Glossary of Watercolor Painting Terms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ARTIST's EYES a Resource for Students and Educators ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

THE ARTIST'S EYES A Resource for Students and Educators ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with great pleasure that the Bowers Museum presents this Resource Guide for Students and Educators with our goal to provide worldwide virtual access to the themes and artifacts that are found in the museum’s eight permanent exhibitions. There are a number of people deserving of special thanks who contributed to this extraordinary project. First, and most importantly, I would like to thank Victoria Gerard, Bowers’ Vice President of Programs and Collections, for her amazing leadership; and, the entire education and collections team, particularly Laura Belani, Mark Bustamante, Sasha Deming, Carmen Hernandez and Diane Navarro, for their important collaboration. Thank you to Pamela M. Pease, Ph.D., the Content Editor and Designer, for her vision in creating this guide. I am also grateful to the Bowers Museum Board of Governors and Staff for their continued hard work and support of our mission to enrich lives through the world’s finest arts and cultures. Please enjoy this interesting and enriching compendium with our compliments. Peter C. Keller, Ph.D. President Bowers Museum Cover Art Confirmation Class (San Juan Capistrano Mission), c. 1897 Fannie Eliza Duvall (1861-1934) Oil on canvas; 20 x 30 in. Bowers Museum 8214 Gift of Miss Vesta A. Olmstead and Miss Frances Campbell CALIFORNIA MODULE ONE: INTRO / FOCUS QUESTIONS 5 MODULE FOUR: GENRE PAINTING 29 Impressionism: Rebels and Realists 5 Cityscapes 30 Focus Questions 7 Featured Artist: Fannie Eliza Duvall 33 Timeline: -

Thematic Unit Nº12 Watercolour and Gouache. 12.1. 12.2. Definition. 12.3. a Brief History. 12.4. Aesthetic and Plastic Characte

PROCEDIMIENTOS Y TÉCNICAS PICTÓRICAS Antonio García López José Javier Armiñana Tormo THEMATIC UNIT Nº12 WATERCOLOUR AND GOUACHE. 12.1. DEFINITION. 12.2. A BRIEF HISTORY. 12.3. AESTHETIC AND PLASTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF WATERCOLOUR. 12.4. TYPES OF WATERCOLOUR. 12.5. TOOLS FOR WATERCOLOUR. 12.6. SUPPORTS FOR WATERCOLOUR. 12.7. WATERCOLOUR CONSERVATION. 12.8. WATERCOLOUR AND GOUACHE ELABORATION. 12.9. WATERCOLOUR APPLICATION: OVERLAPING LAYERS AND TRANSPARENCY. 12.10. PROPOUSED EXERCISES WITH WATERCOLOUR. 12.11. BIBLIOGRAPHY AND WEB LINKS. 1 PROCEDIMIENTOS Y TÉCNICAS PICTÓRICAS Antonio García López José Javier Armiñana Tormo 12.1. DEFINITION. The watercolour painting is defined as a mixture of pigments made from thin pigments and rubber that dissolved in water provides a very transparent colors. The foundation of watercolour lies on the clarity, cleanliness, brightness and luminosity of clear-cut colors, its transparency on the paper’s whiteness. Therefore it must be applied in aqueous light spots, its vehicle is water and the fluidity of it gives its main feature. The fund, usually paper, (also parchment, ivory, Crete funds, etc.) should be white and bright. If we compare the different existing techniques, we can say that watercolor has one of the first places in the degree of transparency and luminosity. Being a non-opaque material allows light to radiate both the support and of the previous strokes. This procedure provides a very useful experience and enhances the sensitivity to the use of fluid materials in other techniques. Because of its rapid implementation, your aesthetic goal shall be oriented consistently toward the achievement of graceful and sensitive works, not least out of a leaner and firm performance. -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

The Novel As Dutch Painting

one The Novel as Dutch Painting In a memorable review of Jane Austen’s Emma (1816), Walter Scott cele brated the novelist for her faithful representation of the familiar and the commonplace. Austen had, according to Scott, helped to perfect what was fundamentally a new kind of fiction: “the art of copying from nature as she really exists in the common walks of life.” Rather than “the splendid scenes of an imaginary world,” her novels presented the reader with “a correct and striking representation of that which [was] daily taking place around him.” Scott’s warm welcome of Emma has long been known to literary historians and fans of Austen alike. But what is less often remarked is the analogy to visual art with which he drove home the argument. In vividly conjuring up the “common incidents” of daily life, Austen’s novels also recalled for him “something of the merits of the Flemish school of painting. The subjects are not often elegant and certainly never grand; but they are finished up to nature, and with a precision which delights the reader.”1 Just what Flemish paintings did Scott have in mind? If it is hard to see much resemblance between an Austen novel and a van Eyck altarpiece or a mythological image by Rubens, it is not much easier to recognize the world of Emma in the tavern scenes and village festivals that constitute the typical subjects of an artist like David Teniers the Younger (figs. 1-1 and 1-2). Scott’s repeated insistence on the “ordinary” and the “common” in Austen’s art—as when he welcomes her scrupulous adherence to “common inci dents, and to such characters as occupy the ordinary walks of life,” or de scribes her narratives as “composed of such common occurrences as may have fallen under the observation of most folks”—strongly suggests that it is seventeenth-century genre painting of which he was thinking; and Teniers was by far the best known Flemish painter of such images.2 (He had in fact figured prominently in the first Old Master exhibit of Dutch and 1 2 chapter one Figure 1-1. -

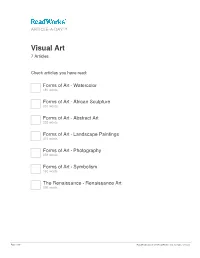

Visual Art 7 Articles

ARTICLE-A-DAY™ Visual Art 7 Articles Check articles you have read: Forms of Art - Watercolor 187 words Forms of Art - African Sculpture 201 words Forms of Art - Abstract Art 233 words Forms of Art - Landscape Paintings 315 words Forms of Art - Photography 258 words Forms of Art - Symbolism 165 words The Renaissance - Renaissance Art 266 words Page 1 of 9 ReadWorks.org · © 2016 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Forms of Art - Watercolor Forms of Art - Watercolor By ReadWo rks Watercolor painting is very popular among artists of all skill levels. Watercolor paint is hard in form. When water is added to it, the painter can apply the paint easily to paper. Thick types of paper are often used when watercolor painting. The thickness allows the water from the paint to be absorbed and not run or soak through the paper. Artists can control the intensity of watercolors by adding more or less water to the paint. The more water you put on your brush, the lighter the color will be. For darker colors, you should use only a little bit of water. Watercolor equipment is light and easy to use outdoors. The paintings also dry quickly. For these reasons, many artists use watercolor paint to make quick sketches or studies of nature. Believe it or not, water-based paint has been used since ancient times. Throughout the ages, artists have used water-based paint. Watercolor painting started to become popular in the mid- 1700s. Since then, artists have tried different papers and different water levels. Maybe you should take up watercolor painting and experiment with it. -

Eighteenth-Century Genre Painting

Eighteenth-Century Genre Painting ... At the end of the eighteenth century, Diderot identified genre painters indiscriminately as “those who busy themselves with only flowers, fruits, animals, woods, forests, mountains, as well as those who borrow their scenes from common or domestic life”. His definition referred to the diversity of themes treated by genre painters and also to the place occupied by their painting in the eighteenth-century scale of values. Considered inferior to history painting and religious painting, genre painting did nonetheless gain admiration from amateurs who, through their contact with Northern European art, were looking for less grandiloquent subjects. While Chardin held sway over the representation of everyday life with his intimist scenes tinged with a sense of interiority during the first half of the eighteenth century, Greuze (1725-1805) strove to bring fresh life to this genre by giving it a moralizing dimension in Room which the depiction of childhood, influenced by the philosophical spirit of the Enlightenment, Greuze was of supreme importance. Landscape painting, which belonged to the same genre, also enjoyed renewed interest during this period : under the aegis of Vernet and the link with Italy, ... artists were to reinvent classical landscapes painted on location. Neoclassicism Greuze and Moral Painting Trained under Charles Grandon, a painter from Lyon, Greuze settled in Paris around 1750 ; he bowed to Academy teaching with Natoire (1700-1777) without adhering to the official line and was accepted in 1755, the year that he presented Lazy Boy* to the Salon with its matching piece Young Knitter Asleep ... (fig.1). These works already revealed the particular care he pays to effects of matter – the texture of wood, silky hair – rendered through a limited palette of browns, white and russet inherited from the Dutch artists, Rembrandt in particular. -

The Workshop of Jacob De Wet (1610-1675) and His Mass Production of History Painting Angela Jager

The workshop of Jacob de Wet (1610-1675) and his mass production of history painting Angela Jager To cite this version: Angela Jager. The workshop of Jacob de Wet (1610-1675) and his mass production of history painting. Oud Holland, Brill Academic Publishers, 2018. hprints-02186635v2 HAL Id: hprints-02186635 https://hal-hprints.archives-ouvertes.fr/hprints-02186635v2 Submitted on 31 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Angela Jager, in: Oud Holland – Journal for Art of the Low Countries 131 (2018), vol. 2: pp. 67-108 The workshop of Jacob de Wet (1610-1675) and his mass production of history painting Over the course of his career, the history painter Jacob de Wet (I) (1610-1675) produced many paintings and trained lots of pupils. De Wet’s oeuvre almost exclusively consists of subjects from the Old and New Testament, and makes use of a recognizable format that favors simple compositions, numerous small-scale figures and clear narratives. A large number of unsigned paintings closely resemble De Wet’s compositions and figures. At auctions they are often attributed to De Wet or his circle. -

Chipgan: a Generative Adversarial Network for Chinese Ink Wash Painting Style Transfer

ChipGAN: A Generative Adversarial Network for Chinese Ink Wash Painting Style Transfer Bin He1, Feng Gao2, Daiqian Ma1;3, Boxin Shi1, Ling-Yu Duan1∗ National Engineering Lab for Video Technology, Peking University, Beijing, China1 The Future Lab, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China2 SECE of Shenzhen Graduate School, Peking University, Shenzhen, China3 [email protected],[email protected],{madaiqian,shiboxin,lingyu}@pku.edu.cn ABSTRACT Style transfer has been successfully applied on photos to gener- Gatys et al. ate realistic western paintings. However, because of the inherently Oli different painting techniques adopted by Chinese and western paint- C h ings, directly applying existing methods cannot generate satisfac- input photo I ip Generated Western Painting Real Western Painting nk G W A a N tory results for Chinese ink wash painting style transfer. This paper Gatys et al. Ink Wash sh proposes ChipGAN, an end-to-end Generative Adversarial Network based architecture for photo to Chinese ink wash painting style transfer. The core modules of ChipGAN enforce three constraints – voids, brush strokes, and ink wash tone and diffusion – to address three key techniques commonly adopted in Chinese ink wash paint- ing. We conduct stylization perceptual study to score the similarity Generated Ink Wash Painting Generated Ink Wash Painting Real Chinese Painting of generated paintings to real paintings by consulting with pro- Figure 1: Given an input photo, existing style transfer tech- fessional artists based on the newly built Chinese ink wash photo nique (Gatys et al. [11]) is able to generate western paint- and image dataset. The advantages in visual quality compared with ing with visually close style to the real painting (top row), state-of-the-art networks and high stylization perceptual study but not for the Chinese ink wash painting (bottom left). -

The Five Senses in Genre Paintings of the Dutch Golden Age

The Five Senses in Genre Paintings of the Dutch Golden Age Kitsirin Kitisakon+ (Thailand) Abstract This article aims to study one of the most popular themes in 17th-Century Dutch genre paintings - the five senses - in its forms and religious interpretations. Firstly, while two means of representation were used to clearly illustrate the subject, some genre scenes could also be read on a subtle level; this effectively means that such five senses images can be interpreted somewhere between clarity and am- biguity. Secondly, three distinct religious meanings were identified in these genre paintings. Vanity was associated with the theme because the pursuit of pleasure is futile, while sin was believed to be committed via sensory organs. As for the Parable of the Prodigal Son, party scenes alluding to the five senses can be read as relating to the episode of the son having spent all his fortune. Keywords: Five Senses, Genre Painting, Dutch Golden Age, Prodigal Son + Dr. Kitsirin Kitisakon, Lecturer, Visual Arts Dept., Faculty of Fine and Applied Art, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. The Five Senses… | 125 Introduction In the 16th and 17th Centuries, the five senses had never been more popular as subject matter for graphic art, especially in the Low Countries. Since Nordenfalk (1985), this theme has been occasionally discussed in monographs, catalogues of specific artists, or Dutch genre painting studies. Yet, an analysis of the modes of representation of the five senses seems to have been ignored, and there is a certain lack of fresh interest in their religious interpretations. From this observa- tion, this article aims to firstly examine how the five senses were represented in the Dutch genre paintings of the Golden Age, inspect how artists narrated them; secondly, reinvestigate how they can be religiously interpreted and propose deeper meanings which go beyond realistic appearance. -

Watercolor Resists by Caponi Art Park

Watercolor Resists By Caponi Art Park Project overview: Recommended for ages 5+ Much like a hidden message on a pirate’s treasure map, in this workshop, watercolors will reveal the picture that lays beneath the paint. Using their imaginations, participants will compose a picture using white crayon on white paper. The image they have created will only be revealed once watercolor paints have been applied to the entire image. You will have to wait and see what hidden treasure awaits! Supply list: ● Large sheet of white paper (We recommend using watercolor paper if you have it, but any thicker white paper will work. You can try standard printer paper, but with the wetness of the paints, it is not recommended. White construction paper would be great if you have it.) ● Paint brushes ( Any paintbrush will work. Even the foam brushes for painting walls will work. Use what you have on hand! We do recommend using a standard arts and crafts paintbrush.) ● Watercolor paints (Don’t have watercolor paints? Us tempera paint, and water it down. You can do this by putting a dime sized blob of tempera paint on a plate and mixing it with water until it runs really thin and more translucent.) ● White crayons (enough for the group to share) (If you don’t have white crayons, try a lightly colored crayon. It won’t “reveal the image” the same way, but it will still work. You can also try using white or cream colored candle wax.) ● Water cups for rinsing Instructions: ● Make sure each participant has a piece of watercolor paper, a brush, and a white crayon. -

Introduction to Watercolors for Field Sketching

Introduction to Watercolors for Field Sketching By Christine Elder This handout is a rough outline to accompany the video on watercolors that you can watch on your nature sketching course page: http://christineelder.com/nature-sketching-course. You may want to print it out and add notes as you watch the video. If you have watercolors, you may want to set them up and follow along! We will cover the basics of using the medium of watercolor, especially as its use pertains to casual field sketching, plus the basic materials and techniques to use in the field as well as exercises to practice at home in order to familiarize yourself with your paints. Let’s get going! Introduction • Value the process of discovering watercolors over the product; the joy of being outside, trusting that you are indeed learning more about your subject and your art materials and techniques than may be obvious from what’s shown on the paper, the hidden rewards which will slowly reveal themselves. You aren’t aiming for a botanical illustration or being the next Audubon so release any unrealistic expectations for yourself. • Characteristics of watercolors o Akin to cats – can be frustrating, have their own mind, can’t control them, but delightful all the same! o Transparent, so they can’t be modified extensively like one can do with opaque acrylics and oils, but they’re quick, non-toxic, easy to bring into the field, and will work well layering with other media. Watercolor supplies: • Portable watercolor palette, watercolor paper or field sketchbook, Pentel aquash watercolor brush, old oil brush, mechanical pencil, permanent pen, sponge, white gel pen and white colored pencil for highlights, waxy pencil or birthday candle for resist, rag, natural objects and photographs to practice with.