Bulletin #292

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chessproblems.Ca 2013 Award – by Ivan Skoba I Would first Like to Thank Cornel for Inviting Me to Judge This Section 1: Series Records & Long-Movers (15) Tournament

...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA Contents . ISSUE 3 (SEPTEMBER 2014) Page 1 Originals 73 2014 Informal Tourney....... 73 2 Chess Chat 75 with Adrian Storisteanu....... 75 3 Articles 79 Arno T¨ungler: Series-Castling Length Records........ 79 4 2013 Award 80 by Ivan Skoba............ 80 Section 1............ 80 Section 2............ 83 5 ChessProblems.ca TT6 87 6 Selected Compositions 88 Series Retractors........... 88 72. f-Thematurnier......... 90 Rex-Solus Challenge 2014...... 91 Messigny 2012 Fairies Award.... 93 7 Last Page 95 Canadian Chess Chat........ 95 Editor: Cornel Pacurar Originals: [email protected] Articles: [email protected] Correspondence: [email protected] Isolated Pawn [Watercolour, c Elke Rehder, http://www.elke-rehder.de. Reproduced with permission.] ISSN 2292-8324 ..... ChessProblems.ca Bulletin IIssue 3I ORIGINALS 2014 Informal Tourney T185 S´ebastienLuce T186 T187 T188 Pierre Tritten S´ebastienLuce S´ebastienLuce Karol Mlynka ChessProblems.ca's annual Informal Tourney ¡¥" U is open for series-movers of any type and with any fairy conditions and pieces. # L Hors concours compositions (any genre) £ are also welcome! Send to: [email protected]. # £¢# ! T 2014 Judge: Nicolas Dupont (FRA) C+ (1+14)ser-=50 C+ (16+1)ser-h#48 C+ (1+16)ser-=46 C+ (1+2)ser-h#10 AntiCirce Couscous Rifle Chess Rifle Chess L 2014 Tourney Participants: T = Locust 1. Alberto Armeni (ITA) U = Royal Pawn 2. Geoff Foster (AUS) = 2,5-Leaper 3. Harald Grubert (DEU) 4. Georgi Hadˇzi-Vaskov (MKD) T192 5. Joost de Heer (NLD) T189 T190 T191 Paul R˘aican 6. Emil Klemaniˇc (SVK) Kjell Widlert S´ebastienLuce V´aclavKotˇeˇsovec after Unto Hainonen 7. -

Bccf E-Mail Bulletin #74

BCCF E-MAIL BULLETIN #74 To subscribe, send me an e-mail ([email protected]) or sign up via the BCCF (www.chess.bc.ca) webpage; if you no longer wish to receive this Bulletin, just let me know. Stephen Wright [Back issues of the Bulletin are available on the above webpage.] WORLD YOUTH CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP The 2005 WYCC is currently underway in Belfort, France. This 11-round Swiss by age group (under 10, 12, 14, 16, and 18, in both boys and girls categories) has attracted 1122 players from around the world, including twenty-eight participants from Canada. Of these twenty-eight, eight are from B.C.: Fanhao Meng and Lucas Davies (U18B), Tiffany Tang (U16G), Noam Davies and Vlad Gaciu (U14B), Chelsea Ruiter (U12G), and Alexandra Botez and Erika Ruiter (U10G). Good luck to all! Results, currently for the first three rounds, are available through the offical sites, or www.chess.bc.ca or pages.infinit.net/archamse/WYCC2005.htm. The official website (www.belfort-echecs.com) was overwhelmed for a few days, but is currently up and running; an alternative is www.echecs.asso.fr/(0uiuf4binynjxpidzpz1f455)/Default.aspx, the website of the French Chess Federation. The organizers are providing games from the top twenty boards or so of each section, usually late on the same day as the round in question. So far four B.C. games are available, but unfortunately playing on the top twenty boards means meeting the toughest opposition, so the results have not been favourable for B.C.: Milman,L - Davies,L [B14] WYCC U18B Belfort (1.11), 19.07.2005 1.e4 c6 2.d4 -

Articles by the New York Times On

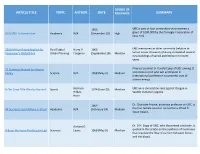

DEGREE OF ARTICLE TITLE TOPIC AUTHOR DATE RELEVANCE SUMMARY 1933 UBC is part of four universities that received a $200 000 To Universities Academia N/A (December 20) High grant of $200,000 by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. $200-Million Rebuilding Set for Real Estate/ Harry V. 1966 UBC mentioned as older university (relative to Vancouver's Waterfront Urban Planning Forgeron (September 18) Mention Simon Fraser University) having completed several new buildings of varied architecture in recent years. 21 Scientists Named for Atomic Physical scientist D. Harold Copp of UBC among 21 Parley Science N/A 1958 (May 3) Medium scientists named who will participate in international conference on peaceful uses of atomic energy. 8-Oar Crew Title Won by Harvard Sports Norman 1974 (June 23) Mention UBC wins consolation race against Oregon in Hildes- Seattle invitation regatta. Heim 1964 Dr. Charlotte Froese, associate professor at UBC, is 94 Scientists Get Millions in Grant Academia N/A (February 24) Medium the first female scientist named for a Alfred P. Sloan Award. Richard D. Dr. D.H. Copp of UBC, who discovered calcitonin, is A Bone Hormone Produced in Lab Sciences Lyons 1968 (May 9) Mention quoted in this article on the synthesis of hormones that regulate the flow of calcium between bones and the blood. A Curious Sugar Source Sciences N/A 1924 (June 26) High Professor John Davidson, botanist at UBC, carries out study showing that "Indians" had sugar before the arrival of white man. UBC alumnus (Bachelor’s Degree in History) Holger A Footnote: Kaiser's Plan to Richard H. -

Bccf E-Mail Bulletin #177

BCCF E-MAIL BULLETIN #177 Your editor welcomes any and all submissions - news of upcoming events, tournament reports, and anything else that might be of interest to B.C. players. Thanks to all who contributed to this issue. To subscribe, send me an e-mail ([email protected]) or sign up via the BCCF webpage (http://chess.bc.ca/); if you no longer wish to receive this Bulletin, just let me know. Stephen Wright [Back issues of the Bulletin are available on the above webpage.] HERE AND THERE Carl Cozier Kickoff (November 7) Jonah Lee tied for first with Silas Maclachlan in the grade 6-7 Section of this scholastic tournament in Bellingham, WA: http://www.whsca.org/report09-10/Cozier.html World Youth Chess Championships (November 11-23) This year the WYCC returns to its site of two years ago, Kemer-Antalya in Turkey. Twenty-one Canadians are participating in this year's edition, including four from B.C.: Dezheng Kong (U10), Jack Qian (U12), Alexandra Botez (U14G), and Karen Lam (U16G). Results and some live games should be available from the websites listed below. Official website: http://wycc2009.tsf.org.tr/ Canadian team blog: http://2009cyct.blogspot.com/ North America Youth Chess Championships Redux One of Janak Awatramani's gold-medal games has been annotated by Jonathan Berry in his Globe and Mail chess column: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/opinions/chess/article1346682/ BCBASE UPDATED BCBASE is a database of games, currently numbering 17,746, either played in British Columbia or by B.C. players elsewhere in the world. -

Chess Federation Piatigorsky Trio

PIATIGORSKY TRIO * (See p. 162) .:< UNITED STATES Volume XVIII Num ber 7/8 EDITOR: J. F. Reinhar dt CHESS FEDERATION PIATIGORSKY TRIO PRESIDENT Fred Cr amer Not since New Yo rk 1924 has there been an international cnes;s eHOt in the VICE PRESIDENT United States comparable to the recently·co ncluded Piatigorsky (up tf.lu.."1' ament in Major Edmund B. Edmondson, Jr. Los Angeles. This month·s CHESS LIFE cover proudly f eatur ~ ille ih:-ee people REGIONAL VICE·PRESIDENTS most responsible for the staging of thi'i great event : wodd·! eaowned cellb, Gregor NEW ENGLAND William C. Newberr) J ames Butl eSs Piatigorsky, his wife Jacqueline, and FIDE Vice·President Jerry Spann. Ell Bourdon EASTERN David Hoffmann Charles A. Keynr Allen Kauf mann Chess player s all over the world wi ll enjoy, for years to come. the ia..I:l~ played MID·ATLANTIC by eight of the leading gr:lndmasters- including Wcrld Champion PetroPio it this fine tournament. For a great chess tournament, unlike other 5por<'i.'l 2 E'n!I!;;, does SOUTHERN not fade with the passage of ti me. Every move that is played is r ecord€'C. ~ becomc3 GREAT LAKES Jack O'Keefe a part of the ever·growing chess heritage that all of us share. F. Wm. Bauer Dr. Howard Gaba NORTH CENTRAL Dr . Geo. Van Dyke Tiers Frank Skott Eva Aronaon The Piatlgorsky Cup is an important milestone in the den'lopment of .~rican SOUTHWESTERN J uan J . Reid chess. Just as we are growing on a l ~ ationa l scale (see President (r;;.m = r · ~ r'E9Ort on C. -

Bccf E-Mail Bulletin #73

BCCF E-MAIL BULLETIN #73 To subscribe, send me an e-mail ([email protected]) or sign up via the BCCF (www.chess.bc.ca) webpage; if you no longer wish to receive this Bulletin, just let me know. Stephen Wright [Back issues of the Bulletin are available on the above webpage.] VANCOUVER SEASONAL GRAND PRIX: SUMMER OPEN The last event of the Seasonal Grand Prix took place at the Vancouver Bridge Centre (we think) on the weekend of June 25-26. No other information is available other than the crosstable, so here it is: # Name Rtng 1 2 3 4 Tot 1 Andrey Kostin 1919 W11 W 8 W 2 D 5 3.5 2 Richard Ingram 2061 W 5 W 4 L 1 W 7 3.0 3 Ben Daswani 1947 W 7 D 0 L 4 W10 2.5 4 Louie Jiang 1879 W 0 L 2 W 3 D 6 2.5 5 Robert Hamm 1683 L 2 W 9 W12 D 1 2.5 6 Michael Yip 1999 D 0 D 0 D 0 D 4 2.0 7 Sterling Dietz unr. L 3 W12 W 8 L 2 2.0 8 Manuel Escandor 1815 W10 L 1 L 7 D 9 1.5 9 Vlad Gaciu 1784 D12 L 5 D10 D 8 1.5 10 Michael Wee 1321 L 8 W11 D 9 L 3 1.5 11 Thomas Witecki 1140 L 1 L10 W 0 D12 1.5 12 Alexandra Botez 1329 D 9 L 7 L 5 D11 1.0 More general information can be found at http://www.geocities.com/vanseasonal/ , including the Grand Prix standings after the first three events. -

Robert Byrne & Pal Benko Win 1966 United States Open Championship

Robert Byrne & Pal Benko Win 1966 United States Open Championship By Buz Eddy from September 1966 NORTHWEST CHESS LETTER 201! The third largest U.S. Open, and way for Robert Erkes, of Baltimore Md., as the eighth largest chess tournament ever con- he posted a 8.5-4.5 record a point and a half ducted in the United States was held last ahead of his nearest competition. month in Seattle. Micheal Murray of Missoula, Vince Gillis each posted a 7.5-5.5 The 1966 U.S.Open was won by two grand- record to share top class "C" masters, ROBFRT BI5NE, and PAL BENKO. The money. Murray took the trophy on USCF does not break first place ties, and tie breaking the two players are United States Open Co- The turn out of Champions. Byrne and Benko each scored 11 - 201 at this event must 2 in the thirteen round event. Byrne was be considered an overwhelming success, and undefeated, but was held to four draws in yet we might have done considerably better his games with Arthur Bisguier, Anthony Saidy had it not been for two uncontrolable oc- Durican Suttles, and Co-champion Benko. Benko curances. The airline strike apparently was upset in round four by Californian mas- held many eastern players home, and the fact ter Peter Cleehorn, and drew with Byrne and that the Paitogorisky Cup Tournament was Suttles. still in progress as our tournament began Duncan Suttles took a clear third place held nearly a dozen L.A. players away as in the tournament with a 10- 3 record, losing they were busy supporting that event. -

Pairs 4000 Tournament I Active/Blitz Tournament (A 2005 Elod Macskasy Memorial Fundraising Event)

Pairs 4000 Tournament I Active/Blitz Tournament (A 2005 Elod Macskasy Memorial Fundraising Event) March 20, 2004 Vancouver Bridge Center Are two heads better than one? Now’s your chance to find out by joining fellow chess enthusiasts on Saturday, March 20, 2004, for a challenging day of chess entertainment. Here’s the way it works. Grab a partner and play. But there are some rules: 1. The combined rating of each partnership may not exceed 4000. Two 2000 players could partner, a 2200 player could team up with anyone rated 1800 or lower, and so on. 2. The amount of time each partnership receives in each event is related to its combined rating. There are two events: a. Active: Teams receive between 15 minutes and half an hour. b. Blitz: Teams receive between two and a half minutes and six minutes. Combined rating Active Time Blitz Time 4000 15 minutes 2 min 30 sec 3950 16 minutes 2 min 45 sec 3900 17 minutes 3 minutes 3850 18 minutes 3 min 15 sec 3800 19 minutes 3 min 30 sec 3750 20 minutes 3 min 45 sec 3700 21 minutes 4 minutes 3650 22 minutes 4 min 15 sec 3600 23 minutes 4 min 30 sec 3550 24 minutes 4 min 45 sec 3500 25 minutes 5 minutes 3450 26 minutes 5 min 15 sec 3400 27 minutes 5 min 30 sec 3350 28 minutes 5 min 45 sec 3300 29 minutes 6 minutes 3250 30 minutes 6 minutes Round combined rating up to the nearest number divisible by 50 (3962 = 4000; 3643 = 3650, etc.) 3. -

Challenging Assorted Masters in a Continuous Simultaneous Exhibition

Challenge the Masters II Multi-Master Simul Tournament (A 2005 Elod Macskasy Memorial Fundraising Event) November 15, 2003 Vancouver Bridge Center Join fellow chess enthusiasts on Saturday, Nov 15, 2003, for a full day of entertainment by challenging assorted masters in a continuous simultaneous exhibition. Here’s your chance to play against GM Duncan Suttles, FM Oliver Schulte, FM Jack Yoos, FM Bruce Harper, Fanhao Meng, Luc Poitras and other masters and experts. Each master will play eight boards for 15 minutes, then rotate to the next eight boards, being replaced by another master, and so on. The number of masters playing at any particular time will depend on the number of participants in the exhibition. At different times, different masters will be playing. No consultation between the masters will be permitted – they will have to figure out what their predecessors were doing. Participants may begin a new game whenever they like and may play as many games as time permits. No new games may be started after 3:00 pm. Be there early or be there late – but be sure to be there! Pre-register to reserve a board, so you can sit with your friends. Date November 15, 2003 (Saturday) Location Vancouver Bridge Center 2776 East Broadway (Broadway and Kaslo) Vancouver, British Columbia Information Contact: Richard Reid 16996 104A Ave. Surrey, B.C. V4N 3L9 Tel: (604) 589-4214 email: [email protected] Registration Nov 15, 9:00-9:30 am. Deadline for pre-registration, Nov 13, 2003 Format Continuous play simultaneous. Time Control 60 minutes for participants, 90 minutes for the masters. -

Bccf E-Mail Bulletin #56

BCCF E-MAIL BULLETIN #56 To subscribe, send me an e-mail ([email protected]) or sign up via the BCCF (www.chess.bc.ca); if you no longer wish to receive this Bulletin, just let me know. Stephen Wright [Back issues of the Bulletin are available on the above webpages.] DAN SCOONES ANNOTATES Dan Scoones has kindly submitted annotations to one of his games from the recent Victoria Labour Day tournament - thanks Dan! Lister,C (1968) - Scoones,D (2291) [B06] Labour Day Open Victoria (2), 04.09.2004 [Scoones, Dan] 1.e4 g6 2.d4 d6 3.Nc3 c6 4.Be3 Bg7 5.Bc4!? A bit risky in view of Black's possibilities of ...b5 or ...d5. 5...Nf6 6.f3 d5 7.Bd3 [Sharper is 7.Bb3 A) If this does not appeal, Black has the more solid 7...0–0 8.Nge2 dxe4 9.fxe4 Ng4 10.Bg1 e5 (not 10...c5 11.dxc5 Qa5 12.Qd3 Nc6 13.h3 Rd8 14.Qb5 and White is better) 11.d5 Qa5 12.Qd3 Rd8 13.Rd1 Na6; B) 7...dxe4 8.fxe4 Ng4 9.Qf3 0–0 10.0–0–0 Nxe3 11.Qxe3 b5 12.Nf3 a5 13.d5 a4 14.dxc6 with a complicated struggle.] 7...dxe4 8.Bxe4 [Of course White cannot consider 8.fxe4? Ng4 and d4 falls.] 8...Nbd7 [8...Nd5 deserved attention, for example: 9.Bf2 (not 9.Nxd5 cxd5 10.Bd3 Qb6 11.Rb1 Nc6 12.c3 Ne5! 13.Be2 Bf5 14.Rc1 0–0 15.Bg5 f6 16.dxe5 fxg5 17.Qxd5+ e6 18.Qb3 Qe3 with a big advantage for Black) 9...Nxc3 10.bxc3 0–0 11.Ne2 e5 , and despite his lag in development Black is somewhat better because of White's devalued pawn structure.] 9.Nge2 Nb6 10.0–0 0–0 11.Bd3 Nfd5 12.Nxd5 Nxd5 13.Bc1 e5 [If 13...Qb6 14.Kh1 Bxd4 15.Nxd4 Qxd4 16.Qe1 and White has compensation for the pawn. -

Historical WASHINGTON CHESS LETTER Recaps

Historical WASHINGTON CHESS LETTER recaps (in the pages of Washington Chess Letter and Northwest Chess) by Russell Miller 1949-1989 at ten-year intervals July 1949 (WCL) The cover of WASHINGTON CHESS LETTER (WCL) for July 1949 says “International Match Issue.” There are 11 pages of material in this issue by Editor Jack L. Finnigan of Gig Harbor and published by Peter Husby of Everett. In news, Gerald Schain topped the U of W final quarter tournament with James Amidon second and Ham Martin third. 20 players took part in the A section and 12 in the B. Norm Newblom won the B Section. In a letter to the Editor, Larry Hagen of Corvallis Oregon thinks the Portland CC should play a match against Puget Sound League champion team. Tacoma CC and the editor agree. The International Match of Washington vs. BC was set for July 3, 1949. There were to be matches in other area of the USA and Canada on the same day. The match with BC was to be played in Seattle. A history article by Richard Allen appeared in this issue. For more info on all the matches over the years check out the website http://www3.telus.net/public/swright2/bcwam.html. 23 players took part in the Puget Sound Open held in Everett. Scoring 5-1 were U of W student Jim Amidon and Richard Allen of Seattle. Sonnenbern-Berger tie-breaking points gave the title to Amidon. Amidon won $15 and Allen $5. Guess they did not combine and split prize money in those days. -

Chess Olympiad at Varna with FISCHER U

MY FIRST GAME XVth Chess Olympiad at Varna WITH FISCHER U. S. S. R. Is Victar by World Champion Varna, the Rulgarian resort town situated on the west shore of the Black Sea, Mikhail Bohinnik was the host to thirty· ni ne participating countries in the !-'ifteenth Chess Olympics from September 15 to October 10. (A Cltes"s Life Exclusive) Each country entered a four-board team and the 39 teams were divided Into GRUNFELO DEFENSE four preliminary groups, each group playing a round·robin. After the completion of the preliminary tournament, the three lop-scoring learns of each group were placed White: Botv jnnik Black: Fi5cher in "Section A" of the Finals; the next three in "Section B" and the remainder in 1. P·Q&4 P-KN3 "Section C. " Groups w('re determined at a technical conference of team captains 2. P·Q4 H·KB3 and lots were drawn to determine competitive numbers of the teams. Play was 3. N·QB3 P·Q4 started at 4 P.M., local time, Sept. 16 by the referee, International Grandmaster Salo Flohr of the U.S.S.R. f'il;chcr very rarely plays the Grunfeld Defense. The four top seeded teams, U.S.A., Argenti na, U.S.S.R. and Yugoslavia, were placed in different groups and each lived up to expectations by taking first place 4. N·B3 B·N2 in its group. And, in fact, they were the fou r top finalists. 5, Q.N3 ..... ... nagosin's Systcm-onc of the strongest The l:.S.S.R.