PURCELL Ode for St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heresa Caudle Violin, Corne� (Tracks 3, 4, 6, 9, 11–13 & 17) Biagio Marini Steven Devine Organ, Harpsichord (All Tracks) Biagio Marini 15

Dario Castello (fl. 1st half 17th century) Ignazio Dona (c.1570–1638) Venice 1629 1. Sonata terza [b] [5:41] 11. Maria Virgo [a]* [4:04] Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) Alessandro Grandi 2. Exulta, filia Sion [a] [5:19] 12. Salva me, salutaris Hosa [a]* [3:43] The Gonzaga Band Biagio Marini (1594–1663) Benedeo Rè (fl. 1607–1629) 3. Canzon prima, 13. Lilia convallium [a]* [3:40] Faye Newton soprano (tracks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10–13 & 16) per quaro violini, ò corne [e] [3:12] Jamie Savan director, cornes (treble, mute, tenor) (tracks 1, 3, 5, 10–13 & 15–17) Marno Pesen Helen Roberts corne (tracks 1, 3, 11, 16 & 17) Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672) 14. Corrente dea La Priula [f]* [2:13] Oliver Webber violin (tracks 3, 4, 6, 9, 12–13, 15 & 17) 4. Paratum cor meum [g] [4:22] Theresa Caudle violin, corne (tracks 3, 4, 6, 9, 11–13 & 17) Biagio Marini Steven Devine organ, harpsichord (all tracks) Biagio Marini 15. Sonata senza cadenza [e] [3:04] 5. Sonata per l’organo, violino, ò corneo [e] [3:47] Heinrich Schütz 16. Exultavit cor meum [g] [5:20] Alessandro Grandi (1586–1630) 6. Regina caeli [d] [3:04] Dario Castello 17. Sonata decima sema, Marno Pesen (c.1600–c.1648) in ecco [b] [7:15] 7. Corrente dea La Granda [f]* [2:00] Orazio Tardi (1602–1677) Total playing me [68:27] 8. Plaudite, cantate [h]* [4:32] About The Gonzaga Band: Biagio Marini * world premiere recording ‘Faye Newton sings delightfully, and the players – 9. -

Metamorphosis a Pedagocial Phenomenology of Music, Ethics and Philosophy

METAMORPHOSIS A PEDAGOCIAL PHENOMENOLOGY OF MUSIC, ETHICS AND PHILOSOPHY by Catalin Ursu Masters in Music Composition, Conducting and Music Education, Bucharest Conservatory of Music, Romania, 1983 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Faculty of Education © Catalin Ursu 2009 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall, 2009 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the “Institutional Repository” link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Musica Britannica

T69 (2021) MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens c.1750 Stainer & Bell Ltd, Victoria House, 23 Gruneisen Road, London N3 ILS England Telephone : +44 (0) 20 8343 3303 email: [email protected] www.stainer.co.uk MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Musica Britannica, founded in 1951 as a national record of the British contribution to music, is today recognised as one of the world’s outstanding library collections, with an unrivalled range and authority making it an indispensable resource both for performers and scholars. This catalogue provides a full listing of volumes with a brief description of contents. Full lists of contents can be obtained by quoting the CON or ASK sheet number given. Where performing material is shown as available for rental full details are given in our Rental Catalogue (T66) which may be obtained by contacting our Hire Library Manager. This catalogue is also available online at www.stainer.co.uk. Many of the Chamber Music volumes have performing parts available separately and you will find these listed in the section at the end of this catalogue. This section also lists other offprints and popular performing editions available for sale. If you do not see what you require listed in this section we can also offer authorised photocopies of any individual items published in the series through our ‘Made- to-Order’ service. Our Archive Department will be pleased to help with enquiries and requests. In addition, choirs now have the opportunity to purchase individual choral titles from selected volumes of the series as Adobe Acrobat PDF files via the Stainer & Bell website. -

Handel's Last Prima Donna

SUPER AUDIO CD HANDEL’s LAST PRIMA DONNA GIULIA FRASI IN LONDON RUBY HUGHES Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment LAURENCE CUMMINGS CHANDOS early music John Christopher Smith, c.1763 Smith, Christopher John Etching, published 1799, by Edward Harding (1755 – 1840), after portrait by Johan Joseph Zoffany (1733 – 1810) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Handel’s last prima donna: Giulia Frasi in London George Frideric Handel (1685 – 1759) 1 Susanna: Crystal streams in murmurs flowing 8:14 Air from Act II, Scene 2 of the three-act oratorio Susanna, HWV 66 (1749) Andante larghetto e mezzo piano Vincenzo Ciampi (?1719 – 1762) premiere recording 2 Emirena: O Dio! Mancar mi sento 8:35 Aria from Act III, Scene 7 of the three-act ‘dramma per musica’ Adriano in Siria (1750) Edited by David Vickers Cantabile – Allegretto premiere recording 3 Camilla: Là per l’ombrosa sponda 4:39 Aria from Act II, Scene 1 of the ‘dramma per musica’ Il trionfo di Camilla (1750) Edited by David Vickers [ ] 3 Thomas Augustine Arne (1710 – 1778) 4 Arbaces: Why is death for ever late 2:21 Air from Act III, Scene 1 of the three-act serious opera Artaxerxes (1762) Sung by Giulia Frasi in the 1769 revival Edited by David Vickers [Larghetto] John Christopher Smith (1712 – 1795) 5 Eve: Oh! do not, Adam, exercise on me thy hatred – 1:02 6 It comes! it comes! it must be death! 5:45 Accompanied recitative and song from Act III of the three-act oratorio Paradise Lost (1760) Edited by David Vickers Largo – Largo premiere recording 7 Rebecca: But see, the night with silent pace -

Music and Elite Identity in the English Country House, C. 1790-1840

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Music Music and Elite Identity in the English Country House, c.1790-1840 by Leena Asha Rana Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 2 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Music Doctor of Philosophy MUSIC AND ELITE IDENTITY IN THE ENGLISH COUNTRY HOUSE, c.1790-1840. by Leena Asha Rana In this thesis I investigate two untapped music book collections that belonged to two women. Elizabeth Sykes Egerton (1777-1853) and Lydia Hoare Acland (1786-1856) lived at Tatton Park, Cheshire, and Killerton House, Devon, respectively. Upon their marriage in the early nineteenth century, they brought with them the music books they had compiled so far to their new homes, and they continued to collect and play music after marriage. -

Annotated Bibliography of Renaissance Dance This Bibliography Is the Joint Effort of Many Subscribers to the RENDANCE Electronic Mailing List

Bibliography 1 Annotated Bibliography of Renaissance Dance This bibliography is the joint effort of many subscribers to the RENDANCE electronic mailing list. It may be copied and freely distributed for no commercial gain. It may not be sold or included in collections to be sold for a profit. A small fee to cover copying costs is permissible. The compiler claims no responsibility for the correctness or usefulness of any of the information contained in this bibliography, and shall not be liable for damages arising from the use or misuse of the material contained herein. Since the original edition, a couple of on-line editions have appeared. This copy was compiled from one produced by Andrew Draskoy, using a web based bibliography package that he wrote. Additional code to convert the database to this format was written by myself. Some transcription errors may have occurred in the conversion – notably I had some difficulties converting some of the international characters used (e.g: é, ç, ü, etc) into the format used by OpenOffice, and so I apologise for any errors that were introduced in this stage. Hopefully Andrew's on-line edition will be released for public usage shortly but at the moment it only exists on a private server. Books & Articles (author unknown). fonds fr. 5699. , formerly fonds fr. 10279. , Le ballet de la royne de Cessile. Matt Larsen: Flyleaf choreographies to a copy of Geste des nobles Francoys in Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale. Dances transcribed in Sachs, pp. 313-314. This document lists the dances which were performed at a court function in 1445, and includes the choreographies for each dance. -

Figures Followed by an Asterisk Rifer to an Auction-Price Paid Jor a Musical Work Or Other Item

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-15743-8 - Some British Collectors of Music c. 1600–1960 A. Hyatt King Index More information INDEX Figures followed by an asterisk rifer to an auction-price paid Jor a musical work or other item. Figures in bold type refer to the location of an auction sale-catalogue or to evidence that a sale took place. Abel, Carl Friedrich, 107 Andre, Johann Anton, 46 Aberdeen University, collection of William Andrews, Hilda, 103 Lawrence Taylor bequeathed to, 87, 146 Angel, Alfred, collection sold, 138 (1876) Aberdeen University Studies, 87 n. Anglebert, Jean Baptiste Henri d' Academy of Ancient Music, 16, 31, 147 performer in Ballet de la naissance de Venus, 65 Additions to the Manuscripts of the British Museum, Pieces de clavecin, 65 1846-1847, 44 n. Anne, Q!!een, 65 Adelaide, Q!!een Consort of William IV, !I2 n. Anselmi, Giorgio, 40 Adlung, Jacob, 81 Anselms, see Anselmi, Giorgio Adolphus Frederick, Duke of Cambridge, 95 Apel, Willi, 21 'catalogue thematique', 48 Apollo, The, 29 collection described, 48; sold, 136 (1850) Araja, Francesco, autographs in Royal Music Adson, John, Courtly masquing Ayres, 95* Library, 108 Agricola, Martin, 8 I Archadelt, Jacob, Primo libro de' madrigali, 56* 'Airiettes', 28, 45 Archbishop Marsh's Library, see Dublin Albert, Prince Consort, 92 n. Ariosti, Attilio, 106 as collector, !I2 Aristoxenus, Harmonicorum elementorum libri III, library stamp, !I3 56 Alcock, John, the elder, 148 Arkwright, Godfrey Edward Pellew, 96, 128 n. Alderson, Montague Frederick, 67 n. collection described, 74, 75; sold, 141 (1939, Aldrich, Henry, 90 1944) collection bequeathed to Christ Church, Oxford, Catalogue ofMusic in the Library of Christ Church, 13, 145; catalogue of, by J. -

Download Concert Programme

Th ursday 7 November 2019, 7.30pm Cadogan Hall, Sloane Terrace, SW1 Celebrating 60 years PURCELL KING ARTHUR CONCERT PERFORMANCE Programme £3 Welcome to Cadogan Hall Please note: • Latecomers will only be admitted to the auditorium during a suitable pause in the performance. • All areas of Cadogan Hall are non-smoking areas. • Glasses, bottles and food are not allowed in the auditorium. • Photography, and the use of any video or audio recording equipment, is forbidden. PURCELL • Mobiles, Pagers & Watches: please ensure that you switch off your mobile phone and pager, and deactivate any digital alarm on your watch before the performance begins. • First Aid: Please ask a Steward if you require assistance. • Thank you for your co-operation. We hope you enjoy the concert. Programme notes adapted from those by Michael Greenhalgh, facebook.com/ by permission of Harmonia Mundi. londonconcertchoir Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie instagram.com/ London Concert Choir is a company limited by guarantee, londonconcertchoir incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 @ChoirLCC Registered Office: 7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU Thursday 7 November 2019 Cadogan Hall PURCELL KING ARTHUR CONCERT PERFORMANCE Mark Forkgen conductor Rachel Elliott soprano Rebecca Outram soprano Bethany Partridge soprano William Towers counter tenor James Way tenor Peter Willcock bass baritone Aisling Turner and Joe Pike narrators London Concert Choir Counterpoint Ensemble There will be an interval of 20 minutes after ACT III Henry Purcell (1659–1695) King Arthur Semi-opera in five acts Libretto by John Dryden The first concert in the choir’s 60th Anniversary season is Purcell’s dramatic masterpiece about the conflict between King Arthur’s Britons and the heathen Saxon invaders. -

Choral Music 2020

T60 Choral Music 2020 STA INER & BE LL LTD PO Box 110, Victoria House, 23 Gruneisen Road, London N3 1DZ Including the editions of Telephone: +44 (0) 20 8343 3303 email: [email protected] https://stainer.co.uk AUGENER � GALLIARD � WEEKES � JOSEPH WILLIAMS CHORAL MUSIC Contents Ordering Information.................................................................................2 Anthems and Services..............................................................................3 Christmas Music, Carols and Spirituals ....................................................8 Madrigals, Airs and Partsongs ................................................................12 Mixed Voices ..........................................................................................15 High Voices.............................................................................................19 Male Voices ............................................................................................20 For Children ............................................................................................20 Library Editions: ......................................................................................21 The Byrd Edition ................................................................................21 Early English Church Music ..............................................................21 Musica Britannica ..............................................................................22 Purcell Society Edition ......................................................................23 -

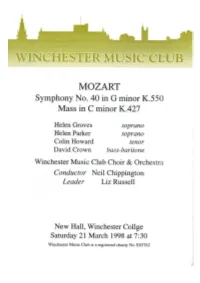

1998 Spring Programme

Symphony No.40 in G minor K.550 It is unclear exactly why Mozart wrote his final three symphonies (numbers 39, 40 and 41), but they were completed within the space of six weeks during June, July and August of 1788. This was some two years after he had written the "Prague" symphony (number 38), and it may be that he regarded these three works as his last fling at the genre. The G minor symphony is different in mood to its two symphonic neighbours. There is a passionate quality to this work that is far removed from the joie de vivre of number 39, for example. It is its restlessness, though, which strikes the listener from the outset during an unusually quiet opening. The second movement has a rare intensity of expression, and even the rhythmically based last movement has a serious nature to it. I hope you feel that it makes a fitting prelude to the C minor Mass. Mass in C minor K.427 Mozart promised to write a mass in celebration of his marriage to Constanze Weber on August 4th 1782. The idea was to perform the work in Salzburg when the newly weds visited Mozart's father and sister. This indeed happened and the work, which consisted of only four movements (Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus and Benedictus), was first performed in St. Peter's, Salzburg on October 26th 1783. Mozart never completed the mass, although he had drafted two sections of the Credo, and you will hear a completion of these tonight along with Mozart's four completed movements. -

10A Fuller CD Labels

Music 10A CD 1 1. Easter Mass Introit Resurrexi (1a, p.2). Benedictine Monks 5:50 2. Alleluia Pascha nostrum (1f, p.9). Benedictine Monks 2:20 3. Rex caeli Domine (4a., p.32). Pro Cantione Antiqua :30 4. Sit gloriaDomini (4b., p.33) :30 5. Wulfstan of Winchester Alleluia Te martyrum (5, p. 35). Pro Cantione Antiqua 2:00 6. Antiphon Ave regina caelorum (7a, p. 38). Schola Cantorum Francesco Coradini 1:24 *7. Hildegard of Bingen O quam mirabilis est (Antiphon). Sequentia,Jill Feldman, sop. 2:37 *8. Hildegard of Bingen O virtus sapientiae (Antiphon). Sequentia 2:47 *NOT IN ANTHOLOGY 9. Bernart de Ventadorn Can vei la lauzeta mover (8a, p.42). Paul Hillier 2:45 10. Gaucelm Faidit Fortz chausa es (8c, p.45). Verses 1 and 7 only. 5:30 11. Gace Brulé Biaus m'est estez (8e, p.49) Verses 1 and 3 only. Studio der frühen Musik 4:34 12. Leonin Alleluia Pascha nostrum , first 4 lines (10a,p.58) 1:44 13. Leonin revision 10b continues from 10a, p.60). Capella Antiqua of Munich 4:16 14. Perotin Alleluia Pascha nostrum (11, p.67). Capella Antiqua of Munich 3:00 15. Deus in Adjutorium (12a, p.74). Capella Antiqua of Munich 1:50 16. Ad solitum vomitum/Regnat a 2 (13b, p.78) :57 17. Ad solitum vomitum/Regnat a 3 (13c) :56 18. Depositum creditum/Ad solitum/Regnat (13d, p.80). Capella Antiqua of Munich 1:00 19. L'autre jour/Au tens pascour/In seculum (13f, p.83). Pro Musica Antiqua 3:10 20. -

Samuel Howard and the Music for the Installation of the Duke of Grafton As Chancellor of Cambridge University, 1769 Alan Howard

SAMUEL HOWARD AND THE MUSIC FOR THE INSTALLATION OF THE DUKE OF GRAFTON AS CHANCELLOR OF CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY, 1769 ALAN HOWARD ABSTRACT Samuel Howard (?1710–1782) has long been a familiar inhabitant of the diligent footnotes of Handel biographers. A choirboy in the Chapel Royal, he was a member of Handel’s chorus and the composer of much theatre music of his own; he later became organist of both St Bride’s, Fleet Street and nearby St Clement Danes, Strand, where he was buried in 1782. His most significant and ambitious work is his fine orchestrally accompanied anthem ‘This is the day which the Lord hath made’, published posthumously in 1792 with an impressive title page detailing the performance of the work ‘at St Margaret’s Church before the governors of the Westminster Infirmary, in the Two Universities, and upon many other Publick Occasions in different parts of the Kingdom’. This article confirms for the first time that this work originated as Howard’s doctoral exercise, drawing on contemporary press reports and information in the University archives; together these make clear that the composer’s doctorate was linked to the provision of music for the Duke of Grafton’s installation as Chancellor in 1769. Surviving information about this event offers a glimpse of musical life in Cambridge on a comparable scale to the much better reported proceedings upon similar occasions in Oxford. This evidence then serves as a starting point from which to consider Howard’s later prominence as a director of high-profile public performances in London and the provinces.