Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Proquest Dissertations

The history of the conquest of Egypt, being a partial translation of Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam's "Futuh Misr" and an analysis of this translation Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hilloowala, Yasmin, 1969- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:08:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282810 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectiotiing the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Consumer Culture in Saudi Arabia

Consumer Culture in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Study among Heads of Household. Submitted by Theeb Mohammed Al Dossry to the University of Exeter as a Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology September 2012 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ……………………………………… 1 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my family especially: My father who taught me, how ambitious I should be, he is my inspiration for everything. My mother who surrounded me with her love, praying for me throughout the time I spent working on my thesis. To all my brother and sisters (Noura, Hoda, Nasser, Dr Mounera, Abdullah and Abdurrahman). With a special dedication to my lovely wife (Nawal) and my sons (Mohammed and Feras) 2 Abstract As Saudi Arabia turns towards modernisation, it faces many tensions and conflicts during that process. Consumerism is an extremely controversial subject in Saudi society. The purpose of this study was to investigate the changes that the opportunities and constraints of consumerism have brought about in the specific socio-economic and cultural settings between local traditions, religion, familial networks and institutions, on the one hand, and the global flow of money, goods, services and information, on the other. A qualitative method was applied. -

Is Islamic Law Influenced by the Roman Law?

Article Is Islamic Law Influenced by Kardan Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities the Roman Law? A Case 2 (1) 32–44 Study of International Law ©2019 Kardan University Kardan Publications Kabul, Afghanistan https://kardan.edu.af/Research/Curren tIssue.aspx?j=KJSSH *Zahid Jalaly Abstract Some Orientalists claim that Islamic law is a copy of Roman law or even that it is Roman law in an Islamic veil. This paper attempts to study international law of Islam and compare it with the international law notions of Roman law. It first evaluates claims of the Orientalists about the Islamic law in general and then compares International law of Islam with the Roman notions of international law. It concludes that, at least in the case of international law, Islamic law is not influenced by Roman Law because development, sources, literature or discourse related to and topics of siyar are distinct than the Roman jus gentium and jus fetiale. This indicates that siyar developed in a very different atmosphere and independently through reasoning of Muslim jurists and hence the two systems are independent of each other. Keywords: Islamic Law, Roman Law, International Law, Siyar, Jus Gentium, Jus Fetiale *Mr. Zahid Jalaly, Academic Administrator, Department of Political Science & International Relations, Kardan University, Kabul Afghanistan. 32 Is Islamic Law Influenced by the Roman Law? A Case Study of International Law Introduction The First Crusade1 was initiated in 1096 against the Muslim world and continued for more than a century.2 Mahmoud Shakir, an authority on Orientalism, asserts that Crusade, Evangelization3 and Orientalism4 were three institutions working in a parallel manner. -

Means of Proving Crime Between Sharia and Law

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 15, 2020 MEANS OF PROVING CRIME BETWEEN SHARIA AND LAW Enas Abdul Razzaq Ali Qutaiba Karim Salman [email protected] [email protected] Iraqi University ,College of Education for Girls - Department of Sharia Received: 14 March 2020 Revised and Accepted: 8 July 2020 Introduction Praise be to God, and may blessings and peace be upon the Messenger of God, his family, and his companions, and peace: A person has known crime since the dawn of humanity, beginning with Cain and Abel, where the first murder occurred in human history, and among the stories that tell us scenes of crime planning, the location of the crime, investigation, evidence, testimony, recognition, etc., According to what was mentioned in the Noble Qur’an about the story of our master Joseph (peace be upon him) in God Almighty’s saying: “We are shortening the best stories for you from what we have revealed to you this Qur’an. And stories mean succession in narration of events one after another, such as impactor, i.e. storytelling (tracing it to the end), because it contained all the arts of the story and its elements of suspense, photography of events and logical interconnectedness, as scholars say, for example: We find that the story began with a dream Or a vision that the Prophet of God Joseph (peace be upon him) saw and ended with the fulfillment and interpretation of that dream, and we see that the shirt of our master Joseph (peace be upon him) who was used as evidence for the innocence of his brothers -

History of International Law: Some

An Exploration of the ‘Global’ History of International Law: Some Perspectives from within the Islamic Legal Traditions Ayesha Shahid Chapter from: International Law and Islam - Historical Explorations (ISBN 978- 9004388284), edited by Ignaciao de la Rasilla and Ayesha Shahid Accepted manuscript PDF deposited in Coventry University’s Repository Publisher: Brill Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. 1 An Exploration of the ‘Global’ History of International Law: Some Perspectives from within the Islamic Legal Traditions Ayesha Shahid Abstract: In recent decades there has been a growing interest in global histories in many parts of the world. Exploring a ‘global history of international law’ is comparatively a recent phenomenon that has attracted the attention of international lawyers and historians. However most scholarly contributions that deal with the history of international law end-up in perpetuating Western Self- centrism and Euro-centrism. International law is often presented in the writings of international law scholars as a product of Western Christian states and applicable only between them. These scholars insist that the origins of modern (Post-Westphalian) international law lie in the state practice of the European nations of the sixteenth and seventeenth century. -

Islamic Law and Ambivalent Scholarship

Michigan Law Review Volume 100 Issue 6 2002 Islamic Law and Ambivalent Scholarship Khaled Abou El Fadl UCLA School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Khaled A. El Fadl, Islamic Law and Ambivalent Scholarship, 100 MICH. L. REV. 1421 (2002). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol100/iss6/11 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISLAMIC LAW AND AMBIVALENT SCHOLARSHIP Khaled Abou El Fad/* THE JUSTICE OF ISLAM: COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES ON ISLAMIC LA w AND SOCIETY. By Lawrence Rosen. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2000. Pp. 248. Cloth, $80; paper, $29.95. This book reminds me of the image of the arrogantly condescend ing and blustering tourist in Cairo who drifts into a store that has taken the trouble of prominently displaying the price of their com modities in nicely typed tags. Nevertheless, the tourist walks in, reads the price tag, and then proclaims, "Okay, what is the real price?" The poor store employee stares at him with incredulity, and simply repeats the price on the tag,· and, in response, the tourist emits this knowing and smug smile as if saying, "I know you guys, you never mean what you say; everything in Arab culture is negotiable, everything is subject to bargaining, and I will not be fooled." Of course, the tourist misses the point. -

ISIS in Iraq

i n s t i t u t e f o r i n t e g r at e d t r a n s i t i o n s The Limits of Punishment Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism iraq case study Mara Redlich Revkin May, 2018 After the Islamic State: Balancing Accountability and Reconciliation in Iraq About the Author Mara Redlich Revkin is a Ph.D. Candidate in Acknowledgements Political Science at Yale University and an Islamic The author thanks Elisabeth Wood, Oona Law & Civilization Research Fellow at Yale Law Hathaway, Ellen Lust, Jason Lyall, and Kristen School, from which she received her J.D. Her Kao for guidance on field research and survey research examines state-building, lawmaking, implementation; Mark Freeman, Siobhan O’Neil, and governance by armed groups with a current and Cale Salih for comments on an earlier focus on the case of the Islamic State. During draft; and Halan Ibrahim for excellent research the 2017-2018 academic year, she will be col- assistance in Iraq. lecting data for her dissertation in Turkey and Iraq supported by the U.S. Institute for Peace as Cover image a Jennings Randolph Peace Scholar. Mara is a iraq. Baghdad. 2016. The aftermath of an ISIS member of the New York State Bar Association bombing in the predominantly Shia neighborhood and is also working on research projects concern- of Karada in central Baghdad. © Paolo Pellegrin/ ing the legal status of civilians who have lived in Magnum Photos with support from the Pulitzer areas controlled and governed by terrorist groups. -

Hadith of Ghadir Al-Ghar

Opción, Año 35, Regular No.24 (2019): 1450-1459 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 Hadith of Ghadir Al-Ghar M.D. Fatima Kazem Shammam Faculty of Education of the human race, University of Muthanna, Iraq. Shammam. [email protected] Abstract The study aims to investigate the Hadith of Ghadir Al-Ghar via comparative qualitative research methods. As a result, The Hadith of al-Ghadir is a Mutawatir Hadith because it was narrated by 12000 narrators and such a large number did not occur except through the command of Allah Almighty. In conclusion, the day of Al-Ghadir is considered as a demarcation line between the people in the history of the Islamic nation after the Prophet, some of them believed in the Imam Ali's Wilayah over them, and some violated it. Keywords: Hadith, Ghadir, Al-Ghar, Islam, Imam. Hadith de Ghadir Al-Ghar Resumen El estudio tiene como objetivo investigar el Hadith de Ghadir Al-Ghar a través de métodos comparativos de investigación cualitativa. Como resultado, el Hadith de al-Ghadir es un Hadiz Mutawatir porque fue narrado por 12000 narradores y un número tan grande no ocurrió excepto por orden de Allah Todopoderoso. En conclusión, el día de Al-Ghadir se considera como una línea de demarcación entre las personas en la historia de la nación islámica después del Profeta, algunos de ellos creyeron en la Wilayah del Imam Ali sobre ellos y otros lo violaron. Palabras clave: Hadith, Ghadir, Al-Ghar, Islam, Imam. Recibido: 10-11-2018 •Aceptado: 10-03-2019 1451 M.D. Fatima Kazem Shammam Opción, Año 35, Regular No.24 (2019): 1450-1459 1. -

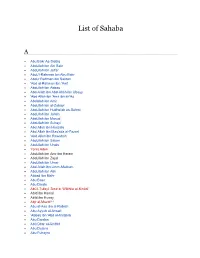

List of Sahaba

List of Sahaba A Abu Bakr As-Siddiq Abdullah ibn Abi Bakr Abdullah ibn Ja'far Abdu'l-Rahman ibn Abu Bakr Abdur Rahman ibn Sakran 'Abd al-Rahman ibn 'Awf Abdullah ibn Abbas Abd-Allah ibn Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy 'Abd Allah ibn 'Amr ibn al-'As Abdallah ibn Amir Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr Abdullah ibn Hudhafah as-Sahmi Abdullah ibn Jahsh Abdullah ibn Masud Abdullah ibn Suhayl Abd Allah ibn Hanzala Abd Allah ibn Mas'ada al-Fazari 'Abd Allah ibn Rawahah Abdullah ibn Salam Abdullah ibn Unais Yonis Aden Abdullah ibn Amr ibn Haram Abdullah ibn Zayd Abdullah ibn Umar Abd-Allah ibn Umm-Maktum Abdullah ibn Atik Abbad ibn Bishr Abu Basir Abu Darda Abū l-Ṭufayl ʿĀmir b. Wāthila al-Kinānī Abîd ibn Hamal Abîd ibn Hunay Abjr al-Muzni [ar] Abu al-Aas ibn al-Rabiah Abu Ayyub al-Ansari ‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib Abu Dardaa Abû Dhar al-Ghifârî Abu Dujana Abu Fuhayra Abu Hudhaifah ibn Mughirah Abu-Hudhayfah ibn Utbah Abu Hurairah Abu Jandal ibn Suhail Abu Lubaba ibn Abd al-Mundhir Abu Musa al-Ashari Abu Sa`id al-Khudri Abu Salama `Abd Allah ibn `Abd al-Asad Abu Sufyan ibn al-Harith Abu Sufyan ibn Harb Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah Abu Zama' al-Balaui Abzâ al-Khuzâ`î [ar] Adhayna ibn al-Hârith [ar] Adî ibn Hâtim at-Tâî Aflah ibn Abî Qays [ar] Ahmad ibn Hafs [ar] Ahmar Abu `Usayb [ar] Ahmar ibn Jazi [ar][1] Ahmar ibn Mazan ibn Aws [ar] Ahmar ibn Mu`awiya ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Qatan al-Hamdani [ar] Ahmar ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Suwa'i ibn `Adi [ar] Ahmar Mawla Umm Salama [ar] Ahnaf ibn Qais Ahyah ibn -

Islamic Law and Social Change

ISLAMIC LAW AND SOCIAL CHANGE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE INSTITUTIONALIZATION AND CODIFICATION OF ISLAMIC FAMILY LAW IN THE NATION-STATES EGYPT AND INDONESIA (1950-1995) Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Joko Mirwan Muslimin aus Bojonegoro (Indonesien) Hamburg 2005 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Rainer Carle 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Olaf Schumann Datum der Disputation: 2. Februar 2005 ii TABLE OF RESEARCH CONTENTS Title Islamic Law and Social Change: A Comparative Study of the Institutionalization and Codification of Islamic Family Law in the Nation-States Egypt and Indonesia (1950-1995) Introduction Concepts, Outline and Background (3) Chapter I Islam in the Egyptian Social Context A. State and Islamic Political Activism: Before and After Independence (p. 49) B. Social Challenge, Public Discourse and Islamic Intellectualism (p. 58) C. The History of Islamic Law in Egypt (p. 75) D. The Politics of Law in Egypt (p. 82) Chapter II Islam in the Indonesian Social Context A. Towards Islamization: Process of Syncretism and Acculturation (p. 97) B. The Roots of Modern Islamic Thought (p. 102) C. State and Islamic Political Activism: the Formation of the National Ideology (p. 110) D. The History of Islamic Law in Indonesia (p. 123) E. The Politics of Law in Indonesia (p. 126) Comparative Analysis on Islam in the Egyptian and Indonesian Social Context: Differences and Similarities (p. 132) iii Chapter III Institutionalization of Islamic Family Law: Egyptian Civil Court and Indonesian Islamic Court A. The History and Development of Egyptian Civil Court (p. 151) B. Basic Principles and Operational System of Egyptian Civil Court (p. -

Iraq Tribal Study – Al-Anbar Governorate: the Albu Fahd Tribe

Iraq Tribal Study AL-ANBAR GOVERNORATE ALBU FAHD TRIBE ALBU MAHAL TRIBE ALBU ISSA TRIBE GLOBAL GLOBAL RESOURCES RISK GROUP This Page Intentionally Left Blank Iraq Tribal Study Iraq Tribal Study – Al-Anbar Governorate: The Albu Fahd Tribe, The Albu Mahal Tribe and the Albu Issa Tribe Study Director and Primary Researcher: Lin Todd Contributing Researchers: W. Patrick Lang, Jr., Colonel, US Army (Retired) R. Alan King Andrea V. Jackson Montgomery McFate, PhD Ahmed S. Hashim, PhD Jeremy S. Harrington Research and Writing Completed: June 18, 2006 Study Conducted Under Contract with the Department of Defense. i Iraq Tribal Study This Page Intentionally Left Blank ii Iraq Tribal Study Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER ONE. Introduction 1-1 CHAPTER TWO. Common Historical Characteristics and Aspects of the Tribes of Iraq and al-Anbar Governorate 2-1 • Key Characteristics of Sunni Arab Identity 2-3 • Arab Ethnicity 2-3 – The Impact of the Arabic Language 2-4 – Arabism 2-5 – Authority in Contemporary Iraq 2-8 • Islam 2-9 – Islam and the State 2-9 – Role of Islam in Politics 2-10 – Islam and Legitimacy 2-11 – Sunni Islam 2-12 – Sunni Islam Madhabs (Schools of Law) 2-13 – Hanafi School 2-13 – Maliki School 2-14 – Shafii School 2-15 – Hanbali School 2-15 – Sunni Islam in Iraq 2-16 – Extremist Forms of Sunni Islam 2-17 – Wahhabism 2-17 – Salafism 2-19 – Takfirism 2-22 – Sunni and Shia Differences 2-23 – Islam and Arabism 2-24 – Role of Islam in Government and Politics in Iraq 2-25 – Women in Islam 2-26 – Piety 2-29 – Fatalism 2-31 – Social Justice 2-31 – Quranic Treatment of Warfare vs.