Impact Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is a Materials Recovery Facility? a Materials Recovery Facility (MRF

What is a Materials Recovery Facility? A materials recovery facility (MRF) is a specialized plant that receives, separates and prepares recyclable materials for sale to end-user manufacturers. It is important that the materials which come out of the MRF are clean, properly sorted and relatively free of impurities. How It Works Step 1: It All Starts with YOU! You begin by preparing your recyclables (e.g., you rinse bottles and cans, flatten cardboard) and place them in the residential recycling bin at the curb. Step 2: Materials are Collected and Delivered to a MRF Recycling crews drive through your neighborhood and collect the materials. They transport the materials to a MRF where they are weighed and offloaded onto the floor. Step 3: Recyclables are Put on Conveyor Belts Commingled materials (i.e., steel cans, aluminum cans, plastic bottles, cardboard and mixed paper) are put onto conveyors that are used to transport the material streams inside the MRF. Step 4: Materials are Sorted The conveyors go past semi-automated sorting lines. In this process, workers remove debris and sort the materials by type. In addition to hand sorting, materials undergo both simple and complex automated processes. For example, disc screens separate fiber from containers and 2-D from 3-D materials. While an overhead magnet is used to remove steel cans from other recyclables. Step 5: Recyclables are Prepared for Transport Once recyclables have gone through all the necessary sorting processes, they are prepared for transport. Some materials (i.e., plastics, metal cans, paper, cardboard) are compressed into large dense cubes or bales. -

5.0 Kerbside Contents

WEEE Collection Good Practice Guidance 1 5.0 Kerbside Contents 5.1 Bulky waste 01 5.1.1 Interacting with local reuse schemes 01 5.1.2 Identifying reusable items 02 5.1.3 Collection arrangements 02 5.2 Staff training 04 5.3 Handling and storage 05 5.4 Contractual arrangements 06 5.5 Small Mixed WEEE collections 07 WEEE Collection Good Practice Guidance 1 Audience: The primary audience for this section of the guidance is waste collection authorities (and their contractors). However, third sector organisations and producer compliance schemes will also be interested in this guidance. Benefits: The benefit to the collection authorities of implementing this good practice is to maximise the WEEE that is segregated for reuse and recycling through their kerbside/bulky waste collections. Producer compliance schemes will find this section of interest as they can benefit from innovative collection methods and may wish to discuss appropriate approved recycling and reuse routes with the local authorities. Third sector organisations will find the guidance of value by understanding how they can support waste collection authorities to maximise diversion of WEEE for reuse. Summary: This chapter considers the options available to waste collection authorities for maximising reuse and recycling of WEEE, through kerbside/ bulky waste collections, bring banks and ad hoc collections such as WEEE amnesties. Advice is therefore provided on how to identify reusable items, how to raise awareness of reuse avenues with householders and how to interact with local reuse schemes so they provide the level of service required. Useful sources of information of relevance to this section of the guidance are available from the Furniture Reuse Network. -

Standardising Kerbside Collections in Aotearoa

Recommendations for standardisation of kerbside collections in Aotearoa Prepared for Ministry for the Environment May 2020 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STANDARDISATION OF KERBSIDE COLLECTIONS IN AOTEAROA DOCUMENT QUALITY CONTROL Version Date Written by Distributed to Sarah Pritchett (WasteMINZ) and Draft 0.1 29 May 2020 Sunshine Yates (Sunshine Stephen Goodman Yates Consulting) on behalf of WasteMINZ Sarah Pritchett and Draft 0.2 10 June 2020 Stephen Goodman Sunshine Yates Sarah Pritchett and Final 1.0 26 June 2020 Stephen Goodman Sunshine Yates CONTACT DETAILS Ministry for the Environment WasteMINZ Stephen Goodman Sarah Pritchett Policy Manager Sustainability Advisor 23 Kate Sheppard Place PO Box 305426 Thorndon Triton Plaza Wellington 6143 Auckland 0757 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Project Managers acknowledges the time, expertise and guidance provided by the members of the Steering Group and Oversight Group in preparing this report. Steering Group Oversight Group Duncan Wilson (Chair) - Eunomia Research and Consulting Stephen Goodman (Chair) - MfE Mike Jones - Earthcare Environmental Shaun Lewis - MfE Rick Thorpe - Xtreme Zero Waste/Zero Waste Network Parul Sood - Auckland Council Rob Wilson - Eco Central Jason Krupp - Local Government New Zealand Angela Atkins - Hastings District Council Pamela Ritchie - MfE Janine Brinsdon - WasteMINZ Rodrick Boys - MfE Stephen Goodman - MfE The Project Managers also thank each and every local authority representative and waste and resource recovery industry representative that generously gave of their time and expertise -

Waste Management Guidance for Residents

Kent County Council Waste Management Guide to household waste disposal Guidance document for residents September 2019 4 kent.gov.uk This document can be made available in other formats or languages. To request this, please email [email protected] or telephone 03000 421553 (text relay service 18001 03000 421553). This number goes to an answer machine, which is monitored during office hours. Or write to: Kent County Council, Diversity & Equality Team Room G37, Sessions House, County Hall, Maidstone, Kent, ME14 1XQ 2 Contents Responsibility for Waste Background Information 4 Roles of Authorities in Kent & Current Performance 5 Waste Segregation 6-17 Household Waste Recycling Centres 18-20 Conclusion 21 Waste Collection Authority Contacts 22 Quicklinks 23 Kent County Council Waste Management Mission Our Ambition is to deliver a high quality household waste disposal service, whilst remaining cost- effective for the people of Kent, with an emphasis on waste reduction, reuse, recycling and achieving zero landfill 3 Collection and disposal of waste Background Information Kent County Council (KCC) works in partnership with the Kent District and Borough Councils to find the best solution for the household waste that requires disposal. The aim of this document is to provide clear guidance to residents so they can dispose of their waste in a way that is in line with the Waste Hierarchy enabling waste to be reduced, reused or recycled where possible; and waste being sent for incineration or landfill is as minimal as possible. Prevention Most preferred Preparing for re-use Recycling Other recovery Disposal Least preferred 4 Roles of authorities in Kent District and Borough Councils are Waste Collection Authorities (WCAs) and they are responsible for collecting household waste from residents’ houses, referred to as kerbside collections. -

National Waste Report 2018 19 NOVEMBER 2018

National Waste Report 2018 19 NOVEMBER 2018 PREPARED FOR Department of the Environment and Energy PREPARED IN ASSOCIATION WITH Report title National Waste Report 2018 Client Department of the Environment and Energy Status Final Authors Joe Pickin, Paul Randell, Jenny Trinh, Bill Grant Data analysts Luke Richmond, Joe Pickin Reviewers Christine Wardle, Luke Richmond Project number P863 Report date 19 November 2018 Contract date 20 September 2017 Information current to 1 July 2018 Copyright Department of the Environment and Energy; Blue Environment Pty Ltd Disclaimer This report has been prepared for Department of the Environment and Energy in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment dated 20 September 2017, and is based on the assumptions and exclusions set out in our scope of work. Information in this document is current as of 1 July 2018. While all professional care has been undertaken in preparing this report, Blue Environment Pty Ltd cannot accept any responsibility for any use of or reliance on the contents of this report by any third party. The mention of any company, product or process in this report does not constitute or imply endorsement by Blue Environment Pty Ltd. © Department of the Environment and Energy; Blue Environment Pty Ltd Blue Environment prints on 100% recycled paper Blue Environment Pty Ltd ABN 78 118 663 997 Suite 209, 838 Collins St, Docklands Vic 3008 Email: [email protected] Web: www.blueenvironment.com.au Phone: +61 3 9081 0440 / +61 3 5426 3536 Contents At a glance .................................................................................................................................. -

Craven Recycling-Frequently Asked Questions

Craven County Curbside Recycling Program Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) Q: I have not received a recycling roll cart or I’m a new resident. How do I get a recycling roll cart? A: Please call Waste Industries dba GFL at 252-638-1366 to request a 95 gallon recycling roll cart. Q: What do the carts look like? A: The carts are 95 gallon lime green roll carts with lids and they are easily distinguishable from the old bins or trash bins. They are stamped with GFL which stands for Waste Industries dba Green for Life (GFL). The cart you receive will also have information stamped on the top in white lettering. The dimensions of the cart are 42 inches tall and 35 inches wide at the top. Q: What day will my new cart be serviced? A: Each cart will be delivered with a calendar with the weeks color coded. Your cart will have a colored decal with the day of the week notated. Look at your calendar to find your week and day according to the colored decal on your cart. For example, if you have a red decal with an M, then you are serviced on Mondays on the red weeks. Your cart will be serviced every four weeks. If you lose your calendar, please go to www.cravenrecycles.com and use the Recycling Pickup Schedule App to find your recycling dates. Carts should be placed curbside by 7:00 a.m. on collection day. Q: The sticker on my cart has faded and I cannot read it. -

FAQ for Recycle Right

FAQ For Recycle Right Why did the guidelines change for curbside recycling? Curbside recycling is facing a contamination crisis. Contamination is caused when people place materials in the recycling bin that do not belong. Recycling processors have a difficult time sorting out the trash, which makes its way into the sorted/bailed material that is sold to market. For a long time, China was the largest buyer of this material from the U.S. And because of increasing contamination levels, China made the decision to stop importing this material. This left the U.S. with an overabundance of recyclable commodities (re: bailed material) with a lot of trash mixed in. To address the contamination issue in Lancaster County, and ensure curbside recycling is sustainable, we went “back to the basics” with four material types that have a strong domestic market—meaning, there is a demand for this material by manufacturers in the U.S. We call these materials the “Big 4” and include: 1) corrugated cardboard (like shipping and packing boxes), 2) metal food and beverage cans, 3) plastic bottles and jugs with a neck, and 4) glass bottles and jars. Why are some materials allowed in the recycling bin, while others go to a drop-off location? In Lancaster County, we use a process called “single-stream” recycling, where residents can put all their approved recyclables into one bin. These materials are collected and taken to a materials recovery facility (MRF) where they are sorted, bailed, and sold to manufacturers, who turn them into new products. The sorting process is mostly automated, using various screens, magnets, and optical sorters to identify materials. -

Your Recycling and Refuse Service Standards

Your Recycling and Refuse Service Standards for Lewisham 1 What are Service Standards? Service Standards set out the standards that residents can expect from the Council regarding both recycling and refuse collection services. These services have a major impact, making Lewisham a great place to live, but we need your support and commitment. This is why the standards also outline what we need from you. Please visit www.lewisham.gov.uk/recycling for more information and keep this leaflet to refer to, thank you. Recycling We will provide a weekly collection of your paper, cardboard, glass, cans, plastic bottles, mixed plastics, beverage cartons (Tetra Pak) and shredded paper from your recycling wheelie bins, green boxes, clear sacks and large communal bins. Our promise Your role One of the following will be provided for Please contact us to let us know what kerbside properties and flats for recycling: recycling facilities you require. Recycling wheelie bins (kerbside). When recycling please ensure that you: Clear sacks (flats). Place the correct materials in the Communal recycling bins (estates/flats). recycling bin, loose if possible. Green reusable recycling estates bags Do not use black refuse sacks (these (estates). will not be collected). Your recycling crew will only empty recycling Wheelie bins and sacks must be bins and clear transparent sacks that contain moved to the inside edge of your the correct materials. property and be clear of obstructions. Leave recycling bins and clear sacks out by 6am on the correct collection day. 2 Our promise Your role We will return your recycling bin to the Please put the returned bin back to its outside edge of your property. -

Waste Management

10 Waste Management Coordinating Lead Authors: Jean Bogner (USA) Lead Authors: Mohammed Abdelrafie Ahmed (Sudan), Cristobal Diaz (Cuba), Andre Faaij (The Netherlands), Qingxian Gao (China), Seiji Hashimoto (Japan), Katarina Mareckova (Slovakia), Riitta Pipatti (Finland), Tianzhu Zhang (China) Contributing Authors: Luis Diaz (USA), Peter Kjeldsen (Denmark), Suvi Monni (Finland) Review Editors: Robert Gregory (UK), R.T.M. Sutamihardja (Indonesia) This chapter should be cited as: Bogner, J., M. Abdelrafie Ahmed, C. Diaz, A. Faaij, Q. Gao, S. Hashimoto, K. Mareckova, R. Pipatti, T. Zhang, Waste Management, In Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Waste Management Chapter 10 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................. 587 10.5 Policies and measures: waste management and climate ....................................................... 607 10.1 Introduction .................................................... 588 10.5.1 Reducing landfill CH4 emissions .......................607 10.2 Status of the waste management sector ..... 591 10.5.2 Incineration and other thermal processes for waste-to-energy ...............................................608 10.2.1 Waste generation ............................................591 10.5.3 Waste minimization, re-use and -

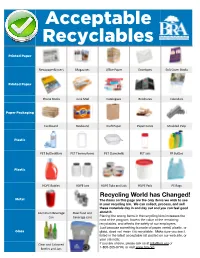

Acceptable Recyclables

Acceptable Recyclables Printed Paper Newspaper&insert Magazines Office Paper Envelopes So Cover Books Printed Paper Phone Books Junk Mail Catalogues Brochures Calendars Paper Packaging Cardboard Boxboard Kra9 Paper Paper Cores Moulded Pulp Plastic PET BoEles&Jars PET Thermoforms PET Clamshells PET Jars PP BoEles Plastic HDPE BoEles HDPE Jars HDPE Tubs and Lids HDPE Pails PE Bags Recycling World has Changed! Metal The items on this page are the only items we wish to see in your recycling bin. We can collect, process, and sell these materials day in and day out and you can feel good Aluminum Beverage Steel food and about it. Can beverage cans Placing the wrong items in the recycling bins increases the cost of the program, lowers the value of the remaining recyclables, and affects the safety of our employees. Just because something is made of paper, metal, plastic, or Glass glass, does not mean it is recyclable. Make sure you see it listed in the latest acceptable list posted on our web site, or your calendar. Clear and Coloured If you are unsure, please ask us at [email protected] or 1-800-265-9799, or visit www.bra.org BoEles and Jars Recent Program Changes While cartons are a defined commodity by the ISRI SpecificaQon circular, they are a laminated product that needs to be kept separate from other commodiQes otherwise they become a contaminaQon issue. Because of the shape shi9ing ability (2D vs 3D) this make Cartons them hard to separate even with the latest opQcal technology. Markets are not stable, price is low while handling costs are high. -

Encorp Pacific Presentation Overview

The BC EPR Model: A Leader in North America Allen Langdon President and CEO Encorp Pacific Presentation Overview • Overview of EPR IN BC • EPR for Packaging in BC • Overview of Encorp System • Benefits of EPR • Impact on Municipalities • What’s Next? Extended Producer Responsibility • Extended to what? – End-of-life (EOL) management of products and packaging • Responsible for what? – Collecting, recycling and diverting material from landfill – Paying the costs associated with activities set out in the a stewardship plan approved by the BC Ministry of Environment • Whose responsibility? – Producer—the business that provides the product of packaging to the BC residential consumer is responsible – Producer also known as the “steward” in some other provinces EPR is the law in BC • July 2004 – BC enacted Environmental Management Act (EMA) • October 2004 – BC filed Recycling Regulation • Product categories included as separate schedules under the regulation (beverage containers are Schedule 1) • There are now over 15 stewardship agencies in BC that manage materials such as paint, tires and electronics Packaging EPR in BC Encorp Pacific – 75.8% recovery rate (2017) • Schedule 1 – Beverage Containers (both residential and IC & I) Recycle BC – 75% recovery rate (2017) • Schedule 5 – Packaging and Paper Products (residential only) Overview of Encorp Pacific • Federally incorporated, not-for-profit corporation under the Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Act. • Used Beverage Container (UBC) management is our core business. Also a service provider to Electronic Products Recycling Association (EPRA) (2006) and Major Appliances Recycling Roundtable (MARR) (2018) • Five Members • Canadian Beverage Assn. (soft drinks), • Juice Council of BC, • Retail Council of Canada (grocery trade), • Canadian Bottled Water Assn., and • Beverage Alcohol Containers Mgmt. -

Good Practice Performance Measures for Kerbside Recycling Systems

Getting more from our recycling systems Good practice performance measures for kerbside recycling systems recycling systems Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) Published by Sustainability Programs Division Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) Level 2, 1 Fitzwilliam Street, Parramatta NSW 2150 PO Box 644, Parramatta NSW 2124 Phone: 02 8837 6000 Fax: 02 8837 6099 This publication was commissioned as a joint project by the NSW Government and Industry under the National Packaging Covenant. Disclaimer The Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) has made all reasonable efforts to ensure that the contents of this document are free from factual error. However, the Department shall not be liable for any damage or loss, which may occur in relation to any person taking action or not on the basis of this document. Acknowledgement The Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) and the NSW Jurisdictional Recycling Group wish to thank the following Councils for their participation in the research project: Ashfield, Auburn, Bankstown, Baulkham Hills, Blacktown, Botany Bay, Camden, Canterbury, Canada Bay (Drummoyne), Fairfield, Hornsby, Hurstville, Kogarah, Ku-ring-gai, Leichhardt, Liverpool, Manly, Marrickville, Parramatta, Penrith, Pittwater, Rockdale, Ryde, Sutherland, Warringah, Woollahra. ISBN: 1 920887 09 1 Copyright © Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW), February 2004 Contents Acronyms and glossary of terms ............................................................2 1 Introduction.....................................................................................3