English Business Organization Law During the Industrial Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

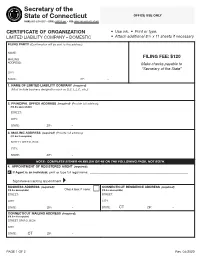

Certificate of Organization (LLC

Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] • WEB: www.concord-sots.ct.gov CERTIFICATE OF ORGANIZATION • Use ink. • Print or type. LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY – DOMESTIC • Attach additional 8 ½ x 11 sheets if necessary. FILING PARTY (Confirmation will be sent to this address): NAME: FILING FEE: $120 MAILING ADDRESS: Make checks payable to “Secretary of the State” CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 1. NAME OF LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY (required) (Must include business designation such as LLC, L.L.C., etc.): 2. PRINCIPAL OFFICE ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 3. MAILING ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – NOTE: COMPLETE EITHER 4A BELOW OR 4B ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE, NOT BOTH. 4. APPOINTMENT OF REGISTERED AGENT (required): A. If Agent is an individual, print or type full legal name: _______________________________________________________________ Signature accepting appointment ▸ ____________________________________________________________________________________ BUSINESS ADDRESS (required): CONNECTICUT RESIDENCE ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box unacceptable) Check box if none: (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: STREET: CITY: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – STATE: CT ZIP: – CONNECTICUT MAILING ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: CT ZIP: – PAGE 1 OF 2 Rev. 04/2020 Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] -

Partnership Management & Project Portfolio Management

Partnership Management & Project Portfolio Management Partnerships and strategic management for projects, programs, quasi- projects, and operational activities In the digital age – we need appropriate socio-technical approaches, tools, and methods for: • Maintainability • Sustainability • Integration • Maturing our work activities At the conclusion of this one-hour session, participants will: • Be able to define partnership management and project portfolio management. • Be able to identify examples of governance models to support partnerships. • Be able to share examples of document/resource types for defining and managing partnerships within project portfolio management. • Be able to describe how equity relates to partnerships and partnership management. Provider, Partner, Pioneer Digital Scholarship and Research Libraries Provider, Partner, Pilgrim (those who journey, who wander and wonder) https://www.rluk.ac.uk/provider-partner-pioneer-digital-scholarship-and-the-role-of-the-research-library-symposium/ Partners and Partnership Management Partner: any individual, group or institution including governments and donors whose active participation and support are essential for the successful implementation of a project or program. Partnership Management: the process of following up on and maintaining effective, productive, and harmonious relationships with partners. It can be informal (phone, email, visits) or formal (written, signed agreements, with periodic review). What is most important is to: invest the time and resources needed to -

Organizational Culture Model

A MODEL of ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE By Don Arendt – Dec. 2008 In discussions on the subjects of system safety and safety management, we hear a lot about “safety culture,” but less is said about how these concepts relate to things we can observe, test, and manage. The model in the diagram below can be used to illustrate components of the system, psychological elements of the people in the system and their individual and collective behaviors in terms of system performance. This model is based on work started by Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura in the 1970’s. It’s also featured in E. Scott Geller’s text, The Psychology of Safety Handbook. Bandura called the interaction between these elements “reciprocal determinism.” We don’t need to know that but it basically means that the elements in the system can cause each other. One element can affect the others or be affected by the others. System and Environment The first element we should consider is the system/environment element. This is where the processes of the SMS “live.” This is also the most tangible of the elements and the one that can be most directly affected by management actions. The organization’s policy, organizational structure, accountability frameworks, procedures, controls, facilities, equipment, and software that make up the workplace conditions under which employees work all reside in this element. Elements of the operational environment such as markets, industry standards, legal and regulatory frameworks, and business relations such as contracts and alliances also affect the make up part of the system’s environment. These elements together form the vital underpinnings of this thing we call “culture.” Psychology The next element, the psychological element, concerns how the people in the organization think and feel about various aspects of organizational performance, including safety. -

Partnership Agreement Example

Partnership Agreement Example THIS PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT is made this __________ day of ___________, 20__, by and between the following individuals: Address: __________________________ ___________________________ City/State/ZIP:______________________ Address: __________________________ ___________________________ City/State/ZIP:______________________ 1. Nature of Business. The partners listed above hereby agree that they shall be considered partners in business for the following purpose: ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ 2. Name. The partnership shall be conducted under the name of ________________ and shall maintain offices at [STREET ADDRESS], [CITY, STATE, ZIP]. 3. Day-To-Day Operation. The partners shall provide their full-time services and best efforts on behalf of the partnership. No partner shall receive a salary for services rendered to the partnership. Each partner shall have equal rights to manage and control the partnership and its business. Should there be differences between the partners concerning ordinary business matters, a decision shall be made by unanimous vote. It is understood that the partners may elect one of the partners to conduct the day-to-day business of the partnership; however, no partner shall be able to bind the partnership by act or contract to any liability exceeding $_________ without the prior written consent of each partner. 4. Capital Contribution. The capital contribution of -

Limited Liability Partnerships

inbrief Limited Liability Partnerships Inside Key features Incorporation and administration Members’ Agreements Taxation inbrief Introduction Key features • any members’ agreement is a confidential Introduction document; and It first became possible to incorporate limited Originally conceived as a vehicle liability partnerships (“LLPs”) in the UK in 2001 • the accounting and filing requirements are for use by professional practices to after the Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2000 essentially the same as those for a company. obtain the benefit of limited liability came into force. LLPs have an interesting An LLP can be incorporated with two or more background. In the late 1990s some of the major while retaining the tax advantages of members. A company can be a member of an UK accountancy firms faced big negligence claims a partnership, LLPs have a far wider LLP. As noted, it is a distinct legal entity from its and were experiencing a difficult market for use as is evidenced by their increasing members and, accordingly, can contract and own professional indemnity insurance. Their lobbying property in its own right. In this respect, as in popularity as an alternative business of the Government led to the introduction of many others, an LLP is more akin to a company vehicle in a wide range of sectors. the Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2000 which than a partnership. The members of an LLP, like gave birth to the LLP as a new business vehicle in the shareholders of a company, have limited the UK. LLPs were originally seen as vehicles for liability. As he is an agent, when a member professional services partnerships as demonstrated contracts on behalf of the LLP, he binds the LLP as by the almost immediate conversion of the major a director would bind a company. -

Basic Concepts Page 1 PARTNERSHIP ACCOUNTING

Dr. M. D. Chase Long Beach State University Advanced Accounting 1305-87B Partnership Accounting: Basic Concepts Page 1 PARTNERSHIP ACCOUNTING I. Basic Concepts of Partnership Accounting A. What is A Partnership?: An association of two or more persons to carry on as co-owners of a business for a profit; the basic rules of partnerships were defined by Congress: 1. Uniform Partnership Act of 1914 (general partnerships) 2. Uniform Limited Partnership Act of 1916 (limited partnerships) B. Characteristics of a Partnership: 1. Limited Life--dissolved by death, retirement, incapacity, bankruptcy etc 2. Mutual agency--partners are bound by each others’ acts 3. Unlimited Liability of the partners--the partnership is not a legal or taxable entity and therefore all debts and legal matters are the responsibility of the partners. 4. Co-ownership of partnership assets--all assets contributed to the partnership are owned by the individual partners in accordance with the terms of the partnership agreement; or equally if no agreement exists. C. The Partnership Agreement: A contract (oral or written) which can be used to modify the general partnership rules; partnership agreements at a minimum should cover the following: 1. Names or Partners and Partnership; 2. Effective date of the partnership contract and date of termination if applicable; 3. Nature of the business; 4. Place of business operations; 5. Amount of each partners capital and the valuation of each asset contributed and date the valuation was made; 6. Rights and responsibilities of each partner; 7. Dates of partnership accounting period; minimum capital investments for each partner and methods of determining equity balances (average, weighted average, year-end etc.) 8. -

Limited Partnerships

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND TRANSACTIONAL LAW CLINIC LIMITED PARTNERSHIPS INTRODUCTORY OVERVIEW A limited partnership is a business entity comprised of two or more persons, with one or more general partners and one or more limited partners. A limited partnership differs from a general partnership in the amount of control and liability each partner has. Limited partnerships are governed by the Virginia Revised Uniform Partnership Act,1 which is an adaptation of the 1976 Revised Uniform Limited Partnership Act, or RULPA, and its subsequent amendments. HOW A LIMITED PARTNERSHIP IS FORMED To form a limited partnership in Virginia, a certificate of limited partnership must be filed with the Virginia State Corporation Commission. This is different from general partnerships which require no formal recording with the Commonwealth. The certificate must state the name of the partnership,2 and, the name must contain the designation “limited partnership,” “a limited partnership,” “L.P.,” or “LP;” which puts third parties on notice of the limited liability of one or more partners. 3 Additionally, the certificate must name a registered agent for service of process, state the Post Office mailing address of the company, and state the name and address of every general partner. The limited partnership is formed on the date of filing of the certificate unless a later date is specified in the certificate.4 1 VA. CODE ANN. § 50, Ch. 2.2. 2 VA. CODE ANN. § 50-73.11(A)(1). 3 VA. CODE ANN. § 50-73.2. 4 VA. CODE ANN. § 50-73.11(C)0). GENERAL PARTNERS General partners run the company's day-to-day operations and hold management control. -

Effects of Partner Characteristic, Partnership Quality, and Partnership Closeness on Cooperative Performance: a Study of Supply Chains in High-Tech Industry

Management Review: An International Journal Volume 4 Number 2 Winter 2009 Effects of Partner Characteristic, Partnership Quality, and Partnership Closeness on Cooperative Performance: A Study of Supply Chains in High-tech Industry Mei-Ying Wu Department of Information Management Chung-Hua University Hsin-Chu Taiwan, Republic of China Email: [email protected] Yun-Ju Chang Department of Information Management Chung-Hua University Hsin-Chu Taiwan, Republic of China Email: [email protected] Yung-Chien Weng Department of Information Management Chung-Hua University Hsin-Chu Taiwan, Republic of China Email: [email protected] Received May 28, 2009; Revised Aug. 14, 2009; Accepted Oct. 21, 2009 ABSTRACT Owing to the rapid development of information technology, change of supply chain structures, trend of globalization, and intense competition 29 Management Review: An International Journal Volume 4 Number 2 Winter 2009 in the business environment, almost all enterprises have been confronted with unprecedented challenges in recent years. As a coping strategy, many of them have gradually viewed suppliers as “cooperative partners”. They drop the conventional strategy of cooperating with numerous suppliers and build close partnerships with only a small number of selected suppliers. This paper aims to explore partnerships between manufacturers and suppliers in Taiwan’s high- tech industry. Through a review of literature, four constructs, including partner characteristic, partnership quality, partnership closeness, and cooperative performance are extracted to be the basis of the research framework, hypotheses, and questionnaire. The questionnaire is administered to staff of the purchasing and quality control departments in some high-tech companies in Taiwan. The proposed hypotheses are later empirically validated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM). -

Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-2019 Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship Jacob Martin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Martin, Jacob, "Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship" (2019). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 124. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. This dissertation, directed and approved by the candidate’s committee, has been accepted by the College of Graduate and Professional Studies of Abilene Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership Dr. Joey Cope, Dean of the College of Graduate and Professional Studies Date Dissertation Committee: Dr. First Name Last Name, Chair Dr. First Name Last Name Dr. First Name Last Name Abilene Christian University School of Educational Leadership Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership by Jacob Martin December 2018 i Acknowledgments I would not have been able to complete this journey without the support of my family. My wife, Christal, has especially been supportive, and I greatly appreciate her patience with the many hours this has taken over the last few years. I also owe gratitude for the extra push and timely encouragement from my parents, Joe Don and Janet, and my granddad Dee. -

ACCOUNTING for PARTNERSHIPS and LIMITED LIABILITY CORPORATIONS Objectives

13 ACCOUNTING FOR PARTNERSHIPS AND LIMITED LIABILITY CORPORATIONS objectives After studying this chapter, you should be able to: Describe the basic characteristics of 1 proprietorships, corporations, partner- ships, and limited liability corpora- tions. Describe and illustrate the equity re- 2 porting for proprietorships, corpora- tions, partnerships, and limited liability corporations. Describe and illustrate the accounting 3 for forming a partnership. Describe and illustrate the accounting 4 for dividing the net income and net loss of a partnership. Describe and illustrate the accounting 5 for the dissolution of a partnership. Describe and illustrate the accounting 6 for liquidating a partnership. Describe the life cycle of a business, 7 including the role of venture capital- ists, initial public offerings, and under- writers. PHOTO: © EBBY MAY/STONE/GETTY IMAGES IIf you were to start up any type of business, you would want to separate the busi- ness’s affairs from your personal affairs. Keeping business transactions separate from personal transactions aids business analysis and simplifies tax reporting. For example, if you provided freelance photography services, you would want to keep a business checking account for depositing receipts for services rendered and writing checks for expenses. At the end of the year, you would have a basis for determining the earn- ings from your business and the information necessary for completing your tax re- turn. In this case, forming the business would be as simple as establishing a name and a separate checking account. As a business becomes more complex, the form of the business entity becomes an important consideration. The entity form has an im- pact on the owners’ legal liability, taxation, and the ability to raise capital. -

The Federal Definition of Tax Partnership

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship Winter 2006 The edeF ral Definition of Tax Partnership Bradley T. Borden [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Other Law Commons, Taxation-Federal Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation 43 Hous. L. Rev. 925 (2006-2007) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLE THE FEDERAL DEFINITION OF TAX PARTNERSHIP Bradley T. Borden* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODU CTION ...................................................................... 927 II. THE DEFINITIONS OF MULTIMEMBER TAx ENTITIES ............ 933 A. The EstablishedDefinitions .......................................... 933 B. The Open Definition: Tax Partnership......................... 936 III. HISTORY AND PURPOSE OF PARTNERSHIP TAXATION ............ 941 A. The Effort to Disregard................................................. 941 B. The Imposition of Tax Reporting Requirements ........... 943 C. The Statutory Definition of Tax Partnership............... 946 D. The 1954 Code: An Amalgam of the Entity and Aggregate Theories........................................................ 948 E. The Section 704(b) Allocation Rules and Assignment of Incom e ....................................................................... 951 F. The Anti-Abuse Rules .................................................... 956 * Associate Professor of Law, Washburn University School of Law, Topeka, Kansas; LL.M. and J.D., University of Florida Levin College of Law; M.B.A. and B.B.A., Idaho State University. I thank Steven A. Bank, Stanley L. Blend, Terrence F. Cuff, Steven Dean, Alex Glashausser, Christopher Hanna, Brant J. Hellwig, Dennis R. Honabach, Erik M. Jensen, L. Ali Khan, Martin J. McMahon, Jr., Stephen W. Mazza, William G. Merkel, Robert J. Rhee, William Rich, and Ira B. -

A Guide to Nonprofit Board Service in Oregon

A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE IN OREGON Office of the Attorney General A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE Dear Board Member: Thank you for serving as a director of a nonprofit charitable corporation. Oregonians rely heavily on charitable corporations to provide many public benefits, and our quality of life is dependent upon the many volunteer directors who are willing to give of their time and talents. Although charitable corporations vary a great deal in size, structure and mission, there are a number of principles which apply to all such organizations. This guide is provided by the Attorney General’s office to assist board members in performing these important functions. It is only a guide and is not meant to suggest the exact manner that board members must act in all situations. Specific legal questions should be directed to your attorney. Nevertheless, we believe that this guide will help you understand the three “R”s associated with your board participation: your role, your rights, and your responsibilities. Active participation in charitable causes is critical to improving the quality of life for all Oregonians. On behalf of the public, I appreciate your dedicated service. Sincerely, Ellen F. Rosenblum Attorney General 1 UNDERSTANDING YOUR ROLE Board members are recruited for a variety of reasons. Some individuals are talented fundraisers and are sought by charities for that reason. Others bring credibility and prestige to an organization. But whatever the other reasons for service, the principal role of the board member is stewardship. The directors of the corporation are ultimately responsible for the management of the affairs of the charity.