July–September 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

PDF Download

THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF EMBRY-RIDDLE AERONAUTICAL UNIVERSITY FALL 2019 TERMINAL REINVENTION We take a look inside the airports of the future, as depots become destinations PAGE 12 Fall 2019 FROM THE PRESIDENT 8 22 Volume 15, No. 2 Lift, the alumni magazine of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, is published twice annually (spring and fall) by the division of In the fight for revenue, airports and Philanthropy & Alumni Engagement. airlines have promised us a more Copyright © 2019 Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University convenient, customized passenger Florida/Arizona/Worldwide 1 Aerospace Blvd. experience. Major airports are using Daytona Beach, FL 32114 All rights reserved. digital and automation technologies Senior Vice President of Philanthropy 6 10 to expedite baggage handling, and & Alumni Engagement Marc Archambault they are improving wayfinding Executive Director of Alumni Engagement Bill Thompson (’87) with digital displays and directions PHILANTHROPY & ALUMNI delivered to your smartphone. COMMUNICATIONS Executive Director of Communications Anthony Brown Increasingly, airports will use Wi-Fi ground operations: cargo, baggage, fuel, Senior Director of Communications/Editor Sara Withrow access points to identify optimal catering and de-icing. Assistant Director of Communications 12 locations for concessions, vending New designs will apply green materials Melanie Stawicki Azam machines and retailers. and energy-efficient options that create Assistant Director of Digital Engagement & Philanthropy IN OTHER WORDS ALUMNI @WORK There are -

Research Studies Series a History of the Civil Reserve

RESEARCH STUDIES SERIES A HISTORY OF THE CIVIL RESERVE AIR FLEET By Theodore Joseph Crackel Air Force History & Museums Program Washington, D.C., 1998 ii PREFACE This is the second in a series of research studies—historical works that were not published for various reasons. Yet, the material contained therein was deemed to be of enduring value to Air Force members and scholars. These works were minimally edited and printed in a limited edition to reach a small audience that may find them useful. We invite readers to provide feedback to the Air Force History and Museums Program. Dr. Theodore Joseph Crackel, completed this history in 1993, under contract to the Military Airlift Command History Office. Contract management was under the purview of the Center for Air Force History (now the Air Force History Support Office). MAC historian Dr. John Leland researched and wrote Chapter IX, "CRAF in Operation Desert Shield." Rooted in the late 1930s, the CRAF story revolved about two points: the military requirements and the economics of civil air transportation. Subsequently, the CRAF concept crept along for more than fifty years with little to show for the effort, except for a series of agreements and planning documents. The tortured route of defining and redefining of the concept forms the nucleus of the this history. Unremarkable as it appears, the process of coordination with other governmental agencies, the Congress, aviation organizations, and individual airlines was both necessary and unavoidable; there are lessons to be learned from this experience. Although this story appears terribly short on action, it is worth studying to understand how, when, and why the concept failed and finally succeeded. -

Federal Aviation Agency

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 30 • NUMBER 57 Thursday, March 25, 196S • Washington, D.C. Pages 3851-3921 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Atomic Energy Commission Civil Aeronautics Board Comptroller of the Currency Consumer and Marketing Service Economic Opportunity Office Engineers Corps Federal Aviation Agency Federal Maritime Commission Federal Power Commission Federal Trade Commission Fish and Wildlife Service Immigration and Naturalization Service Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau National Shipping Authority Securities and Exchange Commission Small Business Administration Veterans Administration Wage and Hour Division Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Subscriptions Now Being Accepted S L I P L A W S 89th Congress, 1st Session 1965 Separate prints of Public Laws, published immediately after enactment, with marginal annotations and legislative history references. Subscription Price: / $12.00 per Session Published by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 20402 i & S A Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on^ on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Regi . ^ ay0Iiai FEDERAL®REGISTER LI address Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mail adore ^ th0 Area Code 202 Phone 963-3261 fcy containe< -vwiTEo-WilTED’ nrcmvesArchives jsuuamg,Building, Washington, D.C. 20408), pursuant to tnethe authority coni Admin- Federal Register Act, approved July 26, 1935' (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.C., ch. 8B b under regulations prescribedIbed by thetne ent istrative Committee of the Federal Register, approved by the President (1 CFR Ch. -

Giving Agents the Edge TB 2510 2019 Cover Wrap Layout 1 22/10/2019 17:40 Page 2 TB 2510 2019 Cover Layout 1 22/10/2019 14:56 Page 1

TB 2510 2019 Cover Wrap_Layout 1 22/10/2019 17:40 Page 1 October 25 2019 | ISSUE NO 2,128 | travelbulletin.co.uk Giving agents the edge TB 2510 2019 Cover Wrap_Layout 1 22/10/2019 17:40 Page 2 TB 2510 2019 Cover_Layout 1 22/10/2019 14:56 Page 1 October 25 2019 | ISSUE NO 2,128 | travelbulletin.co.uk Giving agents the edge WORLD TRAVEL MARKET Special Preview Edition Cover pic : london.wtm.com S01 TB 2510 2019 Start_Layout 1 23/10/2019 10:33 Page 2 S01 TB 2510 2019 Start_Layout 1 22/10/2019 16:55 Page 3 OCTOBER 25 2019 | travelbulletin.co.uk NEWS BULLETIN 3 THIS WEEK UNINSURED ABROAD 70% of Brits are not sure whether their travel insurance covers them if Brexit happens, according to research by Holiday Extras. 04 NEWS News from the industry to help agents book more great holidays 08 AGENT INSIGHT Sandy Murray writes about luggage challenges 12 EVENT BULLETIN Brits should ensure that their travel insurance is up to date post-Brexit, to avoid disasters while abroad. All the action from our latest Airline Showcase in pictures A NATIONWIDE study The nation is becoming discovered in September conducted by Holiday Extras increasingly concerned that that almost three quarters of found that cancellation of the usually swift process Brits are unsure if their travel flights, ferries and trains to from a UK airport to a insurance covers them for the continent is a real holiday destination in Europe Brexit disruptions, and that concern for travellers ahead might be a thing of the past, the percentage of travellers 15 of Britain’s proposed exit with 29% of Brits fearing postponing or cancelling from the European Union, hectic passport queues. -

International Aviation: a United States Government-Industry Partnership

STANLEY B. ROSENFIELD* International Aviation: A United States Government-Industry Partnership I. Introduction In the last half of the 1970s, following the lead of deregulation legislation of domestic aviation, I United States international aviation policy was liber- alized to provide more competition and less regulation.2 The result of this policy has been an expanded number of U.S. airlines competing on interna- tional routes.3 It has also enlarged the number of U.S. international gate- ways and thus provided more points within the United States to and from 4 which to carry traffic. The U.S. has worked for bilateral agreements with foreign aviation part- ners which would provide more opportunity for all scheduled carriers, both U.S. and foreign, to expand routes and provide greater freedom to set fares and adjust capacity, based on the marketplace. The pro-competitive liberal policy advocated by the United States is based on the theory that competition will provide the lowest possible fares for the consumer, and that in open competition the U.S. carriers will not only survive, but also prosper. The policy has attracted criticism on the basis that implementation of the liberal policy has actually resulted in placing U.S. carriers in a less competi- tive position. Foreign airlines, the majority of which are government- owned, are instruments of foreign policy, which are not allowed to fail, *Mr. Rosenfield is a faculty Fellow with the U.S. Department of Transportation. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation. -

Sea King Salute P16 41 Air Mail Tim Ripley Looks at the Operational History of the Westland Sea King in UK Military Service

UK SEA KING SALUTE NEWS N N IO IO AT NEWS VI THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF FLIGHT Incorporating A AVIATION UK £4.50 FEBRUARY 2016 www.aviation-news.co.uk Low-cost NORWEGIAN Scandinavian Style AMBITIONS EXCLUSIVE FIREFIGHTING A-7 CORSAIR II BAe 146s & RJ85s LTV’s Bomb Truck Next-gen Airtankers SUKHOI SUPERJET Russia’s Rising Star 01_AN_FEB_16_UK.indd 1 05/01/2016 12:29 CONTENTS p20 FEATURES p11 REGULARS 20 Spain’s Multi-role Boeing 707s 04 Headlines Rodrigo Rodríguez Costa details the career of the Spanish Air Force’s Boeing 707s which have served 06 Civil News the country’s armed forces since the late 1980s. 11 Military News 26 BAe 146 & RJ85 Airtankers In North America and Australia, converted BAe 146 16 Preservation News and RJ85 airliners are being given a new lease of life working as airtankers – Frédéric Marsaly explains. 40 Flight Bag 32 Sea King Salute p16 41 Air Mail Tim Ripley looks at the operational history of the Westland Sea King in UK military service. 68 Airport Movements 42 Sukhoi Superjet – Russia’s 71 Air Base Movements Rising Star Aviation News Assistant Editor James Ronayne 74 Register Review pro les the Russian regional jet with global ambitions. 48 A-7 Corsair II – LTV’s Bomb Truck p74 A veteran of both the Vietnam con ict and the rst Gulf War, the Ling-Temco-Vought A-7 Corsair II packed a punch, as Patrick Boniface describes. 58 Norwegian Ambitions Aviation News Editor Dino Carrara examines the rapid expansion of low-cost carrier Norwegian and its growing long-haul network. -

Cooperative Agreements Involving Foreign Airlines: a Review of the Policy of the United States Civil Aeronautics Board Burton A

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 35 | Issue 4 Article 3 1969 Cooperative Agreements Involving Foreign Airlines: A Review of the Policy of the United States Civil Aeronautics Board Burton A. Landy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Burton A. Landy, Cooperative Agreements Involving Foreign Airlines: A Review of the Policy of the United States Civil Aeronautics Board, 35 J. Air L. & Com. 575 (1969) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol35/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. COOPERATIVE AGREEMENTS INVOLVING FOREIGN AIRLINES: A REVIEW OF THE POLICY OF THE UNITED STATES CIVIL AERONAUTICS BOARD* By BURTON A. LANDYt I. INTRODUCTION T RADITIONALLY, the airline industry has been highly individualistic. Today's air carriers, almost without exception, are the product of these individualistic pioneering efforts. Yet, during the current decade, there has been a notable trend "to band together" rather than the tradi- tional "go it alone" approach. A manifestation of this trend to join up was the merger movement of the early 1960's. This characteristic was due in large part to the poor financial condition of many of the airlines. As the jet transition took place and the financial health of the airlines improved, the merger wave subsided for a time, and the airlines seemed to return to their usual, independent way of doing business. -

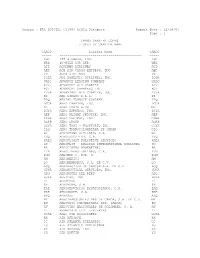

FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1

Source : FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1 CARGO CARRIER CODES LISTED BY CARRIER NAME CARCD Carrier Name CARCD ----- ------------------------------------------ ----- KHC 135 AIRWAYS, INC. KHC WRB 40-MILE AIR LTD. WRB ACD ACADEMY AIRLINES ACD AER ACE AIR CARGO EXPRESS, INC. AER VX ACES AIRLINES VX IQDA ADI DOMESTIC AIRLINES, INC. IQDA UALC ADVANCE LEASING COMPANY UALC ADV ADVANCED AIR CHARTER ADV ACI ADVANCED CHARTERS INT ACI YDVA ADVANTAGE AIR CHARTER, INC. YDVA EI AER LINGUS P.L.C. EI TPQ AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY TPQ DGCA AERO CHARTER, INC. DGCA ML AERO COSTA RICA ML DJYA AERO EXPRESS, INC. DJYA AEF AERO FLIGHT SERVICE, INC. AEF GSHA AERO FREIGHT, INC. GSHA AGRP AERO GROUP AGRP CGYA AERO TAXI - ROCKFORD, INC. CGYA CLQ AERO TRANSCOLOMBIANA DE CARGA CLQ G3 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES, S.A. G3 EVQ AEROEJECUTIVO, C.A. EVQ XAES AEROFLIGHT EXECUTIVE SERVICES XAES SU AEROFLOT - RUSSIAN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINES SU AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS AR LTN AEROLINEAS LATINAS, C.A. LTN ROM AEROMAR C. POR. A. ROM AM AEROMEXICO AM QO AEROMEXPRESS, S.A. DE C.V. QO ACQ AERONAUTICA DE CANCUN S.A. DE C.V. ACQ HUKA AERONAUTICAL SERVICES, INC. HUKA ADQ AERONAVES DEL PERU ADQ HJKA AEROPAK, INC. HJKA PL AEROPERU PL 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. 6P EAE AEROSERVICIOS ECUATORIANOS, C.A. EAE KRE AEROSUCRE, S.A. KRE ASQ AEROSUR ASQ MY AEROTRANSPORTES MAS DE CARGA, S.A. DE C.V. MY ZU AEROVAIS COLOMBIANAS LTD. (ARCA) ZU AV AEROVIAS NACIONALES DE COLOMBIA, S. A. AV ZL AFFRETAIR LTD. (PRIVATE) ZL UCAL AGRO AIR ASSOCIATES UCAL RK AIR AFRIQUE RK CC AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC CC LU AIR ATLANTIC DOMINICANA LU AX AIR AURORA, INC. -

CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 2 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: November 8, 2018

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2H CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 2 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: November 8, 2018 SUBJ: Contractions 1. Purpose of This Change. This change transmits revised pages to Federal Aviation Administration Order JO 7340.2H, Contractions. 2. Audience. This change applies to all Air Traffic Organization (ATO) personnel and anyone using ATO directives. 3. Where Can I Find This Change? This change is available on the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices. 4. Distribution. This change is available online and will be distributed electronically to all offices that subscribe to receive email notification/access to it through the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications. 5. Disposition of Transmittal. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. Page Control Chart. See the page control chart attachment. Original Signed By: Sharon Kurywchak Sharon Kurywchak Acting Director, Air Traffic Procedures Mission Support Services Air Traffic Organization Date: October 19, 2018 Distribution: Electronic Initiated By: AJV-0 Vice President, Mission Support Services 11/8/18 JO 7340.2H CHG 2 PAGE CONTROL CHART Change 2 REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−38............ 7/19/18 CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−18........... 11/8/18 3−1−1 through 3−4−1................... 7/19/18 3−1−1 through 3−4−1.................. 11/8/18 Page Control Chart i 11/8/18 JO 7340.2H CHG 2 CHANGES, ADDITIONS, AND MODIFICATIONS Chapter 3. ICAO AIRCRAFT COMPANY/TELEPHONY/THREE-LETTER DESIGNATOR AND U.S. -

AIRLIFT INTERNATIONAL INC. MIAMI International AIRPORT AVIATION 107

106 AVIATION Ae rial Vie w of Miami NEAREST TO Compliments Of AIRLIFT INTERNATIONAL INC. MIAMI INTERNATIONAl AIRPORT AVIATION 107 ACE•s AIR CARRIER ENGINE SERVICE. INC. A SUBSIDIARY OF FAIRCHILD HILLER P.O. Box 48-236, International Airport Miami, Florida 33148 Telephone: (305) 887-2666 Because ACES maintains a strict sense of professionalism , it 's work exceeds the specification s established by manufacturers and Federal agencies . Not only are its shops capable of detailed engine repa ir and over haul, but they ore fully diversified lor plating, tooling parts provisioning and testing of bore engines or full QEC con· figurations. ACES holds Certifi· Boe int737 cote 3604 awarded in 1946 by the Civil Aeronautics Adm ini s· !ration. In May 1967 the certifi· cote was extended by the Fed· eral Aviation Administration to cover Pratt & Whitney aircraft JTBD engines. Thars right! We never seem to get a wink of sleep. Our night· time schedules are planned just lor you so your cargo will be where you want it when you want it. In addition, since we are P.O. BOX. 48·535, INTERNATIONAL AIRPOR T BRANCH • MIAMI, FLOR IDA • PHONE 305·838·3671 AVIATION • AIR CARGO CARRIER 109 DIRECT AIR CARGO SCHEDULED FLIGHTS TO SAN SA LV ADOR ~ BLDG. C-3 MIAMI INTERNATIONAL AIRPOR T AEROLINEAS EL SALVADOR, S.A. P.O. BOX 48-1066, MIAMI MIAMI-TEL. 887-6471 NEW YORK - 5-E. 54th STREET NEW YORK-TEL 421-2456 110 AVIATION · AIR LINES ~AIR LINES~ • MIAMI, BARRANQUILLA BOGOTA, MEDELLIN, CALI, CARTAGENA, SAN ANDRES (ISLA) Passe nger Offi ce : CargoAnd General Office : 12 McA llister Arca de Bldg . -

The Decade That Terrorists Attacked Not Only the United States on American Soil, but Pilots’ Careers and Livelihoods

The decade that terrorists attacked not only the United States on American soil, but pilots’ careers and livelihoods. To commemorate ALPA’s 80th anniversary, Air Line Pilot features the following special section, which illustrates the challenges, opportunities, and trends of one of the most turbulent decades in the industry’s history. By chronicling moments that forever changed the aviation industry and its pilots, this Decade in Review—while not all-encompassing—reflects on where the Association and the industry are today while reiterating that ALPA’s strength and resilience will serve its members and the profession well in the years to come. June/July 2011 Air Line Pilot 13 The Decade— By the Numbers by John Perkinson, Staff Writer lthough the start of the millennium began with optimism, 2001 and the decade that followed has been infamously called by some “The Lost Decade.” And statistics don’t lie. ALPA’s Economic A and Financial Analysis (E&FA) Department dissected, by the numbers, the last 10 years of the airline industry, putting together a compelling story of inflation, consolidation, and even growth. Putting It in Perspective During the last decade, the average cost of a dozen large Grade A eggs jumped from 91 cents to $1.66, an increase of 82.4 percent. Yet the Air Transport Association (ATA) reports that the average domestic round-trip ticket cost just $1.81 more in 2010 than at the turn of the decade—$316.27 as compared to $314.46 in 2001 (excluding taxes). That’s an increase of just 0.6 percent more.