The Poles in the Seventeenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

The New Russia Ebook, Epub

THE NEW RUSSIA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mikhail Gorbachev | 400 pages | 27 May 2016 | Polity Press | 9781509503872 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The New Russia PDF Book Paul Johnson says:. Should there be a Second Cold War, human rights would become even more than, at present, a tool of cynical propaganda, especially if the bipartisan consensus regains the upper hand in U. This required him to manually transfer the computer's data to a separate hard drive, Mac Isaac said, which is how he came to see what some of the files contained. The Armenian prime minister accused Turkey of "transferring terrorist mercenaries" from Syria to Nagorno-Karabakh to fight for Azerbaijan. Trump responded with new attacks against the social media companies, saying in one tweet that it was, "so terrible that Facebook and Twitter took down the story" and claiming the articles were "only the beginning. Putin for human rights violations, authoritarian crackdowns and cyberattacks on the United States. Trump has called the treaty deeply flawed and refused a straight renewal, saying at first that China had to become a party to the agreement and then that the Russians had to freeze the weapons in their stockpile but not those deployed. Click here to leave a comment! And with the pandemic still raging in many areas around the world, it puts people in danger. The article also quotes the Ukrainian energy executive, in another alleged email, saying he was going to be sharing information with Amos Hochstein, who worked closely with Biden when he was Vice President as the special envoy and coordinator for international energy affairs. -

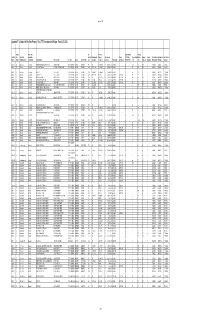

Appendix F-IFT

Appendix F-IFT Appendix F: All Industrial Facilities Property Tax (IFT) Exemptions in Michigan From 2001-2004 Project Project Site SIC Personal State Education Projected Certificate Site Project Site Community (Industry) Real Property Property Total Property Project Tax (0=None, Projected New Retained Projected Years of Date App Filed Date App. Filed Date of State Number Region Community Name Classification Company Name Project Location Local Unit County School District Code Investment Investment Investment Project Begin Completion 3=Half, 6= Full) Jobs Jobs Total Jobs Exemption With Locality With State Approval 2002-250 DT Detroit city Central City DAIMLER CHRYSLER CORPORATION 6700 LYNCH RD CITY OF DETROIT WAYNE DETROIT 3710 $0 $80,060,500 $ 80,060,500.00 12/1/2001 0 782 12 794 12 8/31/2001 9/9/2002 10/8/2002 2003-227 DT Detroit city Central City COCA- BOTTLING CO 5981 WEST WARREN AVENUE CITY OF DETROIT WAYNE DETROIT 2086 $3,559,900 $11,200,117 $ 14,760,017.00 1/2/2003 0 16 135 151 12 12/20/2002 7/30/2003 8/26/2003 2003-571 DT Detroit city Central City VITEC LLC 2627 CLARK ST CITY OF DETROIT WAYNE DETROIT 3714 $248,000 $11,304,000 $ 11,552,000.00 4/25/2003 3 10 20 30 12 5/30/2003 10/31/2003 11/25/2003 2001-440 DT Detroit city Central City IDEAL SHIELD 2525 CLARK AVE. CITY OF DETROIT WAYNE DETROIT 3449 $3,183,850 $65,850 $ 3,249,700.00 7/31/2000 12/15/2002 6 10 22 32 12 1/31/2001 10/22/2001 12/28/2001 2001-447 DT Detroit city Central City ARVIN MERITOR OE, LLC 6401 W FORT ST CITY OF DETROIT WAYNE DETROIT 3714 $0 $1,952,389 $ 1,952,389.00 10/1/2000 01/31/2001 6 106 0 106 12 5/2/2001 10/23/2001 12/28/2001 2001-509 DT Detroit city Central City GENERAL MILL SUPPLY CO. -

Documenta Polonica Ex Archivo Generali Hispaniae in Simancas

DOCUMENTA POLONICA EX ARCHIVO GENERALI HISPANIAE IN SIMANCAS Nova series Volumen I POLISH ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DOCUMENTA POLONICA EX ARCHIVO GENERALI HISPANIAE IN SIMANCAS Nova series Volumen I Edited by Ryszard Skowron in collaboration with Miguel Conde Pazos, Paweł Duda, Enrique Corredera Nilsson, Matylda Urjasz-Raczko Cracow 2015 Research financed by the Minister for Science and Higher Education through the National Programme for the Development of Humanities in 2012-2015 Editor Ryszard Skowron English Translation Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz Proofreading of Spanish Texts Cristóbal Sánchez Martos Proofreading of Latin Texts Krzysztof Pawłowski Design & DTP Renata Tomków © Copyright by Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences (PAU) & Ryszard Skowron ISBN 978-83-7676-233-3 Printed and Bound by PASAŻ, ul. Rydlówka 24, Kraków Introduction Between 1963 and 1970, as part of its series Elementa ad Fontiun Editiones, the Polish Historical Institute in Rome issued Documenta polonica ex Archivo Generali Hispaniae in Simancas, seven volumes of documents pertinent to the history of Poland edited by Rev. Walerian Meysztowicz.1 The collections in Simancas are not only important for understanding Polish-Spanish relations, but also very effectively illustrate Poland’s foreign policy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and the role the country played in the international arena. In this respect, the Spanish holdings are second only to the Vatican archives. In terms of the quality and quantity of information, not even the holdings of the Vienna archives illuminate Poland’s European politics on such a scale. Meysztowicz was well aware of this, opening his introduction (Introductio) to the first part of the publication with the sentence: “Res gestae Christianitatis sine Archivo Septimacensi cognosci vix possunt.”2 1 Elementa ad Fontium Editiones, vol. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Cognitive

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Cognitive Counterparts: The Literature of Eastern Europe’s Volatile Political Times, 1917-2017 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Teresa Constance Kuruc Committee in charge: Professor Amelia Glaser, Chair Professor Steven Cassedy Professor Sal Nicolazzo Professor Wm. Arctander O’Brien Professor Patrick Patterson 2018 Copyright Teresa Constance Kuruc All rights reserved The Dissertation of Teresa Constance Kuruc is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, my sister and brothers, and Scott for providing for me in every way during this process. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...........................................................................................................................iii Dedication ................................................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... -

The Following Are the Official Published Reports of the Engagement At

The following are the official published reports of the Engagement at Honey Springs, Indian Territory by Major General Blunt and the subordinate Federal commanders and by Brigadier General Cooper; unfortunately no reports from the subordinate Confederate officers were included in the official record. NO. 1 Report of Maj. Gen. James G. Blunt, U. S. Army, commanding District of the Frontier HEADQUARTERS DISTRICT OF THE FRONTIER, In the Field, Fort Blunt, C. N., July 26, 1863 GENERAL: I have the honor to report that, on my arrival here on the 11th instant, I found the Arkansas River swollen, and at once commenced the construction of boats to cross my troops. The rebels, under General Cooper (6,000), were posted on Elk Creek, 25 miles south of the Arkansas, on the Texas road, with strong outposts guarding every crossing of the river from behind rifle-pits. General Cabell, with 3,000 men, was expected to join him on the 17th, when they proposed attacking this place. I could not muster 3,000 effective men for a fight, but determined, if I could effect a crossing, to give them battle on the other side of the river. At midnight of the 15th, I took 250 cavalry and four pieces of light artillery, and marched up the Arkansas about 13 miles, drove their pickets from the opposite bank, and forded the river, taking the ammunition chests over in a flat-boat. I then passed down on the south side, expecting to get in the rear of their pickets at the mouth of the Grand River, opposite this post, and capture them, but they had learned of my approach and had fled. -

(National Peanut Board), 2005-2016

Description of document: Meeting minutes of the United States Peanut Board (National Peanut Board), 2005-2016 Requested date: 2016 Released date: 30-September-2016 Posted date: 17-October-2016 Source of document: USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service FOIA/PA Officer 1400 Independence Avenue, SW South Building, Rm. 3943 Stop 0202 Washington, DC 20250-0273 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. USDA Agricultural STOP 0202-Room 3943-S Marketing 1400 Independence Avenue, SW. -- Service Washington, DC 20250-0202 September 30, 2016 In reply, please refer to FOIA No. 2016-AMS-03647-F This is the final response the above referenced FOIA request which sought meeting minutes of the United States Peanut Board (National Peanut Board) from January 1, 2005 to May 3, 2016. -

… … Mushi Production

1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Mushi Production (ancien) † / 1961 – 1973 Tezuka Productions / 1968 – Group TAC † / 1968 – 2010 Satelight / 1995 – GoHands / 2008 – 8-Bit / 2008 – Diomédéa / 2005 – Sunrise / 1971 – Deen / 1975 – Studio Kuma / 1977 – Studio Matrix / 2000 – Studio Dub / 1983 – Studio Takuranke / 1987 – Studio Gazelle / 1993 – Bones / 1998 – Kinema Citrus / 2008 – Lay-Duce / 2013 – Manglobe † / 2002 – 2015 Studio Bridge / 2007 – Bandai Namco Pictures / 2015 – Madhouse / 1972 – Triangle Staff † / 1987 – 2000 Studio Palm / 1999 – A.C.G.T. / 2000 – Nomad / 2003 – Studio Chizu / 2011 – MAPPA / 2011 – Studio Uni / 1972 – Tsuchida Pro † / 1976 – 1986 Studio Hibari / 1979 – Larx Entertainment / 2006 – Project No.9 / 2009 – Lerche / 2011 – Studio Fantasia / 1983 – 2016 Chaos Project / 1995 – Studio Comet / 1986 – Nakamura Production / 1974 – Shaft / 1975 – Studio Live / 1976 – Mushi Production (nouveau) / 1977 – A.P.P.P. / 1984 – Imagin / 1992 – Kyoto Animation / 1985 – Animation Do / 2000 – Ordet / 2007 – Mushi production 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Tatsunoko Production / 1962 – Ashi Production >> Production Reed / 1975 – Studio Plum / 1996/97 (?) – Actas / 1998 – I Move (アイムーヴ) / 2000 – Kaname Prod. -

Cabinet BCH of Montana Natural Equine Care Clinic by Deena Shotzberger, President

Volume 26, Issue 3 www.bcha.org Summer 2015 Cabinet BCH of Montana Natural Equine Care Clinic By Deena Shotzberger, President BCHA Education Grants at Work in Montana Left: Cindy Brannon demonstrating a boot fit on Dr. Oedekoven’s horse, Sonny. Below: Jim Brannon discussing and trim- ming Jenny Holifield’s Arabian, John Henry. Thanks to a grant from the BCH ed to offer a more complete approach hoof’s role and function Education Foundation, Cabinet BCH to hoof care for consideration (regard- • Assessing the health of hooves hosted a clinic with Dr. Amanda Oede- less of whether animals were shod or • Why proper hoof care and koven, veterinarian; Jim Brannon, nat- barefoot). Many hoof problems can living conditions can lead to a longer ural hoof care practitioner; and Cindy be avoided by following better nutri- working life for your horse, and why Brannon, hoof boot specialist in Libby, tion, exercise and environment, and a this is critical in young growing horses MT on March 21. This was a great op- more holistic method of hoof care. The • The difference between a shoe- portunity for 23 equine owners in our clinic offered participants information ing trim and a barefoot trim and how small community to learn about nutri- on how to lower the risk for navicular, the differences improve the health of tion, exercise and environment; anato- laminitis, and insulin resistance. Par- your horses’ hooves my and function of the lower leg and ticipants learned how to provide their • How to spot and address im- hoofs; hoof care and trimming prin- horse a healthier and fitter life through balances in the hoof before they cause ciples. -

Kharkiv, EWJUS, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2020

Borderland City: Kharkiv Volodymyr Kravchenko University of Alberta Translated from Ukrainian by Marta Olynyk1 Abstract: The article attempts to identify Kharkiv’s place on the mental map of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, and traces the changing image of the city in Ukrainian and Russian narratives up to the end of the twentieth century. The author explores the role of Kharkiv in the symbolic reconfiguration of the Ukrainian-Russian borderland and describes how the interplay of imperial, national, and local contexts left an imprint on the city’s symbolic space. Keywords: Kharkiv, city, region, image, Ukraine, Russia, borderland. harkiv is the second largest city in Ukraine after Kyiv. Once (1920-34), K it even managed to replace the latter in its role of the capital of Ukraine. Having lost its metropolitan status, Kharkiv is now an important transport hub and a modern megapolis that boasts a greater number of universities and colleges than any other city in Ukraine. Strategically located on the route from Moscow to the Crimea, Kharkiv became the most influential component of the historical Ukrainian-Russian borderland, which has been a subject of symbolic and political reconfiguration and reinterpretation since the middle of the seventeenth century. These aspects of the city’s history have attracted the attention of numerous scholars (Bagalei and Miller; Iarmysh et al.; Masliichuk). Recent methodological “turns” in the humanities and social sciences shifted the focus of urban studies from the social reality to the city as an imagined social construct and to urban mythology and identity (Arnold; Emden et al.; Low; Nilsson; Westwood and Williams). -

Forest Vegetation of the Ukrainian Steppe Zone: Past and Present

ForestForestForest vegetationvegetationvegetation ofofof thethethe UkrainianUkrainian steppesteppe zone:zone:zone: pastpastpast andandand presentpresentpresent Parnikoza І. Institute of Molecular Biology and Genetics, NAS of Ukraine, Kyiv Ecological and Cultural Center Parni koza @gmail .com hhttp://pryroda.in.ua/step/. 1 Ukrainian steppe is part of the Eurasian steppe zone, which had formed before the end of Pleistocene Our steppe zone covers 40% of the country In the times of Kyiv Rus (XI-XIII cen.) it was called Nomads’ Fields and was boundless. During the XVI cen., it was called the Wild Fields Back in the geological past HoloceneTertiary: Miocene Pleistocene Intrazonal forests of the steppe zone ° Forests of Salix alba, Populus nigra, Acer platanoides, Quercus robur Forest area reduction in ancient times ° Ancient Greeks cut timber in Lower Dnieper floodplain forests near Olvia (modern Mykolaiv) Timber demand for fortification building since early times A.D. to the XVIII century The end of the ZaporozhyeZaporozhye society was also the end of the Steppe° However, in the XVII І century the Crimean Khagabate fell, Zaporozhye was dismissed and the Russian Empire began agricultural transformation of the steppe zone. ° Forestry, damming, melioration, and intensive grazing destroyed the native biota. The meliorative systems and artificial water reservoirs changed the climate and groundwater levels . 4 Today... ° Only 4% of the steppe zone that used to cover 40% of Ukrainian territory remain unploughed. Even so, of virgin steppe we now have only about 1%, mostly on steep slopes, along valleys, rocky areas where it cannot be exploited. ° These estimates need to be verified by complete inventory of steppe areas, which has not been done so far. -

La Causa Y La Cruza

newUniversityVOL. 4/NO. 13/NOVEMBER 12, 1971 To large numbers of laymenand clergy in California and across the nation the nameChrisHartmire has California Migrant Ministry become a household word. He is rarelydiscussed passively.To agri- business owners and the more con servative religious organizations in California. Hartmire is one of the most hated men in the church. But to many in the church today,both y cruza Catholic, to la and causa Protestant and la thousands of poverty-stricken farm workers, the California Migrant Ministry and the man who by marc grossman leads it representshopefor a better — "I've been making friends with the veteran of community projects in ganizing feeling the pressure future and signifies a new direction courageous to clergy for sixteenyears, especially Harlem and the Civil Rights Move- from some of the most they feel the church will have in CMM projects to keep touch with the the Migrant Ministry. ..Thechurch ment in the South where he was farm workers take if it is in pushed the Migrant Ministry to social realities of the 20th century. is the onegroup that isn't expecting arrested during the "Freedom Hartmire,director anythingfrom us. Allthe others, the Rides." Like all newly arrived prepare lor aneventual confronta- TheRev. Chris tion with theow nersof theagri-busi- of the California Migrant Ministry unions, the civil rights groups, they CMM personnel, Hartmire spent one of Cesar all want something in return for his first twomonths inthe state with ness establishment. and for. a decade Hartmire and his stalllearned that Chavez's closest friends and asso- their support.