEAKY ROOF? I MISCELLANEOUS BANKRUPTCY or DIVORCED $700. month. 643-6712 - Spring fashion '89: •46 years in military service, Camping Center. Route sponslbllltles. 646-1464. TAPINB REMODELING Mott rooft cm bt rtpairtd; SERVICES or "falling behind," ask for 647-0069._____________ 83, Vernon. CARPENTER’S Apprent In p ite t ol totti rtrooflng mpmstl NO PAYMENT PR08RAM up but no ‘super-duper patriot’ /5 on military guns /II Complftt rtrooflng o^ til typtt. MANCHESTER. One a supplement inside ice - Sunroom In- WEDDING Videos by FARRAND REMODELING to 2 years!! Buckland Square, 1075 RESTAURANT. Line stollers need assistant. FREe ESriMATES HAWKES TREE SERVICE A Royal Wedding Con- Room addltlona, decks, roof Tolland Turnpike, up Bucket, truck a chipper. Stump cook, pantry cook, and Learn a trade with real ceots. 649-3642. ing, aiding, windows and gutt- Manchester Roofing THE SWISS GROUP to 4225 sq, ft. -

Sports Journalism Has Not Been Exempt from These Tough Times

$5.00 October 2009 May 2010 News on the Level A SLIPPERY FIELD Signs point Sports Journalists Try an End Run to Stabilization Around Economic Challenges of Station Staffs Page 10 Page 5 TV Sports in Play Comcast Out for Clout With NBC Acquisition Page 24 NSSA Honors Sportscasters and Writers Pay Homage to Their Own Page 14 m`[\fgif[lZk`fej\im`Z\jn\YZXjk`e^ÔY\iZfee\Zk`m`kp jkl[`fj\im`Z\jm`[\fZfe]\i\eZ`e^n\Ym`[\f The National Press Club Broadcast Operations Center is a full-service multimedia production studio offering video production solutions, and studio and editing facilities in a comfortable, convenient downtown location. We pride ourselves in combining our unique facilities, experience, and creativity in capturing and communicating your message. 529 14th St. NW Suite 480 | Washington, D.C. 20045 | 202.662.7580 | [email protected] | pressclubvideo.org FROM THE EDITOR A Break in the Clouds Last month, after what seemed an eternity of doom-and-gloom Contents prognostications about the future of the TV news business, a ray of hope finally appeared in the form of the RTDNA-Hofstra University FEEDS l 4 In the wake of disappointing ratings Annual Survey. performances, CNN takes steps to market its Findings of the study, detailed in the story on Page 5 of this issue, journalistic strengths. show that stations actually have been broadcasting a record amount of * The latest RTDNA-Hofstra University study brings some promising news for TV journalists. news, despite having smaller staffs than ever. And even more comforting * ESPN sportscaster Erin Andrews looks ahead is the survey's determination that the era of relentless cutbacks has come after a troubling year. -

THE NCAA NEWS/June 7,1999

The NCAA Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association June 7,1969, Volume 26 Number 23 Committee CFA will continue studv of I-A play-off on costs 4 The College Football Association Ncinas conceded thcrc was “al- has appointed a committee to con ways a possibility” that changes in maps plan tinue studying a proposed 16-team the bowl system could negate the In its first meeting, the Special play-off and to evaluate the post- play-off proposal. Committee on Cost Reduction deve- season bowl structure. That translates into money. The loped an action plan that will include In addition, the CFA voted to 24 CFA teams that played in bowl six months of research and explora- submit legislation at next January’s games last season received $33.5 tion with a goal of legislation for NCAA Convention that would re- million. Revenue from the proposed consideration at the 1991 NCAA store the 30 initial grants per year play-off has been estimated at any- Convention. limit on football grants-in-aid (the where from %42million to $87 mil- The special committee, which current limit is 25). But the CFA lion, with all CFA members sharing was established by the adoption of members rejected a “recovery” plan the money. Proposal No. 39- 1 at the 1989 that would have allowed Division (See rehted story on page 4.) Convention, met May 30 to June 1 I-A schools under the limit to get Donnie Duncan, athletics director in Dallas. back to 95 total scholarships over a at the University of Oklahoma, said The resolution contained in Pro- two-year period. -

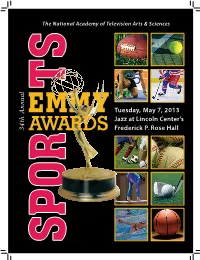

Sports 34Th Program Res Low.Pdf

The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences EMMY Tuesday, May 7, 2013 Jazz at Lincoln Center’s AWAR DS Frederick P. Rose Hall CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR SPORTS EMMY® 17 AWARDS NOMINEES OUTSTANDING EDITED SPORTS SERIES/ANTHOLOGY Hard Knocks: Training Camp With The Miami Dolphins Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel OUTSTANDING SPORTS JOURNALISM Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel—Hockey’s Darkest Day (Bernard Goldberg) Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel—Your Brain On Football (Bernard Goldberg) OUTSTANDING LONG FEATURE Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel—Chancellor Lee Adams: The Fighter (Bryant Gumbel) Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel—Steve Gleason: Tragic Hero (Jon Frankel) Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel—Two Of A Kind (Bernard Goldberg) OUTSTANDING CAMERA WORK 24/7 Pacquiao/Marquez 4 OUTSTANDING EDITING Hard Knocks: Training Camp With The Miami Dolphins 24/7 Pacquiao/Marquez 4 THE DICK SCHAAP WRITING AWARD 24/7 Pacquiao/Marquez 4 OUTSTANDING MUSIC COMPOSITION/DIRECTION/LYRICS Hard Knocks: Training Camp With The Miami Dolphins Namath OUTSTANDING POST PRODUCED AUDIO/SOUND 24/7 Pacquiao/Marquez 4 Hard Knocks: Training Camp With The Miami Dolphins OUTSTANDING SPORTS DOCUMENTARY Namath Klitschko (Broadview Pictures) CONTINUING THE STANDARD OF EXCELLENCE THE STANDARD CONTINUING ©2013 Home Box Offi ce, Inc. All rights reserved. HBO® and related channels and service marks are the property of Home Box Offi ce, Inc. ® 34th Annual SPORTS EMMY AWARDS n behalf of the 13,000 members of The National O Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, I am delighted to welcome each of you to the glamorous Frederick P. Rose Hall, home of Jazz at Lincoln Center for the 34th Annual Sports Emmy® Awards. -

A Long and Winding Road ❖

A Long and Winding Road IOC/USOC Relations, Money, and the Amateur Sports Act Stephen R. Wenn* In November 1978, U.S. President Jimmy Carter signed Public Law 95-606, known as the Amateur Sports Act (ASA), into law. It represented the U.S. government’s legislative response to the findings of the President’s Commission of Olympic Sports struck by Car- ter’s predecessor, President Gerald Ford, in 1975. Declining U.S. international sport results in the Cold War era, the surging levels of success enjoyed by Soviet athletes, and others from behind the “Iron Curtain,” as well as a dismal outcome for the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) at the 1972 Munich Olympics where administrative bun- gles and disappointing athlete performances grabbed the headlines, pushed Ford, and eventually federal legislators, to intervene. The central purpose of the ASA was to streamline the administration of U.S. Olympic affairs, and place the USOC in a better position to administer U.S. interests as a means of effecting change to the Olympic results table (by country). Less well known, or reported, at the time, were clauses that strengthened and broadened the USOC’s exclusive rights to the use of the Olympic five- ring logo in U.S. territory. USOC officials had lobbied Congress in advance of the pas- sage of the ASA for enhanced legal protection for the USOC’s rights to the use of Olym- pic marks and emblems. It would be a number of years before USOC officials truly understood the revenue generating platform that it had also received through these changes to the ASA. -

Pine Hill Man Denies Secret Burial

M - MANCHESTER HERALD. Wedttegday. May 25. IMS Tennis Noriega Nowhere to go Critics DelighteD with play appeal /3 with faileD talks/S VOLKSWAGEN. INC. Hanrhratpr HrralJi SPRING SPECIALS Thursday, May 26, 1988 Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm 30 Cents M ON ALL VOUB CHOICE Pine Hill man Denies secret burial MR'*'® 1988 VW By Andrew Yurkovsky unnamed witness to the aiieged connection with the case, which A A witnessed the alleged burial 4 with his lawyer, Hartford attor reached for comment this CABRIOLETS... Manchester Herald crime. has been classified "inactive” by shortly after she said It occurred. ney Hubert J. Santos, before he morning. Information from the witness, a th e Manchester Police He criticized the decision to leave decides whether he will take any Manchester police Capt. Jo 6 to choose from A Manchester man today de woman who was between 8 and 10 Department. his name in the affidavit while kind of legal action against seph H. Brooks, who heads the Claret Red nied the allegation in a search years old at the time, prompted Told that he was identified in deleting the names of the woman anyone in connection with the department's detective division, warrant affidavit that he attemp M anchester police last No the affidavit as the man who and witnesses to other incidents case. He would not speculate on on Wednesday also expressed ted to bury the body of a young vember to spend three days in the attempted to bury the reported related to the investigation. what that action would be. -

Factors in the Formation and Development of Professional Sports Leagues

Visions in Leisure and Business Volume 14 Number 1 Article 4 1995 Factors in the Formation and Development of Professional Sports Leagues Jack O. Gaylord Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions Recommended Citation Gaylord, Jack O. Jr. (1995) "Factors in the Formation and Development of Professional Sports Leagues," Visions in Leisure and Business: Vol. 14 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions/vol14/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Visions in Leisure and Business by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. FACTORS INTHE FORMATION AND DEVELOPMENT OF PROFESSIONAL SPORTS LEAGUES BY MR. JACK 0. GAYLORD, JR., PRESIDENT JACK 0. GAYLORD EVENTS, INC. 13419QUAKER STREET COLLINS, NEW YORK 14034 52 DOWNS A VENUE WHARTON, NEW JERSEY 07885 ABSTRACT keting strategies, ownership instability, exhorbitant player salaries, and minimal The purpose of the study was to develop a corporate sponsorship. The World Football frameworkto isolate the important factors in League (WFL), the United States Football the formation and development of a pro League (USFL), and the American Lacrosse fessional sports league. The method of data League (ALL) have joined the graveyard collection for this qualitative study was a with other notables such as the World modified Delphi technique, which included Hockey League and the Major Indoor a panel of eighteen individuals who possess Soccer League, while other professional expertise in the area of sport. There are sports teams have enjoyed a period of three major sections of findings in this longevity since being established. -

Cablevision Photos Folder List

CableVision photos folder list File Folder Other subjects 3 DO Company Trip Hawkins, Rick Tompane 700 Club Tim Robertson, Susan Howard, Ben Kinchlow, logo 900 Numbers Wheel of Fortune, Jeopardy, Jay Leno A & E Brooke Bailey Johnson, Lyle Schwartz, Sy Lesser, Michael Cascio, Martha Greenhouse, Gladys Nederlander, Susan Silver, Peggy Charren, Nickolas Davatzes, Drew Sheckler, Susan Wittenberg, Gary Loeffler, Carole Kealy, Tom Bradley, Susan Herman, Decker Anstrom, Dusty Morris, Todd Noyes, Michael Katz, Whitney Goit, Ronald Schneier, Annette Simand, William McGorry, James Gray, Ray Joslin, Ellen Agress, Mark Mersky, Rita Ellix, Stephanie Sills, Susan Schulman, Shelley Blaine, Lucy Chudson, Lawrence Widrig, Betty Cornfeld, Sherri London, Arlene Kekalos, Paulette McLeod, Gerard Gruosso, Robert Igiel, Lori Sue Meyers, Enid Karpeh, Ken Street, Randall McKey, Colin Watson, Andrew Orgel, Phil Lind, Daniel Davids, Lisa Cowles, Abbe Raven, Carolyn Reynolds, Susan Leventhal, Brian Litman, Steve Bouchard, David Lee A & E - programming programming A.B.C. Jack Healy, Paul Coss, Elton Rule A.B.C. Video Enterprises, Inc. Bruce Maggin, Thomas Bloniarz, graphic A.C.E. Cable Awards John Goddard, Kay Koplovitz, Char Beales, Bob Johnson A.C.L. Staff Photos Fred Cady, Bob, Holt, Rob Williams A.C.T.S. Stephen Baum, Thomas Rogeberg, Jimmy Allen, Gene Linder, Ronald Dixon, G. William Nichols, programming A.C.T.V. programming, Dr. Michael Freeman Ph.D., Andre Chagnon, John Lack, Dr. Diana Gagnon A.I.D.S. A.P. (Associated Press) Roy Steinfort, Robert Reed, Greg Groce, Tim Brennan, Jerry Astertay, Donald Harwood, Anne Nobles, Henry Heibrunn A.R.T.S. (Alpha Repertory Television Service) programming including Melba Moore "The Creative Drive", Jack Palance The Mysterious Eastern Zone", Peter Strauss "America, Where It All Happens", David Birney, Richard Thomas A.T.&T. -

The 5Th Annual Entertainment & Sports Law Symposium

The 5th Annual Entertainment & Sports Law Symposium Friday, April 12, 2019 Presented by The Entertainment & Sports Law Society SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW The Entertainment & Sports Law Society would like to thank the following College of Law faculty for their assistance in planning this event: ESLS Faculty advisor, Professor Laura Lape Dean Dagenais Professor Todd Berger Kim Wolf Price Sarah Collins Chris Ramsdell Table of Contents Agenda……………………………………………………………………………...i Panelist Biographies………………………………………………………………ii Panel 1: Music Licensing; The Impact of the Music Modernization Act………..1 Compulsory Licensing Statute…………………………………………………………….1 Amendments to the 1976 Act: 115th Congress, 2017-2018……………………………...48 Music Licensing Transformed by the Passage of the Music Modernization Act………...61 Music Streaming Cos. To Fight Copyright Board Royalty Hike…………………...……67 After Big Music Bill, 3 Other Copyright Proposals to Watch……………………….…..70 Panel 2: NCAA Amateurism; How Current Rulings in the Court System will Affect the College Game……………………………………………………….…74 NCAA Bylaw Article 12…………………………………………………………………74 Jenkins v. NCAA……………………………………………………………………….…90 Debunking the NCAA’s Myth that Amateurism Conforms with Antitrust Law: A Legal and Statistical Analysis………………………………………………………..107 Student Athletes vs. NCAA: Preserving Amateurism in College Sports Amidst the Fight for Player Compensation…………………………………………….137 The Value of Amateurism………………………………………………………………159 Equity and Amateurism: How the NCAA Self-Employment Guidelines are Justified and Do Not Violate Antitrust Law………………………………………….…211 NCAA Can’t Cap Student Athletes’ Education Related Play…………………………..234 NCAA’s Antitrust Violation ‘Pretty Clear’ Judge Says………………………………..239 Agenda CLE Registration: 9:45am – 10:40am Opening Remarks: 10:40am – 11:00am Panel 1: 11:00am – 12:15pm Music Licensing; The Impact of the Music Modernization Act Imraan Farukhi; Licensed Attorney and Assistant Professor of Television, Radio & Film at the S.I.