Popular Music Education: Insights from Tabuley's 'Muzina'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Indépendance Cha Cha”: African Pop Music Since the Independence Era, In: Africa Spectrum, 45, 3, 131-146

Africa Spectrum Dorsch, Hauke (2010), “Indépendance Cha Cha”: African Pop Music since the Independence Era, in: Africa Spectrum, 45, 3, 131-146. ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs in co-operation with the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To subscribe to the print edition: <[email protected]> For an e-mail alert please register at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Africa Spectrum is part of the GIGA Journal Family which includes: Africa Spectrum • Journal of Current Chinese Affairs • Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs • Journal of Politics in Latin America • <www.giga-journal-family.org> Africa Spectrum 3/2010: 131-146 “Indépendance Cha Cha”: African Pop Music since the Independence Era Hauke Dorsch Abstract: Investigating why Latin American music came to be the sound- track of the independence era, this contribution offers an overview of musi- cal developments and cultural politics in certain sub-Saharan African coun- tries since the 1960s. Focusing first on how the governments of newly inde- pendent African states used musical styles and musicians to support their nation-building projects, the article then looks at musicians’ more recent perspectives on the independence era. Manuscript received 17 November 2010; 21 February 2011 Keywords: Africa, music, socio-cultural change Hauke Dorsch teaches cultural anthropology at Johannes Gutenberg Uni- versity in Mainz, Germany, where he also serves as the director of the Afri- can Music Archive. -

Dec 19, 2015 Fondation Cartier Traces the Creative Spirit of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Fondation Cartier Traces the C

dec 19, 2015 fondation cartier traces the creative spirit of the democratic republic of the congo fondation cartier traces the creative spirit of the democratic republic of the congo monsengo shula, ‘ata ndele mokili ekobaluka (tôt ou tard le monde changera)’, 2014 acrylic and glitters on canvas, 130 x 200 cm private collection © monsengo shula photo © florian kleinefen beauté congo – 1926-2015 – congo kitoko fondation cartier, paris on now until january 10th, 2016 the creative spirit of the democratic republic of the congo is celebrated in a special exhibition hosted at the fondation cartier in paris. curated by andré magnin, ‘beauté congo – 1926-2015 – congo kitoko’ highlights the birth of modern painting practices in the african nation beginning in the 1920s, and traces almost a century of the country’s artistic production. while the focus is on painting, the show also includes comics, music, photography and sculpture, offering the public a unique opportunity in which to discover and experience the diverse and vibrant art scene of the region. monsengo shula, ‘ata ndele mokili ekobaluka (tôt ou tard le monde changera)’, 2014 (detail) image © designboom 1 in the mid-1920s, when the congo was still a belgian colony, precursors such as albert and antoinette lubacki, and djilatendo painted the first known congolese works on paper, opening the door to the modern and contemporary art scene in the country. figurative and geometric in style, their works depicted village life, the natural world, dreams and legends expressed with great poetry and imagination. following world war II, french painter pierre romain-desfossés moved to the congo and established an art workshop called atelier du hangar, where until his death in 1954, painters such as bela sar, mwenze kibwanga and pili pili mulongoy learned to freely exercise their imaginations, creating colorful and enchanting works in their own inventive and distinctive styles. -

P32:Layout 1

TV PROGRAMS MONDAY, DECEMBER 2, 2013 Impossible 04:50 Suite Life On Deck 01:45 Dynamo: Magician 05:15 Wizards Of Waverly Place Impossible 05:35 Wizards Of Waverly Place 02:35 Dynamo: Magician 06:00 Austin And Ally John Galliano’s 00:20 Paradox Impossible 06:25 Austin And Ally 01:15 Hebburn 03:25 Dynamo: Magician 06:45 A.N.T. Farm case to be heard in 01:45 Absolutely Fabulous Impossible 07:10 A.N.T. Farm 02:15 Spooks 04:15 Dynamo: Magician 07:35 Gravity Falls a labour court 03:05 Last Of The Summer Wine Impossible 07:55 My Babysitter’s A Vampire 03:35 Luther 05:05 Dynamo: Magician 08:20 Sofia The First 04:30 Hebburn Impossible 08:45 Doc McStuffins ohn Galliano’s case against former employers 05:00 Nina And The Neurons 06:00 Mythbusters 09:05 Mickey Mouse Clubhouse Christian Dior Couture SA and John Galliano SA 07:00 Mythbusters 09:30 Shake It Up J 05:15 Poetry Pie will be heard in a labour court. The Paris Court of 07:50 Extreme Fishing 09:55 Austin And Ally 05:20 Mr Bloom’s Nursery Appeals rejected an appeal by Dior, which was seek- 05:40 Little Human Planet 08:40 Overhaulin’ 2012 10:15 A.N.T. Farm 10:40 Dog With A Blog ing to move the case to a commercial court, and 05:45 Bobinogs 09:30 Border Security 11:05 Jessie 05:55 Tweenies 09:55 Storage Hunters ordered the companies to each pay the fashion 11:25 Suite Life On Deck € 06:15 Nina And The Neurons 10:20 Property Wars designer 2,500, in addition to court costs. -

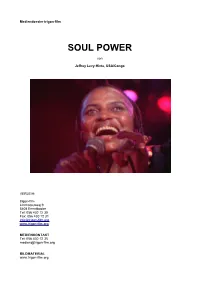

Pd Soul Power D

Mediendossier trigon-film SOUL POWER von Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, USA/Congo VERLEIH: trigon-film Limmatauweg 9 5408 Ennetbaden Tel: 056 430 12 30 Fax: 056 430 12 31 [email protected] www.trigon-film.org MEDIENKONTAKT Tel: 056 430 12 35 [email protected] BILDMATERIAL www.trigon-film.org MITWIRKENDE Regie: Jeffrey Levy-Hinte Kamera: Paul Goldsmith Kevin Keating Albert Maysles Roderick Young Montage: David Smith Produzenten: David Sonenberg, Leon Gast Produzenten Musikfestival Hugh Masekela, Stewart Levine Dauer: 93 Minuten Sprache/UT: Englisch/Französisch/d/f MUSIKER/ IN DER REIHENFOLGE IHRES ERSCHEINENS “Godfather of Soul” James Brown J.B.’s Bandleader & Trombonist Fred Wesley J.B.’s Saxophonist Maceo Parker Festival / Fight Promoter Don King “The Greatest” Muhammad Ali Concert Lighting Director Bill McManus Festival Coordinator Alan Pariser Festival Promoter Stewart Levine Festival Promoter Lloyd Price Investor Representative Keith Bradshaw The Spinners Henry Fambrough Billy Henderson Pervis Jackson Bobbie Smith Philippé Wynne “King of the Blues” B.B. King Singer/Songwriter Bill Withers Fania All-Stars Guitarist Yomo Toro “La Reina de la Salsa” Celia Cruz Fania All-Stairs Bandleader & Flautist Johnny Pacheco Trio Madjesi Mario Matadidi Mabele Loko Massengo "Djeskain" Saak "Sinatra" Sakoul, Festival Promoter Hugh Masakela Author & Editor George Plimpton Photographer Lynn Goldsmith Black Nationalist Stokely Carmichael a.k.a. “Kwame Ture” Ali’s Cornerman Drew “Bundini” Brown J.B.’s Singer and Bassist “Sweet" Charles Sherrell J.B.’s Dancers — “The Paybacks” David Butts Lola Love Saxophonist Manu Dibango Music Festival Emcee Lukuku OK Jazz Lead Singer François “Franco” Luambo Makiadi Singer Miriam Makeba Spinners and Sister Sledge Manager Buddy Allen Sister Sledge Debbie Sledge Joni Sledge Kathy Sledge Kim Sledge The Crusaders Kent Leon Brinkley Larry Carlton Wilton Felder Wayne Henderson Stix Hooper Joe Sample Fania All-Stars Conga Player Ray Barretto Fania All Stars Timbali Player Nicky Marrero Conga Musician Danny “Big Black” Ray Orchestre Afrisa Intern. -

Revisedphdwhole THING Whizz 1

McGuinness, Sara E. (2011) Grupo Lokito: a practice-based investigation into contemporary links between Congolese and Cuban popular music. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/14703 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. GRUPO LOKITO A practice-based investigation into contemporary links between Congolese and Cuban popular music Sara E. McGuinness Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2011 School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

(Inter)Textuality in Contemporary Kenyan Popular Music

"READING THE REFERENTS": (INTER)TEXTUALITY IN CONTEMPORARY KENYAN POPULAR MUSIC Joyce Wambũi Nyairo A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Johannesburg, 2004 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted for any other degree or examination in any other university. ___________________________ Joyce Wambũi Nyairo Fifth day of October, 2004. i Abstract This study explores the meaning of contemporary Kenyan popular music by undertaking literary interpretations of song lyrics and musical styles. In making these interpretations, the fabric of popular song is shown to be a network of referents and associations with texts situated both within and outside of the song-texts. As polyphonic discourse, these vast range of textual and paratextual referents opens up various points of engagement between artiste, songtext and audience and in the process, the surplus meanings generated by both the poetry of the text and the referents embedded within it account for the significance of popular songs as concrete articulations that mediate the realities of modern Kenya. Through the six chapters that make up the core of the study we see the mini-dramas that are played out in the material conditions within which the songs are produced; in the iconographies that are generated by artistes' stage names and album titles; in the strategies of memory work that connect present-day realities to old cultural practices; in the soundtracks of urban spaces and in those of domesticated global cultural trends and finally, in the mediation of the antinomies surrounding the metanarrative of the nation and the realization of political transition. -

Dancing Double Binds: Feminine Virtue and Women's Work in Kinshasa

Université de Montréal Dancing Double Binds: Feminine Virtue and Women’s Work in Kinshasa par Lesley Nicole Braun Département d’anthropologie Faculté des arts et sciences Thèse présentée a la Faculté des études supérieures En vue de l’obtention du grade du doctorat en anthropologie Août 2014 © Lesley Nicole Braun, 2014 Résumé Les femmes de Kinshasa, en République Démocratique du Congo, ont toujours été actives dans le commerce local. L’élévation de leur niveau d’études, ainsi que des circonstances économiques difficiles nécessitant deux salaires par famille, les poussent aujourd’hui vers de nouveaux métiers. Alors qu’elles deviennent plus visibles dans les sphères politiques et économiques, elles sont sujettes à de nouvelles formes de méfiance et d’accusation morale. C'est dans ce contexte que les notions de féminité et de vertu féminine sont définies aujourd'hui. Lorsque les femmes congolaises émigraient vers la ville de Léopoldville à l’ère coloniale, elles étaient confrontées à de nouvelles attentes sociales. Il était attendu qu’elles se « modernisent » et se « civilisent » tout en gardant leur rôle « traditionnel » au foyer et auprès de leur famille. Je voudrais démontrer que ce paradoxe continue d’influencer les représentations de la vertu féminine à Kinshasa aujourd'hui, notamment en établissant une distinction entre la femme « vertueuse » et « non vertueuse ». Cette thèse explore les façons dont les femmes participent et négocient leur nouveau statut et rôle à la lumière de ce paradoxe. Plutôt que de réifier la dichotomie locale entre la femme « vertueuse » et « non vertueuse », j’explore les causes sous-jacentes et les résultats inattendus de ces catégorisations. -

Music and Other Performing Arts for Sustainable Development Kabarak University, Nakuru, Kenya, 24Th – 26Th October 2018

Kabarak University International Research Conference on Refocusing Music and Other Performing Arts for Sustainable Development Kabarak University, Nakuru, Kenya, 24th – 26th October 2018 Conference Proceedings Kabarak University International Research Conference on Refocusing Music and Other Performing Arts for Sustainable Development Kabarak University, Nakuru, Kenya 24th – 26th October 2018 Page 1 of 92 Kabarak University International Research Conference on Refocusing Music and Other Performing Arts for Sustainable Development Kabarak University, Nakuru, Kenya, 24th – 26th October 2018 Editors 1. Dr Christopher Maghanga 2. Prof Mellitus Wanyama 3. Dr Moses M Thiga Page 2 of 92 Kabarak University International Research Conference on Refocusing Music and Other Performing Arts for Sustainable Development Kabarak University, Nakuru, Kenya, 24th – 26th October 2018 Sponsors This conference was graciously sponsored by the National Research Fund Page 3 of 92 Kabarak University International Research Conference on Refocusing Music and Other Performing Arts for Sustainable Development Kabarak University, Nakuru, Kenya, 24th – 26th October 2018 Foreword Dear Authors, esteemed readers, It is with deep satisfaction that I write this foreword to the Proceedings of the Kabarak University 8 th Annual International Research Conference held between 22nd and 26th October at the Kabarak University Main Campus in Nakuru, Kenya. This conference focused on the thematic areas of computer, education, health, business and music and attracted a great number -

The-Rumba-Kings-Press-Kit-June-2021-ENG.Pdf

OVERVIEW GENRE: Documentary Film RUNNING TIME: 94 minutes FORMAT: HD ASPECT RATIO: 16:9 DIRECTOR: Alan Brain - [email protected] PRODUCER: Monica Carlson - [email protected] LANGUAGES: French and Lingala (with English Subtitles) FOREIGN VERSION: Subtitles for the film are available in Spanish, English and French. PRODUCTION COMPANY: Shift Visual Lab LLC CONTACT: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.therumbakings.com FULL PRESS KIT: www.therumbakings.com/press THE RUMBA KINGS - PRESS KIT PAGE 2 "WE HAVE DIAMONDS, GOLD, COLTAN, AND ALL THAT. BUT MUSIC IS ALSO WEALTH." Simaro Lutumba THE RUMBA KINGS - PRESS KIT PAGE 3 PRESS RELEASE March 20, 2021 Our connection with the giant country in the center of Africa known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo is stronger than we may imagine. We all carry a bit of Congo in our pockets. All smartphones use a metal called coltan and Congo holds 80% of the world’s reserve of this mineral. Nevertheless, despite having some of the world's largest mineral deposits of coltan, cobalt, copper, gold, and diamonds, Congo has rarely seen real prosperity. The mining of those minerals has only brought division, wars and poverty to the Congolese people. What has brought them unity, happiness and hope is something else, something that was always there. Literally, from the beginning of time… The documentary film The Rumba Kings shows us that the real treasure of Congo has always been its music, specifically Congolese rumba music, the rhythm that helped Congo fight colonial oppression, that became the soundtrack to the country’s independence and that took Africa by storm with its mesmerizing guitar sounds. -

Download Press

A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE AN ANTIDOTE FILMS PRODUCTION A JEFFREY LEVY-HINTE FILM SOUL POWER Directed by Jeffrey Levy-Hinte Produced by David Sonenberg Leon Gast Originally Conceived by Stewart Levine Music Festival Producers Hugh Masekela Stewart Levine Edited by David Smith Featuring James Brown Bill Withers B.B. King The Spinners Celia Cruz and the Fania All-Stars Mohammad Ali Don King Stewart Levine …and many more Running Time: 93 Minutes East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP Public Relations Block-Korenbrot PR Sony Pictures Classics Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Leila Guenancia 853 7th Ave, 3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 Tel : 212-265-4373 Tel : 323-634-7001 Tel : 212-833-8833 SYNOPSIS In 1974, the most celebrated American R&B acts of the time came together with the most renowned musical groups in Africa for a 12-hour, three-night long concert held in Kinshasa, Zaire. The dream-child of Hugh Masekela and Stewart Levine, this music festival became a reality when they convinced boxing promoter Don King to combine the event with “The Rumble in the Jungle,” the epic fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, previously chronicled in the Academy Award-winning documentary WHEN WE WERE KINGS. SOUL POWER is a verité documentary about this legendary music festival (dubbed “Zaire ‘74”), and it depicts the experiences and performances of such musical luminaries as James Brown, BB King, Bill Withers, Celia Cruz, among a host of others. -

“Happy Are Those Who Sing and Dance:” Mobutu, Franco, and the Struggle for Zairian Identity

“HAPPY ARE THOSE WHO SING AND DANCE:” MOBUTU, FRANCO, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR ZAIRIAN IDENTITY A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Carter Grice Director: Dr. Beth Huber Associate Professor of English English Department Committee Members: Dr. Laura Wright, English Dr. Nate Kreuter, English November 2011 © 2011 by Carter Grice ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my committee director, Dr. Beth Huber, your astute, challenging, marvelously blunt style has intrigued me since our first class together. To my committee members, Dr. Laura Wright and Dr. Nate Kreuter, you both welcomed my project from the go and our meetings got me working and re- visioning. To my beautiful wife, Kelli, and our daughter, Laurel, you allowed this work to happen. To Dr. Marsha Lee Baker, and colleagues Alan Wray and Rain Newcomb, I have been significantly influenced by you all. To Franco Luambo Makiadi whose music has brought me joy that only human contact can exceed. In fact, his music is human contact of a most sublime sort. To Paulo Freire whose Pedagogy of the Oppressed provided the frame for this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract.……………………………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction ……………………………………………………………................... 6 Chapter One: “Luvumbu Ndoki” and the Pentecost Hanging........................... 21 Chapter Two: Franco vs. Mobutu: The Real Rumble....................................... 55 Chapter Three: A Sartorial Modernization........................................................ 83 Conclusion........................................................................................................ 105 ABSTRACT “HAPPY ARE THOSE WHO SING AND DANCE:” MOBUTU, FRANCO, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR ZAIRIAN IDENTITY Carter Grice, M.A. Western Carolina University (November 2011) Director: Dr. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Images des femmes et rapports entre les sexes dans la musique populaire du Zaïre Engundu, V.W. Publication date 1999 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Engundu, V. W. (1999). Images des femmes et rapports entre les sexes dans la musique populaire du Zaïre. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:05 Oct 2021 1 CHAPITRE 1 INTRODUCTION GENERALE Cette étude porte sur les représentations de la femme et les rapports entre les sexes tels qu'ils se reflètent dans la musique populaire en milieu urbain africain. Deux périodes contrastées de l'évolution de cette musique seront prises en considération. Seul ce critère de limitation dans le temps permettra de satisfaire notre souci de faire comprendre le rôle de l'usage des images de femmes dans la transmission du savoir populaire (Biaya 1988, Jewsiewicki 1984, 19861, Fabian 1996) à Kinshasa.