Robert Frank Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

BILL BRANDT Thames & Hudson

ART+PHOTOGRAPHY SPRING 2013 Shadow & Light BILL BRANDT Thames & Hudson www.state-media.com BOOK SPRING 2013 | 1 THE BEST OF BRANDT FROM THAMES & HUDSON NORMAN CORNISH A SHOT AGAINST TIME The storryy of Norman Cornish’s prodigious career as an arrttist who converrtted his experience as a miner into compelling imagerryy has become justly famous. Born in 1919, in Spennymoorr,, Co Durham, Norman Cornish was apprenticed at the age of 14 at the Dean and Chapter Collierryy (also known as the Butcher’s Shop), and spent the next 33 years working in various pits in the Norrtth East of England. Without diminishing the harsh Bill Brandt realities of life and work during those years, his paintings create a sense Shadow and Light of time and place by depicting the lyrical qualities of his surroundings in Sarah Hermanson Meister which time is defeated. Foreword by Glenn D. Lowry ‘Fantastic … well-written Long before the Angel of the Norrtth, Cornish’s work was loved and and interesting’ admired as a symbol of the Norrtth East. For all that the mines have closed, Amateur Photographer his work continues to be an enduring testament to a community whose ISBN 978 0 500 544242 £34.95 spirit surrvvives triumphantly. Brandt Nudes A New Perspective Preface by Lawrence Durrell Foreword by Mara-Helen Wood Commentaries by Mark Haworth-Booth Essays by William Feaververr,, William Varleyy,, Michael Chaplin and Dr Gail-Nina Anderson 140 of Bill Brandt’s classic and dramatic nudes, brought together Paperback, 160pp with 134 full colour illustrations in one beautiful -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Helmut Newton

GALERIE ANDREA CARATSCH HELMUT NEWTON BIOGRAPHY SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS * catalogue or publication 2012 HELMUT NEWTON RETROSPECTIVE Grand Palais, Paris, France 2011 SELECTED WORKS Hamiltons Gallery, London, UK WERKE AUS EINER BREMER PRIVATSAMMLUNG/MUSEUM DER MODERNE SALZBURG Kunsthaus Apolda Avangarde, Apolda, Germany HELMUT NEWTON – POLAROIDS Helmut Newton Foundation, Berlin, Germany HELMUT NEWTON: WHITE WOMEN. SLEEPLESS NIGHTS. BIG NUDES The Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Houston, TX, USA 2009 A GUN FOR HIRE Fundación Caixa Galicia, La Coruña, Spain WERKE AUS EINER BREMER PRIVATSAMMLUNG Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso, Munster, Germany HELMUT NEWTON Hamiltons Gallery, London, UK SUMO Helmut Newton Foundation, Berlin, Germany 2008 HELMUT NEWTON La Fábrica Galería, Madrid, Spain WERKE AUS EINER BREMER PRIVATSAMMLUNG Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst, Bremen, Germany HELMUT NEWTON – FIRED Helmut Newton Foundation, Berlin, Germany 2007 WANTED Helmut Newton, Larry Clark, Ralph Gibson at the Helmut Newton Foundation, Berlin, Germany HELMUT NEWTON XL Hamiltons Gallery, London, UK 72 ORE A ROMA Shenker Culture Club, Torino, Italy HELMUT NEWTON Cook Fine Art, New York, NY, USA VIA SERLAS 12 CH-7500 ST.MORITZ TEL +41 81 734 0000 FAX +41 81 734 0001 [email protected] GALERIE ANDREA CARATSCH 2006 SEX & LANDSCAPES Palazzo Reale , Milan, Italy YELLOW PRESS Playboy Projections, Guest Artist: Veruschka Self-Portraits, Performed by Vera Lehndorff, Photographed by Andreas Hubertus Ilse, at the Helmut Newton Foundation, Berlin, Germany MEN, WAR & -

ARNO RAFAEL MINKKINEN Born Helsinki, Finland 1945 Education

ARNO RAFAEL MINKKINEN Born Helsinki, Finland 1945 Education 1974 Master of Fine Arts in Photography, Rhode Island School of Design The New School for Social Research The School of Visual Arts 1967 Bachelor of Arts in English, Wagner College Grants/Awards 2015 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship 2013 Lucie Award for Achievement in Fine Art. Lucie Foundation 2011 Nancy Donahue Professor of Art, University of Massachusetts Lowell 2008 Prix Pictet Finalist 2006 Finnish State Art Prize in Photography Special Jury Prize, Lianzhou International Photo Festival, Lianzhou, China Finnish Photographic Arts Council Book Grant: Homework: The Finnish Photographs of Arno Rafael Minkkinen 1998 President of the Jury, Images ‘98, Vevey, Switzerland 1996 Scritture d’Acqua Prize in Literature, Art & Science: Salsomaggiore, Italy 1994 Grand Prix du Livre for Waterline at the 25th Rencontres d’Arles, France 1992 Knighted by Finnish Government: Order of the Lion First Class Medal for promotion of Finnish Photography internationally 1991 National Endowment for the Arts Regional Fellowship Permanent Collections Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA Albin O. Kuhn Gallery, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, MD Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada Artothèque de Nice, France Artothèque de Grenoble, France Artothèque de Nantes, France Artothèque de Caen, France Bain & Company, Boston, MA Banque et Caisse d’Epargne du Luxembourg BC Partners, London, England Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France Bibliothèque Henri Vincenot, Talant, France Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon, Lyon, France The Celebrity Art Collection Solstice, Oslo, Norway 1637 W. Chicago Ave. • Chicago • p:312-266-2350 • [email protected] Page 2 / Minkkinen Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tempe, AZ Cherye R. -

An Exhibition of B&W Argentic Photographs by Olivier Meyer

An exhibition of b&w argentic photographs by Olivier Meyer Location Gonville & Caius College, Trinity Street, Cambridge Exhibition 29 & 30 September 2018 10 am—5 pm Contact [email protected] Avenue du Président Wilson. 1987 Olivier Meyer, photographer Olivier Meyer is a contemporary French photographer born in 1957. He lives and works in Paris, France. His photo-journalism was first published in France-Soir Magazine and subsequently in the daily France-Soir in 1981. Starting from 1989, a selection of his black and white photographs of Paris were produced as postcards by Éditions Marion Valentine. He often met the photographer Édouard Boubat on the île Saint-Louis in Paris and at the Publimod laboratory in the rue du Roi de Sicile. Having seen his photographs, Boubat told him: “at the end of the day, we are all doing the same thing...” When featured in the magazine Le Monde 2 in 2007 his work was noticed by gallery owner Charles Zalber who exhibited his photographs at the gallery Photo4 managed by Victor Mendès. Work His work is in the tradition of humanist photography and Street photography, using the same material as many of the forerunners of this style: Kodak Tri-X black and white film, silver bromide prints on baryta paper, Leica M3 or Leica M4 with a 50 or 90 mm lens. The thin black line surrounding the prints shows that the picture has not been cropped. His inspiration came from Henri Cartier-Bresson, Édouard Boubat, Saul Leiter. His portrait of Aguigui Mouna sticking his tongue out like Albert Einstein, published in postcard form in 1988, and subsequently as an illustration in a book by Anne Gallois served as a blueprint for a stencil work by the artist Jef Aérosol in 2006 subsequently reproduced in the book VIP. -

The Nude – Photographs 1850-1980

Alfred Stieglitz. Georgia O’Keeffe – A Portrait. New York: Viking Press/Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978. TR681 .F3 S75 1978 Constance Sullivan. The Nude – Photographs 1850-1980. New York: Harper & Row, 1980. TR675 .N83 1980 Library Reader Resources Series #9 Arthur Tress. Fantastic Voyage – Photographs 1956-2000. New York: Bullfinch/Corcoran Gallery, 2001. TR647 .L663 2001 The Nude Peter Weiermair. Wilhelm Von Gloeden. Koln: Taschen, 1996. TR675.G475 1993 Thomas Waugh. Hard to Imagine – Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film from Their Beginnings to Stonewall. New York: Columbia University, 1996. TR681 .H65 W38 1996 Bruce Weber. Branded Youth & Other Stories. Boston: Bullfinch Press, 1997. TR681 .M4 .W43 1997 Peter Weiermair. The Hidden Image. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1988. TR675.W45 1988 Edward Weston. Nudes. New York: Aperture, 1977. TR675.W47 1977. TR675 .W45 1988 Joel-Peter Witkin & Stanley Burns. Masterpieces of Medical Photography from the Burns Archive. Pasadena: Twelvetrees Press, 1987. TR708 .M37 1987 Francesca Woodman. New York: Scalo/Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 1998. TR140 .W66 1998 Bunny Yeager. How I Photograph Nudes. A.S. Barnes, 1963. TR678 .Y43 1963 Cover: Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952) [Man posed on rocks, playing pipe (Pan)] cyanotype, 1885 - 1900 International Center of Photography Library 1114 Avenue of the Americas, Concourse New York NY 10036-7703 Readers Resource #9 was compiled for ICP Library by (212) 857-0004 tel / (212) 857-0091 fax Bernard Yenelouis, revised for LC Classification 9/2009. [email protected] Malek Alloula. The Colonial Harem. Minneapolis: George Platt Lynes. Photographs 1931-1955. Pasadena: University of Minnesota, 1986. TR681 .W6 .A76 1986 Twelvetrees Press, 1983. -

HENI Publishing Catalogue 2019

Since its inception in 2009, HENI Publishing has worked closely with artists and authors of the highest calibre across a wide range of titles, from major trade publications to artists’ books and limited editions. Among our new titles for 2019 we are delighted to be publishing the collected conversations of two titans of the contemporary art world in Hans Ulrich Obrist’s The Richter Interviews; a new monograph on New York- based British artist Shantell Martin, the first critical book to showcase her multi-faceted practice; a beautiful and intimate survey of nude photography by Mary McCartney, complete with an artist’s special edition; an artist’s book by Cathy Wilkes to accompany her exhibition at the British Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale; and the first of two volumes of the collected writings on art by one of the world’s leading critics and curators, Robert Storr. To find out more about our books – as well as HENI’s work across editions, film, photography and more – visit our website: www.heni.com Contents New Titles 2019 5 Recent Titles & Backlist 29 List of Illustrations 45 Index 46 Sales & Distribution 48 New Titles 2019 Mary McCartney: Paris Nude Essay by Charlotte Jansen Paris Nude presents for the first time a new body of work by the celebrated British photographer Mary McCartney. Over the course of two days in summer 2016, McCartney stayed with her subject Phyllis Wang at her St Germain apartment in Paris, photographing Wang in the nude to produce an extraordinary and intimate series of images. A mixture of black-and-white and colour, the delicate photo- graphs collected here showcase the trust required from both subject and photographer. -

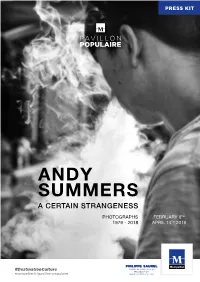

Andy Summers

PRESS KIT “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” Pavillon Populaire - From February 6th to April 14th 2019 ANDY SUMMERS A CERTAIN STRANGENESS PHOTOGRAPHS FEBRUARY 6TH 1979 - 2018 APRIL 14TH 2019 #DestinationCulture montpellier.fr/pavillon-populaire “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” Pavillon Populaire - From February 6th to April 14th 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” at the Pavillon Populaire in Montpellier from February 6th to April 14th 2019 . 4 Text of intent – Gilles Mora, artistic director of the Pavillon Populaire . 7 Text of intent – Andy Summers . 9 Artist’s biography . 10 2019 Pavillon Populaire programme . 11 Pavillon Populaire: photography made accessible for all. 12 Montpellier, a cultural destination . 13 Montpellier, a candidate for the European Capital of Culture . 17 Press images . 18 2 “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” Pavillon Populaire - From February 6th to April 14th 2019 A WORD FROM PHILIPPE SAUREL The Pavillon Populaire 2018 season – dedicated to the link between history and photography – has been truly outstanding with more than 130 000 visitors for three exhibitions. In 2019, the Pavillon Populaire puts on a new event with the world of Andy Summers, photographer and guitarist of the mythic 80’s rock band The Police. Through his exhibition “A certain strangeness, photographs 1977-2018”, the artist presents us a dense masterpiece, quite similar to a private diary in form of pictures. With more than 250 images, most of which are yet unseen, the exhibition includes the series “Let’s get weird!”, a lucid and corrosive outlook on the ascent of the famous 80’s band. -

CHURCH-STATE RECIPROCITY in CONTEMPORARY BRAZIL the Convening of the International Eucharistic Congress of 1955 in Rio De Janeiro

CHURCH-STATE RECIPROCITY IN CONTEMPORARY BRAZIL The Convening of the International Eucharistic Congress of 1955 in Rio de Janeiro Kenneth P. Serbin Working Paper #229 - August 1996 Kenneth P. Serbin, a Visiting Fellow at the Kellogg Institute (spring 1992), is Assistant Professor of History at the University of San Diego. He has researched the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil since 1986 and received his PhD in Latin American History in 1993 from the University of California, San Diego. His most recent article, “Brazil: State Subsidization and the Church since 1930,” was published in Organized Religion in the Political Transformation of Latin America, ed. Satya Pattnayak (New York: University Press of America, 1995). He is also the author of “Os seminários: crise, experiências, síntese” in Catolicismo: Modernidade e tradição, ed. Pierre Sanchis (São Paulo: Edições Loyola, 1992). During the 1992–93 academic year he had an appointment as Research Associate at the North-South Center at the University of Miami, where he published studies of the Latin American bishops and the Brazilian political crisis. He is currently writing two books on the Brazilian Church. A revised version of this paper will be published in the November 1996 issue of the Hispanic American Historical Review. The author wishes to thank Ralph Della Cava, Pedro A. Ribeiro de Oliveira, Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman, Marina Bandeira, Dain Borges, Eric Van Young, and several anonymous readers for their excellent comments on earlier versions and also those who remarked on a presentation of these findings at the Second General Conference of the Commission for the Study of the History of the Church in Latin America, São Paulo, Brazil, 25–28 July 1995. -

International Photography Hall of Fame Announces 2019 Inductees

International Photography Hall of Fame Announces 2019 Inductees Eight inductees and a special Lifetime Achievement Award recipient will be honored at special induction ceremony on November 1, 2019 in St. Louis ST. LOUIS, April 3, 2019 – The International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum (IPHF) is pleased to announce its 2019 class of Photography Hall of Fame inductees, and will honor them at its 2019 Hall of Fame Induction and Awards Ceremony on Friday, November 1 at .ZACK in the Grand Center Arts District in St. Louis. The IPHF annually awards and inducts notable photographers or photography industry visionaries for their artistry, innovation, and significant contributions to the art and science of photography. 2019 Honorees to be inducted into the Hall of Fame include the following eight photographers or photography industry visionaries who demonstrate the artistry, passion and revolution of the past and present art and science of photography: • Bruce Davidson, Social/Civil Rights photographer • Elliott Erwitt, Advertising/Documentary photographer • Ralph Gibson, Art photographer • Mary Ellen Mark, Documentary/Portrait photographer • Steve McCurry, Award-winning photographer • Paul Nicklen, Conservationist photographer • Olivia Parker, Still-life photographer • Tony Vaccaro, Photojournalist/WWII photographer The 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award honoree will be named at a later date. "The diversity of work and offerings from this year's awardees provides for a full range of fabulous photography. We are proud to bring them into the Hall of Fame," said Richard Miles, Chairman of the Board of IPHF. A nominating committee of IPHF representatives and notable photographic leaders with a passion for preserving and honoring the art of photography selected the inductees. -

Robert Frank Map and Chronology

8kjj[ :[jhe_j D[mOeha9_jo 9b[l[bWdZ 9^_YW]e IWd<hWdY_iYe ?dZ_WdWfeb_i IWdjW<[ Bei7d][b[i IWlWddW^ D[mEhb[Wdi >ekijed Ij$F[j[hiXkh] C_Wc_ 1924 1946 November 9: Robert Louis Frank is Makes spiral-bound book 40 Fotos, born in Zurich, Switzerland, the incorporating original photographs second son of Regina and Hermann in various genres. Frank. Travels to Milan, Paris, and Strasbourg. 1931 – 1937 May – August: Works for Graphic Attends Gabler School, Zurich. Atelier H., R. and W. Eidenbenz, Map and Basel. 1937 – 1940 Chronology Attends Lavater Secondary School, 1947 Zurich. February 19 or 20: Departs Antwerp Sarah Gordon and Paul Roth on S.S. James Bennett Moore bound for Rotterdam and New York City. 1940 March 14: Arrives in New York, finds 8kjj[ Studies French at the Institut an apartment opposite Rockefeller Jomini, Payerne. Center, and lives briefly with the Note on Chronology designer and photographer Herbert Matter and his wife, Mercedes, in This chronology focuses on Frank’s 1941 Greenwich Village. Later moves to 53 :[jhe_j early years, with an emphasis on January: Begins informal apprentice- East Eleventh Street in Manhattan. D[mOeha9_jo 9b[l[bWdZ activities and associations related ship with photographer and graphic 9^_YW]e Late March / early April: Visits Henri to The Americans. It is indebted designer Hermann Segesser in Cartier-Bresson exhibition at the to Stuart Alexander, Robert Frank: Zurich (until March 1942). IWd<hWdY_iYe Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). ?dZ_WdWfeb_i A Bibliography, Filmography, and September – December: Serves as still Exhibition Chronology 1946 – 1985 April: Hired by Alexey Brodovitch photographer for film Landammann (Tucson: Center for Creative Photog- as an assistant photographer at Stauffacher.