Theories of International Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waltz's Theory of Theory

WALTZ’S THEORY OF THEORY 201 Waltz’s Theory of Theory Ole Wæver Abstract Waltz’s 1979 book, Theory of International Politics, is the most infl uential in the history of the discipline. It worked its effects to a large extent through raising the bar for what counted as theoretical work, in effect reshaping not only realism but rivals like liberalism and refl ectivism. Yet, ironically, there has been little attention paid to Waltz’s very explicit and original arguments about the nature of theory. This article explores and explicates Waltz’s theory of theory. Central attention is paid to his defi nition of theory as ‘a picture, mentally formed’ and to the radical anti-empiricism and anti-positivism of his position. Followers and critics alike have treated Waltzian neorealism as if it was at bottom a formal proposition about cause–effect relations. The extreme case of Waltz being so victorious in the discipline, and yet being so consistently misinterpreted on the question of theory, shows the power of a dominant philosophy of science in US IR, and thus the challenge facing any ambitious theorising. The article suggests a possible movement of fronts away from the ‘fourth debate’ between rationalism and refl ectivism towards one of theory against empiricism. To help this new agenda, the article introduces a key literature from the philosophy of science about the structure of theory, and particularly about the way even natural science uses theory very differently from the way IR’s mainstream thinks it does – and much more like the way Waltz wants his theory to be used. -

Analyzing Change in International Politics: the New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach

Analyzing Change in International Politics: The New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach - Guest Lecture - Peter J. Katzenstein* 90/10 This discussion paper was presented as a guest lecture at the MPI für Gesellschaftsforschung, Köln, on April 5, 1990 Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung Lothringer Str. 78 D-5000 Köln 1 Federal Republic of Germany MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Telephone 0221/ 336050 ISSN 0933-5668 Fax 0221/ 3360555 November 1990 * Prof. Peter J. Katzenstein, Cornell University, Department of Government, McGraw Hall, Ithaca, N.Y. 14853, USA 2 MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Abstract This paper argues that realism misinterprets change in the international system. Realism conceives of states as actors and international regimes as variables that affect national strategies. Alternatively, we can think of states as structures and regimes as part of the overall context in which interests are defined. States conceived as structures offer rich insights into the causes and consequences of international politics. And regimes conceived as a context in which interests are defined offer a broad perspective of the interaction between norms and interests in international politics. The paper concludes by suggesting that it may be time to forego an exclusive reliance on the Euro-centric, Western state system for the derivation of analytical categories. Instead we may benefit also from studying the historical experi- ence of Asian empires while developing analytical categories which may be useful for the analysis of current international developments. ***** In diesem Aufsatz wird argumentiert, daß der "realistische" Ansatz außenpo- litischer Theorie Wandel im internationalen System fehlinterpretiere. Dieser versteht Staaten als Akteure und internationale Regime als Variablen, die nationale Strategien beeinflussen. -

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

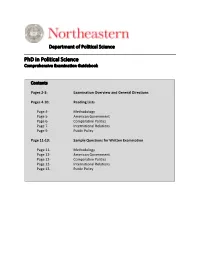

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Introduction to Political Science

Introduction to Political Science Professor Scott Williamson Fall 2021, Bocconi University e-mail: [email protected] Office hours: TBD Office: TBD Office room: TBD Class hours: TBD Class room: TBD Course Description What explains the rise of populism? How do authoritarian regimes hold onto power? Who opposes migration and why? When is the public more likely to hold political leaders accountable for poor governance? This course introduces the academic discipline of political science by exploring what its literatures have to say about these topics and others with substantive importance to global politics. We will read and discuss recent academic work utilizing a variety of methodological tools to answer these questions. In addition, the course is designed to help students navigate practical issues related to the effective conduct of political and social science research. We will review research practicalities ranging from choosing a research question to finding data and submitting articles to journals. Throughout the course, students will prepare a research proposal on a topic of their choice, which they will present to the class and submit in written format at the conclusion of the term. Course Objectives Throughout the course, students should expect: ▪ To develop knowledge about several major literatures in political science, gaining familiarity with ongoing debates and established findings. ▪ To acquire familiarity with a variety of primarily quantitative research methods used in political science and other social science disciplines. ▪ To develop understanding of how to consume and evaluate academic research, including how to recognize positive contributions, identify weaknesses, and provide constructive feedback in oral and written forms. -

Must War Find a Way?167

Richard K. Betts A Review Essay Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conict Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999 War is like love, it always nds a way. —Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage tephen Van Evera’s book revises half of a fteen-year-old dissertation that must be among the most cited in history. This volume is a major entry in academic security studies, and for some time it will stand beside only a few other modern works on causes of war that aspiring international relations theorists are expected to digest. Given that political science syllabi seldom assign works more than a generation old, it is even possible that for a while this book may edge ahead of the more general modern classics on the subject such as E.H. Carr’s masterful polemic, 1 The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and Kenneth Waltz’s Man, the State, and War. Richard K. Betts is Leo A. Shifrin Professor of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, Director of National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and editor of Conict after the Cold War: Arguments on Causes of War and Peace (New York: Longman, 1994). For comments on a previous draft the author thanks Stephen Biddle, Robert Jervis, and Jack Snyder. 1. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1946); and Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State, and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959). See also Waltz’s more general work, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and Hans J. -

Foreign Policy Analysis

FOREIGN POLICY ANALYSIS (listed in catalogue as Theoretical Explanations of Foreign Policy) Pol Sci 530 Jack S. Levy Rutgers University Spring 2014 Hickman 304 848/932-1073 [email protected] http://fas-polisci.rutgers.edu/levy/ Office Hours: after class and by appointment This seminar focuses on how states formulate and implement their foreign policies. Foreign Policy Analysis is a well-defined subfield within the International Relations field, with its own sections in the International Studies Association and American Political Science Association (Foreign Policy Analysis and Foreign Policy, respectively). Our orientation in this course is more theoretical and process-oriented than substantive or interpretive. We focus on policy inputs and the decision-making process rather than on policy outputs. An important assumption underlying this course is that the processes through which foreign policy is made have a considerable impact on the substantive content of policy. We follow a loose a levels-of-analysis framework to organize our survey of the theoretical literature on foreign policy. We examine rational state actor, bureaucratic/ organizational, institutional, societal, and psychological models. We look at the government decision-makers, organizations, political parties, private interests, social groups, and mass publics that have an impact on foreign policy. We analyze the various constraints within which each of these sets of actors must operate, the nature of their interactions with each other and with the society as a whole, and the processes and mechanisms through which they resolve their differences and formulate policy. Although most (but not all) of our reading is written by Americans and although much of it deals primarily with American foreign policy, most of these conceptual frameworks are much more general and not restricted to the United States. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma?

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma? Robert Jervis xploring whether the Cold War was a security dilemma illumi- nates botEh history and theoretical concepts. The core argument of the security dilemma is that, in the absence of a supranational authority that can enforce binding agreements, many of the steps pursued by states to bolster their secu- rity have the effect—often unintended and unforeseen—of making other states less secure. The anarchic nature of the international system imposes constraints on states’ behavior. Even if they can be certain that the current in- tentions of other states are benign, they can neither neglect the possibility that the others will become aggressive in the future nor credibly guarantee that they themselves will remain peaceful. But as each state seeks to be able to pro- tect itself, it is likely to gain the ability to menace others. When confronted by this seeming threat, other states will react by acquiring arms and alliances of their own and will come to see the rst state as hostile. In this way, the inter- action between states generates strife rather than merely revealing or accentuat- ing con icts stemming from differences over goals. Although other motives such as greed, glory, and honor come into play, much of international politics is ultimately driven by fear. When the security dilemma is at work, interna- tional politics can be seen as tragic in the sense that states may desire—or at least be willing to settle for—mutual security, but their own behavior puts this very goal further from their reach.1 1. -

Theories of International Relations* Ole R. Holsti

Theories of International Relations* Ole R. Holsti Universities and professional associations usually are organized in ways that tend to separate scholars in adjoining disciplines and perhaps even to promote stereotypes of each other and their scholarly endeavors. The seemingly natural areas of scholarly convergence between diplomatic historians and political scientists who focus on international relations have been underexploited, but there are also some signs that this may be changing. These include recent essays suggesting ways in which the two disciplines can contribute to each other; a number of prizewinning dissertations, later turned into books, by political scientists that effectively combine political science theories and historical materials; collaborative efforts among scholars in the two disciplines; interdisciplinary journals such as International Security that provide an outlet for historians and political scientists with common interests; and creation of a new section, “International History and Politics,” within the American Political Science Association.1 *The author has greatly benefited from helpful comments on earlier versions of this essay by Peter Feaver, Alexander George, Joseph Grieco, Michael Hogan, Kal Holsti, Bob Keohane, Timothy Lomperis, Roy Melbourne, James Rosenau, and Andrew Scott, and also from reading 1 K. J. Holsti, The Dividing Discipline: Hegemony and Diversity in International Theory (London, 1985). This essay is an effort to contribute further to an exchange of ideas between the two disciplines by describing some of the theories, approaches, and "models" political scientists have used in their research on international relations during recent decades. A brief essay cannot do justice to the entire range of theoretical approaches that may be found in the current literature, but perhaps those described here, when combined with citations of some representative works, will provide diplomatic historians with a useful, if sketchy, map showing some of the more prominent landmarks in a neighboring discipline. -

Paths to a Sound Governance of the World

Governance in a Changing World: Meeting the Challenges of Liberty, Legitimacy, Solidarity, and Subsidiarity Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, Extra Series 14, Vatican City 2013 www.pass.va/content/dam/scienzesociali/pdf/es14/es14-kuan.pdf Paths to a Sound Governance of the World HSIN-CHI KUAN Introduction In his paper “Accountability, Transparency, Legitimacy, Sustainable De- velopment and Governance”, Buttiglione takes governance as “the product or the activity of government” that is in turn defined as “a system of organs that govern a community”. This understanding is not very useful for our search for a better gover- nance of the world. It only suggests that the most distinct feature of gover- nance is the lack of a government. It remains uncertain whether the world is being “governed” by a system of organs that is however not qualified as a government. The distinction between government and governance ap- parently lies not in the activity. The activity of government varies radically from time to time and from country to country. In the past when govern- ment governed much less, the destiny of a people was also influenced by decisions that were not taken by their government authorities but by other domestic subjects whose actions were relevant to their welfare. This is, struc- turally speaking, the same kind of situation like what Buttiglione has de- scribed as of today, except that there are subjects acting from outside the affected country. In an indirect way, Buttiglione has attempted to clarify the difference between government and governance by reference to the erosion of state sovereignty. -

Realist Thought and the Future of American Security Policy

We encourage you to e-mail your comments to us at: [email protected]. The Past as Prologue Realist Thought and the Future of American Security Policy James Wood Forsyth Jr. Realism is dead, or so we are told. Indeed, events over the past 20 years tend to confirm the popular adage that “we are living in a whole new world.” And while some have proclaimed the death of power politics, it is worth remembering that we have heard this all before. Over the past 60 plus years, realism has enjoyed its time in the sun. Within the United States, realism initially arose during the interwar period in response to the perceived failures of Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s internationalism. By 1954, with the publication of the second edition of Hans Morgenthau’s Politics among Nations, those ideas had been discredited. During the 1970s, with gasoline shortages and a long, unsuccessful war in Vietnam tearing at America, the inadequacies of policy makers to properly frame world events led many to pursue other alternatives. Economic, political, and social changes led to the rise of topics such as transnational politics, international interdepen dence, and political economy, each of which allowed nonrealist perspec tives to carve out a substantial space for themselves. The dramatic ending of the Cold War—combined with the inability of policymakers to adequately explain, anticipate, or even imagine peaceful global change—ushered in a new round of thinking. Today many decision makers frame their policies around democracy, seeing it as the historical force driving the apparent peace among the world’s leading powers.