“Service Innovation: Managing Innovation from Idea Generation to Innovative Offer”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRAND NAME PRODUCTS Branded Male Marketing to Men.Pdf

Branded Male hb aw:Branded Male 15/1/08 10:10 Page 1 BRANDED MALE Mark Tungate is the “Tungate dissects the social trends that have been shaping the male consumer across a Men are not what they were. In article after author of the variety of sectors in recent years… Provides insights on how brands can tackle the article we’re told a new type of man is bestselling Fashion business of engaging men in a relevant way – and the influential role that the women in abroad – he’s more interested in looking Brands, as well as the their lives play.” good and he’s a lot keener on shopping. highly acclaimed Carisa Bianchi, President, TBWA / Chiat / Day, Los Angeles Adland: A Global Branded Male sets out to discover what History of Advertising, “Finally a book that uses humour, examples and clever storytelling to shed a new light on makes men tick as consumers and how both published by male trends. Helps us approach male consumers as human beings and not simply as products and services are effectively Kogan Page. Based in marketing targets.” branded for the male market. Using a day Photography: Philippe Lemaire Paris, he is a journalist in the life of a fictional “branded male”, specializing in media, marketing and Roberto Passariello, Marketing Director, Eurosport International Mark Tungate looks at communication. Mark has a weekly column BRANDED male-orientated brands and their in the French media magazine Stratégies, “Ideas, advice and insights that will help anyone aiming to get messages across marketing strategies in areas as diverse as: and writes regularly about advertising, style to men.” and popular culture for the trends David Wilkins, Special Projects Officer, Men’s Health Forum • grooming and skincare; intelligence service WGSN and the • clothes; magazine Campaign. -

Keeper of the City's Treasures

SPRING 2020 A HIVE OF INDUSTRY Museum of Making gets ready for autumn opening THRILLS AND SKILLS The team designing the world’s top theme parks KEEPER OF THE CITY’S TREASURES Old Bell saviour’s rescue plan for world-famous store CELEBRATING THE CREATIVITY AND SUCCESS OF BUSINESSES IN DERBY AND DERBYSHIRE IT’S A FACT DID YOU KNOW THAT 11.8% WELCOME TO INNOVATE - A WINDOW INTO THE AMAZING AND INSPIRING DERBY OF DERBY’S WORKFORCE AND DERBYSHIRE BUSINESS SECTOR. BROUGHT TO YOU BY MARKETING DERBY, ARE IN HIGH-TECH ROLES? INNOVATE WILL SHOWCASE THE WORK OF BRILLIANT BONDHOLDERS AND LOCAL THAT’S 4X THE COMPANIES AND PROFILE THE TALENTED INDIVIDUALS LEADING THEM. ENJOY! NATIONAL AVERAGE. 2 SPRING 2020 3 CONTENTS 16 CONTRIBUTORS Star performers! How some of the world's biggest music stars are helping Derbyshire achieve cricketing success. Steve Hall Writing and editing: Steve Hall has worked in the media for more than 35 years and is a former Editor and Managing Director of the Derby Telegraph. He has won numerous industry awards, including UK 06 24 Newspaper of the Year Safe in his hands Riding high! and UK Editor of the Year. Paul Hurst has already rescued The creative business that He now runs his own the historic Old Bell Hotel - now theme parks all over the media consultancy. he's bringing back the world's globe are turning to for oldest department store. thrills and skills. 52Silk Mill - a glimpse behind the scenes 40 48 50 Andy Gilmore We take a look at progress as Derby's impressive new Breathing new life £200 million scheme Shaping up Museum of Making shapes up for its September opening. -

Leisure and Tourism Sector Review

JUNE 2020 Leisure and Tourism Sector Review 01872 229 000 www.atlanticmarkets.co.uk www.atlanticmarkets.co.uk The recent market collapse has weighed heavily on certain sectors more than others, undoubtedly one of the biggest casualties is those relating to travel, leisure and tourism. Whilst some sectors are now in full swing recovery, the travel stocks are still bumping along lows with sporadic moves up and down in the short term as the market wrestles with short term impact Vs long term prospects. As we see global economies ease lockdowns and talk emerges of international travel starting again, all eyes turn to the sector and the potential for recovery. The firms involved will be sure the recovery is on as we come out of lockdowns but that is only one issue for them, they also need to rebuild consumer confidence. Air travel, cruise ships, and package holidays could be a tough sell this summer. Social distancing rules and the threat of quarantining mean popular holiday activities will be more restricted than usual. Tui Travel Ticker: TUI 6 month high: 979p Brief History TUI Travel PLC is a British leisure travel group headquartered in Crawley, West Sussex. The company was formed in September 2007 by the merger of First Choice Holidays PLC and the Tourism Division of TUI AG. The company was originally founded in 1923 in Berlin. In 2000 it acquired Thomson Travel and in 2002 bought Hapag Lloyd, which itself owned the travel firm TUI (formerly Touristik Union International) and renamed itself TUI AG. In June 2014 TUI AG and TUI Travel announced the two companies would be merged. -

2019 Annual Report and Accounts (Which Control Over the Financial Reporting of the Group

resilient focused data driven ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019 Who we are easyJet makes travel easy, enjoyable and affordable for customers, whether it is for leisure or business. We use our cost advantage and leading positions in primary airports to deliver low fares and operational efficiency, seamlessly connecting Europe with the warmest welcome in the sky. Our well-established business model provides a strong foundation to drive profitable growth and long-term shareholder returns. We are proud to have been awarded Best Low-Cost Airline in Europe at the Skytrax World Airlines Awards 2019. ‘Our Promise’ is that we will be: SAFE AND ON OUR IN IT ALWAYS FORWARD RESPONSIBLE CUSTOMERS’ TOGETHER EFFICIENT THINKING SIDE PAGE CONTENTS our value STRATEGIC REPORT 2 At a glance creation 3 Chairman’s letter 10 Highlights framework 12 Business model 14 Market review The foundation 15 Stakeholder engagement for who we are 2 16 Chief Executive’s review and what we do and Our Strategy 26 Key performance indicators 28 Financial review 35 Viability statement 36 Summary statistics 37 Risk PAGE 48 Sustainability our performance CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 66 Chairman’s statement Key highlights on corporate governance of the year’s 68 Board of Directors performance 10 72 Airline Management Board 75 Corporate governance report 96 Directors’ remuneration report 116 Directors’ report 120 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities PAGE ACCOUNTS our pLAN 121 Independent auditors’ report to the members of easyJet plc The strategic plan which 128 Consolidated accounts we announced last year 133 Notes to the accounts is now fully embedded 174 Company accounts across easyJet 176 Notes to the Company accounts 16 179 Five-year summary 180 Glossary 181 Shareholder information our commitment PAGE Sustainability is a key part of Our Promise 48 VISIT OUR WEBSITE FOR MORE INVESTOR INFORMATION corporate.easyJet.com/investors www.easyJet.com 1 AT A GLANCE our value creation framework easyJet’s value creation framework is the foundation for who we are and what we do. -

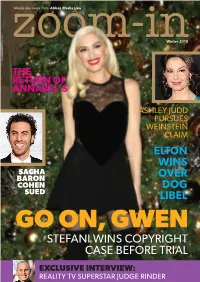

Zoom-In Issue 12

Media law news from Abbas Media Law zoom-inWinter 2018 THE RETURN OF ANNABEL’S ASHLEY JUDD PURSUES WEINSTEIN CLAIM ELTON WINS SACHA BARON OVER COHEN DOG SUED LIBEL GO ON, GWEN STEFANI WINS COPYRIGHT CASE BEFORE TRIAL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: REALITY TV SUPERSTAR JUDGE RINDER IN THIS ISSUE Geoffrey Rush gives evidence .........14 20 QUESTIONS Labour chief whip settles libel claim .14 Rob Rinder on how he brought his legal skills to TV ............................ 22 Mirror fails to strike out claim ..........15 Public interest defence wins on appeal .15 BUSINESS AFFAIRS & RIGHTS Abbas Media Law’s production legal schedule, setting out the five key stages of TV production and the legal issues producers must consider. In this issue, we focus on ‘fixer’ agreements ....... 16 COPYRIGHT & IP RIGHTS Rod Stewart sued over photo of WINNERS & LOSERS himself .........................................18 No trial for Stefani and Williams ........ 4 EU approves controversial directive .18 MEDIA HAUNTS Rebel Wilson damages appeal fails ... 4 It used to be THE place in London – is Netflix facing claim over Easy .........19 fabulous nightclub Annabel’s now back Payout for Elton John ...................... 4 New trial in Stairway to Heaven case ..20 on top? ...................................... 24 Property developer gets libel payout ... 6 Tracy Chapman sues Nicki Minaj ..... 20 Setback for Kendrick Lamar in video PRIVACY & DATA PROTECTION REGULATION – OFCOM, battle ..........................................21 Morrisons liable for data breach ..... 26 ASA & -

The Easygroup Brand Manual

what makes us tick? section 1 our identity section 2 brand application The easyGroup Brand Manual © copyright easyGroup IP Licensing Ltd. p1 1 /36 section 3 last revised: AprApril 2011 2005 Hi from Stelios Dear friends and colleagues, The ’easy’ brand, which I started with the launch of the of the younger businesses have articulated, to some airline in 1995, is now used by more than a dozen degree, their own values. However this manual is for the different businesses and millions of consumers from all entire ’easy’ brand and it identifies the common themes over the world. I believe it is an extremely valuable asset amongst all the ’easy’ businesses. which can generate substantial success for all involved with it. A brand is always evolving and people’s perceptions of it do change from time to time. However I still believe Therefore we have created this brand manual. Like any that there are eight values (listed on p14) that all ’easy’ manual, its objective is to help people who use the businesses share and sticking to them is a good idea for brand to understand its origin, the brand values and the everybody. Remember there is strength in unity. best ways of getting the most out of it. I want you, as a partner or associate to get close to our This brand manual is written for the benefit of those way! How we do business, how we communicate, what people within the easyGroup, or franchisees or we believe in and ultimately where we are going. licensees of the ’easy’ brand and for those who are considering buying into the brand. -

Cruising with Holland America Line Tourism, Corporate Identity and Corporate History

1 Cruising with Holland America Line Tourism, corporate identity and corporate history Ferry de Goey Faculty of History and Arts Erasmus University Rotterdam The Netherlands [email protected] Paper for the EBHA Conference 2005 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany (September 1 - 3, 2005) Session 2 C: Images of Transport Do not quote without permission. © Ferry de Goey (2005) 2 “The reason for our success is that we meet and exceed the expectations of our guests every day; we create dr eams for them every day. There is no better value.” (Micky Arison, Chairman and CEO Carnival Corporation, 2004) If you remember Captain Stubing, cruise director Julie McCoy, bartender Isaac Washington, and yeoman-purser “Gopher” Smith of the 1970s television series The Love Boat, you probably have the right age to take a cruise.1 You shall not be alone; in 2005, about 11.1 million people will join you on a cruise. Economic research documents the tremendous growth of tourism in general and particularly the cruise industry after the 1960s. Worldwide employment in tourism in 2001 was 207 million jobs or 8 percent of all jobs. About 11 percent (or 3.3 trillion US Dollars) of global GDP is contributed by the tourist industry and some 698 million tourists generated this economic result. While tourism used to be located in Europe and the USA (in 1950 the top 15 tourist attractions were all located in Europe and the USA), today tourism is a global industry with multinational enterprises.2 Tourism is an exceptionally dynamic industry with businesses constantly inventing new attractions. -

Trade Marks and Brands

This page intentionally left blank Trade Marks and Brands Recent developments in trade mark law have called into question a variety of basic features, as well as bolder extensions, of legal protection. Other disciplines can help us think about fundamental issues such as: What is a trade mark? What does it do? What should be the scope of its protection? This volume assembles essays examining trade marks and brands from a multiplicity of fields: from business history, marketing, linguistics, legal history, philosophy, sociology and geography. Each part pairs lawyers’ and non-lawyers’ perspectives, so that each commentator addresses and critiques his or her counterpart’s analysis. The perspec- tives of non-legal fields are intended to enrich legal academics’ and practitioners’ reflections about trade marks, and to expose lawyers, judges and policy-makers to ideas, concepts and methods that could prove to be of particular importance in the development of positive law. LIONEL BENTLY is Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law at the University of Cambridge, Director of the Centre for Intel- lectual Property and Information Law at the University of Cambridge, and a Professorial Fellow at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. JENNIFER DAVIS is Newton Trust Lecturer and Fellow of Wolfson College, University of Cambridge. JANE C. GINSBURG is the Morton L. Janklow Professor of Literary and Artistic Property Law at Columbia University School of Law. She also directs the law school’s Kernochan Center for Law, Media and the Arts. Cambridge Intellectual Property and Information Law As its economic potential has rapidly expanded, intellectual property has become a subject of front-rank legal importance. -

Practicing What You Preach

Business GDPR Tackling Advice Update Online for Lawyers Threats page 7 page 8 page 17 141st Annual Meeting, Boston daily news Wednesday May 22, 2019 Practicing What You Preach Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become an important issue for brands, but it’s vital to back up your good words with good actions, as Rory O’Neill reports. limate change has the potential to however, do so at their own peril, Cbe the defining social and political and often at significant risk to their issue of our era. As calls increase for brand. This was the warning from governments to declare a climate the panel at yesterday’s session Natasha Reed highlights “green trademarks.” emergency, there has never been more CT03 Brand Protection and the scrutiny on what decision makers, Intersection of Trademarks, John F. Kennedy School of Government LLP (USA), described them. Companies whether in the political or corporate Advertising, and Corporate Social at Harvard University (USA): “CSR may choose a green trademark to sphere, are doing to tackle the problem. Responsibility, which discussed the encompasses not only what companies define not just a single product line as It is little surprise, then, that brands branding implications of corporate do with their profits, but also how they eco-friendly, but possibly their whole are increasingly attempting to define social responsibility (CSR). make them.” brand identity. themselves as “green” in an effort to As Gare Smith, Partner, Corporate The increased focus on CSR, both Failure to get it right, however, can make it known that they are part of the Social Responsibility Practice, Foley from consumers and in the media, has cause reputational damage, Ms. -

New Growth with Second Stand Area

Rendering: Meplan München. Halle A 2 Stand A2.140 THE PARTNERS OF THE „WORLD OF HOSPITALITY“ 2019 und A2.040 New growth 10 with second stand area For years there has been a desire for place larger individual stands on an profiles of all co-exhibitors to quickly larger and individually designed exhibi- additional stand space next to the main find the right contacts among the 29 tor areas under the umbrella of the stand. exhibiting companies from hotel opera- „World of Hospitality“ (WoH). Last year In order to master the logistical chal- tions, investment, project development Letomotel had already taken advantage lenges during trade fair operations, the and consulting. of this opportunity and very successfully number of service staff was increased Expo Real visitors can look forward implemented an individual corner stand once again and a second fully to an efficiently organised „World of solution. With AccorInvest and the equipped kitchen was installed on the Hospitality“ again this year with a wide GSH/Gorgeous Smiling Hotels it has new stand. At the WoH reception, visi- range of expertise in all aspects of hotel now been possible for the first time to tors will find a compact guide with brief real estate. The 29 exhibitors at a glance: • AccorInvest • Engel & Völkers Hotel Consulting • King‘s Hotels • Achat Hotels • GSH – Gorgeous Smiling Hotels • LetoMotel • Aroundtown SA • HCS-Solutions GmbH • LFPI Hotels Deutschland • barefoot Hotels • Hofer Land – Fichtelgebirge – • Plaza Hotelgroup • Choice Hotels Region Bayreuth • prizeotel Hotel -

2019 Annual Report and Accounts

easyHotel NEVER FAR plc FROM THE | Annual report and accounts 2019 Annual report ACTION easyHotel plc Annual report and accounts 2019 Our journey easyHotel is an AIM-listed super budget hotel chain. Contents Founded in 2004 by Sir Stelios Haji-Ioannou, easyHotel Strategic report was established on the core principle that travel should IFC Our journey be for the many, not the few. 1 Highlights The business was admitted to the London Alternative Investment 2 easyHotel at a glance 3 Chief Executive Officer’s review Market in June 2014. In recent years the brand has built 6 Chief Financial Officer’s review significant momentum against its ambitious growth strategy, 8 Risk management and principal risks with a strong development pipeline across key international Governance cities and a busy opening programme. 10 Chairman’s corporate governance statement Today, the easyHotel network includes 40 hotels, covering 12 Audit committee report 13 Directors’ report 32 towns and cities and 13 countries. Every one of our hotels is 14 Remuneration report based in a prime location – a great base offering great value and fulfilling our mission of making “being there possible for everyone”. Financial statements 15 Independent auditors’ report easyHotel is for people who believe that life is for living. 18 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income The type of person who wants to make the most of every 19 Consolidated statement moment. We make it simple for our customers to do what of financial position they want to do, when they want to do it, whether that’s 20 Consolidated statement exploring a city on a mini-break, going to a cup final, seeing of cash flows 21 Consolidated statement their favourite band, spending time with friends and family, of changes in equity getting to an important business meeting, or just chillaxing! 22 Company statement of financial position Our business model may be simple, but we are relentlessly 23 Company statement innovative and ambitious. -

Printmgr File

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you are recommended to seek your own personal financial advice from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other financial adviser authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. If you have sold or otherwise transferred all your Shares in easyJet plc, please send this document, together with the accompanying Form of Proxy, as soon as possible to the purchaser or transferee, or to the stockbroker, bank or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected, for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. Credit Suisse, which is regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Services Authority, is acting for easyJet plc and no-one else in connection with the Proposed Transaction and will not be responsible to anyone other than easyJet plc for providing the protections afforded to clients of Credit Suisse or for providing advice in relation to the Proposed Transaction. easyJet plc (Incorporated and registered in England and Wales under the Companies Act 1985 with registered number 3959649) Proposed resolution of Brand Licence Dispute and Notice of Extraordinary General Meeting This document should be read as a whole. Your attention is drawn to the letter from your Chairman which is set out on pages 3 to 8 of this document and which recommends you vote in favour of the resolutions to be proposed at the Extraordinary General Meeting referred to below. Notice of an Extraordinary General Meeting of easyJet plc to be held at 9:30 am on 10 December 2010 at Hangar 89, London Luton Airport, Luton, Bedfordshire LU2 9PF is set out at the end of this document.