Adolescent Girls in Mumbai's Bastis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syndicate Bank Exam 2018 Current Affairs

A2Z Current Affairs PDF for Syndicate Exam 2018 www.aspirantszone.com A2Z Current Affairs PDF for upcoming exams www.aspirantszone.com υ www.aspirantszone.com|Doload AspiatsZoes Mobile App | Like us on Facebook A2Z Current Affairs PDF for Syndicate Exam 2018 www.aspirantszone.com Contents Topic Page Number MOU/Agreement Countries 3 MOU Industry/States/Others 3-5 Appointments and Resignations 5-8 Awards and Recognitions 8-12 Conference and Summits 13-16 International News 17-20 National News 20-29 State News 30-37 Finance and Banking News 37-42 Business News 42-43 Economy News 43-47 Science & Technology 47 Defence News 47-49 Sports News 49-50 Committees 50-56 Rankings of Countries 57-58 Rankings (Persons and Organisations) 58 Loans from Banks 58-59 Deadlines 59-60 Books and Authors 60 Obituaries 61-63 Nobel Prize Winners 63 Important Days(Jan-March) 63-65 φ www.aspirantszone.com|Doload AspiatsZoes Mobile App | Like us on Facebook A2Z Current Affairs PDF for Syndicate Exam 2018 www.aspirantszone.com MOU/Agreement Countries India Myanmar Agreement on restoration of normalcy and development of the Rakhine State, from where thousands of Rohingya Muslims recently fled following incidents of violence against the community. India Russia Russia will assist India to set up a national crisis management centre in the country to handle disaster and other emergency situations. India Mauritius India will offer technical support and advisory services in implementing DigiLocker service in Mauritius. Myanmar Bangladesh For the return of over six lakh Rohingya Muslims who had fled to Bangladesh to escape a violent crackdown by the Myanmar military. -

![Jinal Mukesh Sangoi Jinalmsangoi[At]Gmail[Dot]Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6170/jinal-mukesh-sangoi-jinalmsangoi-at-gmail-dot-com-1326170.webp)

Jinal Mukesh Sangoi Jinalmsangoi[At]Gmail[Dot]Com

Jinal Mukesh Sangoi jinalmsangoi[at]gmail[dot]com Education: 2018 Master of Fine Arts, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, California, USA Mentors: Michael Ned Holte, Karen Atkinson, Clara López Menéndez, Robert Dansby 2015 Bachelor of Fine Arts, Rachana Sansad Academy of Fine Arts and Craft, Mumbai, India Mentors: Amrita Gupta Singh, Sudhir Pandey 2011 Master of Commerce, University of Mumbai, India 2010 Certificate of Teachers in Hand Craft and Work Experience, Maharashtra State Board of Vocational Examinations, Mumbai, India 2009 Bachelor of Commerce, R. A. Podar College of Commerce and Economics, Mumbai, India Residencies: 2020 Yaddo, New York, USA (Upcoming - postponed to 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic) 2019 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine, USA 2018-19 The REEF Residency, Los Angeles, USA 2014 CRACK International Art Camp, Kushtia, Bangladesh Awards/Scholarships/Grants: 2020 Best Art Installation Award (first prize), Kala Ghoda Arts Festival, for Agastya International Foundation, Mumbai, India 2019 Full Scholarship, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine, USA 2018 Gender Bender Grant, Goethe-Institut Max Mueller Bhavan, Bangalore, India 2017 Tim Disney Prize for Excellence in Storytelling Arts, CalArts, USA Provost Merit Scholarship, California Institute of the Arts, USA Chiquita Landfill Found Art Scholarship, California Institute of the Arts, USA 2016 Provost Merit Scholarship, California Institute of the Arts, USA 2015 Certificate of Excellence, Rachana Sansad Academy of Fine Arts and Crafts, Mumbai, India 2013 Best Poem on Post Card, India Post and Katha Kosa, Mumbai, India Best Student Award, Rachana Sansad Academy of Fine Arts and Crafts, Mumbai 2010 Best Student Award, Dr. -

Goa & Mumbai 8

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Goa & Mumbai North Goa p121 Panaji & Central Goa p82 Mumbai South Goa (Bombay) p162 p44 Goa Paul Harding, Kevin Raub, Iain Stewart PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to MUMBAI PANAJI & Goa & Mumbai . 4 (BOMBAY) . 44 CENTRAL GOA . 82 Goa & Mumbai Map . 6 Sights . 47 Panaji . 84 Goa & Mumbai’s Top 14 . .. 8 Activities . 55 Around Panaji . 96 Need to Know . 16 Courses . 55 Dona Paula . 96 First Time Goa . 18 Tours . 55 Chorao Island . 98 What’s New . 20 Sleeping . 56 Divar Island . 98 If You Like . 21 Eating . 62 Old Goa . 99 Month by Month . 23 Drinking & Nightlife . 69 Goa Velha . 106 Itineraries . 27 Entertainment . 72 Ponda Region . 107 Beach Planner . 31 Shopping . 73 Molem Region . .. 111 Activities . 34 Information . 76 Beyond Goa . 114 Travel with Children . 39 Getting There & Away . 78 Hampi . 114 Getting Around . 80 Anegundi . 120 Regions at a Glance . .. 41 TUKARAM.KARVE/SHUTTERSTOCK © TUKARAM.KARVE/SHUTTERSTOCK © GOALS/SHUTTERSTOCK TOWERING ATTENDING THE KALA GHODA ARTS FESTIVAL P47, MUMBAI PIKOSO.KZ/SHUTTERSTOCK © PIKOSO.KZ/SHUTTERSTOCK STALL, ANJUNA FLEA MARKET P140 Contents UNDERSTAND NORTH GOA . 121 Mandrem . 155 Goa Today . 198 Along the Mandovi . 123 Arambol (Harmal) . 157 History . 200 Reis Magos & Inland Bardez & The Goan Way of Life . 206 Nerul Beach . 123 Bicholim . .. 160 Delicious India . 210 Candolim & Markets & Shopping . 213 Fort Aguada . 123 SOUTH GOA . 162 Arts & Architecture . 215 Calangute & Baga . 129 Margao . 163 Anjuna . 136 Around Margao . 168 Wildlife & the Environment . .. 218 Assagao . 142 Chandor . 170 Mapusa . 144 Loutolim . 170 Vagator & Chapora . 145 Colva . .. 171 Siolim . 151 North of Colva . -

Annual Report 2016-17

Annual Report 2016-17 i Annual Report 2016 -17 ii Contents • Executive Summary 3 • About MMC 5 Vision 5 Mission 5 History 5 Our Approach 5 • Our Children 8 Children Reached 8 Migration 9 Length of Stay 9 Linguistic Diversity 9 • Education 10 Enrolment of Children in Schools 10 Strengthening and Enhancing Our Education Programme 13 • Health & Nutrition 18 Health 18 Nutrition 22 • Community Outreach 27 Interactions with the Community 27 Facilitation of the Resources for the Community 29 Interactions with Youth 30 • Training 31 Bal Palika Training 31 Bal Vikas Sahyog Training 33 Puppet Workshops 33 • Our Partners 34 Government 34 Non-profit Organisations 34 Hospitals 35 Builders & Contractors 35 1 • Organisational Development 36 Institutional Strengthening Initiatives 36 Building Capacities of Staff 37 • Travel 38 National 38 International 39 • Governance 40 Our Board 40 Details of Board Meetings 40 • Financials 41 Income & Expenditure Account 41 Abridged Balance Sheet 42 Receipts & Payments 43 Auditors, Legal Advisor & Bankers 44 Registrations 44 Salaries & Benefits 45 • Volunteers 46 Friends of MMC 46 Social Media 46 • Supporters 47 Donations: Individuals 49 Donations & Earmarked Grants: Organisations, Trusts & Foundations 49 Donations & Earmarked Grants: Corporates 50 Donations in Kind 50 • Centres Operated 51 Photographs: Front Cover - Mumbai Mobile Creches & Back Cover - Ms. Shweta Agarwal, Mr. Navin Umaid Chaudhary and Ms. Cornelia Rummel 2 Executive Summary Dear Friends, to parents and the community, benefitting over 9000 people on a wide range of socio- With the close of the financial year 2016-17, economic issues. We further strengthened Mumbai Mobile Creches has completed 44 the quality of our Bal Palika Training years of successfully providing comprehensive programme by creating visual media for care for the children of migrant workers instruction. -

General-STATIC-BOLT.Pdf

oliveboard Static General Static Facts CLICK HERE TO PREPARE FOR IBPS, SSC, SBI, RAILWAYS & RBI EXAMS IN ONE PLACE Bolt is a series of GK Summary ebooks by Oliveboard for quick revision oliveboard.in www.oliveboard.in Table of Contents International Organizations and their Headquarters ................................................................................................. 3 Organizations and Reports .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Heritage Sites in India .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Important Dams in India ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Rivers and Cities On their Banks In India .................................................................................................................. 10 Important Awards and their Fields ............................................................................................................................ 12 List of Important Ports in India .................................................................................................................................. 12 List of Important Airports in India ............................................................................................................................. 13 List of Important -

CHILDREN Saturday

Saturday - 4th Feb: Kala Ghoda Schedule CHILDREN Title Location Time Description Methodical Max Mueller 11.00 am - Workshop in Origami with CSA By Bhavan Gate 01.00 pm Nilesh Shaharkar Special Workshop For Special Max Mueller 11.00 am - Ami Kothari in a creative session with Children Bhavan Gate 12.00 pm Little Angel Foundation. (children with mental disabilities) Post Office Adventures Entrance Gate 2.30 pm - Mumbai GPO is the biggest Post of GPO, Fort 3.30 pm Office in the country and one of the biggest in the world! Join Kruti as she takes you on a tour through this magnicificent structure. (ages 8 - 13) Speak with Paper Max Mueller 3.30 pm - Paper bag decoration with recycled Bhavan Gate 5.30 pm paper by Amruta Pathre (ages 9 - 15) Wonderful Wire Craft Max Mueller 4.00 pm - Watch and learn with Colaba's street Bhavan Gate 5.00 pm artist Harish. (9 yrs & above) Hanging Gardens Max Mueller 5.30 pm - Creating fresh flower hanging Bhavan Gate 7.00 pm arrangements with roots ribbons and crystals with Vibha Gupta (ages 10 - 15) [NOTE: Kids section can get crowded on the Weekends] www.wonderfulmumbai.com FOOD Title Location Time Description Asian Chef of the year 5 All Day, Hotel 4.00 pm - Embark on a 'food-art' journey with Milind Milind Sovani and Apollo, Colaba 6.00 pm and Asha as they give you priceless tips on Asha Khatau Causeway eyecatching presentations of Indian cuisine. www.wonderfulmumbai.com FILM Title Location Time Description REGIONAL GEMS Adaminte Makan Abu Max Mueller 2.30 pm - India’s Entry for the Oscars is about an Malayalam (101 min) Bhavan 4.30 pm elderly couple yearning to go on Haj. -

Mumbai-Shanghai Sister Cities Agreement: Challenges

Published by Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations 3rd floor, Cecil Court, M.K.Bhushan Marg, Next to Regal Cinema, Colaba, Mumbai 400 005 T: +91 22 22023371 E: [email protected] W: www.gatewayhouse.in Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations is a foreign policy think tank in Mumbai, India, established to engage India’s leading corporations and individuals in debate and scholarship on India’s foreign policy and the nation’s role in global affairs. Gateway House is independent, non-partisan and membership-based. Editor: Nandini Bhaskaran Cover design: Debarpan Das Layout: Virpratap Vikram Singh All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the written permission of the publisher. © Copyright 2017, Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 MUMBAI-SHANGHAI SISTER CITIES AGREEMENT: 5 CHALLENGES & OPPORTUNITIES 2.1. Introduction 5 2.2. Objectives of report 5 2.3. Meaning of Sister Cities 5 2.4. Shared history: Mumbai and the making of Shanghai 5 2.5. Challenges in furthering the Sister Cities relationship 6 2.6. Successful templates followed by other countries in Mumbai and Shanghai 8 GATEWAY HOUSE RECOMMENDS 9 3.1. Launch a Mumbai-Shanghai Forum 9 3.2. Collaboration between the two city governments through JWGs 10 3.3. Bring ongoing projects under the Agreement 10 3.4. Initiate cultural exchanges 10 3.5. Think tank to think tank (T2T) 11 3.6. -

Concept Note: Salaam Bombay Foundation Proudly Presents the First Edition of Our Initiative Voices. Voices Is an Inter- Scho

Concept Note: Salaam Bombay Foundation proudly presents the first edition of our initiative Voices. Voices is an inter- school peer learning platform via the performing and visual arts. For the children, by the children, to the children, it provides them with an opportunity for creative self-expression through original performances in the form of one act plays, songs and posters. Voices also seek to engage tomorrow’s generation in discussions through the arts on socially relevant issues and to sow the seeds of social responsibility early on in life. Topics are relevant to their lives today: the challenges they face, the stress or joy of being a child in the present times, amongst others. In creative expression, through the mediums of theatre, music and art, Voices will attempt to explore the following subjects 1. Life in a Metro - What is life for an average child in a city like Mumbai? Working parents, pollution, disappearing play areas, potential career opportunities, study pressure, infrastructure, sanitation. For better or for worse, it’s Aamchi Mumbai. The children will tell us how we can make our city better 2. Mujhse Dosti Karoge - Friends are made early. Friends are made easily. Friends influence us - good and bad. Where do we draw the line? What is peer pressure? Is it all bad? 3. No cigarette, no gutkha - Life Se Panga Mat Le Yaar - Substance abuse plagues our youth. India has the largest amount of tobacco users in the world and 70% start before their teens. Every 3 seconds, an Indian child tries tobacco for the first time. -

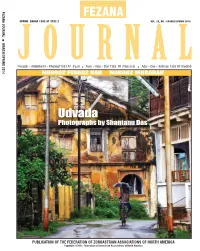

Spring 2014-Ver04.Indd

ZOROASTRIAN SPORTS COMMITTEE With Best Compliments is pleased to announce from ththth The Incorporated Trustees The 14 Z Games of the July 2-6, 2014 Zoroastrian Charity Funds of Cal State Dominguez Hills Los Angeles, CA, USA Hongkong, Canton & Macao ONLINE REGISTRATION NOW OPEN! www.ZATHLETICS.com www.zathletics.com | [email protected] FOR UP TO THE MINUTE DETAILS, FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA @ZSports @ZSports ZSC FEZANA JOURNAL PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 1 March / Spring 2014, Bahar 1383 AY 3752 Z 2224 36 60 02 Editorials 83 Behind the Scenes 122 Matrimonials 07 FEZANA Updates Firoza Punthakey-Mistree and 123 Obituary Pheroza Godrej 13 FEZANA Scholarships 126 Between the Covers Maneck Davar 41 Congress Follow UP FEZANA JOURNAL Ashishwang Irani Darius J Khambata welcomes related stories 95 In the News from all over the world. Be Khojeste Mistree a volunteer correspondent 105 Culture and History Dastur Peshotan Mirza or reporter 114 Interfaith & Interalia Dastur Khurshed Dastoor CONTACT 118 Personal Profile Issues of Fertility editor(@)fezana.org 119 Milestones Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, lmalphonse(@)gmail.com Language Editor: Douglas Lange Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, ffitch(@)lexicongraphics.com Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia bpastakia(@)aol.com Cover design Columnists: Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi: rabadis(@)gmail.com; Feroza Fitch -

Kala Ghoda Arts Festival 2019 to Mark 20 Years of Art and Culture ! by : INVC Team Published on : 31 Jan, 2019 12:02 AM IST

Kala Ghoda Arts Festival 2019 to mark 20 years of art and culture ! By : INVC Team Published On : 31 Jan, 2019 12:02 AM IST INVC NEWS New Delhi , Kala Ghoda Arts Festival (KGAF), India’s biggest cultural street festival, is all set to deliver this year an enthralling commemoration of 20 years since its inception. KGAF 2019 will celebrate 2 glorious decades of art and culture, across various forms and communities including design, cinema, theatre, dance, literature and much more, from 2nd to 10th February 2019 at the iconic art district of Kala Ghoda. This year also marks 150 years of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth, and the festival will pay its respects to his philosophy and contribution to the nation as well. Speaking on the 20 years of the iconic festival’s achievements, Maneck Davar, Hon Chairman of Kala Ghoda Association said, “It is a milestone year for us and everybody who has been involved with the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival, right since its inception. Come February 2nd, all art and creative enthusiasts the world over, will come and showcase their talent in the finest way possible. The festival has always been inclusive, providing information and entertainment to all demographics and social and economic strata, without any charge. It is a wondrous, cumulative effort of artists and artisans, curators and volunteers who make the festival a true celebration of culture. This year we also pay homage to the Father of the Nation on his 150th birth anniversary by a special exhibition at the Jehangir Art Gallery and through programs in music, dance, literature, theatre and more.” Talking about what the festival has in store as it turns 20, Nicole Mody, Festival Coordinator of KGAF, said, “The creative hub of Kala Ghoda, over the course of 20 years, has always acknowledged the various communities that are involved in the visual and performing arts industry. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1849 , 14/05/2018 Class 7 1721888 14/08

Trade Marks Journal No: 1849 , 14/05/2018 Class 7 Priority claimed from 30/04/2008; Application No. : 77462153 ;United States of America 1721888 14/08/2008 EATON CORPORATION 1000 EATON BOULEVARD CLEVELAND OHIO 44122 USA . AN COMPANY INCORPORATED UNDER THE LAWS OF UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Address for service in India/Attorney address: DUBEY & PARTNERS 601 DLF TOWER, TOWER-A, PLOT NO. 10-11 DDA DISTT. CENTRE JASOLA NEW DELHI-110044 Proposed to be Used DELHI HYDRAULIC PUMPS, HYDRAULIC MOTORS, VALVES, HYDRAULIC CYLINDERS, ELECTROHYDRAULIC VALVES, ACTUATORS, ACCUMULATORS, AND CONNECTORS. 1052 Trade Marks Journal No: 1849 , 14/05/2018 Class 7 4DX 2149826 25/05/2011 CJ 4DPLEX CO., LTD 164-1 JEUNGSAN-DONG, EUNPYEONG-GU, SEOUL, REPUBLIC OF KOREA MANUFACTURER AND MERCHANT A KOREAN CORPORATION Address for service in India/Attorney address: SHARDUL AMARCHAND MANGALDAS & CO. AMARCHAND TOWERS, 216, OKHLA INDUSTRIAL ESTATE-PHASE III, NEW DELHI 110020 Proposed to be Used To be associated with: 2022627 DELHI MACHINES FOR USE IN CREATING MOVIES AUDIENCE EFFECTS; AIR BLOWERS; BLOWING MACHINES FOR THE COMPRESSION, EXHAUSTION AND TRANSPORT OF GASES; ELECTRIC MOTORS FOR MACHINES, OTHER THAN FOR VEHICLES; AUTOMATIC HANDLING MACHINES; ROBOTS 1053 Trade Marks Journal No: 1849 , 14/05/2018 Class 7 Priority claimed from 11/07/2011; Application No. : 010113124 ;Germany 2254102 21/12/2011 SM MOTORENTEILE GMBH ALLEENSTR. 70, 71679 ASPERG, GERMANY MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS/TRADERS A COMPANY INCORPORATED UNDER THE LAWS OF GERMANY Address for service in India/Agents -

Pearl Academy Offers UG & PG Courses in Design, Fashion

PearlPearl Academy Academy offers offers UG & UG PG &courses PG courses in Design, in Design, Fashion, Fashion, Business, Business, Journalism Journalism and Media.and Media. To knowTo know more, more, visit www.pearlacademy.comvisit www.pearlacademy.com or call or 1800 call 1800 103 3005103 3005 (Toll Free).(Toll Free). DELHIDELHI • NOIDA • NOIDA • MUMBAI • MUMBAI • JAIPUR • JAIPUR COVER - 22-12-17 __AA.indd 1 22/12/17 8:13 pm The world looks forward to that answer just as much as you. Because you are made to change the world. You’ve chosen, the bold, and often intimidating path to create. You’re much like the man who invented the wheel, or he who declared that the world is not flat. You’re here, as much to learn the principles of design and communication, as to redefine the conventions of the past. There will be lots of learning, and even more eye-opening. It’s bound to be hard, it promises to be fun. It’ll be as much as about true grit, as it’ll be about real genius. he world looks forward to this impending discovery of yourself as much as you do. Because, while today is the first day of the rest of your life; in a sense, it’s also the first day of the rest of the world. Isn’t that amazing? Whether you are studying Product Design or Communication Design or Interiors or Fashion or Journalism – You are all creators. And being a creative person comes with an unyielding desire to raise the bar in every respect.