Trends and Developments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Seasonal Search for the Phantom of Brewing

A seasonal search for the phantom of brewing The Belgian man-in-the Street (or rue) is probably knowledgeable about beer than his counterpart in other countries. Despite that, he is still inclined to take for granted the marvelous beer selection in his own land. The integrity of several Belgian beer styles is in danger and some could vanish. Perhaps the most endangered is the Saison. This style is not widely known outside its region of production of Hainaut, in the French speaking half of the country. It was my interest in this style that led me to make my first visit to the Dupont brewery. This is in the hamlet of Tourpes, in the municipality of Leuze, in western Hainaut. The making of Saisons was regarded as a distinctly Belgian technique by brewing scientists in the late 1800s and early 1900s, though they were produced to meet a situation common to all brewing nations. They were originally made during the winter by farmer-brewers, then laid down for consumption during the summer. The beer had to be sturdy enough to last for some months, but not too strong to be a summer and harvest quencher. Rocky Saisons were regarded in Belgium as beers of medium gravity (today, anything from 1048 to 1080). The method, probably arrived at empirically, was to use high mashing temperatures, producing a substantial degree of unfermentable sugars, and to have a period of warm conditioning, usually in metal tanks. In the Belgian tradition, Saisons are top-fermenting and bottle-conditioned. These beers are often presented in Champagne-style bottles, and were before the more widespread revival of this presentation. -

Hanoi a Beer Drinker'

Hanoi a beer drinker's haven (11/10/2012) Hanoi has been named one of the cheapest and best places to drink fresh beer in Asia by travel guides and journalists, thanks to its lively drinking culture. Many tourists look forward to the chance to join local Hanoians and enjoy the city's famous Bia Hoi (fresh beer) - a light-bodied pilsner without preservatives that is brewed and delivered daily to drinking places throughout the capital. Hanoi has become a magnet for tourists who enjoy drinking beer, which is readily available at local pavement shops as well as in luxurious bars. There are thousands of corner bars with tiny plastic stools set out on the sidewalk and small low tables laden with glasses of beer. Visitors should taste Vietnamese beer and learn how local people drink. "Mot, hai, bazo!! (One, two, three go!!) and "Tram phan tram! ("100 percent" or "bottoms up") are common chants that accompany a drinking session in these local establishments. "Bia Hoi is one of things you should not miss when you come to Hanoi, says Thomas, a foreign tourist who chooses Hanois old quarter as his favourite place to imbibe a cool brew. He says he likes Hanoi beer because it is very cheap and delicious. Another thing that amazes visitors is that the beer bars are mostly on the sidewalk where drinkers sometimes have to raise their voices over the din of motorbike traffic or breathe in the clouds of diesel exhaust belched over the plastic tables by a passing bus. "Sitting on the pavement, listening to the mixed sounds, drinking beer and just looking at what's happening around me has become my habit during my time in Hanoi, Thomas elaborates. -

Imported Beer Xingu

New Release Cabernet Sauvingnon • Moscato • White Zinfandel • Merlot Pinot Noir • Chardonnay • Riesling • Pinot Grigio Award Winning Enjoy Our Family’s Award Winning Tequilas Made from 100% Agave in the Highlands of Jalisco. www. 3amigostequila.com Please Drink Responsibly Amigos Visit AnchorBrewing.com for new releases! ANCB_AD_Hensley.indd 1 P i z z a P o r t 9/19/17 10:46 AM Brewing Company Carlsbad, CA | Est. 1987 Good Beer Brings Good Cheer Every Family has a Story. Welcome to Ours! 515144 515157 515147 515141 515142 515153 515150 515152 515140 Chateau Diana Winery: Family Owned and Operated. PRESCOT T BREWING COMPANY’S ORIGINAL PUB BREWHOUSE Established 1994 10 Hectolitre, three fermenters then, five now, 1500 barrels current annual capacity. PRESCOT T BREWING COMPANY’S PRODUCTION PLANT Established 2011 30 barrel brewhouse, 30, 60, and 90 barrel fermenters, 6,800 barrel annual capacity with room to grow. 130 W. Gurley Street, Prescott, AZ | 928.771.2795 | www.prescottbrewingcompany.com The Orange Drink America Loves! 100% Vitamin C • 60 calories per 8 oz. Available in 8 flavors • 16 oz. bottle © 2017 Sunny Delight Beverage Co. 8.375” x 5.44” with a .25 in. bleed Small Batch Big Fun World Class Kick Ass Rock & Roll Every Margarita in the ballpark Tequila! is poured with our Silver Tequila! Premium craft tequila ~ made in Mexico locally owned by roger clyne & The Peacemakers Jeremy Kosmicki Head Brewmaster Jason Heystek Lead Guitar/Barrel Maestro WE ARE FLAGSTAFF PROUDLY INDEPENDENT TABLE OF CONTENTS DOMESTIC BEER MODERN TIMES BEER .................................... 8 DAY OF THE DEAD ....................................... 12 10 BARREL BREWERY .................................... -

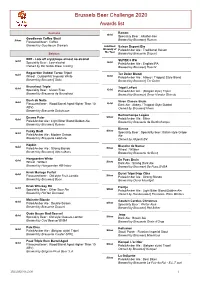

Brussels Beer Challenge 2020 Awards List

Brussels Beer Challenge 2020 Awards list Australia Ramon Gold Speciality Beer : Alcohol-free Goodieson Coffee Stout Silver Brewed by Brouwerij Roman Flavoured beer : Coffee Brewed by Goodieson Brewery Gold Best Saison Dupont Bio Brewery of Pale&Amber Ale : Traditional Saison the Year Belgium Brewed by Brasserie Dupont BIIR - Lots off cry(o)hops almost no alcohol SUPER 8 IPA Gold Gold Speciality Beer : Low-alcohol Pale&Amber Ale : English IPA Owned by Biir Noble Brew Trading Brewed by Brouwerij Haacht Bogaerden Dubbel Tarwe Tripel Ter Dolen Blond Gold Gold Wheat : DubbelWit/ Imperial White Pale&Amber Ale : Abbey / Trappist Style Blond Brewed by Brouwerij Sako Brewed by Brouwerij Ter Dolen Brunehaut Triple Tripel LeFort Gold Gold Speciality Beer : Gluten Free Pale&Amber Ale : (Belgian style) Tripel Brewed by Brasserie de Brunehaut Brewed by Brouwerij Omer Vander Ghinste Bush de Nuits Viven Classic Bruin Gold Gold Flavoured beer : Wood/Barrel Aged Higher Than 10 Dark Ale : Abbey / Trappist Style Dubbel ABV) Owned by Brouwerij Viven Brewed by Brasserie Dubuisson Bertinchamps Légère Ename Pater Silver Gold Pale&Amber Ale : Bitter Pale&Amber Ale : Light Bitter Blond/Golden Ale Brewed by Brasserie de Bertinchamps Brewed by Brouwerij Roman Bienne Funky Brett Silver Gold Speciality Beer : Speciality beer: Italian style Grape Pale&Amber Ale : Modern Saison Ale Brewed by Brasserie Lefebvre Owned by Aligenti BV Hapkin Blanche de Namur Gold Silver Pale&Amber Ale : Strong Blonde Wheat : Witbier Brewed by Brouwerij Alken-Maes Brewed by Brasserie du -

Belgian Beer Experiences in Flanders & Brussels

Belgian Beer Experiences IN FLANDERS & BRUSSELS 1 2 INTRODUCTION The combination of a beer tradition stretching back over Interest for Belgian beer and that ‘beer experience’ is high- centuries and the passion displayed by today’s brewers in ly topical, with Tourism VISITFLANDERS regularly receiving their search for the perfect beer have made Belgium the questions and inquiries regarding beer and how it can be home of exceptional beers, unique in character and pro- best experienced. Not wanting to leave these unanswered, duced on the basis of an innovative knowledge of brew- we have compiled a regularly updated ‘trade’ brochure full ing. It therefore comes as no surprise that Belgian brew- of information for tour organisers. We plan to provide fur- ers regularly sweep the board at major international beer ther information in the form of more in-depth texts on competitions. certain subjects. 3 4 In this brochure you will find information on the following subjects: 6 A brief history of Belgian beer ............................. 6 Presentations of Belgian Beers............................. 8 What makes Belgian beers so unique? ................12 Beer and Flanders as a destination ....................14 List of breweries in Flanders and Brussels offering guided tours for groups .......................18 8 12 List of beer museums in Flanders and Brussels offering guided tours .......................................... 36 Pubs ..................................................................... 43 Restaurants .........................................................47 Guided tours ........................................................51 List of the main beer events in Flanders and Brussels ......................................... 58 Facts & Figures .................................................... 62 18 We hope that this brochure helps you in putting together your tours. Anything missing? Any comments? 36 43 Contact your Trade Manager, contact details on back cover. -

Kirin Report 2016

KIRIN REPORT 2016 REPORT KIRIN Kirin Holdings Company, Limited Kirin Holdings Company, KIRIN REPORT 2016 READY FOR A LEAP Toward Sustainable Growth through KIRIN’s CSV Kirin Holdings Company, Limited CONTENTS COVER STORY OUR VISION & STRENGTH 2 What is Kirin? OUR LEADERSHIP 4 This section introduces the Kirin Group’s OUR NEW DEVELOPMENTS 6 strengths, the fruits of the Group’s value creation efforts, and the essence of the Group’s results OUR ACHIEVEMENTS and CHALLENGES to OVERCOME 8 and issues in an easy-to-understand manner. Our Value Creation Process 10 Financial and Non-Financial Highlights 12 P. 2 SECTION 1 To Our Stakeholders 14 Kirin’s Philosophy and TOPICS: Initiatives for Creating Value in the Future 24 Long-Term Management Vision and Strategies Medium-Term Business Plan 26 This section explains the Kirin Group’s operating environment and the Group’s visions and strate- CSV Commitment 28 gies for sustained growth in that environment. CFO’s Message 32 Overview of the Kirin Group’s Business 34 P. 14 SECTION 2 Advantages of the Foundation as Demonstrated by Examples of Value Creation Kirin’s Foundation Revitalizing the Beer Market 47 Todofuken no Ichiban Shibori 36 for Value Creation A Better Green Tea This section explains Kirin’s three foundations, Renewing Nama-cha to Restore Its Popularity 38 which represent Group assets, and provides Next Step to Capture Overseas Market Growth examples of those foundations. Myanmar Brewery Limited 40 Marketing 42 Research & Development 44 P. 36 Supply Chain 46 SECTION 3 Participation in the United Nations Global Compact 48 Kirin’s ESG ESG Initiatives 49 This section introduces ESG activities, Human Resources including the corporate governance that —Valuable Resource Supporting Sustained Growth 50 supports value creation. -

An Exquisite French Taste for an International Gourmet Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AN EXQUISITE FRENCH TASTE FOR AN INTERNATIONAL GOURMET FESTIVAL SELANGOR, 26 August 2013 – Carlsberg Malaysia is proud to announce its involvement as the official beer sponsor, for the 3rd consecutive year, in the 2013 Malaysian International Gourmet Festival (MIGF). The spectacular month long food fair will see Carlsberg Malaysia’s No.1 French Premium beer, Kronenbourg 1664 participate in an assortment of culinary activities complementing the annual culinary fiesta. Known as the Champagne of beers, Kronenbourg 1664 lager and Kronenbourg 1664 Blanc is the beer of choice that offers an exquisite drinking experience to discerning drinkers who indulge in food and beer pairing. Kronenbourg 1664 is a smooth rounded beer and has a sparkling mouth-feel with a tinge of bitterness while Kronenbourg 1664 Blanc presents a lighter sweetness combining the flavours of coriander and clove, both of which brings out the best textures in an array of foods. Further enhancing the experience of the gastronomic affair, there will be specially designed menus that bring out the best in both food and drink in few of the participating outlets. Each pairing of flavours and style tantalises the palate with a spectacular epicurean delight that is guaranteed to entice the taste buds of food connoisseurs around town. “Our partnership with MIGF and has enabled us to showcase our portfolio of premium beers and innovation within the food and beer pairing activities here in Malaysia. We are very excited to present Kronenbourg 1664, the No.1 French beer around the world as the preferred alcohol beverage of all penchants and occasions,” commented Juliet Yap, Marketing Director of Carlsberg Malaysia. -

Strategic and Financial Valuation of Carlsberg A/S

Strategic and Financial Valuation of Carlsberg A/S Master Thesis – Finance and Strategic Management 30th of September 2011 Cand. merc. FSM Department of Finance Copenhagen Business School Author: Andri Stefánsson Supervisor: Carsten Kyhnauv Strategic and Financial Valuation of Carlsberg A/S Executive summary The main objective of this thesis was to determine the theoretical fair value of one Carlsberg A/S share on the 1st of March 2011. Carlsberg A/S is the world´s 4th largest brewery measured in sales volume and has acquired this position both through organic growth as well as acquisitions of its competitors as a part of the consolidation phase that the brewing industry has undergone in the past 10 years. In order to obtain the necessary understanding of the company´s business model, a strategic analysis was carried out both on an external as well as on an internal level. The strategic analysis showed that Carlsberg has a very strong product portfolio and one of its main strengths was innovation in regards to new products targeting new market segments. Being the 4th largest brewery in the world creates great economies of scale which are of importance. The strategic analysis also showed that the political and economical situation in Russia is of most threat to Carlsberg. The strategic analysis was followed by a financial analysis which showed that all key financial drivers rose upon till 2008 when the recent economic crisis hit and Carlsberg at the same time acquired Scottish & Newcastle. From 2009 the key financial drivers showed improvements both due to Carlsberg being able to make use of the synergies created as a part of the acquisition along with an increase in revenue and lower borrowing costs. -

Davide Scabin Gin Hendrick's Anteprime Joaquin Conterno Fantino Ferrari

gourmet Davide Scabin Food e arte Gin Hendrick’s Eccellenza e follia Anteprime Bardolino e Montepulciano Joaquin La sfida impossibile Conterno Fantino Tra tradizione e modernità Ferrari Una degustazione unica colophone editoriale gourmet Vby Brunio Ptetroanilli da gourmet Secondo appuntamento, secondo viaggio, stesse emozioni alla ricerca del gusto, dell’eccellenza, dell’esclusività. Joaquin e Gin Hendrick’s, racconti che parlano di sfide, preziosità, valori e anche di un pizzico di follia. direttore responsabile Matteo Tornielli Il nostro amato mondo gourmet è popolato da quotidiane esperienze alla [email protected] direttore editoriale Bruno Petronilli ricerca della perfezione, della conoscenza, della felicità. [email protected] creative director Federico Menetto Ecco perché Davide Scabin e Luigi Taglienti sono esempi di come [email protected] attraverso l’arte culinaria si possa raccontare l’emotività del piacere. segreteria [email protected] abbonamenti www.liveinmagazine.it Come in una degustazione “infinita” delle nostre amate bollicine Ferrari, hanno collaborato Luca Bonacini, Boz, Roberto Carnevali, Alberto Cauzzi, Tommaso Cornelli, Laura Di Cosimo, Alessandro Franceschini, o come nelle anteprime, un occhio al futuro assaporando il presente. Daniele Gaudioso, Federico Malgarini, Emanuele Mazza, Alessandro Pellegri, Alessandra Piubello, Paolo Repetto, Giovanna Repossi, Irene Santoro, Luca Turner. Ma soprattutto un grazie sincero a tutti coloro che hanno contribuito a editore S.r.l. Viale Navigazione Interna 51/A 35129 Padova (Italy) questo numero, amici da una vita, professionisti di quelle passioni che ci spingono tel. +39 0498172337 - [email protected] pubblicità [email protected] sempre più là, tra sogno e realtà. stampa Chinchio Industria Grafica Spa Via Pacinotti, 10/12 - 35030 Rubano (Pd) In collaborazione con I.T.I. -

Download Presentation

Irlanda Italiana Association Food & Drink Valle D’Aosta Area: 3,263 km² Population: 123,978 DensitC: 38/km² Capital: Aosta Main Cities: Aosta, ArGad, CourHayeur, La Thuile Food & Drink Fontina: cheese made Mom cow's milk that originates Mom the Valley, it is found in dishes such as a <<soup alla valpellinentze>> Carbonada: salt-cured beef cooked with onions and red wine ser[ed with polenta Black bread Gamay: the local light red wine, it gWows on the terWaced vineyards visible along the steep rock walls of the valley Piemonte Area: 25,399 km² Population: 4.3 million DensitC: 171/km² Capital: Turin (Torino) Main Cities: Alessandria, Asti , Biella, Cuneo, Novara, Torino, Verbano-Cusio-Ossola, Vercelli Food • Bollito Misto: mix of beef and pork meat boiled with vegetables and eaten with a varietC of sauces & Frio Misto: mixfre of Mied meats and vegetables Baga Cauda: hot garlic and anchovies creamy sauce eaten with raw vegetables Panissa Vercellese: tCical dish Mom Vercelli made with rice, beans and sausages Drink Barolo and Barbaresco are the most famous wines Mom Piemonte Asti is a sparkling wine Mom the Moscato gWape There are also beers like Menabrea and aromated wines Lombardia Area: 23,861 km² Population: 9.4 million DensitC: 401/km² Capital: Milan (Milano) Main Cities: Bergamo, Brescia, Como Cremona, Lecco, Lodi, Milano, Mantova Monza e della Brianza, Pavia, Sondrio, Varese Food Polenta (Asino e Polenta, Polenta e Osei, Polenta e Gorgonzola): dish made om boiled cormeal Pizzoccheri: shore tagliatelle made out of buckwheat flour and wheat, laced with buder, gWeen vegetables, garlic, sage, potatoes and onions, all topped with Casera cheese Risodo alla Milanese: The best known version of risodo, flavoured with salon and tCically ser[ed with many tCical Milanese main courses like Ossobuco alla Milanese, a dish of braised veal shanks Drink Oltepò Pavese: a remarkable wine zone with 14 different tCes of wine (Pinot Nero, Barbera, Croatina, Uva Rara, Vespolina, etc…). -

Further Study on the Affordability of Alcoholic

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public INFRASTRUCTURE AND service of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND TERRORISM AND Browse Reports & Bookstore HOMELAND SECURITY Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discussions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instru- ments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research professionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports un- dergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Travel in Vietnam

citypassguide.com BY LOCALS, FOR LOCALS - YOUR MONTHLY HCMC GAZETTE Volume 8 | June 2016 TRAVEL IN VIETNAM / “A journey is best meASURED IN FRIENDS, RATHER THAn miles.” – TIM CAHILL / MY THO PHONG NHA SAPA THE GATE TO THE MEKONG LARGEST CAVE IN THE WORLD THE TOWN IN THE CLOUDS 6 19 22 What’s Happening • Travel • Destinations Emmotional Baggage • Events PUBLISHED BY #iAMHCMC NEWS NEWS #iAMHCMC The following information Korea for the first time. Customs figures showed regions without clean water, and 1.1 million Foreign investment #iAMHCMC is provided by that 7,800 cars worth around US$140 million in need of food support. Officials from the By Locals, For Locals made in Thailand were sold to Vietnam in the agriculture ministry and United Nations have It has been a good few months for foreign investors first three months, up 64.5 percent from a year estimated that more than 60,000 women and in Vietnam. The government has decided to open What’s Happening ago. The market growth was thanks mostly to children in 18 hardest-hit provinces are facing up the fuel retail market for outsiders, with Japan’s a new free trade agreement that has cut import malnutrition. Around 1.75 million people from Idemitsu Kosan and Kuwait Petroleum on track by Le Trung Dung tariffs among the 10 ASEAN member states from farming families have suffered heavy losses to jointly launch the first fully foreign-owned oil CEO Patrick Gaveau 50 percent to 40 percent this year. The tax rate as drought damage to agriculture activities is business in the country.