Some Thoughts on a Best Seller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions. In: Matthew S. Adams and Ruth Kinna, eds. Anarchism, 1914-1918: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 69-92. ISBN 9781784993412 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/20790/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] 85 3 Malatesta and the war interventionist debate 1914–17: from the ‘Red Week’ to the Russian revolutions Carl Levy This chapter will examine Errico Malatesta’s (1853–1932) position on intervention in the First World War. The background to the debate is the anti-militarist and anti-dynastic uprising which occurred in Italy in June 1914 (La Settimana Rossa) in which Malatesta was a key actor. But with the events of July and August 1914, the alliance of socialists, republicans, syndicalists and anarchists was rent asunder in Italy as elements of this coalition supported intervention on the side of the Entente and the disavowal of Italy’s treaty obligations under the Triple Alliance. Malatesta’s dispute with Kropotkin provides a focus for the anti-interventionist campaigns he fought internationally, in London and in Italy.1 This chapter will conclude by examining Malatesta’s discussions of the unintended outcomes of world war and the challenges and opportunities that the fracturing of the antebellum world posed for the international anarchist movement. -

Britskí Anarchisti V Medzivojnovom Období

Britskí anarchisti v medzivojnovom období Jakub DRÁBIK V poslednom období sa o „anarchizme“ začalo hovoriť vo všetkým možných súvislostiach. Tento termín sa začal používať čoraz viac a na čoraz väčšie množstvo udalostí, začína sa spájať s čoraz väčším počtom ľudí. Tým sa stáva neprehľadným a preto je v súvislosti s pojmom „anarchizmus“ nevyhnutné aspoň v stručnosti vysvetliť, čo vlastne tento pojem znamená. Pojem anarchizmus má často pejoratívny význam a je bežne považovaný za čosi negatívne, deštrukčné, je spájaný s násilím či terorizmom. Je to predovšetkým preto, že sa spája s konaním „samozvaných“ anarchistov, ktorí sa za anarchistov prehlasujú predovšetkým preto, aby mohli jednoducho ospravedlniť svoje kriminálne a neakceptovateľné správanie. Tým hnutie diskreditujú. Obsah pojmu „anarchizmus“ je chápaný predovšetkým v negatívnom zmysle ako ohrozenie všeobecného poriadku a existujúceho vládnuceho systému. Je pravdou, že anarchisti sa snažia zničiť akúkoľvek vládu, štát či cirkevnú hierarchiu. Túto svoju snahu vidia ale v pozitívnom zmysle, ako snahu o slobodu jednotlivca v slobodnom spoločenstve bez akejkoľvek nadvlády – či už ide o politickú, ekonomickú, náboženskú alebo nadvládu ktorá vychádza z rešpektovania istého hierarchického usporiadania spoločnosti. Anarchisti vidia príčinu všetkého zla a útlaku v moci jedného človeka nad druhým. Jedinec by podľa nich mal mať možnosť vždy sám rozhodovať o svojom živote a robiť si čo chce, aj keby proti tomu bola majoritná spoločnosť. Anarchisti uznávajú istú potrebu organizácie ľudí, no presadzujú ju na čo možno najnižšom stupni a čo je podstatné – na dobrovoľnej báze, teda bez štátu, cirkvi či nadriadeného alebo šéfa. Definovať pojem anarchizmus je ťažké, keďže nie je jednotným a súdržným súborom politických ideí (anarchisti vychádzajú z rôznych filozofických hľadísk a nezhodujú sa v tom, ako by mala vyzerať anarchistická spoločnosť, existuje viacero koncepcií a smerov anarchizmu ako anarchosyndikalizmus, anarchokomunizmus, mutualizmu, individualizmus a pod.). -

Sasha and Emma the ANARCHIST ODYSSEY OF

Sasha and Emma THE ANARCHIST ODYSSEY OF ALEXANDER BERKMAN AND EMMA GOLDMAN PAUL AVRICH KAREN AVRICH SASHA AND EMMA SASHA and EMMA The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich Th e Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts • London, En gland 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Karen Avrich. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Avrich, Paul. Sasha and Emma : the anarchist odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman / Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich. p . c m . Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 06598- 7 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Berkman, Alexander, 1870– 1936. 2. Goldman, Emma, 1869– 1940. 3. Anarchists— United States— Biography. 4 . A n a r c h i s m — U n i t e d S t a t e s — H i s t o r y . I . A v r i c h , K a r e n . II. Title. HX843.5.A97 2012 335'.83092273—dc23 [B] 2012008659 For those who told their stories to my father For Mark Halperin, who listened to mine Contents preface ix Prologue 1 i impelling forces 1 Mother Rus sia 7 2 Pioneers of Liberty 20 3 Th e Trio 30 4 Autonomists 43 5 Homestead 51 6 Attentat 61 7 Judgment 80 8 Buried Alive 98 9 Blackwell’s and Brady 111 10 Th e Tunnel 124 11 Red Emma 135 12 Th e Assassination of McKinley 152 13 E. G. Smith 167 ii palaces of the rich 14 Resurrection 181 15 Th e Wine of Sunshine and Liberty 195 16 Th e Inside Story of Some Explosions 214 17 Trouble in Paradise 237 18 Th e Blast 252 19 Th e Great War 267 20 Big Fish 275 iii -

Here Is Louise Michel This, People Could Say She Is a Pathological Case

Number 93-94 £1 or two dollars Mar. 2018 Here is Louise Michel this, people could say she is a pathological case. But there are thousands like her, millions, none of whom gives a damn about authority. They all repeat the battle cry of the Russian revolutionaries: land and freedom! Yes, there are millions of us who don’t give a damn for any authority because we have seen how little the many-edged tool of power accomplishes. We have watched throats cut to gain it. It is supposed to be as precious as the jade axe that travels from island to island in Oceania. No. Power monopolized is evil. Who would have thought that those men at the rue Hautefeuille who spoke so forcefully of liberty and who denounced the tyrant Napoleon so loudly would be among those in May 1871 who wanted to drown liberty in blood? [1] Power makes people dizzy and will always do so until power belongs to all mankind. Note 1, A swipe at moderate republicans who opposed the [Louise Michel (1830-1905) was back in prison Paris Commune: ‘Among the people associated with (again) in the 1880s when she wrote her memoirs the [education centre on] rue Hautefeuille was Jules (after the 1883 Paris bread riot). They were published Favre. At this time he was a true republican leader, but in February 1886. In this extract she looks back at her after the fall of Napoleon III he became one of those younger self, just before the Paris Commune of 1871.] who murdered Paris. -

12 Diciembre Mujer Y Memoria

1 MUJER Y MEMORIA DICIEMBRE 31 DE DICIEMBRE PAULETTE BRUPBACHER El 31 de diciembre de 1967 muere en Un- terendingen (Argovia, Suiza) la doctora y militante de los derechos de la mujer, compañera y colaboradora del libertario suizo Fritz Brupbacher, Pelta Rajgrodski (o Raygrodski), más conocida como Pau- lette ( Pauline o Paula ) Brupbacher . Ha- bía nacido el 16 de enero de 1880 a Pinsk (Polesia, Imperio Ruso; hoy Bielorrusia) en una familia acomodada judía. Sus pa- dres se llamaban Aron Hirsch Rajgrodski y Frieda Nimcowicz. En 1902 se casó en Berna (Berna, Suiza) con Abraham Goutzait, también ruso de origen judío, con quien tuvo una hija y un hilo - en estos años a ser conocida como Pelta Goutzait (o Paula Gutzeit).En 1902 comenzó a estudió Letras en la Universidad de Berna, donde las mujeres podían estudiar, y en 1907 se doctoró con una tesis sobre la reforma agraria del Imperio zarista ( Die Bodenreform ). En 1914 fue a Berlín a estudiar Medicina, pero con el estallido de la Gran Guerra retornó a Suiza. En estos años de estudio trabajó en una clínica para drogadictos. Finalmente se licenció en la Facultad de Medicina de Ginebra. En 1923 se divorció de Abraham Goutzait. Después se convertirá compañera de Fritz Brupbacher, con quien ejercerá desde 1924 la medicina en Zurich y compartirá su compromiso político, luchando espe- cialmente por la emancipación de la mujer y por los derechos a la contracepción, al divorcio, al aborto ya una libre sexualidad. La pareja se caracterizó por aceptar como pacientes a los sectores más desfavorecidos y perseguidos de la sociedad (trabajadores inmigrantes, refugiados políticos, disidentes, etc.) Y sus experiencias de estos años fueron explicadas en la obra Meine Patientinnen (1953) . -

The “ Rising” in Catalonia

I can really be free when those around me, both men and women, are also free. The li berty of others, far from limit ing or negating my own, is, on the contrary, its necessary con dition and guarantee. —B a k u n i n PRICE 2d— U.S.A. 5 CENTS. VOLUME 1, NUMBER 13. JUNE 4th, 1937. OPEN LETTER TO FEDERICA MONTSENY lAfclante, juventod; a luchar como titanes 1 By Camillo Berneri (This letter is taken from the Guerra di Classe of April 14th, 1937 (organ of the Italian Syndicalist Union, affiliated with the A IT ) published at Barcelona. It bears the signature of Camillo Bemert the well known militant anarchist, who, for several months, acted as the political delegate with the Errico Malatesta Battalion— and was addressed to Frederica Atont- seny, member of the Peninsular Committee of the F A I and Minister of Hygiene and Public Assistance in the Valencia Government. The text is reproduced almost in its entirety. The introduction only is missing—and that served solely to eliminate any personal animosity from the discussion by affirming the friendship and esteem of the signatory for his correspondent. — Eds.) REVOLUTIONARY SPAIN AND icith his practical realism, etc.” And I wholeheartedly approved of Voline’s THE POLICY OF reply in “Terre Libre” to your COLLABORATION thoroughly inexact statements on the Russian Anarchist Movement. H AVE not been able to accept But these are not the subjects I calmly the identity— which you I wish to take up with you now. On affirm— as between the Anarchism of these and other things, I hope, some Bakunin and the Federalist Republic day, to talk personally with you. -

Rudolf Rocker NELLA TORMENTA

Rudolf Rocker NELLA TORMENTA (Anni d’esilio) (1895 - 1918) Traduzione di Andrea Chersi LONDRA IL MOVIMENTO TEDESCO A LONDRA Era una mattina malinconica, grigia, quando di buonora arrivai a Londra, una di quelle mattine che si vedono solo nella gigantesca città sul Tamigi e che mi fece capire subito la differenza tra Parigi e Londra. In quei giorni, quando una nebbia umida e appiccicaticcia ottunde i sensi e gli occhi non ricevono altro che un’impressione cupa e torbida dell’ambiente intorno, ci si sente in un mondo spettrale. Perfino il frastuono del gigantesco traffico stradale arriva smorzato, come avvolto nell’ovatta. Gli esseri umani passano come ombre al crepuscolo. Tutto affonda in un grigiore triste e giallognolo che contagia tutti i sensi e ricade oppressivamente sull’animo. Chi giunge a Londra in una di queste giornate, quando King Fog avvolge la città nel suo manto, non lo dimentica più. Non avevo comunicato agli amici quando sarei arrivato, sicché nessuno mi attendeva alla stazione. Avendo parecchi bagagli, presi un hansom, una di quelle carrozze a due ruote che allora si vedevano solo in Inghilterra e che in una mezz’ora mi condusse a Wardour Street, dove abitava il mio amico Gundersen. Questi mi salutò con allegra sorpresa e dopo avere chiacchierato un po’ c’incamminammo verso l’alloggio di Wilhelm Werner, che a quel tempo non era distante, in Cleveland Street. Trovammo a casa tutta la famiglia e siccome nessuno mi aspettava, la gioia dell’incontro fu tanto maggiore. Avevamo molto da raccontarci, da quando ci eravamo visti per l’ultima volta a Berlino. -

Pierre Ramus Papers (1826, 1872-) 1882-1936 (-1991)1882-1936

Pierre Ramus Papers (1826, 1872-) 1882-1936 (-1991)1882-1936 International Institute of Social History Cruquiusweg 31 1019 AT Amsterdam The Netherlands hdl:10622/ARCH01162 © IISH Amsterdam 2020 Pierre Ramus Papers (1826, 1872-) 1882-1936 (-1991)1882-1936 Table of contents Pierre Ramus Papers....................................................................................................................... 5 Context............................................................................................................................................... 5 Content and Structure........................................................................................................................5 Access and Use.................................................................................................................................6 Allied Material.....................................................................................................................................7 Appendices.........................................................................................................................................7 I N V E N T A R............................................................................................................................ 43 ALLGEMEIN.............................................................................................................................. 43 Korrespondenz..................................................................................................................43 -

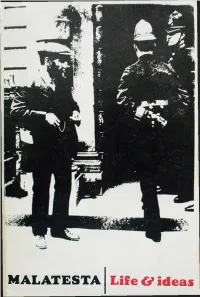

MALATESTA His Life Ideas

M ALATESTA Life & id eas ERRICO MALATESTA His Life Ideas Compiled and Edited by VERNON RICHARDS m m i i ® 2 9 3 4 Ri/E ST-URSAiH, MONTREAL 131 T*L 15145 844-4076 LONDON FREEDOM PRESS 1965 First Published 1965 by FREEDOM PRESS 17a Maxwell Road, London, S.W.6 Printed by Express Printers London, E.l Printed in Gi. Britain To the memory of Camillo and Giovanna Berneri and their daughter Marie-Louise Berneri CONTENTS Editor’s Foreword PaSe 9 P a r t O n e Introduction: Anarchism and Anarchy 19 I 1 Anarchist Schools of Thought 29 2 Anarchist-Communism 34 3 Anarchism and Science 38 4 Anarchism and Freedom 47 5 Anarchism and Violence 53 6 Attentats 61 it 7 Ends and Means 68 8 Majorities and Minorities 72 9 Mutual Aid 93 10 Reformism 98 11 Organisation 83 in 12 Production and Distribution 91 13 The Land 97 14 Money and Banks 100 15 Property 102 16 Crime and Punishment 105 IV 17 Anarchists and the Working Class Movements 113 18 The Occupation of the Factories 134 19 Workers and Intellectuals 137 20 Anarchism, Socialism and Communism 141 21 Anarchists and the Limits of Political Co-Existence 148 v 22 The Anarchist Revolution 153 23 The Insurrection 163 24 Expropriation 167 25 Defence of the Revolution 170 VI 26 Anarchist Propaganda 177 27 An Anarchist Programme 182 P a r t Two Notes for a Biography (V.R.) 201 Source Notes 241 A PPEN D IC ES I Anarchists have forgotten their Principles (E.M. -

Italian Anarchists in London (1870-1914)

1 ITALIAN ANARCHISTS IN LONDON (1870-1914) Submitted for the Degree of PhD Pietro Dipaola Department of Politics Goldsmiths College University of London April 2004 2 Abstract This thesis is a study of the colony of Italian anarchists who found refuge in London in the years between the Paris Commune and the outbreak of the First World War. The first chapter is an introduction to the sources and to the main problems analysed. The second chapter reconstructs the settlement of the Italian anarchists in London and their relationship with the colony of Italian emigrants. Chapter three deals with the activities that the Italian anarchists organised in London, such as demonstrations, conferences, and meetings. It likewise examines the ideological differences that characterised the two main groups in which the anarchists were divided: organisationalists and anti-organisationalists. Italian authorities were extremely concerned about the danger represented by the anarchists. The fourth chapter of the thesis provides a detailed investigation of the surveillance of the anarchists that the Italian embassy and the Italian Minster of Interior organised in London by using spies and informers. At the same time, it describes the contradictory attitude held by British police forces toward political refugees. The following two chapters are dedicated to the analysis of the main instruments of propaganda used by the Italian anarchists: chapter five reviews the newspapers they published in those years, and chapter six reconstructs social and political activities that were organised in their clubs. Chapter seven examines the impact that the outbreak of First World Word had on the anarchist movement, particularly in dividing it between interventionists and anti- interventionists; a split that destroyed the network of international solidarity that had been hitherto the core of the experience of political exile. -

04 Abril Mujeres Y Memoria

1 MUJER Y MEMORIA ------------------------------------- ABRIL SIMONE LARCHER El 30 de abril de 1903 nace en Montataire la co- rrectora de imprenta, antimilitarista y militante anarquista Rachel Willissek, más conocida como Simone Larcher. Con 22 años fue detenida y con- denada el 19 de agosto a seis meses de prisión por haber distribuido un folleto antimilitarista. Al- gunos meses después de su liberación, en 1926 pone en marcha con su compañero Louis Louvet, como miembros de la Juventud Anarquista Autó- noma, la publicación del periódico “L’Anarchie”. Simone se convirtió en correctora de imprenta, desde 1928, y será la primera mujer a formar parte del Comité Sindical de los Correctores en 1941. Después de la guerra, de diciembre 1944 a noviembre 1948, Louvet y Lar- cher editaron una nueva edición del periódico de Sébastien Faure “Ce Qu’il Faut Dire” del cual salieron 60 números, y colabora también en “Le Libertaire”, “La Eveil des Jeunes Libertaires” (1925-1926) y en la revista francoespañola publicada por el MLE “Universo” (1946-1948) CLARA CAMPOAMOR El 30 de abril de 1972 muere en Suiza Clara Cam- poamor, exiliada, enferma de melancolía, casi ciega y olvidada de todos y por todos. Fue la diputada de izquierdas que luchó y por fin logró el voto femenino en España en 1931. Por ello, primero fue humillada por la izquierda republicana y después el régimen franquista que le prohibió su vuelta del exilio y la re- legó al silencio por roja y masona. 2 MADRES DE LA PLAZA DE MAYO El 30 de abril de 1977 se reúnen frente a la Casa Rosada de la plaza de Mayo de Buenos Aires 14 mujeres, madres de desaparecidos, torturados y asesinados por la dictadura militar. -

Black Flag Supplement

-I U The oodcock - Sansom School of Fals|f|cat|o (Under review: the new revised edition of Geo. Woodcock’s no mnnection with this George Spanish). The book wrote the Anarchists off ‘Anarchism’, published by Penguin books; the Centenary Edition Woodcock! Wrote all essay 111 3 trade altogether. The movement was dead. of ‘Freedom’, published by Freedom Press.) ‘figiggmfii“,:§°:i;mfit‘3’§ar’§‘,ia’m,‘§f“;L3;S, He was its ‘obituarist’. Now he has fulsome praise of his ‘customary issued a revised version of the book brilliance (he had only written one brought up ‘to date’. He wasn’t HEALTH WARNING; Responses to preparing for a three volume history °i3iiei' Pieee) and ’iiiei5iVe insight’ " it wrong, he says, it did die — but his (‘I find the influence of Stirner on was a Pavlovian response from his book brought it back to life again! Freedom Press clique have been namesake’s coterie. It explains what It adds a history’ of the British described by our friends as ‘terminally British anarchism very interesting. .’) The Amsterdam Institute for Social this George Woodcock set out movement for his self-glorification, boring’ but can we let everything History, funded by the Dutch govem- steadily to build up. actually referring to the British pass? We suggest using this as a ment, now utilises the CNT archives He came on the anarchist scene delegate to the Carrara conference supplement to either ‘Anarchism’ or to establish itself (to quote Rudolf de during the war, profiteering on the denouncing those who pretended to ‘Freedom Centennial’, especially when Jong) as ‘paterfamilias’ between the boom in anarchism to get into the be anarchists but were so in name you feel tired of living.