The Portrayal of the Grotesque In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interactive Timeline

http://knowingpoe.thinkport.org/ Interactive Timeline Content Overview This timeline includes six strands: Poe’s Life, Poe’s Literature, World Literature, Maryland History, Baltimore History and American History. Students can choose to look at any or all of these strands as they explore the timeline. You might consider asking students to seek certain items in order to give students a picture of Poe as a writer and the life and times in which he worked. This is not an exhaustive timeline. It simply highlights the major events that happened during Poe’s lifetime. Poe’s Life Edgar Poe is born in Boston on January 19. 1809 Elizabeth Arnold Poe, Poe’s mother, dies on December 8 in Richmond, Virginia. 1811 David Poe, Poe’s mother, apparently dies within a few days. John and Frances Allen adopt the young boy. The Allans baptize Edgar as Edgar Allan Poe on January 7. 1812 Poe begins his schooling 1814 The Allans leave Richmond, bound for England. 1815 Poe goes to boarding school. His teachers refer to him as “Master Allan.” 1816 Poe moves to another English school. 1818 The Allans arrive back in America, stopping for a few days in New York City 1820 before returning to Richmond. Poe continues his schooling. 1821 Poe swims against a heavy tide six or seven miles up the James River. 1824 In November, he also writes a two-line poem. The poem was never published. John Allan inherits a great deal of money and buys a huge mansion in Richmond 1825 for his family to live in. -

Biography of Edgar Allan Poe (Adapted)

Name ________________________________ Date ___________ Period __________ English - Literature Biography of Edgar Allan Poe (Adapted) Poe's Childhood Edgar Poe was born in Boston on January 19, 1809. His parents were David and Elizabeth Poe. David was born in Baltimore on July 18, 1784. Elizabeth Arnold came to the U.S. from England in 1796 and married David Poe after her first husband died in 1805. They had three children, Henry, Edgar, and Rosalie. Elizabeth Poe died in 1811 when Edgar was two years old. She had separated from her husband and had taken her three kids with her. Henry went to live with his grandparents while Edgar was adopted by Mr. and Mrs. John Allan and Rosalie was taken in by another family. John Allan was a successful merchant, so Poe grew up in good surroundings and went to good schools. When Poe was six, he went to school in England for five years. He learned Latin and French, as well as math and history. He later returned to school in America and continued his studies. Edgar Allan Poe went to the University of Virginia in 1826. He was 17. Even though John Allan had plenty of money, he only gave Poe about a third of what he needed. Although Poe had done well in Latin and French, he started to drink heavily and quickly became in debt. He had to quit school less than a year later. Poe in the Army Edgar Allan Poe had no money, no job skills, and had been shunned by John Allan. Therefore, Poe went to Boston and joined the U.S. -

Poe Work Packet

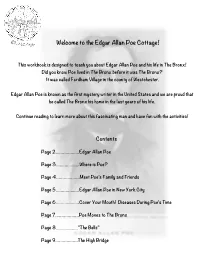

Welcome to the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage! This workbook is designed to teach you about Edgar Allan Poe and his life in The Bronx! Did you know Poe lived in The Bronx before it was The Bronx? It was called Fordham Village in the county of Westchester. Edgar Allan Poe is known as the first mystery writer in the United States and we are proud that he called The Bronx his home in the last years of his life. Continue reading to learn more about this fascinating man and have fun with the activities! Contents Page 2……………….Edgar Allan Poe Page 3……………….Where is Poe? Page 4……………….Meet Poe’s Family and Friends Page 5……………….Edgar Allan Poe in New York City Page 6……………….Cover Your Mouth! Diseases During Poe’s Time Page 7……………….Poe Moves to The Bronx Page 8………………”The Bells” Page 9………………The High Bridge Edgar Poe was born in 1809 in Boston, Massachusetts to actors! He would travel with his mother to shows she performed in. Sadly, she died, but the Allan family took him in and raised him. This is how he took the Allan name. When he grew up he moved around a lot. He lived in Richmond, Virginia, London, England, Baltimore, Maryland, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Boston, Massachusetts, and New York City, New York writing poetry and short stories! He even studied at West Point Military Academy for a time. It was in Baltimore where he met and married his wife Virginia. Virginia and her mother, Maria Clemm, moved to New York City with Edgar. -

AM Edgar Allan Poe Subject Bio & Timeline

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #AmericanMastersPBS American Masters – Edgar Allan Poe: Buried Alive Premieres nationwide Monday, October 30 at 9/8c on PBS (check local listings) for Halloween Edgar Allan Poe Bio & Timeline In biography the truth is everything. — Edgar Allan Poe Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston, January 19, 1809, the son of two actors. By the time he was three years old, his father had abandoned the family and his mother, praised for her beauty and talent, had succumbed to consumption. Her death was the first in a series of brutal losses that would resonate through Poe’s prose and poetry for the duration of his life. Poe was taken in by John Allan, a wealthy Richmond merchant and an austere Scotsman who believed in self-reliance and hard work. His wife, Francis, became a second mother to Poe – until, like Poe’s mother, she died. Allan, who had never formally adopted Poe, became increasingly harsh toward the young man and the two clashed frequently. Eventually, Poe left the Allan home, vowing to make his way in the world alone. By the time he was 20, Poe’s dreams of living as a southern gentleman were dashed. After abandoning a military career during which he published his first book of poetry, Poe landed in Baltimore and took refuge with an aunt, Maria Clemm, and her 13-year-old daughter, Virginia, whom he would later marry despite a significant age difference. -

THE HUMBUG Page 1 of 12 Ebscohost 8/12/2020

EBSCOhost Page 1 of 12 Record: 1 Title: THE HUMBUG. Authors: Lepore, Jill Source: New Yorker. 4/27/2009, Vol. 85 Issue 11, p65-71. 7p. 1 Color Photograph. Document Type: Article Subject Terms: *AMERICAN authors *AMERICAN horror tales *19TH century American literature *AMERICAN literature -- History & criticism *BIOGRAPHY (Literary form) 19TH century Geographic Terms: UNITED States People: POE, Edgar Allan, 1809-1849 Abstract: The article discusses the approach to writing of 19th-century American author Edgar Allan Poe. Poe's publishing career is discussed, as is the critical reception of his stories and poems of horror and mystery. The relation of his tales to the U.S. politics and economics of his time is also discussed, along with Poe's financial and mental instability. Full Text Word Count: 6040 ISSN: 0028-792X Accession Number: 37839147 Database: Academic Search Premier Section: A CRITIC AT LARGE THE HUMBUG Edgar Allan Poe and the economy of horror Edgar Allan Poe once wrote an essay called "The Philosophy of Composition," to explain why he wrote "The Raven" backward. The poem tells the story of a man who, "once upon a midnight dreary," while mourning his dead love, Lenore, answers a tapping at his chamber door, to find "darkness there and nothing more." He peers into the darkness, "dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before," and meets a silence broken only by his whispered word, "Lenore?" He closes the door. The tapping starts again. He flings open his shutter and, "with many a flirt and flutter," in flies a raven, "grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore." The bird speaks just one word: "Nevermore." That word is the poem's last, but it's where Poe began. -

Edgar Allan Poe and the Periodical Marketplace Spring 2009, VCU

Edgar Allan Poe and the Periodical Marketplace Spring 2009, VCU Instructor Course Dr. Les Harrison ENGL 611.902 324e Hibbs R, 7:00 – 9:40 [email protected] 3 credits 804-827-8334 (o) Office Hours 804-269-1023 (c) R, 12:00 – 2:00 This class will concentrate on Edgar Allan Poe as a periodical author in the context of the nineteenth-century literary marketplace. Readings will focus on those Poe tales and Poems which initially debuted in the periodical press. Student presentations will attempt to fully situate Poe within his nineteenth-century periodical context through analysis of the stories, advertisements, illustrations, and implied editorial and publication policies of the specific volumes in which his tales and poems first appeared. Throughout the course, special attention will be paid to the ways in which Poe and his nineteenth-century contemporaries wrote to the demands of a competitive, turbulent, and transforming market for periodical authors. Required Texts Cline, Patricia Cohen, Timothy J. Gilfoyle, Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, and the American Antiquarian Society. The Flash Press: Sporting Male Weeklies in 1840s New York. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2008. Lehuu. Isabelle. Carnival on the Page: Popular Print Media in AnteBellum America. Chapel Hill, N.C.: U of North Carolina P, 2000. Poe, Edgar Allan. Poe: Poetry, Tales, and Selected Essays. Library of America College Edition. New York: Library of America, 1996. Optional Texts Hawthorne, Nathaniel. Selected Tales and Sketches. Ed. Michael J. Colacurcio. New York: Penguin, 1987. McGill, Meredith L. American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting, 1834—1853. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2003. -

Illuminating Poe

Illuminating Poe The Reflection of Edgar Allan Poe’s Pictorialism in the Illustrations for the Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie beim Fachbereich Sprach-, Literatur- und Medienwissenschaft der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Christian Drost aus Brake Hamburg, 2006 Als Dissertation angenommen vom Fachbereich Sprach-, Literatur- und Medienwissenschaft der Universität Hamburg aufgrund der Gutachten von Prof. Dr. Hans Peter Rodenberg und Prof. Dr. Knut Hickethier Hamburg, den 15. Februar 2006 For my parents T a b l e O f C O n T e n T s 1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 2 Theoretical and methodical guidelines ................................................................ 5 2.1 Issues of the analysis of text-picture relations ................................................. 5 2.2 Texts and pictures discussed in this study ..................................................... 25 3 The pictorial Poe .......................................................................................... 43 3.1 Poe and the visual arts ............................................................................ 43 3.1.1 Poe’s artistic talent ......................................................................... 46 3.1.2 Poe’s comments on the fine arts ............................................................. 48 3.1.3 Poe’s comments on illustrations ........................................................... -

An Investigation of the Aesthetics of Edgar Allan Poe

Indefinite Pleasures and Parables of Art: An Investigation of the Aesthetics of Edgar Allan Poe The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37945134 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Indefinite Pleasures and Parables of Art: An Investigation of the Aesthetics of Edgar Allan Poe By Jennifer J. Thomson A Thesis in the Field of English for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2018 Copyright 2018 Jennifer J. Thomson Abstract This investigation examines the origins and development of Edgar Allan Poe’s aesthetic theory throughout his body of work. It employs a tripartite approach commencing with the consideration of relevant biographical context, then proceeds with a detailed analysis of a selection of Poe’s writing on composition and craft: “Letter to B—,” “Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales,” “The Philosophy of Composition,” “The Poetic Principle,” and “The Philosophy of Furniture.” Finally, it applies this information to the analysis of selected works of Poe’s short fiction: “The Assignation,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Oval Portrait,” “The Domain of Arnheim,” and “Landor’s Cottage.” The examination concludes that Poe’s philosophy of art and his metaphysics are linked; therefore, his aesthetic system bears more analytical weight in the study of his fiction than was previously allowed. -

THE HUMBUG Edgar Allan Poe and the Economy of Horror

A CRITIC AT LARGE THE HUMBUG Edgar Allan Poe and the economy of horror. by Jill Lepore The New Yorker Magazine APRIL 27, 2009 www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2009/04/27/090427crat_atlarge_lepore. Always in debt, Poe both sought and sneered at the popular audience of his day. Keywords Edgar Allan Poe; “On a Raven’s Wing: New Tales in Honor of Edgar Allan Poe” (Harper; $14.99); “In the Shadow of the Master: Classic Tales by Edgar Allan Poe” (William Morrow; $25.99); “Poe: A Life Cut Short” (Doubleday; $21.95); “The Raven”; “The Gold-Bug”; Writers Edgar Allan Poe once wrote an essay called “The Philosophy of Composition,” to explain why he wrote “The Raven” backward. The poem tells the story of a man who, “once upon a midnight dreary,” while mourning his dead love, Lenore, answers a tapping at his chamber door, to find “darkness there and nothing more.” He peers into the darkness, “dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before,” and meets a silence broken only by his whispered word, “Lenore?” He closes the door. The tapping starts again. He flings open his shutter and, “with many a flirt and flutter,” in flies a raven, “grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore.” The bird speaks just one word: “Nevermore.” That word is the poem’s last, but it’s where Poe began. He started, he said, “at the end, where all works of art should begin,” and he “first put pen to paper” at what became the third-to-last stanza: “Prophet,” said I, “thing of evil! prophet still if bird or devil! By that heaven that bends above us—by that God we both adore, Tell this soul with sorrow laden, if within the distant Aidenn, It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore— Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore.” Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.” 1 “The Philosophy of Composition” is a lovely little essay, but, as Poe himself admitted, it’s a bit of jiggery-pokery, too. -

The Faith, Innovation, & Mystery of Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849

The Faith, Innovation, & Mystery of Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849}--Revised Fall 2018 Reading Packet Session 2: Oct 22, 6:30-8 p.m. repeated Oct. 23, 9:30-11 a.m. “Even in the grave, all is not lost.’ --Poe, Pit & the Pendulum [Poe Portrait and Signature. The portrait is based on a daguerreotype taken just before Poe’s death (1849). The signature comes from am 1844 Poe letter now in the Huntington Library (California).] 2ND Session Readings 0. Overview 2nd Poe Session…………………………………………………………………1 1. Poe: England and Middle Years………………………………………………………1-2 2. Poe, first American Literary Critic………………………………………………….2-3 3. Rossetti, Blessed Damozel: Selections & Comment………………………….3-6 4. Poe, The Bells: the Poem, Definitions, Comment……………………………6-8 5. Rachmaninoff, The Bells (Op. 53)……………………………………………….....8-9 6. Readings & Selection on, Poe’s Poem Al Aaraaf …………………………..9-12 7. Poe Poem, Ianthe in Heaven………………………………………………………….12 8. Poe & his angry Biographer Rufus Griswold…………………………………12-13 Reading 0. Session 2 Overview. In this session, we continue our exploration of the “Poe we know” and the Poe we don’t know.” The readings begin with an account of Poe’s life from 1815 (his childhood in England) through 1836 (his departure from West Point). We then turn to Blessed Damozel, a sequel to The Raven written by English poet Daniel Gabriel Rossetti right after he read The Raven. The Rossetti poem focuses on the celestial Lenore’s lament for her grieving mortal lover. We will also explore 3 poems by Poe: The Bells and its impact on Russian composer Rachmaninoff; Al Aaraaf inspired by the Holy Quran and a Supernova; and the love poem To Ianthe in Heaven. -

The Works of Edgar Allan Poe – Volume 5

The Works of Edgar Allan Poe – Volume 5 By Edgar Allan Poe 1 CONTENTS: Philosophy of Furniture A Tale of Jerusalem The Sphinx Hop Frog The Man of the Crowd Never Bet the Devil Your Head Thou Art the Man Why the Little Frenchman Wears his Hand in a Sling Bon-Bon Some words with a Mummy The Poetic Principle Old English Poetry POEMS: Dedication Preface Poems of Later Life The Raven The Bells Ulalume 2 To Helen Annabel Lee A Valentine An Enigma To my Mother For Annie To F---- To Frances S. Osgood Eldorado Eulalie A Dream within a Dream To Marie Louise (Shew) To the Same The City in the Sea The Sleeper Bridal Ballad Notes Poems of Manhood Lenore To One in Paradise The Coliseum The Haunted Palace The Conqueror Worm Silence Dreamland 3 Hymn To Zante Scenes from "Politian" Note Poems of Youth Introduction (1831) Sonnet--To Science Al Aaraaf Tamerlane To Helen The Valley of Unrest Israfel To -- ("The Bowers Whereat, in Dreams I See") To -- ("I Heed not That my Earthly Lot") To the River -- Song A Dream Romance Fairyland The Lake To-- "The Happiest Day" Imitation Hymn. Translation from the Greek "In Youth I Have Known One" A Paean 4 Notes Doubtful Poems Alone To Isadore The Village Street The Forest Reverie Notes 5 PHILOSOPHY OF FURNITURE. In the internal decoration, if not in the external architecture of their residences, the English are supreme. The Italians have but little sentiment beyond marbles and colours. In France, meliora probant, deteriora sequuntur--the people are too much a race of gadabouts to maintain those household proprieties of which, indeed, they have a delicate appreciation, or at least the elements of a proper sense. -

Edgar Allan Poe - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Edgar Allan Poe - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Edgar Allan Poe(19 January 1809 - 7 October 1849) Edgar Allen Poe was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre. He is further credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction. He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career. <b>Early Life</b> He was born Edgar Poe in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 19, 1809, the second child of actress Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe and actor David Poe, Jr. He had an elder brother, William Henry Leonard Poe, and a younger sister, Rosalie Poe. Edgar may have been named after a character in William Shakespeare's King Lear, a play the couple was performing in 1809. His father abandoned their family in 1810, and his mother died a year later from consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis). Poe was then taken into the home of John Allan, a successful Scottish merchant in Richmond, Virginia, who dealt in a variety of goods including tobacco, cloth, wheat, tombstones, and slaves. The Allans served as a foster family and gave him the name "Edgar Allan Poe", though they never formally adopted him. The Allan family had Poe baptized in the Episcopal Church in 1812.