Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REN Playbill.Indd 1 6/4/14 2:44 PM Contents

REN_playbill.indd 1 6/4/14 2:44 PM Contents ANCIENT EVENINGS.........................2 MAP..........................................................4 REN..........................................................7 THE SON ALSO Rises.....................8 Neville Wakefield LIBRETTO...........................................16 NOTES ON THE MUSIC....................21 Zach Baron PROFILES............................................24 CAST AND CREW..............................26 WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST.........28 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION......31 “...Ren, one’s Secret Name, who left at once, even as a falling star might drop through the sky. That is as it must be, I concluded. For the Ren did not belong to the man, but came out of the Celestial Waters to enter an infant in the hour of his birth and might not stir again until it was time to go back. While the Secret Name must have some effect on one’s character, it was certainly the most remote of our seven lights.” Norman Mailer Ancient Evenings The use of any recording device, either audio or video, and the taking of photographs, either with or without flash, is strictly prohibited. Please turn cellular phones off, as it interferes with audio recording equipment and telecommunications. Thank you. REN_playbill.indd 2-1 6/4/14 2:44 PM Ancient Evenings Ancient Evenings EN is the first act of “Ancient Evenings,” a collaborative project by Matthew expanses of salt beds beneath Michigan. KHU is the only act that will feature all RBarney and Jonathan Bepler that is inspired by American author Norman three automobiles. BA, the final live act, will take place in New York City as the Mailer’s 1983 novel Ancient Evenings, set in ancient Egypt. A nontraditional opera, automobile is further transformed into the 2001 Ford Crown Victoria. -

Spinks-TNMR-2015-Reflections-On

Edinburgh Research Explorer Increasing the real life in ourselves Citation for published version: Spinks, L 2015, 'Increasing the real life in ourselves: Reflections on Norman Mailer’s 'Politics of State'', The Mailer Review, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 157-76. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Mailer Review General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1 “Increasing the Real Life in Ourselves: Reflections on Norman Mailer’s Politics of State.” Dr Lee Spinks University of Edinburgh In the spring of 1969 Norman Mailer, fresh from his triumphant receipt of the Pulitzer Prize for The Armies of the Night, created a media sensation by announcing his entry into the Democratic Primary for the Mayoralty of New York City. The headline-grabbing centrepiece of his campaign was a call for the radical decentralisation of political power culminating in the establishment of the city of New York as the fifty-first state of the Union. -

The White Negro

THE WHITE NEGRO Superficial Reflections on the Hipster Norman Mailer Our search for the rebels of the generation led us to the hipster. The hipster is an enfant terrible turned inside out. In character with his time, he is trying to get back at the conformists by lying low ... You can't interview a hipster because his main goal is to keep out of a society which, he thinks, is trying to make everyone over in its own image. He takes marijuana because it supplies him with experiences that can't be shared with "squares." He may affect a broad-brim- med hat or a zoot suit, but usually he prefers to skulk un- marked. The hipster may be a jazz musician; he is rarely an artist, almost never a writer. He may earn his living as a petty criminal, a hobo, a carnival roustabout or a free-lance moving man in Greenwich Village, but some hipsters have found a safe refuge in the upper income brackets as television comics or movie actors. (The late James Dean, for one, was a hipster hero.) ... It is tempting to describe the hipster in psychiatric terms as infantile, but the style of his infan- tilism is a sign of the times. He does not try to enforce his will on others, Napoleon-fashion, but contents himself with a magical omnipotence never disproved because never tested. ... As the only extreme nonconformist of his generation, he exercises a powerful if underground appeal for conformists, through newspaper accounts of his delinquencies, his struc- tureless jazz, and his emotive grunt words. -

Project Apollo: Americans to the Moon John M

Chapter Two Project Apollo: Americans to the Moon John M. Logsdon Project Apollo, the remarkable U.S. space effort that sent 12 astronauts to the surface of Earth’s Moon between July 1969 and December 1972, has been extensively chronicled and analyzed.1 This essay will not attempt to add to this extensive body of literature. Its ambition is much more modest: to provide a coherent narrative within which to place the various documents included in this compendium. In this narrative, key decisions along the path to the Moon will be given particular attention. 1. Roger Launius, in his essay “Interpreting the Moon Landings: Project Apollo and the Historians,” History and Technology, Vol. 22, No. 3 (September 2006): 225–55, has provided a com prehensive and thoughtful overview of many of the books written about Apollo. The bibliography accompanying this essay includes almost every book-length study of Apollo and also lists a number of articles and essays interpreting the feat. Among the books Launius singles out for particular attention are: John M. Logsdon, The Decision to Go to the Moon: Project Apollo and the National Interest (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1970); Walter A. McDougall, . the Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age (New York: Basic Books, 1985); Vernon Van Dyke, Pride and Power: the Rationale of the Space Program (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1964); W. Henry Lambright, Powering Apollo: James E. Webb of NASA (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995); Roger E. Bilstein, Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles, NASA SP-4206 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1980); Edgar M. -

Charles Cw Cooke Victor Davis Hanson

20151207 upc_cover61404-postal.qxd 11/17/2015 6:46 PM Page 1 December 7, 2015 $4.99 VICTOR DAVIS HANSON: HELEN ANDREWS: The Islamic War The Campus Revival LIKE A THE RETURN OF PREROGATIVE ROYAL POWER CHARLES C. W. COOKE www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 11/16/2015 1:40 PM Page 2 base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 11/16/2015 1:45 PM Page 3 TOC_QXP-1127940144.qxp 11/18/2015 2:47 PM Page 1 Contents DECEMBER 7, 2015 | VOLUME LXVII, NO. 22 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 30 Shall We Have a King? Victor Davis Hanson on war and terrorism If, as the American system presumes, we all have a right to p. 18 a voice in making the laws that limit our freedom—and if there is a BOOKS, ARTS branch for which we vote that & MANNERS is charged with determining REDISCOVERING KIRK those laws—it is nothing short 42 Wilfred McClay reviews Russell of tyrannical for the state to deny Kirk: American Conservative, by Bradley J. Birzer. us that right, regardless of whether we approve of what is being 43 NOT ENOUGH TO SUCCEED Terry Teachout reviews done in our na me. Charles C. W. Cooke Empire of Self: A Life of Gore Vidal, by Jay Parini. COVER: THOMAS REIS 46 GETTING A GRIP ON ARTICLES THE GIPPER Steven F. Hayward reviews Finale: 18 THE ISLAMIC WAR by Victor Davis Hanson A Novel of the Reagan Years, Was Thucydides right about democracies in peril? by Thomas Mallon. FLORIDIANS IN NEW HAMPSHIRE 21 by Tim Alberta 47 HOLDING UP A MIRROR Jeb and Marco compete. -

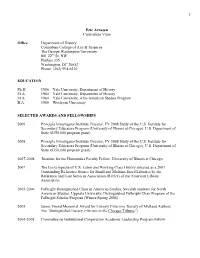

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

The Art of David Gelernter WHEN: Through January 20, 2013 WHERE: Yeshiva University Museum, 15 West 16Th St

For Immediate Release Contact: Michael Kaminer, 212‐260‐9733 [email protected] THE PAINTED WORD: DAVID GELERNTER’S FIRST MUSEUM EXHIBITION BRINGS MESMERIZING “TEXT” PAINTINGS TO YESHIVA UNIVERSITY MUSEUM WHAT: Sh’ma/Listen: The Art of David Gelernter WHEN: Through January 20, 2013 WHERE: Yeshiva University Museum, 15 West 16th St. in Manhattan, 212‐294‐8330 COST: Adults: $8; seniors and students: $6. Free for members and children under 5 WEB: http://yumuseum.tumblr.com/Gelernter or www.yumuseum.org “The central goal of an artist is to create an image that radiates sanctity… that creates an environment, an ambience, a sacred space.” –David Gelernter New York, NY (November 26, 2012) – As a field‐changing computer scientist, author and critic, David Gelernter occupies a unique place in American intellectual life – “at the intersection of technology, art, politics, and religion,” wrote the Seattle Times. Now, people will have the opportunity to experience his work as a painter, which Gelernter describes as his true calling. His images pulsate with energy and color – and with challenging ideas. Yeshiva University Museum, near Union Square, is presenting the first museum exhibition of Gelernter’s entrancing word paintings, based on phrases from the Hebrew Bible, Jewish liturgy and other sources, as well as an arresting series of monumental new works based on Christian tomb sculpture, which capture portraits of the great Hebrew Biblical kings. Sh’ma/Listen: The Art of David Gelernter features 27 paintings and 2 drawings – executed in a striking range of media, including acrylic, oil, pastel, aquarelle (water‐soluble crayons), liquid iron, and gold and metal leaf. -

Neg(Oti)Ating Fusion: Steely Dan's Generic Irony by Ethan Krajewski A

Neg(oti)ating Fusion: Steely Dan’s Generic Irony by Ethan Krajewski A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2018 © 2018 Ethan Patrick Krajewski To my parents for music and language Acknowledgements My biggest thanks go to my advisor, Professor Julian Levinson, as a teacher, mentor, and friend, for helping me think, talk, write, and (most importantly, I think) laugh about seventies rock music. You’ve helped make this project fun in all of its rigor and relaxed despite all of the stress that it’s caused. I’d also like to thank Professor Gillian White for leading our cohort toward discipline, and for keeping us all grounded. Also for her spirited conversations and anecdotes, which proved invaluable in the early stages of my thinking. I wouldn’t be here writing this if it weren’t for Professor Supriya Nair, who pushed me to apply for the program and helped me develop the intellectual curiosity that led to this project. The same goes for Gina Brandolino, who I count among my most important teachers and role models. To the cohort: thank you for all of your help over the course of the year. You’re all so smart, and so kind, and I wish you all nothing but the best. To Ashley: if you aren’t the best non-professional line editor at large in the world, then you’re at least second or third. I mean it sincerely when I say that this project would be infinitely worse without your guidance. -

Publication 2

KHU_playbill_cat.indd 1 6/4/14 2:44 PM Contents FORWARD..............................................4 Rebecca Ruth Hart ANCIENT EVENINGS.........................6 REN..........................................................8 KHU........................................................11 OSIRIS IN DETROIT.............................12 Angus Cook MAP........................................................16 LIBRETTO...........................................20 NOTES ON THE MUSIC...................27 Jonathan Bepler and Shane Anderson PROFILES.............................................28 CAST AND CREW..............................30 WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST.........32 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION.......35 “I believe in the practice and philosophy of what we have agreed to call magic, in what I must call the evocation of spirits, though I do not know what they are, in the power of creating magical illusions, in the visions of truth in the depths of the mind when the eyes are closed; and I believe…that the borders of our mind are ever shifting, and that many minds can flow into one another, as it were, and create or reveal a single mind, a single energy…and that our memories are part of one great memory, the memory of Nature herself.” W.B. Yeats Ideas of Good and Evil Epigraph to Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evenings The use of any recording device, either audio or video, and the taking of photographs, either with or without flash, is strictly prohibited. Please turn cellular phones off, as it interferes with audio recording equipment and telecommunications. Thank you. KHU_playbill_cat.indd 2-1 6/4/14 2:44 PM KHU_playbill_cat.indd 2-3 6/4/14 2:44 PM Forward With the promise of full support from Henry Ford’s son Edsel, William Rebecca Ruth Hart Valentiner, then director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, met with Rivera in San Francisco in 1930. -

The Last 24 Notes MATT LABASH on Bugles Across America

WHAT TO DO ABOUT SYRIA BARNES • GERECHT • KAGAN KRISTOL • SCHMITT • SMITH SEPTEMBER 16, 2013 $4.95 The Last 24 Notes MATT LABASH on Bugles Across America WWEEKLYSTANDARD.COMEEKLYSTANDARD.COM Contents September 16, 2013 • Volume 19, Number 2 2 The Scrapbook We’ll take the disposable Post, the march of science, & more 5 Casual Joseph Bottum gets stuck in the land of honey 7 Editorial The Right Vote BY WILLIAM KRISTOL Articles 9 I Came, I Saw, I Skedaddled BY P. J. O’ROURKE Decisive moments in Barack Obama history 7 10 Do It for the Presidency BY GARY SCHMITT Congress, this time at least, shouldn’t say no to Obama 12 What to Do About Syria BY FREDERICK W. K AGAN Vital U.S. interests are at stake 14 Sorting Out the Opposition to Assad BY LEE SMITH They’re not all jihadist dead-enders 16 Hesitation, Delay, and Unreliability BY FRED BARNES Not the qualities one looks for in a war president 17 The Louisiana GOP Gains a Convert BY MICHAEL WARREN Elbert Lee Guillory, Cajun noir Features 20 The Last 24 Notes BY MATT LABASH Tom Day and the volunteer buglers who play ‘Taps’ at veterans’ funerals across America 26 The Muddle East BY REUEL MARC GERECHT Every idea Obama had about pacifying the Muslim world turned out to be wrong Books & Arts 9 30 Winston in Focus BY ANDREW ROBERTS A great man gets a second look 32 Indivisible Man BY EDWIN M. YODER JR. Albert Murray, 1916-2013 33 Classical Revival BY MARK FALCOFF Germany breaks from its past to embrace the past 36 Living in Vein BY JOSHUA GELERNTER Remember the man who invented modern medicine 37 With a Grain of Salt BY ELI LEHRER Who and what, exactly, is the chef du jour? 39 Still Small Voice BY JOHN PODHORETZ Sundance gives birth to yet another meh-sterpiece 20 40 Parody And in Russia, the sun revolves around us COVER: An honor guard bugler plays at the burial of U.S. -

81 Norman Mailer

UDK 821.111(73)–311.6.09Mailer N. NOrMAN MAIlEr - ThE MOST INFlUENTIAl CrITIC OF CONTEMPOrArY rEAlITY IN ThE SECOND hAlF OF ThE TwENTIETh CENTUrY Jasna Potočnik Topler Abstract Norman Mailer, one of the most influential authors of the second half of the twentieth century, faithfully followed his principle that a writer should also be a critic of contemporary reality. Therefore, most of his works portray the reality of the United States of America and the complexities of the contemporary American scene. Mailer described the spirit of his time – from the terror of war and numerous dynamic social and political processes to the 1969 moon landing. Conflicts were often in the centre of his writing, as was the relationship between an individual and the society; he speaks of political power and the dangerous power of capital, while pointing to the threat of totalitarianism in America. Mailer spent his entire career writing about violence, power, perverted sexuality, the phenomenon of Hitler, terrorism, religion and corruption. He continually pointed out that individuals were in constant danger of losing freedom and dignity. keywords: American novel, political power, Norman Mailer, literary journalism Norman Kingsley Mailer, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and journalist, and one of the most influential authors of the second half of the twentieth century, faithfully followed his principle that a writer should also be a critic of contemporary reality. One of his biogra- phers Mary V. Dearborn wrote, »In the case of Norman Mailer, the man and his life are of equal, often competing stature with his work, and it is for his life as well as his work that he will be remembered« (Dearborn 8). -

Reincarnation of Norman I

Architecture and Naturing Affairs 264 Reincarnation of Norman I About Life in Repeated Embodiments Living new lives, in a cycle: whereas Orlando in Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel wakes up as a different gender regularly, effortlessly, and seamlessly, in Matthew Barney’s film-opera, River of Fundament (2014) the protag- onist Norman is transmogrified through much more ritual-intensive and sculptural transformations. Inspired by Norman Mailer’s novel Ancient Evenings (1983), then replacing the protagonist (an ancient Egyptian noble- man Menenhetet I) with the author of the novel himself, Barney’s film begins with the ka spirit of Norman ascending from the underworld. Norman is reincarnated as Norman I and Norman II over five hours. Sleek automo- tive corpses embody them: a 1967 Chrysler Crown Imperial, a 1979 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am, a 2001 Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptor. Along- side those, primitive materials such as lead and zinc turn into iron and copper, bronze and brass, then toward silver and gold. A glimpse at one of the most powerful scenes of River of Fundament, in which the molten Pontiac Trans Am is cast into a massive iron pillar (DJED), impregnating the spirit of Norman II: 265 III Inhabiting L I B R E T T O Casting Pit, Detroit Steel Plant: The Body of Osiris FULL CAST AND ENSEMBLE IRON WORKERS NELPHTHYS (Jennie Knaggs, mezzo-soprano) BELITA WOODS (Contralto) 5 JAMES LEE BYARS 3 TRASH CONTAINER PERCUSSIONISTS 6 LONG STRING PLAYERS 1 VULTURE ISIS has been locked in the back of the CROWN VICTORIA, which drives up a long ramp to an embankment wall overlooking a deep excavated pit.