The Voiceless in Goan Historiography 1 19 Us in This Task

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

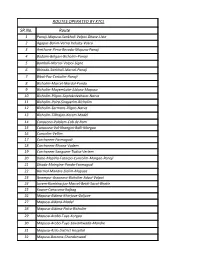

Wholesale List at Bardez

BARDEZ Sr.No Name & Address of The Firm Lic. No. Issued Dt. Validity Dt. Old Lic No. 1 M/s. Rohit Enterprises, 5649/F20B 01/05/1988 31/12/2021 913/F20B 23, St. Anthony Apts, Mapuca, Bardez- Goa 5651/F21B 914/F21B 5650/20D 24/20D 2 M/s. Shashikant Distributors., 6163F20B 13/04/2005 18/11/2019 651/F20B Ganesh Colony, HNo.116/2, Near Village 6164/F20D 652/F21B Panchyat Punola, Ucassim , Bardez – Goa. 6165/21B 122/20D 3 M/s. Raikar Distributors, 5022/F20B 27/11/2014 26/11/2019 Shop No. E-4, Feira Alto, Saldanha Business 5023/F21B Towers, Mapuca – Goa. 4 M/s. Drogaria Ananta, 7086/F20B 01/04/2008 31/03/2023 449/F20B Joshi Bldg, Shop No.1, Mapuca, Bardez- Goa. 7087/F21B 450/F21B 5 M/s. Union Chemist& Druggist, 5603/F20B 25/08/2011 24/08/2021 4542/F20B Wholesale (Godown), H No. 222/2, Feira Alto, 5605/F21B 4543/F21B Mapuca Bardez – Goa. 5604/F20D 6 M/s. Drogaria Colvalcar, 5925/F20D 09/11/2017 09/11/2019 156/F20B New Drug House, Devki Krishna Nagar, Opp. 6481/F20 B 157/F21B Fomento Agriculture, Mapuca, Bardez – Goa. 6482/F21B 121/F20D 5067/F20G 08/11/2022 5067/20G 7 M/s. Sharada Scientific House, 5730/F20B 07/11/1990 31/12/2021 1358/F20B Bhavani Apts, Dattawadi Road, Mapuca Goa. 5731/F21B 1359/F21B 8 M/s. Valentino F. Pinto, 6893/F20B 01/03/2013 28/02/2023 716/F20B H. No. 5/77A, Altinho Mapuca –Goa. 6894/F21B 717/F21B 9 M/s. -

Understanding the Response to Portuguese Missionary Methods in India in the 16Th – 17Th Centuries

UNDERSTANDING THE RESPONSE TO PORTUGUESE MISSIONARY METHODS IN INDIA IN THE 16TH – 17TH CENTURIES Christianity has had a very long history in the sub-continent. Even if the traditional belief of the arrival of one of the apostles of Jesus, St. Thomas is discounted, there is evidence to prove that Christian merchants from west Asia had sailed and settled on the west coast of India in the early centuries of the present era. Catholic missionaries, mainly of the Franciscan order arrived as early as the 13th century, in the northern reaches of the Indian west coast. Some of them were, in medieval terminology, even “martyred” for the faith.1 The arrival of the Portuguese, with their padroado (patronage) privileges however marks the first large-scale appearance of Christian missionaries in India. Despite such a longstanding Christian tradition the focus of Church history writing in India, in the context of it being written as a form of ‘mission history’ has always been on the agency, the agents and their work. This has meant that the overarching emphasis has been on the mission bodies, their practices and when it has concentrated on the local bodies, the numbers they were able to convert. Conversion stories have also been narrated, yet it is done with the view to highlight the activities of the mission and their underlying role in bringing about that conversion. This overemphasis on the work of the converting agencies was no doubt the consequence of the need to legitimize their work as well as the need for further financial and other forms of aid, but it has had several implications. -

List of Representation /Objection Received Till 31St Aug 2020 W.R.T. Thomas & Araujo Committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No

List of Representation /Objection Received till 31st Aug 2020 w.r.t. Thomas & Araujo committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No. Sy.No. Penha de Leflor, H.no 223/7. BB Borkar Road Alto 1 Bardez Leo Remedios Mendes 9822121352 181/5 Franca Porvorim, Bardez Goa Penha de next to utkarsh housing society, Penha 2 Bardez Marianella Saldanha 9823422848 118/4 Franca de Franca, Bardez Goa Penha de 3 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa 7821965565 151/1 Franca Penha de 4 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa nill 151/93 Franca Penha de H.No. 583/10, Baman Wada, Penha De 5 Bardez Ujwala Bhimsen Khumbhar 7020063549 151/5 Franca France Brittona Mapusa Goa Penha de 6 Bardez Mumtaz Bi Maniyar Haliwada penha de franca 8007453503 114/7 Franca Penha de 7 Bardez Shobha M. Madiwalar Penha de France Bardez 9823632916 135/4-B Franca Penha de H.No. 377, Virlosa Wada Brittona Penha 8 Bardez Mohan Ramchandra Halarnkar 9822025376 40/3 Franca de Franca Bardez Goa Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 9 Bardez 9765830867 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. 236/20, Ward III, Haliwada, penha 8806789466/ 10 Bardez Mahboobsab Saudagar 134/1 Franca de franca Britona, Bardez Goa 9158034313 Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 11 Bardez 9765830867 135/3, & 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. -

International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage

Abstract Volume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Abstract Volume: Intenational Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage 21th - 23rd August 2013 Sri Lanka Foundation, Colombo, Sri Lanka Editor Anura Manatunga Editorial Board Nilanthi Bandara Melathi Saldin Kaushalya Gunasena Mahishi Ranaweera Nadeeka Rathnabahu iii International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Copyright © 2013 by Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. First Print 2013 Abstract voiume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage Publisher International Association for Asian Heritage Centre for Asian Studies University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. ISBN 978-955-4563-10-0 Cover Designing Sahan Hewa Gamage Cover Image Dwarf figure on a step of a ruined building in the jungle near PabaluVehera at Polonnaruva Printer Kelani Printers The views expressed in the abstracts are exclusively those of the respective authors. iv International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 In Collaboration with The Ministry of National Heritage Central Cultural Fund Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology Bio-diversity Secratariat, Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy v International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Message from the Minister of Cultural and Arts It is with great pleasure that I write this congratulatory message to the Abstract Volume of the International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage, collaboratively organized by the Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Ministry of Culture and the Arts and the International Association for Asian Heritage (IAAH). It is also with great pride that I join this occasion as I am associated with two of the collaborative bodies; as the founder president of the IAAH, and the Minister of Culture and the Arts. -

Mouzinho Da Silveira and the Political Culture of Portuguese Liberalism

This article was downloaded by: [b-on: Biblioteca do conhecimento online UL] On: 03 June 2014, At: 04:32 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK History of European Ideas Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rhei20 Mouzinho da Silveira and the Political Culture of Portuguese Liberalism, 1820–1832 Nuno Gonçalo Monteiroa a Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Portugal Published online: 02 Jun 2014. To cite this article: Nuno Gonçalo Monteiro (2014): Mouzinho da Silveira and the Political Culture of Portuguese Liberalism, 1820–1832, History of European Ideas, DOI: 10.1080/01916599.2014.914311 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01916599.2014.914311 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010

– 1 – GOVERNMENT OF GOA The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010 – 2 – Edition: January 2017 Government of Goa Price Rs. 200.00 Published by the Finance Department, Finance (Debt) Management Division Secretariat, Porvorim. Printed by the Govt. Ptg. Press, Government of Goa, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Panaji-Goa – 403 001. Email : [email protected] Tel. No. : 91832 2426491 Fax : 91832 2436837 – 1 – Department of Town & Country Planning _____ Notification 21/1/TCP/10/Pt File/3256 Whereas the draft Regulations proposed to be made under sub-section (1) and (2) of section 4 of the Goa (Regulation of Land Development and Building Construction) Act, 2008 (Goa Act 6 of 2008) hereinafter referred to as “the said Act”, were pre-published as required by section 5 of the said Act, in the Official Gazette Series I, No. 20 dated 14-8- 2008 vide Notification No. 21/1/TCP/08/Pt. File/3015 dated 8-8-2008, inviting objections and suggestions from the public on the said draft Regulations, before the expiry of a period of 30 days from the date of publication of the said Notification in the said Act, so that the same could be taken into consideration at the time of finalization of the draft Regulations; And Whereas the Government appointed a Steering Committee as required by sub-section (1) of section 6 of the said Act; vide Notification No. 21/08/TCP/SC/3841 dated 15-10-2008, published in the Official Gazette, Series II No. 30 dated 23-10-2008; And Whereas the Steering Committee appointed a Sub-Committee as required by sub-section (2) of section 6 of the said Act on 14-10-2009; And Whereas vide Notification No. -

The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada's Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities

Brown Baby Jesus: The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada’s Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities Kathryn Carrière Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Religion and Classics Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Kathryn Carrière, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 I dedicate this thesis to my husband Reg and our son Gabriel who, of all souls on this Earth, are most dear to me. And, thank you to my Mum and Dad, for teaching me that faith and love come first and foremost. Abstract Employing the concepts of lifeworld (Lebenswelt) and system as primarily discussed by Edmund Husserl and Jürgen Habermas, this dissertation argues that the lifeworlds of Anglo- Indian and Goan Catholics in the Greater Toronto Area have permitted members of these communities to relatively easily understand, interact with and manoeuvre through Canada’s democratic, individualistic and market-driven system. Suggesting that the Catholic faith serves as a multi-dimensional primary lens for Canadian Goan and Anglo-Indians, this sociological ethnography explores how religion has and continues affect their identity as diasporic post- colonial communities. Modifying key elements of traditional Indian culture to reflect their Catholic beliefs, these migrants consider their faith to be the very backdrop upon which their life experiences render meaningful. Through systematic qualitative case studies, I uncover how these individuals have successfully maintained a sense of security and ethnic pride amidst the myriad cultures and religions found in Canada’s multicultural society. Oscillating between the fuzzy boundaries of the Indian traditional and North American liberal worlds, Anglo-Indians and Goans attribute their achievements to their open-minded Westernized upbringing, their traditional Indian roots and their Catholic-centred principles effectively making them, in their opinions, admirable models of accommodation to Canada’s system. -

Official Gazette Government ·Of Go~ Daman and Diu

REGD. GOA 51 Panaji, 28th July, 1977 (Sravana 6, 1899) SERIES III No. 17 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT ·OF GO~ DAMAN AND DIU GOVERNMENT OF GOA•. DAMAN AND DIU Home Department (Transport and A~commodation) Directorate of Transport Public Notice I - Applications have been received for grant of renewal of stage carriage permits to operate on the following routes :_ Date ot Date ot Sr. No. receipt expiry Name and address of the applicant M. V.No. 1. 16·5·77 20·9·77 Mis. Amarante & Saude Transport, Cuncolim, Salcete~Goa. Margao to GDT 2299 Mapusa via Ponda, Sanquelim. Bicholim & back. (Renewal of GDPst/ 396/70). 2. 6·6·77 21·11·77 Shri Sebastiao PaIha, H; No. 321, St. Lourenco, Agasaim, Ilhas-Goa. GDT 2188 Agasalm toPanaji & back. (Renewal of GDPst/98/66). 3. 6·6·77 26·12·77 Shri Sivahari Rama Tiloji, Gudem, Siolim, Bardez-Goa. SioUm to Mapusa GDT 2017 & back. (Renewal of GDPst/136/66). 4. 9·6·77 16·10·77 8hri Kashinath Bablo Naik, H. No. 83, Post Porvorim, Bardez-Goa. Mapusa GDT 2270 to Panaji & back (Renewal of GDPst/346/70). 5. 9·6·77 16·10·77 Shri Kashinath Bablo Naik, H. No. 83, Post Porvorim, Bardez-Goa. Mapusa GDT 2147 to Panaji & back. (Renewal of GDPst/345/70). 6. 15·6·77 28·12·77 Shri Arjun F. Ven~rIenkar, Baradi, Velim, Salcete-Goa. Betul to Margao GDT 2103 via Velim. Assolna, Cuncolim, Chinchinim & back. (Renewal of GDPst/ /151/66). 7. 24-6·77 3·11·77 Janata Transport Company, Curtorim, Salcete--Goa. -

Sr. No. Hotel Ctgry Name of the Hotel Address Ph. No. Taluka Rooms Beds 1 B Keni Hotels 18Th June Road, Panaji

Sr. Hotel Name of the Address Ph. No. Taluka Rooms Beds No. Ctgry Hotel 1 B Keni Hotels 18th June Road, Panaji - Goa 2224581 / 2224582 / Tiswadi 38 74 9822981148 / 9822104808 2 B Noah Ark Verem, Reis, Magos, Bardez, Goa 9822158410 Bardez 40 96 3 B Hotel Republica Opp. Old Govt. Secretariat, Panaji-Goa. 9422061098 / 2224630 Tiswadi 24 48 4 B Hotel Solmar D B Road, Miramar, Panaji-Goa. 403001 2464121 / 2462155 / Tiswadi 38 38 9823086402 5 B Hotel Delmon Caetano De Albuquerque Road, Panaji-Goa. 2226846/47 / Tiswadi 55 110 9850596727 / 7030909617 6 B Hotel Baia Do Baga Beach, Calangute, Bardez - Goa. 2276084 / 8605018142 Bardez 21 42 Sol 7 B Hotel Samrat Shri Victor Fernandes, Dr. Dada Vaidya Road, Panaji- 9860057674 Tiswadi 49 98 Goa. 8 B Hotel Aroma Rua Cunha Rivara Road, Opp. Municipal Garden, 9823021445 Tiswadi 28 56 Panaji-Tiswadi - Goa. 9 B Hotel Sona Rua De Ourem, Near Old Patto Bridge, Panaji-Goa. 9822149848 Tiswadi 26 60 10 B Prainha Resort Near State Bank of India, Dona Paula, Panaji - Goa. 2453881/82 / 83 / Tiswadi 45 90 by the Sea 9822187294 11 B O Pescador Near Dona Paula Jetty, Dona Paula, Panaji, Tiswadi - 7755940102 Tiswadi 20 40 Dona Paula Goa. Beach Resort 12 B Hotel Goa Near Miramar Beach, Tonca, Panaji-Goa. 9821016029 Tiswadi 35 70 International 13 B Hotel Satya Near Maruti Temple, Mapusa, Bardez, Goa 9822103529 Bardez 34 68 Heera 14 B Holiday Beach Candolim, Bardez, Goa 9822100517 / 2489088 Bardez 20 40 Resort / 2489188 15 B Mapusa Mapusa, Bardez - Goa 2262794 / 2262694 / Bardez 48 104 Residency 9403272165 16 B Panaji Residency Near Old Secretariat, Opp. -

The Tradition of Serpent Worship in Goa: a Critical Study Sandip A

THE TRADITION OF SERPENT WORSHIP IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY SANDIP A. MAJIK Research Student, Department of History, Goa University, Goa 403206 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: As in many other States of India, the State of Goa has a strong tradition of serpent cult from the ancient period. Influence of Naga people brought rich tradition of serpent worship in Goa. In the course of time, there was gradual change in iconography of serpent deities and pattern of their worship. There exist a few writings on serpent worship in Goa. However there is much scope to research further using recent evidences and field work. This is an attempt to analyse the tradition of serpent worship from a historical and analytical perspective. Keywords: Nagas, Tradition, Sculpture, Inscription The Ancient World The Sanskrit word naga is actually derived from the word naga, meaning mountain. Since all the Animal worship is very common in the religious history Dravidian tribes trace their origin from mountains, it of the ancient world. One of the earliest stages of the may probably be presumed that those who lived in such growth of religious ideas and cult was when human places came to be called Nagas.6 The worship of serpent beings conceived of the animal world as superior to deities in India appears to have come from the Austric them. This was due to obvious deficiency of human world.7 beings in the earliest stages of civilisation. Man not equipped with scientific knowledge was weaker than the During the historical migration of the forebears of animal world and attributed the spirit of the divine to it, the modern Dravidians to India, the separation of the giving rise to various forms of animal worship. -

SR.No. Route ROUTES OPERATED by KTCL

ROUTES OPERATED BY KTCL SR.No. Route 1 Panaji-Mapusa-Sankhali-Valpoi-Dhave-Uste 2 Agapur-Borim-Verna Industy-Vasco 3 Amthane-Pirna-Revoda-Mapusa-Panaji 4 Badami-Belgavi-Bicholim-Panaji 5 Bamboli-Marcel-Valpoi-Signe 6 Bhiroda-Sankhali-Marcel-Panaji 7 Bibal-Paz-Cortalim-Panaji 8 Bicholim-Marcel-Mardol-Ponda 9 Bicholim-MayemLake-Aldona-Mapusa 10 Bicholim-Pilgao-Saptakoteshwar-Narva 11 Bicholim-Poira-Sinquerim-Bicholim 12 Bicholim-Sarmans-Pilgao-Narva 13 Bicholim-Tikhajan-Kerem-Madel 14 Canacona-Palolem-Cab de Ram 15 Canacona-Val-Khangini-Balli-Margao 16 Cuncolim-Vellim 17 Curchorem-Farmagudi 18 Curchorem-Rivona-Vadem 19 Curchorem-Sanguem-Tudva-Verlem 20 Dabe-Mopirla-Fatorpa-Cuncolim-Margao-Panaji 21 Dhada-Maingine-Ponda-Farmagudi 22 Harmal-Mandre-Siolim-Mapusa 23 Ibrampur-Assonora-Bicholim-Advoi-Valpoi 24 Juvem-Kumbharjua-Marcel-Betki-Savoi-Bhatle 25 Kawar-Canacona-Rajbag 26 Mapusa-Aldona-Khorjuve-Goljuve 27 Mapusa-Aldona-Madel 28 Mapusa-Aldona-Poira-Bicholim 29 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Korgao 30 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Sawantwada-Mandre 31 Mapusa-Azilo District Hospital 32 Mapusa-Bastora-Chandanwadi 33 Mapusa-Bicholim-Poira 34 Mapusa-Bicholim-Sankhali-Valpoi-Hivre 35 Mapusa-Calvi-Madel 36 Mapusa-Carona-Amadi 37 Mapusa-Colvale-Dadachiwadi-Madkai 38 Mapusa-Duler-Camurli 39 Mapusa-Karurli-Aldona-Pomburpa-Panaji 40 Mapusa-Khorjuve-Bicholim-Varpal 41 Mapusa-Marna-Siolim 42 Mapusa-Nachnola-Carona-Calvi 43 Mapusa-Palye-Succuro-Bitona-Panaji 44 Mapusa-Panaji-Fatorpha(Sunday) 45 Mapusa-Pedne-Pednekarwada-Mopa 46 Mapusa-Saligao-Calangute-Pilerne-Panaji 47 Mapusa-Siolim -

GOA and PORTUGAL History and Development

XCHR Studies Series No. 10 GOA AND PORTUGAL History and Development Edited by Charles J. Borges Director, Xavier Centre of Historical Research Oscar G. Pereira Director, Centro Portugues de Col6nia, Univ. of Cologne Hannes Stubbe Professor, Psychologisches Institut, Univ. of Cologne CONCEPT PUBLISHING COMPANY, NEW DELHI-110059 ISBN 81-7022-867-0 First Published 2000 O Xavier Centre of Historical Research Printed and Published by Ashok Kumar Mittal Concept Publishing Company A/15-16, Commercial Block, Mohan. Garden New Delhi-110059 (India) Phones: 5648039, 5649024 Fax: 09H 11 >-5648053 Email: [email protected] 4 Trade in Goa during the 19th Century with Special Reference to Colonial Kanara N . S hyam B hat From the arrival of the Portuguese to the end of the 18Ih century, the economic history of Portuguese Goa is well examined by historians. But not many works are available on the economic history of Goa during the 19lh and 20lh centuries, which witnessed considerable decline in the Portuguese trade in India. This, being a desideratum, it is not surprising to note that a study of the visible trade links between Portuguese Goa and the coastal regions of Karnataka1 is not given serious attention by historians so far. Therefore, this is an attempt to analyse the trade connections between Portuguese Goa and colonial Kanara in the 19lh century.2 The present exposition is mainly based on the administrative records of the English East India Company government such as Proceedings of the Madras Board of Revenue, Proceedings of the Madras Sea Customs Department, Madras Commercial Consultations, and official letters of the Collectors of Kanara.