World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politik Dimalaysia Cidaip Banyak, Dan Disini Sangkat Empat Partai Politik

122 mUah Vol. 1, No.I Agustus 2001 POLITICO-ISLAMIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA IN 1999 By;Ibrahim Abu Bakar Abstrak Tulisan ini merupakan kajian singkat seJdtar isu politik Islam di Malaysia tahun 1999. Pada Nopember 1999, Malaysia menyelenggarakan pemilihan Federal dan Negara Bagian yang ke-10. Titik berat tulisan ini ada pada beberapa isupolitik Islamyang dipublikasikandi koran-koran Malaysia yang dilihat dari perspektifpartai-partaipolitik serta para pendukmgnya. Partai politik diMalaysia cidaip banyak, dan disini Sangkat empat partai politik yaitu: Organisasi Nasional Malaysia Bersatu (UMNO), Asosiasi Cina Ma laysia (MCA), Partai Islam Se-Malaysia (PMIP atau PAS) dan Partai Aksi Demokratis (DAP). UMNO dan MCA adalah partai yang berperan dalam Barisan Nasional (BA) atau FromNasional (NF). PASdan DAP adalah partai oposisipadaBarisanAltematif(BA) atau FromAltemattf(AF). PAS, UMNO, DAP dan MCA memilikipandangan tersendiri temang isu-isu politik Islam. Adanya isu-isu politik Islam itu pada dasamya tidak bisa dilepaskan dari latar belakang sosio-religius dan historis politik masyarakat Malaysia. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^^ ^ <•'«oJla 1^*- 4 ^ AjtLtiLl jS"y Smi]?jJI 1.^1 j yLl J J ,5j^I 'jiil tJ Vjillli J 01^. -71 i- -L-Jl cyUiLLl ^ JS3 i^LwSr1/i VjJ V^j' 0' V oljjlj-l PoUtico-Islnndc Issues bi Malays bi 1999 123 A. Preface This paper is a short discussion on politico-Islamic issues in Malaysia in 1999. In November 1999 Malaysia held her tenth federal and state elections. The paper focuses on some of the politico-Islamic issues which were pub lished in the Malaysian newsp^>ers from the perspectives of the political parties and their leaders or supporters. -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Racialdiscriminationreport We

TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Definition of Racial Discrimination......................................................................................................................... 4 Racial Discrimination in Malaysia Today................................................................................................................. 5 Efforts to Promote National Unity in Malaysia in 2018................................................................................... 6 Incidences of Racial Discrimination in Malaysia in 2018 1. Racial Politics and Race-based Party Politics........................................................................................ 16 2. Groups, Agencies and Individuals that use Provocative Racial and Religious Sentiments.. 21 3. Racism in the Education Sector................................................................................................................. 24 4. Racial Discrimination in Other Sectors................................................................................................... 25 5. Racism in social media among Malaysians........................................................................................... 26 6. Xenophobic -

Carroll Round Proceedings

Carroll Round Proceedings Carroll Fourth Annual Carroll Round Volume I Volume 1Volume 2006 Carroll Round Proceedings Georgetown University The Carroll Round at Georgetown University Box 571016 Washington, DC 20057 Tel: (202) 687-8488 Fax: (202) 687-1431 [email protected] http://carrollround.georgetown.edu The Fifth Annual Carroll Round Steering Committee Irmak Bademli Stephen A. Brinkmann Héber M. Delgado-Medrano Lucia Franzese Yasmine N. Fulena Jennifer J. Hardy Michael K. Kunkel Marina Lafferriere, Chair Yousif H. Mohammed Maira E. Reimão Tamar L. Tashjian Carroll Round Proceedings Copyright © 2006 The Carroll Round Georgetown University Washington, DC http://carrollround.georgetown.edu All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or an information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the contribut- ing authors. The Carroll Round reserves the copyright to the Carroll Round Proceedings volumes. Original works included in this volume are printed by consent of the respective authors as established in the “Non-Exclusive Copyright Agreement.” The Carroll Round has received permission to copy, display, and distribute copies of the contributors’ works through the Carroll Round website (carrollround.georgetown.edu) and through the annual proceedings publication. The contributing authors, however, retain the copyright and all other rights including, without limitation, the right to copy, distribute, publish, display, or modify the copyright work, and to transfer, assign, or grant license of any such rights. Printed in the United States of America. CARROLL ROUND PROCEEDINGS The Fourth Annual Carroll Round An Undergraduate Conference Focusing on Contemporary International Economics Research and Policy VOLUME I Editor-in-Chief: Héber M. -

Idss Commentaries

RSIS COMMENTARIES RSIS Commentaries are intended to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy relevant background and analysis of contemporary developments. The views of the authors are their own and do not represent the official position of the S.Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced electronically or in print with prior permission from RSIS. Due recognition must be given to the author or authors and RSIS. Please email: [email protected] or call (+65) 6790 6982 to speak to the Editor RSIS Commentaries, Yang Razali Kassim. __________________________________________________________________________________________________ No. 056/2013 dated 8 April 2013 Malaysia’s Mother of All Elections: A Turning Point? By Yang Razali Kassim Synopsis This Malaysian general election will be the most critical battle for power between the ruling coalition and the opposition. Much is at stake: from the future of Malaysian politics to the future of two leaders – Prime Minister Najib Razak and opposition chief Anwar Ibrahim. What will GE13 lead to? Commentary MALAYSIA’S 13th general election will be the most crucial in decades: a titanic battle for the ruling Barisan Nasional to retain power and a referendum on the political future of two leaders. Once close allies in UMNO, Prime Minister Najib Razak and his challenger, opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, a former UMNO deputy president and deputy prime minister, will clash directly for the first time in an electoral test of wills and skills. Who between them will go on to lead the country, and who will be consigned to history will be known only after the 13th general election is fought and concluded in the coming weeks. -

Ex-Pas Candidate to Make Defence in Sarong Lifting Case (NST 10/05/2004)

10/05/2004 Ex-Pas candidate to make defence in sarong lifting case ALOR STAR, Sun. - A former Pas election candidate who allegedly lifted his sarong and exposed his genitals to a Puteri Umno member has to make his defence in court. The High Court set aside a lower court's decision to acquit Abdul Razak Abas, saying that a prima facie case had been made against Razak. Judge Zainal Adzam Abdul Ghani ordered the case to be sent back to a magistrate's court. He said that he would issue his judgment later. Razak, 57, gained notoriety in the run-up to the Anak Bukit by-election in July 2002 when he was accused of lifting his sarong and exposing his genitals to Yusnita Romli. In December 2002, magistrate Mohd Redzuan Abdullah acquitted Razak without calling for his defence, saying that the prosecution had failed to prove a reasonable case. If convicted, he faces a jail term of up to five years, a fine or both. Razak stood as a candidate in the 1999 general election, contesting in Gua Musang under the Pas ticket but lost to Barisan Nasional candidate Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah by 2,295 votes. At today's hearing, Zainal also turned down the defence's application to issue a contempt of court order against Puteri Umno chief Datuk Azalina Othman Said and four others for making statements on the case while the appeal hearing was still underway. The four are former Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad; Prime Minister Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi who was then Deputy Prime Minister; Culture, Arts and Heritage Minister Datuk Seri Dr Rais Yatim who was then Minister in the Prime Minister's Department and Kelantan Umno chief Datuk Mustapha Mohamad. -

201014Anwartimeline Copy2

Anwar’s gambit Malaysia saw a drama-lled day yesterday as opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, in his gambit for power, had an audience with the King, Sultan Abdullah Ri’ayatuddin. Mr Anwar with Here is the timeline the King at the of events. royal palace in Kuala Lumpur Datuk Seri Anwar leaving the royal palace (above and left) after meeting the King. yesterday. 8am 9 10 11 12 1pm 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11pm 8am 10.25am 11.30am 2pm 2.30pm 5pm Around 7pm 11pm • Cameramen, videographers and • Datuk Seri • He leaves the palace • Mr Anwar holds a news conference at Le Meridien hotel. • The palace issues a statement • Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin holds • Former premier Mahathir • Umno issues statement that it reporters start to gather. Dozens of Anwar arrives after meeting the King, He claims he has 120 MPs on his side and that the King has saying Mr Anwar presented to a Facebook Live session for an hour with Mohamad says in a might consider pulling out of journalists receive McDonald’s treats in a black car. without speaking to been given “documents” to back up his assertion. the King the number of MPs local media, saying he wants to focus on one-minute video that he is ruling alliance Perikatan Nasional, from the King through his private the media. • Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, 83, chairman of Umno’s supporting him, but did not ghting Covid-19 and the struggling not endorsing any individual unless it gets new terms of secretary outside the palace gates. -

Coup Brewing in Kelantan Umno (HL) (NST 29/03/2002)

29/03/2002 Coup brewing in Kelantan Umno (HL) Shamsul Akmar KUALA LUMPUR, Thurs. - A classic Kelantan Umno political wayang kulit is unfurling as 12 of the 14 division heads seek to replace the party's State office bearers. On March 16, barely hours after attending a State Umno liaison meeting, the 12 division heads gathered for dinner at the residence of a colleague from southern Kelantan. Sources revealed that they collectively agreed the office bearers were ineffective. The office bearers are chairman Datuk Mustapa Mohamed, secretary Datuk Ahmad Rusli Ibrahim, treasurer Datuk Dr Nik Hussain Abdul Rahman, information chief Mohd Noor Deris and executive secretary Mohd Nawawi Yaacob. The 12 division heads' stand is that as long as the current office bearers held their positions, Kelantan Umno would not be able to make a dent on Pas' grip on the State, which is going into its 12th year. It was learnt, with the exception of Mustapa, who is Jeli division head, and Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah of Gua Musang, all the other 12 division heads and the Kelantan Wanita Umno chief were present at the gathering. A division head who was present tried to downplay the meeting. "It was a dinner in which we came separately. Some left earlier than the others. Never at any one time were all 12 of us present," he said on condition of anonynmity. He, however, confirmed that there was a consensus among all the 12 present that the five office bearers needed to be replaced. Another division head who was present also confirmed the stand but insisted that it was not an attempt to create a coup. -

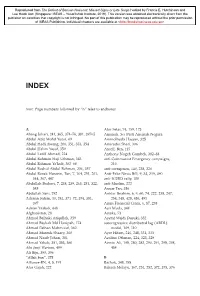

Page Numbers Followed by “N” Refer to Endnotes. a Abang Johari, 241, 365

INDEX Note: Page numbers followed by “n” refer to endnotes. A Alor Setar, 74, 159, 173 Abang Johari, 241, 365, 374–76, 381, 397n5 Amanah. See Parti Amanah Negara Abdul Aziz Mohd Yusof, 69 Aminolhuda Hassan, 325 Abdul Hadi Awang, 206, 351, 353, 354 Amirudin Shari, 306 Abdul Halim Yusof, 359 Ansell, Ben, 115 Abdul Latiff Ahmad, 224 Anthony Nogeh Gumbek, 382–83 Abdul Rahman Haji Uthman, 343 anti-Communist Emergency campaigns, Abdul Rahman Ya’kub, 367–68 210 Abdul Rashid Abdul Rahman, 356, 357 anti-corruption, 140, 238, 326 Abdul Razak Hussein, Tun, 7, 164, 251, 261, Anti-Fake News Bill, 9, 34, 319, 490 344, 367, 447 anti-ICERD rally, 180 Abdullah Badawi, 7, 238, 239, 263, 281, 322, anti-Muslim, 222 348 Anuar Tan, 356 Abdullah Sani, 292 Anwar Ibrahim, 6, 9, 60, 74, 222, 238, 247, Adenan Satem, 10, 241, 371–72, 374, 381, 254, 348, 428, 486, 491 397 Asian Financial Crisis, 6, 87, 238 Adnan Yaakob, 448 Asri Muda, 344 Afghanistan, 28 Astaka, 73 Ahmad Baihaki Atiqullah, 359 Asyraf Wajdi Dusuki, 352 Ahmad Bashah Md Hanipah, 174 autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) Ahmad Fathan Mahmood, 360 model, 109, 110 Ahmad Marzuk Shaary, 360 Ayer Hitam, 246, 248, 331, 333 Ahmad Nazib Johari, 381 Azalina Othman, 224, 323, 329 Ahmad Yakob, 351, 353, 360 Azmin Ali, 195, 280, 283, 290, 291, 295, 298, Aku Janji Warisan, 409 454 Ali Biju, 390, 396 “Allah ban”, 375 B Alliance-BN, 4, 5, 191 Bachok, 348, 355 Alor Gajah, 222 Bahasa Melayu, 167, 251, 252, 372, 375, 376 19-J06064 24 The Defeat of Barisan Nasional.indd 493 28/11/19 11:31 AM 494 Index Bakun Dam, 375, 381 parliamentary seats, 115, 116 Balakong, 296, 305 police and military votes, 74 Balakrishna, Jay, 267 redelineation exercise, 49, 61, 285–90 Bandar Kuching, 59, 379–81, 390 in Sabah, 402, 403 Bangi, 69, 296 in Sarawak, 238, 246, 364, 374–78 Bangsa Johor, 439–41 Sarawak BN. -

50 Reasons Why Anwar Cannot Be Prime Minister 287–8, 298 Abdul

Index 50 Reasons Why Anwar Cannot be mega-projects 194, 313–14, Prime Minister 287–8, 298 320–1, 323 successor 126, 194, 307–9, 345 Abdul Aziz Shamsuddin 298 Proton 319–21 Abdul Aziz Taha 158 Abdullah Majid 35, 36 Abdul Daim Zainuddin see Daim Abdullah Mohamed Yusof 133 Zainuddin Abu Bakar Ba’asyir 228–9 Abdul Gani Patail see Gani Patail Abu Sahid Mohamed 176 Abdul Ghafar Baba see Ghafar Baba affirmative action programme (New Abdul Khalid Sahan 165 Economic Policy/NEP) 30–1, 86, Abdul Qadeer Khan 313 87, 88–9, 96, 98, 101, 103–4, Abdul Rahim Aki 151, 152 110–13, 142, 155, 200, 230, 328, Abdul Rahim Bakar 201 329, 348 Abdul Rahim Noor see Rahim Noor Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Abdul Rahman Putra see Tunku Abdul Organization 23 Rahman agriculture 88–9, 104, 111 Abdul Rahman Aziz 227 Ahmad Zahid Hamidi see Zahid Hamidi Abdul Razak Hussein see Razak Ali Abul Hassan Sulaiman 301 Hussein Aliran (multiracial reform movement) Abdul Wahab Patail see Wahab Patail 66, 70, 324, 329 Abdullah Ahmad 4, 26, 27, 32, 35–6, Alliance 17 38, 128, 308, 319 government 18–19, 24–5, 53, 126, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi see Abdullah 218 Badawi see also National Front Abdullah Badawi 235–7, 268, 299 Alor Star 3, 4–5, 11, 14–15, 16, 130 2004 election 317–18 MAHA Clinic (“UMNO Clinic”) 13, anti-corruption agenda 310–12, 191 317–18, 319, 327–8, 330–1 Mahathir Mohamad’s relocation to Anwar Ibrahim case 316 Kuala Lumpur from 31 corruption and nepotism Alternative Front 232, 233 allegations 312–13, 323 Anti-Corruption Agency 90, 282, 301, economic policies 194, 313–14 311, -

Allow Political Ceramahs in Mosques, Says Hadi

19 JUL 1999 Hadi-mosques ALLOW POLITICAL CERAMAHS IN MOSQUES, SAYS HADI KUALA LUMPUR, July 19 (Bernama) -- Political ceramahs which meet Islamic teachings should be allowed in mosques, said PAS deputy president Haji Hadi Awang today. "Politics and religion are inseparable. During the time of Prophet Mohamed, some of his sermons are political ceramahs. Even the sermons by the Caliphs are political in nature and when they were appointed as head of state, they delivered their speeches from the mosque," he told reporters in his office in Parliament House. He was commenting today's newpaper report where former Mufti of the Federal Territory Tan Sri Abdul Kader Talib reminded anti-government khatibs to stop using the mosque as a political platform. Hadi, who is also Terengganu PAS commissioner, said several PAS politicans wanted to give religious talks in mosques but were not allowed. "There seems to be a double standard here. Umno politicians are allowed but not PAS politicians, even when it is on a religious issue," he said. Asked on the chances of the opposition front in winning the the general election, he said it was not impossible but it would not be easy. If the Spirit of Arau, where PAS won the Arau parliamentary by-election, and the uneasiness among the people over the Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim issue persisted, the opposition would have a chance, he said. Asked if the appointment of Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah as Kelantan Umno Chief would erode the people's support to PAS, Hadi said, "The Ku Li factor is no longer a big deal. -

The Unspoken Power: Civil-Military Relations and the Prospects for Reform

THE BROOKINGS PROJECT ON U.S. POLICY TOWARDS THE ISLAMIC WORLD ANALYSIS PAPER ANALYSIS Number 7, September 2004 THE UNSPOKEN POWER: CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS AND THE PROSPECTS FOR REFORM STEVEN A. COOK T HE S ABAN C ENTER FOR M IDDLE E AST P OLICY AT T HE B ROOKINGS I NSTITUTION THE BROOKINGS PROJECT ON U.S. POLICY TOWARDS THE ISLAMIC WORLD ANALYSIS PAPER ANALYSIS Number 7, September 2004 THE UNSPOKEN POWER: CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS AND THE PROSPECTS FOR REFORM STEVEN A. COOK T HE S ABAN C ENTER FOR M IDDLE E AST P OLICY AT T HE B ROOKINGS I NSTITUTION NOTE FROM THE PROJECT CONVENORS The Brookings Project on U.S. Policy Towards the Islamic World is designed to respond to some of the most difficult challenges that the United States will face in the coming years, most particularly how to prosecute the continuing war on global terrorism while still promoting positive relations with Muslim states and communities. A key part of the Project is the production of Analysis Papers that investigate critical, but under-explored, issues in American policy towards the Islamic world. The new U.S. agenda towards the Muslim world claims to be centered on how best it can support change in pre- vailing political structures, as a means towards undercutting the causes of and support for violent radicalism. However, little strategy has been developed for how this U.S. policy of change plans to deal with a key bulwark of the status quo, the present imbalance in civil-military relations in much of the region.