Supporting the Integration of Disadvantaged Groups Into the Labour Market and Society Final Report Volume III- Analysis of In-Depth Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flight Lieutenant Cy Grant

PEOPLE PROFILE BATTLE OF THE RUHR Flight Lieutenant Cy Grant The Battle of the Ruhr was a five month long campaign of strategic bombing of a major industrial Cy Grant moved from and his fellow prisoners area of Germany called the Ruhr. The targets British Guiana to the were forced to march in included armament factories, synthetic oil plants, coke plants, steelworks and dams. UK to join the RAF, as deep snow, with little rations, sleeping in barns and then the year before the being transported in cattle Operation Chastise was part of this battle and the RAF had removed its trucks to Lukenwalde, just official name for attacks on Germans dams on 16-17 bar and allowed blacks south of Berlin. By the end May 1943. The RAF Squadron that carried out the of the war, they were freed attacks were known as the ‘Dambusters’ and they Cy Grant published his from the colonies to by the Russians who ripped used specially developed ‘bouncing bombs.’ memoirs under the title join its ranks. down the fences with their ‘A Member of the RAF of tanks. Indeterminate Race*’. He got Operation Chastise: Fact File By 1943 Grant had received the attack on the Moehne, the title from a caption below D.O.B 8 November 1919 a commission and was one After the war he studied law Eder and Sorpe Dams by a picture of him in a German P.O.B British Guiana and qualified as a barrister No. 617 Squadron RAF of the few black officers in on the night of 16/17 May Newspaper in July 1943 “Ein Years of Service the RAF. -

WRAP THESIS Johnson1 2001.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/3070 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. David Johnson Total Number of Pages = 420 The History, Theatrical Performance Work and Achievements of Talawa Theatre Company 1986-2001 Volume I of 11 By David Vivian Johnson A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in British and Comparative Cultural Studies University of Warwick, Centre for British and Comparative Cultural Studies May 2001 Table of Contents VOLUMEI 1. Chapter One Introduction 1-24 ..................................................... 2. Chapter Two Theatrical Roots 25-59 ................................................ 3. ChapterThree History Talawa, 60-93 of ............................................. 4. ChapterFour CaribbeanPlays 94-192 ............................................... VOLUME 11 5. ChapterFive AmericanPlaYs 193-268 ................................................ 6. ChapterSix English Plays 269-337 ................................................... 7. ChapterSeven Conclusion 338-350 ..................................................... Appendix I David Johnsontalks to.Yv6nne Brewster Louise -

Black British Plays Post World War II -1970S by Professor Colin

Black British Plays Post World War II -1970s By Professor Colin Chambers Britain’s postwar decline as an imperial power was accompanied by an invited but unprecedented influx of peoples from the colonized countries who found the ‘Mother Country’ less than welcoming and far from the image which had featured in their upbringing and expectation. For those who joined the small but growing black theatre community in Britain, the struggle to create space for, and to voice, their own aspirations and views of themselves and the world was symptomatic of a wider struggle for national independence and dignified personal survival. While radio provided a haven, exploiting the fact that the black body was hidden from view, and amateur or semi-professional club theatres, such as Unity or Bolton’s, offered a few openings, access to the professional stage was severely restricted, as it was to television and film. The African-American presence in successful West End productions such as Anna Lucasta provided inspiration, but also caused frustration when jobs went to Americans. Inexperience was a major issue - opportunities were scarce and roles often demeaning. Following the demise of Robert Adams’s wartime Negro Repertory Theatre, several attempts were made over the next three decades to rectify the situation in a desire to learn and practice the craft. The first postwar steps were taken during the 1948 run of Anna Lucasta when the existence of a group of black British understudies allowed them time to work together. Heeding a call from the multi-talented Trinidadian Edric Connor, they formed the Negro Theatre Company to mount their own productions and try-outs, such as the programme of variety and dramatic items called Something Different directed by Pauline Henriques. -

London Metropolitan Archives Ic and Jessica

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 HUNTLEY, ERIC AND JESSICA {GUYANESE BLACK POLITICAL CAMPAIGNERS, COMMUNITY WORKERS AND EDUCATIONALISTS} LMA/4463 Reference Description Dates BUSINESSES AMERICAN LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY Correspondence and agreements LMA/4463/A/01/01/001 Eric Huntley's signed agent agreement with 1968 - 1979 amendment. Monthly performance appraisal letters evaluating sales results Includes later amendment agreement. Sales results were monitored by his agency managers Raymond Eccles and Charles Patterson. Also an annotated draft speech composed by Eric Huntley on Raymond Eccles' relocation to the West Indies. Client's insurance claim details with carbon copy suicide letter attached (1968-1969) 1 file Printed material LMA/4463/A/01/02/001 'Who's Who' directory for the Las Palmas 1973 Educational Conference: containing images of staff by country 1 volume LMA/4463/A/01/02/002 Eric Huntley's personalised company calendar 1976 Unfit 1 volume LMA/4463/A/01/02/003 Grand Top Club Banquet menu with signatures. 1971 - 1972 Training material and sales technique leaflets. Itinerary for American Life Convention in Rhodes, Greece. Includes Eric Huntley's business card. 1 file Certificates and badge LMA/4463/A/01/03/001 Certificates of achievements for sales, training 1968 - 1976 and entrance into the Top Club conference 1 file LMA/4463/A/01/03/002 Badge with eagle, globe and stars emblem 196- - 197- Metal thread on fabric 1 badge Photographs LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 HUNTLEY, ERIC AND JESSICA {GUYANESE BLACK POLITICAL CAMPAIGNERS, COMMUNITY WORKERS AND EDUCATIONALISTS} LMA/4463 Reference Description Dates LMA/4463/A/01/04/001 Insurance Convention, Republic of Malta 1969 Black and white. -

T&T Diplomat Newsletter March 2010

the T&T SPECIAL 2009 YEAR IN REVIEW ISSUE April 2010 The Official Monthly Publication of the Embassy of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, Washington DC diplomat and Permanent Mission of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago to the Organization of American States in this issue THE FIFTH SUMMIT OF THE AMERICAS HIGHLIGHTS US President Barack Obama in Trinidad and Tobago STEELPAN TAKES WASHINGTON DC BY STORM BP Renegades performs to a sold-out audience at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts LAUNCH OF THE TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL CENTRE T&T Hits The International Financial Stage IMPORTANT NEW INFORMATION Embassy of T&T Launches the First Mobile Immigration Unit www.ttembassy.com & diplomatT T COVER Honourable Patrick Manning, Prime Minister of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago greets US President Barack Obama during the Fifth Summit of the Americas which was held in April 2009 in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 5 GREETINGS FROM THE AMBASSADOR 6 SUMMIT SUCCESS 11 TRADE AND INVESTMENT: a. NS & J Advisory Group Trade Mission to Trinidad and Tobago b. Launch of the Trinidad and Tobago International Financial Centre c. Honourable Mariano Browne Convinces Washington Business Elite to “Do Business in Trinidad and Tobago” d. Global Business Cooperative Trade Mission 16 FEATURE SPEECH: Statement by the Honourable Patrick Manning at the United Nations Climate Change Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark 19 Washington DC Celebrates The History of the Steelpan with an Oral Pictorial Presentation by Dr. Kim Johnson 20 THE DIASPORA CELEBRATES: - Spiritual Shouter Baptist Liberation Celebration - Indian Arrival Day Celebration - Independence Celebrations - Divali Celebrations 28 CARIBBEAN GLORY – A Tribute to World War II Caribbean Heroes 31 DIASPORA FOCUS: Dr. -

They Also Flew in Freedom's Cause a Brief History of British West

They Also Flew in Freedom's Cause A Brief History of British West Indians in the Royal Air Force in World War II - Defence Viewpoints from UK Defence Forum Friday, 05 February 2021 17:01 A contribution (DV14) to our series "Distant Voices" By Gabriel J. Christian. President East Coast Chapter Tuskegee Airmen (2018-2020) wwww.ecctai.org. This article is also published by Gabriel at academia.edu with further illustrations Around seven thousand British West Indians - including my father seen here -Â served in the British armed forces during World War II. When Britain declared war on September 19, 1939, the Royal Air Force (RAF) itself was compelled to overcome the prejudices of the time. After the defeat of France in 1940 and the retreat of the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk, Britain found itself in dire straits. With advocacy by progressive Britons and British West Indians who spoke out against segregation, the RAF, to its credit, integrated its ranks. Around 7,000 British West Indians rallied to freedom's cause and served as fighter pilots, bomb aimers, air gunners, ground staff and administration. No other colonies, or group of nations, contributed more airmen to the RAF during World War II. This is even more remarkable, and their commitment more profound, given the small populations of the islands. Several Africans from Ghana, Nigeria and Sierra Leone also became officers in the RAF, with the most notable being RAF Flight Lieutenant Johnny Smythe of Sierra Leone, who was shot down over Germany on his 28th mission and survived imprisonment in the famous Stalag Luft One. -

GENERAL ELECTION Results in Sound and Television

GENERAL ELECTION Results in Sound and Television Polling Day is Thursday, May 26, and on that night and the following day results will be broadcast in the Home Service, the Light Programme, and on Television as they are received. Full details of the BBC's plans for these broadcasts are given on page 3. 'Radio Times' Election Chart In this issue is a three-page chart for the benefit of listeners who wish to record the results. It lists the 630 constituencies in alphabetical order and in the form in which their names will be announced over the air. Broadcasting the General Election Results WHENthe polling booths close at nine o'clock on Thursday evening The electronic com- will be in readiness for the of the everything start complex puter which will be broadcasting operation which will give the nation the results of used to help in the the General Election with the least possible delay, together with periodic assessment of Elec- announcements of the state of the parties, analysis and interpretation of tion results. It is a the results by expert statisticians and commentators, and Election news digital computing from various parts of the country. engine working on The first result is to flicker over the tapes in the newsroom two storage capaci- expected or ' at BBC about 90 minutes after the close of the poll. At the ties memories.' headquarters One ' is a last Election four results were received before 11 midnight memory ' p.m.; by high-speed machine the total had two hours 178 results came risen to 105. -

2018 FACULTY SCHOLARSHIP REPORT DESIGN and LAYOUT Nick Paulus Keara Mangan Lucy Zhang

2018 FACULTY SCHOLARSHIP REPORT DESIGN AND LAYOUT Nick Paulus Keara Mangan Lucy Zhang PHOTOGRAPHY Elizabeth Torgerson-Lamark/RIT PUBLISHED BY The Wallace Center - RIT Open Access Publishing OFFICE OF THE PROVOST www.rit.edu/provost/ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Letter from the Provost 4 B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing & Information Sciences 24 College of Art and Design 36 College of Engineering Technology 50 College of Health Sciences & Technology 58 College of Liberal Arts 80 College of Science 104 Golisano Institute for Sustainability 112 International Campuses 116 Kate Gleason College of Engineering 134 National Technical Institute for the Deaf 158 Saunders College of Business 166 School of Individual Study Letter from the Provost I am delighted to present this 2018 Faculty Scholarship Report. This compendium of scholarly work by RIT faculty and students represents the best of who we are as scholars and creative artists. I hope you will take pride in your own and others’ awards, articles, books, juried exhibitions, editorships and other scholarly work highlighted here. The scholarly and artistic efforts within this report are examples of significant individual and group achievement. This work ranges from identifying antibacterial agents that promote burn wound healing, to building better barriers to cyberterrorism, to exploring representations of disability stigma in the media. It puts RIT and its research at the very heart of some of the world’s most critical technical, scientific, and social challenges. The impact of these accomplishments is also making a difference to RIT’s national reputation. For example, as the result of many recent research successes, we are now classified by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education as Carnegie Research 2. -

Windrush Foundation Celebrates 25 Years Of

WINDRUSH FOUNDATION CELEBRATES 25 YEARS OF HERITAGE AND COMMUNITY ADVOCACY IN SUMMER OF 2020 WINDRUSH FOUNDATION CELEBRATES 25 YEARS OF HERITAGE AND COMMUNITY ADVOCACY IN SUMMER OF 2020 UPDATED 1995 was the year which first saw Sam King and Arthur Torrington (co-founders) working to establish a CHARITY that delivered heritage and community services, helping to create an identity for Caribbean people, especially the youth, in Britain. ‘Windrush’, ‘Empire Windrush’ and ‘Windrush Generation’ have always been key words in our operations. Both men developed the idea, but Sam was the one to have led the first Windrush commemorative event (40th anniversary) in 1988, hosted by Lambeth Council. He had been a passenger on the Empire Windrush, an RAF WWII serviceman and the first Black Mayor of Southwark, London. He was first to have coined the term, ‘Windrush Generation’. There was no support from any Local Authority, except Lambeth, in 1998 when we held the 50th anniversary, and national newspaper, The Times, was the first to carry our publicity early in 1998. Arthur has also been the Director responsible for publicity from 1995 and who first contacted The Times newspaper in 1998. Sam brought together in 1988, 1998 and 2003 dozens of his fellow Windrush passengers. Below are some of WINDRUSH FOUNDATION’S major events, and associated activities over the past 25 years: 22.10.97: House of Commons Reception hosted by (the late) Bernie Grant MP 30.05.98: WINDRUSH - four-part series of one-hour documentaries on BBC2 TV 18.06.98: Windrush Reception at Foreign & Commonwealth Office hosted by Robin Cook MP, and attended by Tony Blair MP, Prime Minister 22.06.98: University of London, Logan Hall: Participants included: Bill Morris, Baroness Valerie Amos, Paul Boateng MP, Peter Bottomley MP, Professor Lola Young, Simon Hughes MP, Trevor Phillips, Oona King MP, and others. -

Download the Program

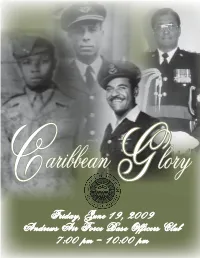

C aribbean G lory Friday, June 19, 2009 Andrews Air Force Base Officers Club 7:00 pm - 10:00 pm Few people know that thousands of British West Indians served in the British armed forces during World Wars I and II. Those who served in World War I, such as Norman Washington Manley (Jamaica), Captain Arthur Cipriani (Trinidad), and Tubal Uriah “Buzz” Butler (Grenada/Trinidad) went on to become leaders for beneficial social change which enhanced freedom and democracy in the British West Indies. When World War II broke out on September 19, 1939, many British West Indians answered the call. About 16,000 West Indians volunteered for service alongside the British during the Second World War. Wendell Christian and Twistleton Bertrand served in the South Caribbean Forces which was created to secure the southern part of the region closest to Trinidad’s oil industry and the vital refineries in Curacao then under attack by marauding German U-Boats. Over 100 British West Indian women were posted overseas of which 80 chose the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) for their contribution, while around 30 joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS). There were many more ATS and WAAF service women who stayed in the Caribbean region and did local duty. Around 7,000 West Indians served with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in roles from fighter pilots to bomb aimers, air gunners to ground staff and administration. No other colony contributed more airmen to the RAF than those from the British West Indies. -

At School Today

Key stage 3 History, English, Art fusion skills At School Today Have you ever had a day like Accabre? Write a few verses about a challenging day you’ve had at school. Think about how it made you feel, and how you responded to it. Are there any images that really stand out when you read the poem? Can you draw the strongest picture? Accabre Huntley wrote this poem when she was nine years old. Her book of poems called ‘At School Today’ was published in 1977. Additional Information for Teachers Accabre is the daughter of the pioneering Black publishers and activists Jessica and Eric Huntley, who migrated to Britain from Guyana in 1958. The London Metropolitan Archives holds the archive of their lives and work. View the London Metropolitan Archives’ Twentieth Century British Black History resource on TES, based on the Eric and Jessica Huntley Archive: Key stage 3 History, PSCHE fusion skills Mollie Hunte What supplementary services could your school or community provide to support families and pupils in schools today? Which ones would you like to see? Programme for 1981 day conference ‘Black Youth, Community, and Employment’. Additional Information for Teachers Mollie Hunte was born in Guyana in 1932. She came to England to continue her higher education and became an educational psychologist, supporting young people by assessing any difficulties they may have had with their learning. Mollie founded and co-founded many organisations for her community including the Caribbean Parents Group (1975) and the Caribbean Parents Group Supplementary Schools (1978). These groups were set up to support Black children and parents and their education, mental health and money management. -

A Rough Guider's Take on Early Flight

How the Ascension Scanner appeal: got its What do you name - remember Back page of life on the island? - Page 6 March 2010 Number 2 A rough guider’s take on early flight Page 3 With highlights from Ariel Nigel’s last stand over that Good Friday... Centre pages News The honorary islander Life for former BBC press officer Chris Bates (left) took an unexpected turn after he retired. He went to work for the Royal Norwegian Embassy in London, where he discovered that there are strong ties between Norway and the island of Tristan da Cunha. As a result he became friends with islanders and, ultimately, an unpaid representative of the government of Tristan. Such representatives are vital for a community for whom travel to other parts of the world can take months. Thus, after similar conferences on Reunion Island and in the Cayman Islands, he found himself on neighbouring Ascension Island to discuss the threat facing the Tristan Albatross and other species. ‘So I've had to learn rapidly about the issues with the help of organisations such as the RSPB, the Joint Nature Conservation Council and other bodies, and the conservation departments on Ascension, St. Helena, Falklands, South Georgia, Gibraltar, Turks and Caicos etc’ Chris, pictured with Ascension Heritage Society volunteer Roy Haley, adds: ‘My old Stanley Gibbons stamp catalogues come in PROSPERO very handy!’ March 2010 • See 1966 and all that – centre pages Prospero is provided free to Alert over errors in retired BBC employees. It can also be sent to spouses or dependants who want to keep pensioner tax codes in touch with the BBC.