Inter-American System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fear Perception of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Peru

Electronic Journal of General Medicine 2021, 18(3), em285 e-ISSN: 2516-3507 https://www.ejgm.co.uk/ Original Article OPEN ACCESS Fear Perception of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Peru Christian R. Mejia 1*, J. Franco Rodriguez-Alarcon 2,3, Jean J. Vera-Gonzales 4, Vania L. Ponce-Lopez 5, Scherlli E. Chamorro-Espinoza 6, Alan Quispe-Sancho 7,8, Rahi K. Marticorena-Flores 6, Elizabeth S. Varela-Villanueva 6, Paolo Pedersini 9, Marcos Roberto Tovani-Palone 10** 1 Universidad Continental, Lima, PERU 2 Asociación Médica de Investigación y Servicios en Salud, Lima, PERU 3 Facultad de Medicina Humana, Universidad Ricardo Palma, Lima, PERU 4 Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal, Lima, PERU 5 Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Cajamarca, PERU 6 Universidad Nacional Hermilio Valdizán, Huánuco, PERU 7 Escuela Profesional de Medicina Humana, Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Cusco, PERU 8 ASOCIEMH CUSCO Asociación Científica de Estudiantes de Medicina Humana del Cusco, Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Cusco, PERU 9 IRCCS Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi, Milan, ITALY 10 Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, BRAZIL *Corresponding Author: [email protected] **Corresponding Author: [email protected] Citation: Mejia CR, Rodriguez-Alarcon JF, Vera-Gonzales JJ, Ponce-Lopez VL, Chamorro-Espinoza SE, Quispe-Sancho A, Marticorena-Flores RK, Varela-Villanueva ES, Pedersini P, Tovani-Palone MR. Fear Perception of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Peru. Electron J Gen Med. 2021;18(3):em285. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejgm/9764 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 10 Dec. 2020 Introduction: Fear is a natural response to something unknown. -

PATIENT INFORMATION Facility Name This Field Is Not Collected

SECTION III - PATIENT INFORMATION Facility Name (not a standard field in NAACCR Version 11.1) This field is not collected from you in each case record. Our data system assigns a reporting facility name to each record when uploaded. When sending cases to us on diskette or CD, include the facility name on each disk/CD label. This also helps us organize data storage. Reporting Facility Code NAACCR Version 11.1 field "Reporting Facility", Item 540, columns 382-391 This field should contain the ACoS/COC Facility Identification Number (FIN) for your facility, but the special code assigned to your facility by the MCR (usually four digits) is also acceptable if your data system can produce it (see next page for MCR codes). Facilities reporting on diskette or CD should include their MCR Code on each disk or CD label. (Records received from other central registries have this field zero-filled.) Example: Hospital A's registry may send its COC FIN ending with "148765" or its MCR Code "2102". The diskette label should include "2102". Formatted: Font: 10 pt NPI--Reporting Facility NAACCR Version 11.1 Item 545, columns 372-381 This code, assigned by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, is equivalent to the FIN Reporting Facility Code above for the MCR. This field is not required until 2008. Accession Number NAACCR Version 11.1 field "Accession Number--Hosp", Item 550, columns 402-410 This unique number identifies a patient at your facility based on when s/he was first accessioned onto your data system. The first four digits are the year in which the patient was first seen at your facility for the diagnosis and/or treatment of cancer, after your registry's reference date. -

North of Central America Situation. April 2019

FACT SHEET North of Central America Situation As of April 2019 Around 349,000 refugees and Between 2011 and 2018, the number The complex situation in the region is asylum-seekers from the North of of asylum claims has grown by compounded by internal displacement Central America (Honduras, El 970%, with 123,260 estimated during in Honduras and El Salvador, where Salvador and Guatemala) in the 2018, as compared to the 11,510 at least 174,000 and 71,500 world projected by end-2018. registered in 2011. respectively have been forced to flee by violence within their own countries. POPULATION OF CONCERN FUNDING (AS OF 30 APRIL 2019) Host Countries US$ 47 M USA* 293,900 requested for the NCA situation Honduras** 174,000 Funded El Salvador** 71,500 7% Mexico 26,800 3.2 M Spain 7,660 Italy 4,600 Canada 4,320 Costa Rica 3,690 Belize 3,300 Panama 1,730 Nicaragua 430 Guatemala 380 Unfunded Source: Based on data provided by governments to UNHCR. 93% * Projected data by end-2018 based on available data (up-to Dec for affirmative 43.8 M applications process and up-to Aug for defensive process). ** IDPs Overview In the North of Central America (NCA) tens of thousands of people have been forced into displacement by a confluence of factors that have led to an escalating situation of chronic violence and insecurity. These factors range from the influence of organized crime such as drug cartels and urban gangs, to the limited national capacity States to provide protection. UNHCR has expanded its presence and operational capacity in recent years to strengthen protection alternatives and encourage solutions for those affected, promote mechanisms to prevent and address situations of forced displacement and, together with other UN agencies, assist States to address the root causes of flight and promote a secure environment free from persecution, in line with their Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) undertakings. -

Lori Berenson Mejía V. Peru

Lori Berenson Mejía v. Peru 1 ABSTRACT This case involves the arrest, conviction, and detention of Lori Helene Berenson Mejía, a United States citizen charged with treason for her alleged affiliation with the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Forces. On November 30, 1995, she was arrested and on March 12, 1996, she was sentenced to life imprisonment, which was later annulled by the Supreme Council of Military Justice. She was confined in the Yanamayo Prison from January 17, 1996 to October 7, 1998 (2 years, 8 months and 20 days), and during this period was subjected to inhumane detention conditions. On August 28, 2000, a new proceeding against Ms. Berenson Mejía was commenced in the ordinary criminal jurisdiction. This trial culminated in the judgment of June 20, 2001, which found Ms. Berenson Mejía guilty of the crime of “collaboration with terrorism,” and sentenced her to 20 years imprisonment. The Supreme Court of Justice of Peru confirmed the judgment on February 13, 2002. The Court found that the State violated the American Convention on Human Rights. I. FACTS A. Chronology of Events November 13, 1969: Lori Berenson Mejía, a United States citizen, is born.2 1980-1994: Peru experiences serious social turmoil due to terrorism.3 1. Jennifer Toghian, Author; Amy Choe, Editor; Jenna Eyrich, Senior Editor; Elise Cossart-Daly, Chief IACHR Editor; Cesare Romano, Faculty Advisor. 2. Lori Berenson v. Peru, Merits, Reparations, and Costs, Judgment, Inter-Am. Ct. H.R. (ser. C) No. 119, ¶ 88.77 (Nov. 25, 2004). 3. Id. ¶ 88.1. 2609 2610 Loy. L.A. Int’l & Comp. -

How to Define a New Metropolitan Area? the Case of Quito, Ecuador, and Contributions for Urban Planning

land Article How to Define a New Metropolitan Area? The Case of Quito, Ecuador, and Contributions for Urban Planning Esthela Salazar 1,2,* , Cristián Henríquez 2,3 , Gustavo Durán 4, Jorge Qüense 2 and Fernando Puente-Sotomayor 5,6 1 Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra y la Construcción, Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas-ESPE, Sangolquí 171103, Ecuador 2 Instituto de Geografía, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Av. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Macul, Santiago 7820244, Chile; [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (J.Q.) 3 Researcher, Center for Sustainable Urban Development CEDEUS, El Comendador 1916, Providencia, Santiago 7820244, Chile 4 Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO, Diego de Almagro, Quito 170201, Ecuador; gduran@flacso.edu.ec 5 Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito 170521, Ecuador; [email protected] 6 LEMA, Urban and Environmental Engineering Department, Liège University, 4000 Liège, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Metropolitan Area of Quito has experienced exponential growth in recent decades, especially in peri-urban sectors. The literature has described this process as “urban sprawl”, a phenomenon that is changing the landscape by increasing land consumption and forming conurba- tions with the nearest populated centers. This article proposes a new, broader and more complex metropolitan structure for the metropolis of Quito, the linking of neighboring and conurbed areas to the form a new metropolitan area based on the case study of the Metropolitan District of Quito Citation: Salazar, E.; Henríquez, C.; Durán, G.; Qüense, J.; Puente- (DMQ). This new metropolitan area identification considers the interpretation of satellite images Sotomayor, F. -

Anastasia-Mejia-Letter-En.Pdf

Guatemala: 51 signatories call for authorities to drop criminal charges against Indigenous journalist Anastasia Mejía January 7, 2021 The undersigned individuals and organizations call on Guatemalan authorities to immediately drop all criminal charges against Indigenous Guatemalan radio journalist Anastasia Mejía Tiriquiz, who faces a criminal trial after being held in arbitrary pre-trial detention for more than a month. Guatemalan Civil Police arrested Mejía on September 22 for allegedly participating in an August 24 demonstration by a group of residents in the municipality of Joyabaj, Quiché, in central Guatemala. Mejía, a member of the Maya K’iche’ community and director of the radio station Xol Abaj Radio and Xol Abaj TV, had reported live on the events on Xol Abaj TV’s Facebook page. She faces charges of sedition and aggravated attack and was held at a detention center in Quetzaltenango for five weeks after her arrest, exposing her to the additional risk of contracting COVID-19 in the detention facility. Although Guatemalan law establishes that an initial hearing must take place within 24 hours after an individual is arrested, her hearing was set for October 8, more than two weeks after her arrest. A judge then pushed back the already-overdue hearing to October 28, to allow for “further investigation of evidence,” and leaving Mejía to spend more than a month in arbitrary pre-trial detention before even a preliminary hearing, putting her health at grave risk amid a global pandemic. On October 28, a judge released Mejía to house arrest after she paid a $2,500 bond, but ruled the criminal proceedings against her could move forward. -

Nationality Classification Using Name Embeddings

Nationality Classification Using Name Embeddings Junting Ye1, Shuchu Han4, Yifan Hu2, Baris Coskun3* , Meizhu Liu2, Hong Qin1, Steven Skiena1 1Stony Brook University, 2Yahoo! Research, 3Amazon AI, 4NEC Labs America fjuyye,shhan,qin,[email protected],fyifanhu,[email protected],[email protected] ABSTRACT Ethnicity Nationality (Lv1) Ritwik Kumar Ravi Kumar Ethnicity Nationality identication unlocks important demographic infor- Muthu Muthukrishnan Mohak Shah Black mation, with many applications in biomedical and sociological Deepak Agarwal White Ying Li research. Existing name-based nationality classiers use name sub- Lei Li API Jianyong Wang AIAN strings as features and are trained on small, unrepresentative sets Yan Liu Shipeng Yu 2PRACE of labeled names, typically extracted from Wikipedia. As a result, HangHang Tong Hispanic Aijun An these methods achieve limited performance and cannot support Qiaozhu Mei Jingrui He ne-grained classication. Xiaoguang Wang Tiger Zhang We exploit the phenomena of homophily in communication pat- Jing Gao Faisal Farooq Nationality (Lv1) terns to learn name embeddings, a new representation that encodes Rayid Ghani Usama Fayyad African gender, ethnicity, and nationality which is readily applicable to Leman Akoglu European Danai Koutra CelticEnglish building classiers and other systems. rough our analysis of 57M Evangelos Simoudis Evangelos Milios Greek Marko Grobelnik Jewish contact lists from a major Internet company, we are able to design a Tijl De Bie Claudia Perlich Muslim ne-grained nationality classier covering 39 groups representing Charles Elkan Nordic Diana Inkpen over 90% of the world population. In an evaluation against other Jennifer Neville EastAsian published systems over 13 common classes, our F1 score (0.795) is Derek Young SouthAsian Andrew Tomkins Hispanic Tina Eliassi-Rad substantial beer than our closest competitor Ethnea (0.580). -

Social Networks and Entrepreneurship. Evidence from a Historical

Social Networks and Entrepreneurship. Evidence from a Historical Episode of Industrialization Javier Mejia∗† New York University Abu Dhabi First version: June 2015 Current version: June 2018 Latest version: here Abstract This paper explores the relationship between social networks and entrepreneurship by con- structing a dynamic social network from archival records. The network corresponds to the elite of a society in transition to modernity, characterized by difficult geographical conditions, market failures, and weak state capacity, as in late 19th- and early 20th-century Antioquia (Colombia). With these data, I estimate how the decision to found industrial firms related to the position of individuals in the social network. I find that individuals more important bridging the network (i.e. with higher betweenness centrality) were more involved in industrial entrepreneurship. However, I do not find individuals with a denser network to be more involved in this type of activity. The rationale of these results is that industrial entrepreneurship was a highly-complex activity that required a wide variety of complementary resources. Networks operated as substitutes of markets in the acquisition of these resources. Thus, individuals with network positions that favored the combination of a broad set of resources had a comparative advantage in industrial entrepreneurship. I run several tests to prove this rationale. JEL Classification: O1, L1, L2, N8. ∗IamgratefultoAndr´esAlvarez,´ Esteban Nicolini, Elle Parslow, Elisa Salviato, Emanuele Colonnelli, Eric Quintane, Eun Seo Jo, Fabio S´anchez, Gavin Wright, In´es Cubillos, Isaias Chaves, Hernando Barahona, James Robinson, Jos´e Tessada, Joshua Kim, Juan Camilo Castillo, Juni Hoppe, Kevin DiPirro, Matthew O. Jackson, Mark Dincecco, Marcela Eslava, Melissa Dell, Leo Charles, Lionel Cottier, Santiago G´omez, Sebasti´an Otero, Stephen Haber, Timothy Guinnane, Tom Zohar, Tom´as Rodr´ıguez, Vivian Yu Zheng, Wilfried Kisling, and William Mej´ıa. -

The Economics of the Manila Galleon, Working Paper #0023

The Economics of the Manila Galleon Javier Mejia Working Paper # 0023 January 2019 Division of Social Science Working Paper Series New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island P.O Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, UAE https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/academics/divisions/social-science.html ∗ The Economics of the Manila Galleon Javier Mejia † Abstract The Manila Galleon was a commercial route that existed from 1565 to 1815. It connected Asia and America through the Pacific Ocean. It was a fundamental step in the history of globalization. The objective of this essay is to offer an economic framework to interpret the existing evidence on the Manila Galleon. Based on this framework, the essay identifies that the Manila Galleon was only possible thanks to the coincidence of a quite singular set of international circumstances and favorable market conditions at the local level. Additionally, the essay explores the experience of New Granada as a way to highlight the large asymmetry in the role and impact of the Manila Galleon trade across regions. JEL: D85; J13; O11; O14; O33; O41. Keywords: Manila Galleon; Trade History; Globalization; Silver; Philippines; Mex- ico; New Granada. ∗This essay was prepared for the Academic-Cultural Initiative of the Pacific Alliance, Philippines, and Spain Embassies in Bangkok, together with Thammasat University, UNESCO and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand, “Transpacific Connectivity through the Manila Galleon: Southeast Asia, the Pacific Coast of the Americas and Spain” †New York University Abu Dhabi. Email:[email protected]. Website:http://javiermejia.strikingly.com/ 1 1 Introduction The emergence of the Manila Galleon was an essential episode in trade history. -

Scientometric Analysis of Research on Socioemotional Wealth

sustainability Article Scientometric Analysis of Research on Socioemotional Wealth Luis Araya-Castillo 1 , Felipe Hernández-Perlines 2,* , Hugo Moraga 3 and Antonio Ariza-Montes 4 1 Facultad de Economía y Negocios, Universidad Andrés Bello, Santiago de Chile 7591538, Chile; [email protected] 2 Department of Business Administration, University of Castilla-La Mancha, 45071 Toledo, Spain 3 Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad Andrés Bello, Santiago de Chile 7591538, Chile; [email protected] 4 Social Matters Research Group, Universidad Loyola Andalucía, 14004 Córdoba, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-925268800 Abstract: Scientometric studies have become very important within the scientific environment in general, and in the family firm area in particular. This study aims at conducting a bibliometric analysis of socioemotional wealth within family firms. To this end, a background search of the terms family firm and socioemotional wealth has been carried out in the Web of Science, specifically in specialized journals published between 1975 and 2019 in the Science Citation Index. The resulting scientometric analyses are of the number of papers and citations, the main authors and journals, the WoS categories, the institutions, the countries and the word co-occurrence. One of the main conclusions of this paper is the abundance of studies that have been conducted on socioemotional wealth in family firms, which is reflected in the number of publications (501) and of citations of these studies (12,090). Another significant revelation is the copious number of authors, with Gómez-Mejía being the most relevant one and De Massis the one with the highest number of publications. -

Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control

Thursday, July 1, 2010 Part III Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control 31 CFR Chapter V Alphabetical Listing of Blocked Persons, Blocked Vessels, Specially Designated Nationals, Specially Designated Terrorists, Specially Designated Global Terrorists, Foreign Terrorist Organizations, and Specially Designated Narcotics Traffickers; Final Rule VerDate Mar<15>2010 16:15 Jun 30, 2010 Jkt 220001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\01JYR2.SGM 01JYR2 mstockstill on DSKH9S0YB1PROD with RULES2 38212 Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 126 / Thursday, July 1, 2010 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY persons, blocked vessels, specially Register and the most recent version of designated nationals, specially the SDN List posted on OFAC’s Web site Office of Foreign Assets Control designated terrorists, specially for updated information on designations designated global terrorists, foreign and blocking actions before engaging in 31 CFR Chapter V terrorist organizations, and specially transactions that may be prohibited by designated narcotics traffickers whose the economic sanctions programs Alphabetical Listing of Blocked property and interests in property are administered by OFAC. Please note that Persons, Blocked Vessels, Specially blocked pursuant to the various some OFAC sanctions programs prohibit Designated Nationals, Specially economic sanctions programs transactions involving persons and Designated Terrorists, Specially administered by the Department of the vessels not identified on Appendix A to Designated Global Terrorists, Foreign Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets 31 CFR chapter V or other lists provided Terrorist Organizations, and Specially Control (‘‘OFAC’’). OFAC is hereby by OFAC. Designated Narcotics Traffickers amending and republishing Appendix A This amendment reflects the names of AGENCY: Office of Foreign Assets in its entirety to include or delete, as persons and vessels identified on Control, Treasury. -

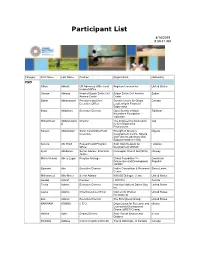

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana