Carbon Footprint in the Annual Statements of Polish Mass Passenger Transportation Carriers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 34596 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION REPORT (TF-29121 FSLT-70540) ON A LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF EUR 110.0 MILLION (US$ 101.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT TO POLSKIE KOLEJE PANSTWOWE S.A. (POLISH STATE RAILWAYS S.A.) WITH THE GUARANTEE OF THE REPUBLIC OF POLAND FOR A RAILWAY RESTRUCTURING PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 13, 2006 Infrastructure Department Poland and Baltic States Country Unit Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective At Completion, December 30, 2005) Currency Unit = Polish Zloty PLN 1 = US$ 0.3099 US$ 1 = PLN 3.2265 US$ 1 = Euro 0.8391 (Exchange Rates Effective at Appraisal, January 31, 2001) PLN 1 = US$ 0.2418 US$ 1 = PLN 4.1350 US$ 1 = Euro 1.0887 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EIB European Investment Bank EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return FIRR Financial Internal Rate of Return FMS Financial Management System GoP Government of Poland IAS International Accounting Standards IFAC International Federation of Accountants ISPA Instrument for Structural Policies for Pre-accession KBI Capital Investment and Privatization Office KM Warsaw Regional Railways ('Koleje Mazowiekie') KAAZ Agency for Retraining and Reemployment ('Kolejowa Agencja Aktywizacji Zawodowej') LHS Linia Hutniczo-Siarkowa (Broad-gauge Railway between Ukraine and Silesia) LRS Labor Redeployment Services MoI Ministry of Infrastructure MLSP Ministry of Labor and Social Policy MTME Ministry of Transport and Maritime Economy NLO National Labor Office PAD Project Appraisal Document PLK S.A. Polish Railway Infrastructure Joint Stock Company ('Polskie Linie Kolejowe Spolka Akcyjna') PKP Polish State Railways ('Polskie Koleje Panstwowe') PKP S.A. -

Construction of a New Rail Link from Warsaw Służewiec to Chopin Airport and Modernisation of the Railway Line No

Ex post evaluation of major projects supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Cohesion Fund between 2000 and 2013 Construction of a new rail link from Warsaw Służewiec to Chopin Airport and modernisation of the railway line no. 8 between Warsaw Zachodnia (West) and Warsaw Okęcie station Poland EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Directorate Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Unit Evaluation and European Semester Contact: Jan Marek Ziółkowski E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Ex post evaluation of major projects supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Cohesion Fund between 2000 and 2013 Construction of a new rail link from Warsaw Służewiec to Chopin Airport and modernisation of the railway line no. 8 between Warsaw Zachodnia (West) and Warsaw Okęcie station Poland Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy 2020 EN Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). Manuscript completed in 2018 The European Commission is not liable for any consequence stemming from the reuse of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 ISBN 978-92-76-17419-6 doi: 10.2776/631494 © European Union, 2020 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. -

Regulamin Przewozu Osób, Rzeczy I Zwierząt Przez Spółkę „PKP Intercity” (RPO-IC)

Tekst ujednolicony obowiązuje od dnia 4 czerwca 2020 r. „PKP Intercity” Spółka Akcyjna R E G U L A M I N PRZEWOZU OSÓB, RZECZY I ZWIERZĄT przez Spółkę „PKP Intercity” (RPO-IC) Obowiązuje od dnia 16 listopada 2014 r. Regulamin przewozu osób, rzeczy i zwierząt przez Spółkę „PKP Intercity” (RPO-IC) Z chwilą wejścia w życie niniejszych przepisów tracą moc przepisy Regulaminu przewozu osób, rzeczy i zwierząt przez Spółkę „PKP Intercity” (RPO-IC) obowiązującego od dnia 19 marca 2013 r. ZMIANY Podpis osoby Podstawa wprowadzenia zmiany Numer Zmiana wnoszącej zmianę zmiany Uchwała Zarządu PKP Intercity S.A. obowiązuje od dnia Nr Data 1 932/2014 01.12.2014 r. 03.12.2014 r. 2 987/2014 11.12.2014 r. 14.12.2014 r. 3 227/2015 24.03.2015 r. 27.03.2015 r. 4 293/2015 02.04.2015 r. 09.04.2015 r. 5 387/2015 28.04.2015 r. 05.05.2015 r. 6 528/2015 17.06.2015 r. 21.06.2015 r. 7 572/2015 30.06.2015 r. 07.07.2015 r. 8 639/2015 28.07.2015 r. 30.07.2015 r. 9 718/2015 03.09.2015 r. 09.09.2015 r. 10 769/2015 18.09.2015 r. 22.09.2015 r. 11 869/2015 28.10.2015 r. 14.12.2015 r. 12 1011/2015 08.12.2015 r. 13.12.2015 r. 13 1069/2015 22.12.2015 r. 28.12.2015 r. 14 59/2016 04.02.2016 r. 04.02.2016 r. 15 161/2016 15.03.2016 r. -

The New Warszawa Zachodnia Station Opens Tomorrow

8 December 2015 Press Release The new Warszawa Zachodnia station opens tomorrow The new Warszawa Zachodnia (Warsaw West) railway station is ready for passengers' use just one year after its construction process begun. The building, which has an area of approx. 1,300 sq m, is located in the immediate vicinity of Aleje Jerozolimskie street in Warsaw, enabling residents from Ochota, Włochy and Mokotów districts to quickly and easily reach the station. The landmark new station’s striking design including a distinctive glass dome is the result of an efficient collaboration partnership between PKP S.A., Xcity Investment, and HB Reavis, an international developer group. As of tomorrow, people travelling from the Warszawa Zachodnia railway station will be able to access this brand new building, situated at Aleje Jerozolimskie street, closer to the tracks where local connections are available. The scheme will expand on the previous facility at Tunelowa street, which will continue to serve passengers. Due to its location, the new railway station will be more easily accessible by public means of transportation. 'This is our first investment undertaken in collaboration with PKP S.A. and we hope that it is not the last as the Warszawa Zachodnia station is great success. Within less than 12 months since construction works began, the building is now ready for use. Without a doubt, passengers will appreciate its striking design, impressive glass dome and surroundings, which already look attractive but will make even more of an impact once the adjacent office buildings are completed,' said Stanislav Frnka, CEO of HB Reavis Poland. -

Office of Rail Transport

Office of Rail Transport https://utk.gov.pl/en/new/16566,Open-access-to-railway-infrastructure-granted-to-4-carriers.html 2021-09-24, 13:42 Open access to railway infrastructure granted to 4 carriers 04.01.2021 In November and December 2020 the President of the Office of Rail Transport issued 11 administrative decisions granting 4 railway carriers open access to railway infrastructure. The legal basis for most of the decisions was Regulation 869/2014, which expired on December 12, 2020. The President of UTK issued decisions granting open access to four railway carriers: Polregio sp. z o.o. – 8 decisions, Koleje Mazowieckie – KM sp. z o.o. – 1 decision, Koleje Dolnośląskie S.A. – 1 decision. RegioJet a.s. – 1 decision. Non-confidential versions of these decisions were published in the Official Journal of the President of the Office of Rail Transport. - I am glad that I was able to issue further decisions granting open access. I trust that these decisions will contribute to increasing competitiveness. The passengers will benefit from additional connections, both all-year-round and seasonal, which complement the basic transport offer under public service contracts – comments Ignacy Góra, the President of the Office of Rail Transport. The legal basis for 10 administrative decisions was Regulation 869/2014 which expired on December 12, 2020. It means that the legal basis for pending and future open access proceedings will be Regulation 2018/1795. One of the most important changes in Regulation 2018/1795 is that the applicant is required to notify the infrastructure manager and the President of Office of Rail Transport (i.e. -

Managing Change in the Digital Age EDITOR-IN-CHIEF GRAPHIC DESIGNER, DTP Paweł Kubisiak Alicja Gliwa

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW POLSKA PRESENTS PKP Energetyka – a case study Managing change in the digital age EDITOR-IN-CHIEF GRAPHIC DESIGNER, DTP Paweł Kubisiak Alicja Gliwa CONTENT EDITOR PRODUCTION MANAGER Katarzyna Koper Marcin Opoński EDITORIAL ASSISTANT PROOFREADING Urszula Gabryelska Andrzej Retkiewicz AUTHORS MEDIA & MARKETING Tomasz Besztak SOLUTIONS DIRECTOR Ryszard Bryła Ewa Szczesik-Czerwińska Friederike Fabritius Phone no. 664 933 232 Paweł Górecki Beata Górniak ENGLISH VERSION Anna Hyży Marek Kleszczewski TRANSLATOR Katarzyna Koper Łukasz Łyp Stanisław Kubacki Paweł Kubisiak PROOFREADER Régis Lemmens Sue Sheikh Paweł Majka Ian Spriggs Hubert Malinowski Marek Mazierski Agnieszka Nosal Piotr Obrycki Robert Ryszkowski Marek Szumlewicz Filip Szumowski Mateusz Żurawik All rights reserved. This content cannot be copied, distributed or archived in any physical or digital form without the publisher’s consent. Quoting parts of articles or their reviews in any printed or digital form without the consent of the publisher (ICAN Spółka z ograniczoną odpowiedzialnością Sp.k.) is a copyright violation. ICAN Institute PKP Energetyka al. Niepodległości 18 ul. Hoża 63/67 02-653 Warszawa 00-681 Warszawa e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] www.ican.pl www.pkpenergetyka.pl Managing change in the digital age 2 Laying the ground for change 34 Next station: Digitization The process of change is a huge challenge for From support process automation to the AI support both leaders and employees of the transformed for railroad grid network and distribution network organisation. That is why the board implemented monitoring, digitisation converts data dispersed its programme of change using existing staff as far throughout a company into an operationally and as possible, only bringing in new staff in areas commercially meaningful information stream. -

A Student's Guide in Poland

This guidebook was prepared thanks to the collaboration of the Students’ Parliament of the Republic of Poland (PSRP), the Foundation for the Development of the Education System (FRSE) and the Erasmus Students Network Poland (ESN Poland). First edition author: Maciej Rewucki Contributors: Joanna Maruszczak Justyna Zalesko Pola Plaskota Wojciech Skrodzki Paulina Wyrwas Text editor: Leila Chenoir Layout: ccpg.com.pl Photos: Students’ Parliament of the Republic of Poland (PSRP) Erasmus Students Network Poland (ESN Poland) Foundation for the Development of the Education System (FRSE) Adam Mickiewicz University Students’ Union Bartek Burba Monika Chrustek Martyna Kamzol Łukasz Majchrzak Igor Matwijcio Patrycja Nowak Magdalena Pietrzak Bartek Szajrych Joanna Tomczak Adobe Stock First edition: September 2020 CONTENTS Preface by PSRP, ESN and FRSE PAGE 1 Welcome to Poland PAGE 2 Basic information about Poland PAGE 3 Where to find support during your first days in Poland? PAGE 4 PSRP and ESN PAGE 4 Higher education in Poland PAGE 10 Transportation in Poland PAGE 12 Other discounts and offers for students PAGE 14 Weather PAGE 15 Healthcare PAGE 16 Students with disabilities PAGE 17 Student unions in Poland PAGE 18 Bank account PAGE 19 Where to find accommodation? Tips and online sources PAGE 20 Mobile phones and Internet PAGE 22 Important contacts PAGE 23 Student life in Poland PAGE 25 Jobs for foreigners in Poland PAGE 26 Where to look for a job? PAGE 26 Polish culture PAGE 27 Food PAGE 30 Prices and expenses in Poland PAGE 32 Formalities PAGE 33 Basic Polish phrases PAGE 34 Hello, Together with the Students’ Parliament of the Republic of Poland (PSRP), the European Student Network (ESN) Poland we welcome you to Poland. -

AMU Welcome Guide | 5 During the 123 Years Following the 1795 and German, Offered by 21 Faculties on 1

WelcomeWelcome Guide Guide Welcome Guide The Project is financed by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange under the Welcome to Poland Programme, as part of the Operational Programme Knowledge Education Development co-financed by the European Social Fund Welcome from the AMU Rector 3 Welcome from AMU Vice-Rector for International Cooperation 4 1. AdaM Mickiewicz UniversitY 6 1.1. Introduction 6 1.2. International cooperation 7 1.3. Faculties 9 Poznań campus 9 Kalisz campus – Faculty of Fine Arts and Pedagogy 9 Gniezno campus – Institute of European Culture 10 Piła campus – Nadnotecki Institute 10 Słubice campus – Collegium Polonicum 10 1.4. Main AMU Library (ul. Ratajczaka, Poznań) 11 1.6. School of Polish Language and Culture 13 2. Study witH us! 14 2.1. Calendar 14 Table of 2.2. International Centre is here to help! 16 2.3. Admission 17 Content 2.3.1. Enrolment in short 21 2.4. Dormitories 23 2.5. NAWA Polish Governmental Scholarships 24 2.6. Student organizations and Science Clubs 26 2.7. Activities for Students 27 3. LivinG In POlanD 32 3.1. Get to know our country! 32 3.2. Travelling around Poland 34 3.3. Health care 37 3.4. Everyday life 40 3.5. Weather 45 3.6. Documents 47 3.7. Migrant Info Point 49 4. PoznaŃ anD WIelkopolska – your neW home! 50 4.1. Welcome to our region 50 4.2. Explore Poznań 51 4.3. Cultural offer 57 4.4. Be active 60 4.5. Make Polish Friends 61 4.6. Enjoy life 62 4.7. -

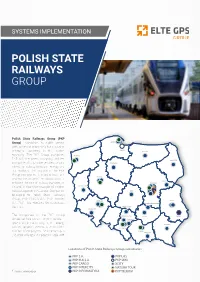

Implementation for Polish State Railways Group

SYSTEMS IMPLEMENTATION POLISH STATE RAILWAYS GROUP Polish State Railways Group (PKP Group) combines its public service GDYNIA with activity characteristic for a modern GDAŃSK enterprise operating in the market OLSZTYN economy. The PKP Group comprises SZCZECIN PKP S.A., the parent company, and ten BIAŁYSTOK companies that provide services, among BYDGOSZCZ others, on railway transport, energy and ICT markets. The mission of the PKP Group companies is to build trust and POZNAŃ improve the image of the railway, so as to SIEDLCE enhance the role of railway transport in WARSZAWA Poland, following the example of modern ZIELONA GÓRA railways operating in Europe. Companies ŁÓDŹ belonging to Polish State Railways Group: PKP CARGO S.A., PKP Intercity WROCŁAW LUBLIN S.A., PKP Linia Hutnicza Szerokotorowa SKARŻYSKO-KAMIENNA Sp. z o.o.. CZĘSTOCHOWA WAŁBRZYCH The companies of the PKP Group TARNOWSKIE GÓRY KIELCE ZAMOŚĆ altogether hire almost 70,000 people – SOSNOWIEC specialists in the railway, IT, ICT, energy RZESZÓW and real property sectors. In terms of the KATOWICE KRAKÓW number of employees, the PKP Group is NOWY SĄCZ the second largest employer in Poland.[1] Locations of Polish State Railways Group subsidiaries. PKP S.A. PKP LHS PKP PLK S.A. PKP SKM PKP CARGO XCITY PKP INTERCITY NATURA TOUR [1] Source: www.pkp.pl PKP INFORMATYKA PKP TELKOM ET GPS Positioning system The ET GPS system is designed to monitor the position of locomotives and wagons. GPS tracker saves the object location, speed, direction of movement and information from sensors and interfaces. The data saved in the internal memory of the GPS tracker are transferred to the monitoring system. -

Dziennik Urzędowy 18/2020

DZIENNIK URZĘDOWY PREZESA URZĘDU TRANSPORTU KOLEJOWEGO Warszawa, dnia 29 grudnia 2020 r. Poz. 18 DECYZJA DPP-WOPN.717.7.2018.KŚ PREZESA URZĘDU TRANSPORTU KOLEJOWEGO z dnia 26 listopada 2020 r. w sprawie przyznania POLREGIO otwartego dostępu dla pasażerskich przewozów kolejowych na trasie Łódź Kaliska – Kraków Główny – Łódź Kaliska. Na podstawie art. 13 ust. 1 pkt 5 w związku z art. 29c ust. 1, 3, 5, 6 oraz art. 13a ust. 1 ustawy z dnia 28 marca 2003 r. o transporcie kolejowym (tekst jednolity: Dz. U. z 2020 r. poz. 1043, z późn. zm.), zwanej dalej „ustawą o transporcie kolejowym”, związku z art. 4 ustawy z dnia 13 lutego 2020 r. o zmianie ustawy o transporcie kolejowym oraz niektórych innych ustaw (Dz. U. poz. 400), art. 15 ust. 1 rozporządzenia wykonawczego Komisji (UE) nr 869/2014 z dnia 11 sierpnia 2014 r. w sprawie nowych kolejowych przewozów pasażerskich (Dz. Urz. UE L 239 z 12 sierpnia 2014 r., str. 1), zwanego dalej „rozporządzeniem 869/2014”) oraz art. 104 § 1 ustawy z dnia 14 czerwca 1960 r. – Kodeks postępowania administracyjnego (tekst jednolity: Dz. U. z 2020 r. poz. 256, z późn. zm.), zwanej dalej „k.p.a.”, po rozpoznaniu wniosku spółki „Przewozy Regionalne” sp. z o.o. z siedzibą w Warszawie (obecnie: POLREGIO sp. z o.o.), zwanej dalej również „POLREGIO” lub „Przewoźnikiem”, z 22 marca 2018 r. (data wpływu do Urzędu Transportu Kolejowego, zwanego dalej „UTK”: 26 marca 2018 r.), w przedmiocie wydania przez Prezesa Urzędu Transportu Kolejowego, zwanego dalej „Prezesem UTK”, lub „organem regulacyjnym”, decyzji o przyznaniu otwartego dostępu na trasie Łódź Kaliska – Kraków Główny – Łódź Kaliska na okres od 1 stycznia 2020 r. -

Rok 2019 W Przewozach Pasażerskich I Towarowych Podsumowanie Urzędu Transportu Kolejowego Nasza Misja

ROK 2019 W PRZEWOZACH PASAŻERSKICH I TOWAROWYCH PODSUMOWANIE URZĘDU TRANSPORTU KOLEJOWEGO NASZA MISJA Kreowanie bezpiecznych i konkurencyjnych warunków świadczenia usług transportu kolejowego NASZA WIZJA Nowoczesny i otwarty urząd dbający o wysokie standardy wykonywania usług na rynku transportu kolejowego 2 Urząd Transportu Kolejowego Al Jerozolimskie 134 02-305 Warszawa www.utk.gov.pl dr inż. Ignacy Góra Prezes Urzędu Transportu Kolejowego Szanowni Państwo, w 2019 r. z kolei skorzystało ponad 335 milionów pasażerów, podczas gdy jeszcze w 2016 r. wartość ta nie przekraczała 300 milionów. Długość zrealizowanych przez pasażerów kolei przejazdów to łącznie ponad 22 miliardy kilometrów. Znaczna część tych podróży mogłaby się zapewne odbyć prywatnymi samochodami. Jednak samochody te nie pojawiły się na drogach, nie przejechały miliardów kilometrów – dzięki kolei podróżowanie było bezpieczniejsze i bardziej ekologicznie. Kolej pełni obecnie funkcję wykorzystywanej codziennie doskonałej komunikacji aglomeracyjnej i miejskiej oraz jest chętnie wybierana podczas dalekich podróży turystycznych czy biznesowych. W przypadku transportu towarowego przewieziono 236 milionów ton ładunków. Oznacza to spadek przetransportowanej masy o 5,5%. Jednak o ile zauważalne jest zmniejszenie się zainteresowania transportem towarów masowych, to z roku na rok rośnie masa przewozów intermodalnych. Ten rodzaj transportu ma przed sobą przyszłość i należy go rozwijać. Szczególnie, że dzięki transportowi intermodalnemu optymalnie można wykorzystać transport samochodowy, kolejowy i morski. Wyniki za 2019 r. pokazują, że kolej staje się coraz bardziej dostępna. Powstają nowoczesne dworce i perony, pociągi wracają na trasy od lat nieużywane, zwiększa się dostępność kolei dla osób z niepełnosprawnością i o graniczonej możliwości poruszania się, wykorzystywane są nowoczesne kanały dystrybucji itd. Jeszcze jest wiele do zrobienia, ale od kilku lat poprawia się jakość podróżowania i znajduje to potwierdzenie w statystykach. -

Regulamin Przewozu (Rpr)

Tekst ujednolicony ze zmianami nr 1 – 3 POLREGIO spółka z ograniczoną odpowiedzialnością REGULAMIN PRZEWOZU (RPR) Obowiązuje od 15 maja 2019 r. Podstawa prawna: Uchwała Nr 160/2019 Zarządu ”Przewozy Regionalne” sp. z o.o., z dnia 6 maja 2019 r. ZMIANY REGULAMINU PRZEWOZU (RPR) Nr Podstawa wprowadzenia zmiany Nr rozdziałów, paragrafów, Zmiana Podpis porządkowy w których wprowadzono obowiązuje osoby zmiany zmianę od dnia wnoszącej Nr Data zmianę Decyzja nr 22/2019 Spis treści; §§ 1, 2, 14, 19, 1. Członka Zarządu – Dy- 30.05.2019 r. 09.06.2019 r. 20, 27. rektora Handlowego Decyzja nr 39/2019 §§ 1, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 2. Członka Zarządu – 30.08.2019 r. 06.09.2019 r. 24. Dyrektora Handlowego Decyzja nr 22/2020 Strona tytułowa; §§ 1, 2, 9, 3. Członka Zarządu – 26.03.2020 r. 01.04.2020 r. 12, 14, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31. Dyrektora Handlowego 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. UWAGA: Przy wprowadzeniu zmiany w tekście należy wskazać jej numer porządkowy. 2 SPIS TREŚCI ZMIANY REGULAMINU PRZEWOZU (RPR) ................................................................................. 2 ROZDZIAŁ 1 POSTANOWIENIA OGÓLNE .................................................................................. 4 § 1 Słownik stosowanych terminów ............................................................................................. 4 § 2 Zakres Regulaminu przewozu (RPR) .................................................................................... 6 § 3 Przepisy porządkowe ...........................................................................................................