Introduction to Watercolors for Field Sketching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Gouache Painting' Materials List with Jim Minet

‘Gouache Painting’ Materials List With Jim Minet Here is my recommended list of the essential items you need for the very best watercolor experience. Brushes: Because gouache needs a slightly stiffer brush than regular watercolor, I recommend synthetic brushes. I do recommend Silver Brush short handle ‘Silver Silk 88’ brushes for gouache available at www.jerrysartarama.com and my second choice for gouache would be the short handle Silver White (by Silver Brush co) at Jerry’s or at www.dickblick.com Brush Type: A minimum of four watercolor brushes. 1. A large 1-inch flat wash brush (recommend – Silver White) 2. A medium-large ‘flat’ or ‘bright’ brush size 8 or 10 (recommend – Silver Silk 88) 3. A medium -small ‘flat’ or ‘bright’ brush size 4 or 6 (recommend- Silver Silk 88) 4. A round- brush size 4 (recommend Silver White) Paper – you can use either: • a glued block of 100 % Cotton 140 lb. cold or rough press watercolor paper, approximately 10x14 inch or larger. If it does not say ‘cotton’ then it is not. Or: • a couple large sheets of the same grade paper (this is a less expensive option that I recommend--sheets come in 22x30 inches. Cut it into 4 or 8 pieces) If you are not using a glued block, make sure to bring a drawing board to place your paper on. Any hard board, or inexpensive plastic or wood drawing board, not too large, will do, even a very firm piece of corrugated will do. Should not be too much bigger than the paper you will work on. -

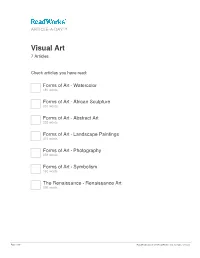

Visual Art 7 Articles

ARTICLE-A-DAY™ Visual Art 7 Articles Check articles you have read: Forms of Art - Watercolor 187 words Forms of Art - African Sculpture 201 words Forms of Art - Abstract Art 233 words Forms of Art - Landscape Paintings 315 words Forms of Art - Photography 258 words Forms of Art - Symbolism 165 words The Renaissance - Renaissance Art 266 words Page 1 of 9 ReadWorks.org · © 2016 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Forms of Art - Watercolor Forms of Art - Watercolor By ReadWo rks Watercolor painting is very popular among artists of all skill levels. Watercolor paint is hard in form. When water is added to it, the painter can apply the paint easily to paper. Thick types of paper are often used when watercolor painting. The thickness allows the water from the paint to be absorbed and not run or soak through the paper. Artists can control the intensity of watercolors by adding more or less water to the paint. The more water you put on your brush, the lighter the color will be. For darker colors, you should use only a little bit of water. Watercolor equipment is light and easy to use outdoors. The paintings also dry quickly. For these reasons, many artists use watercolor paint to make quick sketches or studies of nature. Believe it or not, water-based paint has been used since ancient times. Throughout the ages, artists have used water-based paint. Watercolor painting started to become popular in the mid- 1700s. Since then, artists have tried different papers and different water levels. Maybe you should take up watercolor painting and experiment with it. -

Certified Products List

THE ART & CREATIVE MATERIALS INSTITUTE, INC. Street Address: 1280 Main St., 2nd Floor Mailing Address: P.O. Box 479 Hanson, MA 02341 USA Tel. (781) 293-4100 Fax (781) 294-0808 www.acminet.org Certified Products List March 28, 2007 & ANSI Performance Standard Z356._X BUY PRODUCTS THAT BEAR THE ACMI SEALS Products Authorized to Bear the Seals of The Certification Program of THE ART & CREATIVE MATERIALS INSTITUTE, INC. Since 1940, The Art & Creative Materials Institute, Inc. (“ACMI”) has been evaluating and certifying art, craft, and other creative materials to ensure that they are properly labeled. This certification program is reviewed by ACMI’s Toxicological Advisory Board. Over the years, three certification seals had been developed: The CP (Certified Product) Seal, the AP (Approved Product) Seal, and the HL (Health Label) Seal. In 1998, ACMI made the decision to simplify its Seals and scale the number of Seals used down to two. Descriptions of these new Seals and the Seals they replace follow: New AP Seal: (replaces CP Non-Toxic, CP, AP Non-Toxic, AP, and HL (No Health Labeling Required). Products bearing the new AP (Approved Product) Seal of the Art & Creative Materials Institute, Inc. (ACMI) are certified in a program of toxicological evaluation by a medical expert to contain no materials in sufficient quantities to be toxic or injurious to humans or to cause acute or chronic health problems. These products are certified by ACMI to be labeled in accordance with the chronic hazard labeling standard, ASTM D 4236 and the U.S. Labeling of Hazardous NO HEALTH LABELING REQUIRED Art Materials Act (LHAMA) and there is no physical hazard as defined with 29 CFR Part 1910.1200 (c). -

Some Products in This Line Do Not Bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal

# Some products in this line do not bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Extra Strength School AP Glue Stick Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Gold Liner AP Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Silver Liner AP Adhesives, Glue New Port Sales, Inc. All Gloo CL Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Sparkler AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Xtreme School Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Craftbond All-Temp Hot AP Glue Sticks Adhesives, Glue Daler-Rowney Limited Rowney Rabbit Skin AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Decoupage Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2 Way Glue AP Squeeze & Roll Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. Kuretake Oyatto-Nori AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Chisel Tip Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Jumbo Tip Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Fine-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Wide-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts AP Ballpoint-Tip Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue STAMPIN' UP Stampin' Up 2 Way Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Creative Memories Creative Memories Precision AP Point Adhesive Adhesives, Glue Rich Art Color Co., Inc. Rich Art Washable Bits & Pieces AP Glitter Glue Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test One-Coat Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test Rubber Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. -

FA 361-Special Topics Drawing

Course Syllabus Fall 2015 Professor Avantika Bawa Office - 102 G E-mail: [email protected] Credits – 3 Meetings - M,W - 4.15-5.30 VMCC 107 . FA 361-Special Topics Drawing Course Description: In this course, students explore drawing within a contemporary art context. Using various techniques and media, students explore diverse and alternative facets of drawing. Exercises in alternative media and nontraditional approaches form the basis for project assignments. Critiques and discussions focused on media exploration encourage students to think in new ways about making art. Course Outcomes: The following course outcomes indicate competencies and measurable skills that students develop as a result of completing this course: At the end of this Course topics (and dates) that address these This outcome will be course, students learning outcomes are: evaluated primarily by should be able to: [assignment or activity]: Critique and grades on the assignment- Define, analyze, and Develop a refined understanding of the formal elements Project 2,3 solve problems. of drawing. Throughout the semester (Creative and critical thinking) Expand technical facility using various drawing mediums. Project 3, 4 &7 (Aug 24, 26, 31) Manipulate a variety of traditional and nontraditional materials to create a new context in which an idea is communicated. (Aug 24, 26, 31) Choose appropriate Use appropriate drawing terminology to objectively All Projects communication medium critique work. and technology. Throughout the semester All Projects (Communication) Demonstrate professional presentation skills and craftsmanship. Throughout the semester Implement well- Develop innovative drawing responses through All Projects designed search observation and execution. strategies. (Information Literacy) Demonstrate the ability to verbally critique your own work All Projects as well as that of others Throughout the semester Applying the concepts of Use sketchbooks as a drawing resource Project 4,5 &7 the general and Throughout the semester specialized studies to Develop fluency in drawing. -

Watercolor Resists by Caponi Art Park

Watercolor Resists By Caponi Art Park Project overview: Recommended for ages 5+ Much like a hidden message on a pirate’s treasure map, in this workshop, watercolors will reveal the picture that lays beneath the paint. Using their imaginations, participants will compose a picture using white crayon on white paper. The image they have created will only be revealed once watercolor paints have been applied to the entire image. You will have to wait and see what hidden treasure awaits! Supply list: ● Large sheet of white paper (We recommend using watercolor paper if you have it, but any thicker white paper will work. You can try standard printer paper, but with the wetness of the paints, it is not recommended. White construction paper would be great if you have it.) ● Paint brushes ( Any paintbrush will work. Even the foam brushes for painting walls will work. Use what you have on hand! We do recommend using a standard arts and crafts paintbrush.) ● Watercolor paints (Don’t have watercolor paints? Us tempera paint, and water it down. You can do this by putting a dime sized blob of tempera paint on a plate and mixing it with water until it runs really thin and more translucent.) ● White crayons (enough for the group to share) (If you don’t have white crayons, try a lightly colored crayon. It won’t “reveal the image” the same way, but it will still work. You can also try using white or cream colored candle wax.) ● Water cups for rinsing Instructions: ● Make sure each participant has a piece of watercolor paper, a brush, and a white crayon. -

Art Hazards List

ART AND CRAFT MATERIALS THAT CANNOT BE PURCHASED FOR USE IN KINDERGARTEN THROUGH 6TH GRADE Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment – California Environmental Protection Agency September 2016 California Education Code Section 32064 prohibits schools from purchasing art or craft materials containing a toxic substance for use by students in kindergarten and grades 1-6 (K- 6). The law also requires the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) to develop a list of products that schools cannot purchase for use by students in K-6. This list (attached) is intended to assist schools, school districts, and governing authorities of private schools in complying with the purchasing requirements. Purchasers must ensure that all art and craft materials to be used by students bear a statement of conformity to ASTM D-4236 (Standard Practice for Labeling Art Materials for Chronic Health Hazards), as required by federal law. Items to be used by students in K-6 must not bear acute or chronic health hazard labels. Although not required by law, avoiding art materials that bear acute or chronic health hazard labels when purchasing for grades 7-12 is a good precautionary measure. Schools are encouraged to inventory existing art and craft supplies and remove materials bearing health hazard labels from K-6th grade classrooms. For further information, please see Art and Craft Materials in Schools: Guidelines for Purchasing and Safe Use, accompanying this list or available online (see below). OEHHA compiled the attached list based on product evaluations conducted by other entities1 according to federal requirements. Other art and craft materials that can be listed are products recalled in the past five years2 (no such products are listed at this time), as well as those brought to OEHHA’s attention as bearing health hazard labels. -

ART225 Watercolor III

JEFFERSON COLLEGE COURSE SYLLABUS ART225 WATERCOLOR III 3 Credit Hours Prepared by: Blake Carroll Revised Date: January 2008 By: Blake Carroll Arts & Science Education Dr. Mindy Selsor, Dean ART225 Watercolor III I. COURSE DESCRIPTION A. Prerequisite: ART217 Watercolor II B. 3 Credit Hours C. Watercolor III is a studio art course allowing students to advance their study of the fine art of the transparent water-based media. Advanced theories and practices of watercolor will be studied, with students working with still-life, landscape, figure, abstract and non-objective concerns. Students will work extensively on developing personal imagery and discovering unique problem solutions. Types of pigment, paper, and methods of paint application will continue to be studied. Students will also learn about the history of the media in this course. This course will be open to both Fine Arts majors and non-majors as well, providing prerequisites have been met. II. EXPECTED LEARNING OUTCOMES/ASSESSMENT MEASURES This course is designed to give students an expanded knowledge and mastery of the history, theory and practice of Watercolor. Students will produce a wide variety of watercolor paintings emphasizing personal imagery and unique problem solutions, coming to understand the tremendous number of applications for this fine and commercial art media. Describe in-depth the history of watercolor Monitor student contributions to daily as an artist’s media discussions on the evolution of watercolor Intelligently analyze major artists and Group critique of -

Beginning & Intermediate Watercolor Painting

BEGINNING & INTERMEDIATE WATERCOLOR PAINTING Lampo Leong, PhD, Professor of Art Spring 2017 • Art 2510-01 (55436) & Art 3510-01 (55437) • MW 11am–1:50pm • Room A131 [email protected] • Office: A219 Fine Arts • Office Hours: MW 4:50pm–5:50pm https://missouri.instructure.com • http://www.artstor.org.proxy.mul.missouri.edu http://lampoleong.com • Course Description: This course introduces students to classical and contemporary watercolor painting techniques and concepts with emphasis on the understanding of its formal language and the fundamentals of artistic expression. Even though previous painting experience is not a prerequisite for this course, the vigorous training provided will prepare students for going into a professional fine art career. Painting from still-life, landscape, figure, and life models from observation will be geared towards realism; at the same time, various other watercolor painting styles could be explored. Color theory, linear perspective, compositional structure, figure/ground relationships, visual perception, spatial concepts, and critical thinking skills will all be emphasized extensively. We will also study and research major watercolor painting styles in historical context. The hope is that students will use this global approach to develop a “critical eye” in evaluation of contemporary watercolor painting. Demonstrations, videos, PowerPoint lectures, group and individual critiques will be given throughout the course. It may seem like a lot to absorb – but always remember that our main emphasis will be to encourage and nourish individuality and creativity. Course Objectives: § Introduce students to the fundamental processes of visual perception and artistic expression. § Develop students’ confidence in using watercolor painting as a primary medium for artistic expression. -

Watercolor Painting and the Outdoors Go Hand-In-Hand

Watercolor painting and the outdoors go hand-in-hand. This toolbox includes supplies and lesson plans to get you started observing and painting outside whether you are out exploring in the wilderness, the park down the street, or your front yard. ART OUTSIDE! SUMMER 2020 WHAT’S IN THIS TOOLBOX? Prang Watercolor Set Size 8, Round Sable Brush White Crayon Pocket Color Wheel Watercolor paper Jumbo Painting Postcard (send us your thoughts!) Art Lessons for all ages VOCABULARY Water Soluble: A substance that can be dissolved with water. Luminosity: Having a quality that appears to give off light. Transparency: Allowing light to pass through so that objects behind can be seen. Resist: something added to an artwork to create shapes and lines by protecting those parts during the next stages. The wax of the crayon will resist the paint and protect the white of the page. Pigment: The part of the paint that gives it color. Saturated: To be thoroughly soaked with liquid. In art, saturation can also refer to the intensity of color. AGES 5-7 Collect the Color Wheel Leaf Lines AGES 8-12 Collect the Color Scheme Shadow Shapes AGES 13+ ART LESSONS ART En Plein Air Phenology Wheels INTRODUCTION WHAT IS THE MACTIVITIES TOOLBOX? These lessons are designed as guided experiments with art making techniques that will help you learn new skills. While the theme of each toolbox will vary, you can expect to be challenged to look closer at your surroundings, learn about the ways artists solve problems, use your imagination, and develop your own sense of artistic style. -

Watercolor Supply List 2019

Watercolor Supply List 2019 Below I list supplies that I prefer, but you may bring anything and everything that you normally work with. I find that professional quality supplies generally yield the best results. Questions? Text or email me: 503-998-5833 or [email protected] ************Important! Bring a drawing or reference photo that you are willing to paint from more than once.******************* Paper: I use either 300 lb. Fabriano Uno Soft Press or 140 lb. Arches Cold or Hot Press. Bring what you like as long as it is 100% Rag. Brushes: I use an assortment of round & flat synthetic brushes, plus a 1” ‘Skipper’ brush (available from Cheap Joe’s Catalog - 1-800-227-2788) Here is a blog post about my favorite brushes: http://bit.ly/FavoriteBrushes Paints: Here are some of my favorites but bring what you like and use: Daniel Smith Holbein Winsor & Newton Quinacridone Gold Jaune Brilliant #1 Designer’s White Gouache Green Gold Cobalt Violet Light Cadmium Orange & Yellow Cobalt Blue Turquoise and Imidazolone Raw Sienna Yellow Quinacridone Violet or Magenta American Journey: Skip’s Green Ultramarine Blue Raw Umber American Journey: Sky Blue Winsor (Pthalo) Green and Permanent Rose Sennelier: French Vermillion M. Graham: Thioindigo Violet Brown Madder Quinacridone Miscellaneous Supplies • Large Water Container • Watercolor Pencils &/or W.C. • White High Flow Acrylic by Golden Crayons (I prefer Caran d’Ache • Cotton Rag (old diapers work well) brand) • Small Spray Bottle for water • Brush tip black marker such as Pitt • Palette artist pen or Tombow (Not Sharpies) • Artist’s Tape • Collage materials.. -

CONTINUING EDUCATION PROGRAMS ART Classes For

CONTINUING EDUCATION PROGRAMS ART ClASSES fOR ADUlTS AND hIGh SChOOl STUDENTS Fall 2017 Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts CONTINUING EDUCATION PROGRAMS CE PREVIEW NIGhT Join our community of dedicated artists of all ages and skill levels WEDNESDAy, SEPTEMbER 6 | 6 – 9 P.M. Interested in taking a class or trying something new, but don’t know where to start? Join us on Wednesday, September 6, for a free mini course and find out what PAFA CE has to offer! Experience hands-on instruction from expert CE faculty in PAFA’s studio classrooms. All courses are FREE with a $10 materials fee, with all materials provided! New students will receive a 10% discount on a Fall 2017 class.* Photo: Tom Crane Tom Photo: fOUNDED IN 1805 AS ThE NATION’S fIRST SChOOl AND MUSEUM Of fINE ARTS, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) promotes the transformative power of art and art making. For over 200 years, our close-knit community of faculty, critics, scholars, curators, museum professionals, and alumni have created a home for contemporary artists to reinvent tradition and make their own mark on the future. As part of this mission, PAFA Continuing Education (CE) programs offer a diverse array of studio art courses, workshops and programs for adults and high school students, open to all levels of ability, from absolute beginner through advanced artist. Whether you’ve never taken an art class before, are returning John horn after a long absence, or are preparing a portfolio for applying to art school, PAFA CE has something for you! ON ThE David Wiesner, illus.