Disaster Mitigation Information in Football Matches: Fans Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bab Iii Penutup

BAB III PENUTUP Setelah menelaah bab-bab sebelumnya, yaitu Bab I dan II dalam skripsi ini, maka sampailah pada Bab III yakni Penutup, yang berupa kesimpulan dan saran. Adapun kesimpulan dan saran penulis adalah untuk menjawab masalah yang telah diuraikan dalam skripsi ini. A. Kesimpulan 1. Perjanjian kerja antara pihak klub sepak bola dengan pemain sepak bola harus memenuhi syarat sahnya perjanjian sebagaimana diatur dalam Pasal 1320 KUH Perdata. Perjanjian kerja yang dibuat dengan sah dan telah disepakati oleh para pihak, berlaku sebagai undang-undang bagi mereka yang membuatnya, hal tersebut sesuai dengan Pasal 1338 KUH Perdata. Dengan demikian, perlindungan hukum terhadap pemain sepak bola atas perjanjian kerja dengan klub sepak bola, terdapat pada perjanjian kerja yang dibuat atau yang telah disepakati. Tentang permasalahan gaji pemain sepak bola yang belum dibayar pada perjanjian kerja antara pemain sepak bola dengan pihak klub sepak bola PSIM ini sudah tidak sesuai dengan syarat-syarat perjanjian kerja waktu tertentu tentang gaji dalam pasal 59 Undang-Undang No. 13 Tahun 2003 Tentang Ketenagakerjaan. Oleh karena itu pihak klub sepak bola PSIM Yogyakarta telah melakukan wanprestasi 39 40 dan penyelesaiannya dapat dilakukan dengan musyawarah antar para pihak, jika dengan cara musyawarah tetap tidak menemukan titik temu maka penyelesaiannya akan di serahkan ke PSSI. Terkait dengan Perjanjian Kerja PSIM LIGA SUPER INDONESIA 2010-2011 Pasal 11 ayat 6 ” Perjanjian ini tidak dapat diakhiri pada saat berjalannya Musim Kompetisi dan/atau Turnamen yang sedang berjalan”, klausula tersebut sangat merugikan bagi pemain yang menderita cedera fisik permanen. Tidak mampu untuk bermain sepak bola lagi, mendapat kompensasi ganti rugi untuk 2 bulan gaji saja. -

Ponuda 2017-08-26 Prvi Deo.Xlsx

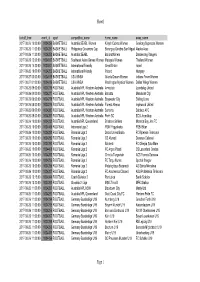

Sheet1 kickoff_time event_id sport competition_name home_name away_name 2017-08-26 10:00:00 1004256 BASKETBALL Australia SEABL Women Kilsyth Cobras Women Geelong Supercats Women 2017-08-26 11:00:00 1004257 BASKETBALL Philippines Governors Cup Barangay Ginebra San Miguel Alaska Aces 2017-08-26 11:30:00 1004258 BASKETBALL Australia SEABL Ballarat Miners Dandenong Rangers 2017-08-26 12:00:00 1004617 BASKETBALL Southeast Asian Games Women Malaysia Women Thailand Women 2017-08-26 15:30:00 1004847 BASKETBALL International Friendly Great Britain Israel 2017-08-26 18:00:00 1004259 BASKETBALL International Friendly Poland Hungary 2017-08-27 00:00:00 1004618 BASKETBALL USA WNBA Atlanta Dream Women Indiana Fever Women 2017-08-27 01:00:00 1004619 BASKETBALL USA WNBA Washington Mystics Women Dallas Wings Women 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004276 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Armadale Joondalup United 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004277 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Balcatta Mandurah City 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004278 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Bayswater City Stirling Lions 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004279 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Floreat Athena Inglewood United 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004280 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Sorrento Subiaco AFC 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004281 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Perth SC ECU Joondalup 2017-08-26 10:00:00 1004282 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Queensland Brisbane Strikers Moreton Bay Jets FC 2017-08-26 10:00:00 1004466 FOOTBALL Indonesia Liga 2 PSIM Yogyakarta PSBI Blitar -

Solidaritas Anarkisme Suporter Bola PSIM DAN PSS Tera Puspita Werdiyanti Prodi Sosiologi, Universitas Wisya Mataram E-Mail : [email protected]

Jurnal Populika Volume 7, Nomor 2, Juli 2019 Solidaritas Anarkisme Suporter Bola PSIM DAN PSS Tera Puspita Werdiyanti Prodi Sosiologi, Universitas Wisya Mataram E-mail : [email protected] As Martadani Noor Prodi Sosiologi, Universitas Wisya Mataram E-mail : [email protected] Paharizal Prodi Sosiologi, Universitas Wisya Mataram E-mail : [email protected] Abstract This research is located in Sleman, Yogyakarta. This research was conducted when researcher saw the solidarity of anarchism of football supporters. Factors related to the solidarity of anarchism of football supporters and the empowerment of football supporters, especially with PSIM and PSS. This research wants to describe more clearly how the solidarity of anarchism is, the factors associated with solidarity of anarchism and the empowerment of suporter in PSIM and PSS football clubs. This research was conducted with a qualitative descriptive research method. Data was collected by Snow Ball sampling until the data was at its saturation point. This method was chosen because the number of actors is large so it could gets more accurate data. The results obtained in the solidarity of football supporters anarchism prove that there are improvements from the supporters. Then the factors related to the solidarity of anarchism are still trying to become supporters who are more loved by the community and the empowerment of PSIM and PSS football supporters has not received training from any party. Keywords : Anarchisme Solidarity, Football Fans, PSIM and PSS. Pendahuluan. lebih lanjut dari legalisasi komunitas Sepak bola adalah olahraga yang pendukung suatu kesebelasan. Oleh karena cukup populer dan digemari di seluruh itu, munculah fanatisme dalam perilaku dunia. -

Psychological Characteristics of PSIM Yogykarta Players in Wading the League 2 Soccer Competition in 2019/2020

62 QUALITY IN SPORT 3 (5) 2019, p. 62-68, e-ISSN 2450-3118 Received 24.08.2019, Accepted 27.10.2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/QS.2019.018 Antonius Tri Wibowo1, Asna Syafitri2, Dody Tri Iwandana3 Mercu Buana University Yogyakarta Psychological characteristics of PSIM Yogykarta players in wading the League 2 soccer competition in 2019/2020 Abstract This study aims to determine the psychological characteristics of PSIM Yogyakarta players in wading the League 2 competition. Data collected from 27 players who are members of the PSIM Team in 2019 can be concluded that PSIM players totaling 27 people have characteristics for the aspect of motivation with a mean (38.6 ) with a percentage (97%), included in the category (very high). As for the aspect of confidence, PSIM players have an average (30) with a percentage (83%) in the (very high) category. For anxiety control aspect, it has average (27.6) with percentage (79%) and categorized (High), mental preparation aspect has average (18) with percentage (60%) and categorized (Medium), aspect of team attention has average (14) with a percentage (71%) and included in the category (High), and the Concentration aspect had an average (23.8) with a percentage (76%) and included in the category (very High). Keywords: characteristic, PSIM player Introduction The success of PSSI in the holding of the National football named Liga 1, Liga 2 and Liga 3 (Liga Nusantara) generates new hope for Indonesian football, although it cannot be separated from some unfavorable records of referee leadership, supporters riots and fights between players, but PSSI continues to look forward with various programs that continue to be rolled out for the advancement of football in the country of Indonesia. -

Serangan Hibrida Ancam Keamanan Nasional

HARGA KORAN ECERAN : Rp.5.000.- LANGGANAN : Rp.55.000,- (Jabodetabek) LUAR JABODETABek : Rp. 7.500,- Kamis, 24 Juni 2021 INFO NASionAL INFO OTonoMI INFO LEGISLATIF SIAPA KITA AKAN CORONA SANGKA SEGERA MENYERANG KING MAKER BANGKIT PARLEMEN 3 4 6 4ABAIKAN NASIHAT PARA AHLI JOKOWI LEBIH SAYanG EkONOMI JAKARTA - Seruan dari para ahli ke- kalangan ahli kesehatan dan komunitas,” tutur Jokowi epidemiologi mengusulkan dari Istana Bogor, Jawa sehatan agar pemerintah kembali kebijakan PSBB, yang populer Barat, kemarin. mem berlakukan Pembatasan Sosial dijuluki lockdown. Menurut Jokowi, Presiden menyambut baik pemerintah melihat Berskala Besar (PSBB), tidak meng- usulan itu. Tapi, keputusanya kebijakan PPKM ubah pendirian Presiden Jokowi. tidak berubah. Menurut Joko- mikro masih Pem berlakuan Pembatasan Kegiatan wi, pemerintah telah mempela- menjadi yang jari berbagai opsi penanganan kebijakan Masyarakat atau PPKM skala Mikro COVID-19 dengan memper- yang pa- masih dianggap paling tepat. hitungkan kondisi ekonomi, ling tepat sosial, politik di Indonesia dan untuk Di tengah lonjakan kasus Jumlah warga Indonesia juga pengalaman dari negara k o n t e k s baru COVID-19, pemerintah yang terpapar COVID-19 se- lain. saat ini memperketat PPKM Mikro jak Maret 2020 telah tembus ”Pemerintah telah memu- karena sejak 22 Juni hingga 5 Juli 2.033.421 orang. tuskan PPKM Mikro masih bisa berjalan 2020. Sementara itu, seperti Ketika varian baru yang lebih menjadi kebijakan yang paling tanpa mematikan diprediksi para ahli, lonjakan menular ditemukan di bebera- tepat untuk menghentikan laju ekonomi rakyat. Ya, pemulihan kasus baru semakin tak terk- pa wilayah Jawa dan tingkat penularan COVID-19 hingga ekonomi tetap jadi prioritas. endali. -

I KEWARGAAN BUDAYA SUPORTER PERSIS SOLO

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI KEWARGAAN BUDAYA SUPORTER PERSIS SOLO Tesis Untuk Memenuhi Persyaratan Mendapat Gelar Magister Humaniora (M. Hum.) di Program Magister Ilmu Religi dan Budaya Universitas Sanata Dharma Yogyakarta Oleh: Claudius Hans Christian Salvatore 136322008 Program Magister Ilmu Religi dan Budaya Universitas Sanata Dharma Yogyakarta 2018 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI vi KATA PENGANTAR Berawal dari kesukaan penulis dalam dunia sepak bola dan mengamati pertandingan sepak bola baik secara langsung maupun di televisi. Muncul sebuah pertanyaan-pertanyaan yang harus penulis jawab. Dengan proses yang sangat panjang akhirnya penulis mengambil fenomena yang terjadi di suporter Persis Solo. Untuk itu penulis mengambil judul penelitian Tesis Kewargaan Suporter Persis Solo dalam penulisan Tesis ini. Jujur penulis dalam penulisan ini sangat memerlukan waktu yang sangat lama, dengan banyak kendala yang dialami penulis dari hal teori maupun dari kegalauan lainya. Akhirnya, setelah mengalami banyak kendala Tesis ini bisa penulis selesaikan. Banyak pihak yang membantu dalam menyelesaikan Tesis ini dalam hal penulisan maupun dalam hal memberikan semangat dalam penulisan ini yang hampir saja membuat penulis putus asa dalam menyelesaikannya. Oleh sebab itu penulis mengucapkan terima kasih kepada 1. Romo Banar sebagai pembimbing yang sabar dalam membimbing, ngancani sampai akhir dari penulisan Tesis ini. Mohon maaf belum bisa kasih yang terbaik dalam penulisan tesis ini. tak lupa kami ucapkan terima kasih kepada Dosen-dosen IRB lainya. Mbak Devy yang setia ngancani dalam kuliah penulisan tesis, Mbak Katrin, Pak Praktik, Pak Nardi, Pak Tri, Romo Bas, Romo Budi dan Romo Bagus. -

Berawal Dari Kecintaan, Berproses Dalam Media Komunitas Sepakbola

BERAWAL DARI KECINTAAN, BERPROSES DALAM MEDIA KOMUNITAS SEPAKBOLA : MENENGOK MANAJEMEN MEDIA KOMUNITAS BERBASIS FANS SEPAKBOLA Fajar Junaedi, Budi Dwi Arifianto Program Studi Ilmu Komunikasi Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta � [email protected] Pendahuluan Sepakbola dan suporter adalah bagian yang tidak bisa dipisahkan. Sepakbola telah mengubah pikiran normal manusia menjadi tergila- gila, kecintaan mereka terhadap klub yang dibelanya telah menjadikan bukti kesetiaan mereka terhadap klub. Di sudut - sudut jalan dipasang berbagai hiasan bendera maupun spanduk dengan berbagai warna kebesarannya telah menjadi simbol dan identitas mereka (Santosa, 2014 : 5). Fenomena ini dengan mudah dijumpai di Yogyakarta (terutama Kota Yogyakarta dan Kabupaten Sleman), Magelang dan Surakarta – yang lazim juga disebut Kota Solo – dan Surabaya. Di Yogyakarta, klub PSIM Yogyakarta berkandang, di Sleman klub PSS Sleman berkandang, di Kota Magelang klub PPSM Magelang berkandang, di Surakarta klub Persis Solo menjadi simbol kebesaran kota dan di Surabaya, klub Persebaya menjadi simbol kebanggaan kota. Klub – klub ini, pada tahun 2017, berada di Liga 2, sebuah jenjang kompetisi sepakbola kelas dua yang berada di bawah Liga 1. Meskipun berada di kasta kedua kompetisi sepakbola profesional Indonesia, klub – klub ini tetap mendapat dukungan semangat dari para fans yang secara sukarela menjadi suporternya. Suporter adalah pemain keduabelas yang dibilang paling fanatik dan antusias dalam membela klub yang dicintainya. Susah maupun senang, hati mereka melebur menjadi satu saat tim mereka berjuang meraih kemenangan. Inilah sepakbola yang telah membuka mata mereka bak separti pahlawan yang sedang berjuang dengan mengusung 217 Kolase Komunikasi di Indonesia gengsi dan harga diri mereka dipertaruhkan di stadion hanya untuk menyandang gelar sang pemenang (Santosa, 2014 : 5). Fans sepakbola adalah konsumen yang sudah tersedia bagi media massa untuk mendapatkan audiens, maka olahraga menjadi salah satu isu seksi di media. -

Perancangan Interior Kompleks Wisma Psim Yogyakarta

NASKAH PUBLIKASI KARYA DESAIN PERANCANGAN INTERIOR KOMPLEKS WISMA PSIM YOGYAKARTA IVO SATYA WICAKSONO NIM: 1210007123 PROGRAM STUDI DESAIN INTERIOR FAKULTAS SENI RUPA INSTITUT SENI INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2018 NASKAH PUBLIKASI KARYA DESAIN PERANCANGAN INTERIOR KOMPLEKS WISMA PSIM YOGYAKARTA IVO SATYA WICAKSONO 1 Program Studi Desain Interior, Jurusan Desain, Fakultas Seni Rupa, ISI Yogyakarta Jl. Parangtritis km 6,5 Sewon Bantul Yogyakarta 1) Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Wisma Athletes and PSIM Soccer Training Center in Yogyakarta is a plan or process to restore the quality of football matches in D.I. Yogyakarta especially in Yogyakarta City. This plan was motivated by the problem of decreasing the quality of the PSIM football club due to the lack of maturity of PSIM players when playing soccer. The lack of facilities in old buildings is a factor that makes PSIM athlete's game quality less good. The athlete's house and tranining center are trying to bring a healthy, environmentally friendly and energy-efficient building atmosphere. So that it is expected that later in the final design concept produced can improve the quality of health, fitness, and skills in playing footbal. Keywords : Athletes Guesthouse, Healthy, Environmentally Friendly, Save Energy ABSTRAK Wisma Atlet dan Training Center Sepak Bola PSIM di Yogyakarta merupakan rencana atau proses untuk mengembalikan lagi kualitas persepak bolaan di D.I.Yogyakarta khususnya pada Kota Yogyakarta. Rencana ini dilatar belakangi oleh permasalahan menurunnya kualitas klub sepak bola PSIM yang dikarenakan kurang matangnya pemain PSIM ketika bermain sepak bola. Minimnya fasilitas yang ada pada bangunan lama menjadi faktor yang buat kualitas permainan atlet PSIM menjadi kurang baik. -

Bab Iv Hasil Penelitian Evaluasi Dan Pembahasan A

BAB IV HASIL PENELITIAN EVALUASI DAN PEMBAHASAN A. Deskripsi Hasil Penelitian 1. Gambaran Umum PSIM Yogyakarta Perserikatan Sepakbola Indonesia Mataram, atau yang lebih dikenal dengan PSIM Yogykarta, adalah salah satu klub tertua di Indonesia dan juga salah satu klub yang mempelopori berdirinya PSSI. Sejarah berdirinya PSIM Yogyakarta terjadi pada tanggal 5 September 1929 dengan nama organisasi sepakbola Perserikatan Sepak Raga Mataram atau disingkat (PSM). Baru pada tanggal 27 Juli 1930 PSM diubah menjadi Perserikatan Sepak Bola Indonesia Mataram (PSIM) sebagai upaya dan tuntutan pergerakan kebangsaan untuk mencapai kemerdekaan Indonesia. Sebagai salah satu klub yang memepelopori terbentuknya federasi sepakbola nasional yang sekarang dikenal dengan nama PSSI, PSIM sudah pernah merasakan gelar juara kompetisi PSSI di tahun 1932. Sedangkan ketika berkompetisi di era Perserikatan, klub yang memiliki julukan ‘Laskar Mataram’ belum pernah menjuarai memperoleh gelar juara. Pada era Liga Indonesia, prestasi terbaik PSIM menjadi runner-up Divisi I musim 1996/1997, dan juara 1 Divisi I di tahun 2005. Kemudian ketika pembentukan Liga Super Indonesia (Liga 1) pada tahun 2008 menggantikan Divisi Utama sebagai kasta tertinggi liga Indonesia, ternyata perubahan tersebut 99 mengakibatkan PSIM Yogyakarta tidak dapat ambil bagian karena PSSI hanya menyeleksi 9 klub teratas di masing-masing wilayah Divisi Utama Liga Indonesia 2007. Hingga memasuki musim kompetisi Liga 2 Indonesia 2019, PSIM masih belum mampu promosi atau berkompetisi di Liga 1 Indonesia. 2. Evaluasi Konteks a. Visi dan Misi Klub Sebagai suatu klub sepakbola profesional yang juga didukung dengan sistem keorganiasian, sudah selayaknya mempunyai visi dan misi dalam menjalani kompetisi liga sepakbola. Selama berkompetisi di Liga 2 Indonesia, PSIM mempunyai visi untuk mendukung pemain-pemain asli dari daerah Jogja mampu menjadi pemain yang mampu berkompetisi di liga profesional Indonesia, terutama liga 1 dan dapat menjadi andalan Tim Nasional Indonesia. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. LATAR BELAKANG Dalam Dunia

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. LATAR BELAKANG Dalam dunia sepakbola yang semakin kompetitif ini, tantangan yang dihadapi oleh klub yang berkompetisi di Liga Indonesia sangatlah berat. Tantangan yang dihadapi tidak hanya berasal dari dalam klub seperti tantangan sumber daya manusia, terbatasnya modal dan menurunnya produktivitas tetapi juga tantangan yang berasal dari luar klub. Tantangan yang berasal dari luar klub misalnya, semakin tingginya tuntutan dari Stakeholder, tekanan dari suporter serta perkembangan teknologi yang semakin canggih. Dengan adanya tantangan tersebut, klub dituntut untuk lebih profesional dalam mengelola bisnisnya dan terus berupaya untuk merumuskan serta menyempurnakan strategi-strategi bisnis mereka dalam usaha memenangkan persaingan. Untuk bisa bersaing tentu dibutuhkan dukungan finansial yang kuat seperti menggaet sponsor. Sponsorship adalah bentuk bantuan dana atau bisa juga produk atau layanan sebagai ganti promosi. Dengan adanya sponsor maka keuangan klub akan terbantu dalam mengarungi kompetisi. Apalagi setelah dilarangnya penggunaan Anggaran Pendapatan dan Belanja Daerah (APBD) untuk membiayai sepakbola tentu hal ini membuat klub harus memutar otak untuk mencari sponsor guna bertahan di kancah sepakbola indonesia. Hal ini dilakukan oleh salah satu klub PSIM Yogyakarta beberapa tahun terakhir, untuk mengarungi kompetisi Liga 1 Indonesia PSIM Yogyakarta menggaet beberapa sponsor untuk mencari dana selain dari pemasukan tiket di setiap pertandingannya. PSIM Yogyakarta adalah sebuah klub sepakbola di Yogyakarta yang didirikan 5 September 1929 dengan nama awal Persatuan Sepakraga Mataram (PSM). Nama Mataram digunakan karena Yogyakarta merupakan pusat kerajaan mataram. Kemudian 27 Juli 1930 diubah menjadi PSIM Yogyakarta. Pada tanggal 19 April 1930, PSIM Jogja bersama Persebaya Surabaya, Persis Solo, PPSM Magelang, Persija Jakarta dan PSM Madiun turut membidani kelahiran PSSI di Yogyakarta. -

Lampiran Berita-Berita Mengenai Kongres Luar Biasa (KLB) PSSI Di Media Indosport.Com Selama Periode November 2019

Lampiran Berita-berita mengenai Kongres Luar Biasa (KLB) PSSI di Media Indosport.com selama periode November 2019. 1 November 2019: 1. Disebut Ingin Menangkan Iwan Bule di Kongres PSSI, Begini Tanggapan PSMS Medan ( https://www.indosport.com/sepakbola/20191101/disebut-ingin-menangkan-iwan- bule-di-kongres-pssi-ini-tanggapan-psms ) INDOSPORT.COM - Kubu PSMS Medan memberikan jawaban terkait tudingan mereka yang sepakat ingin memenangkan Iwan Bule di Kongres PSSI. Pihak PSMS Medan membantah soal adanya dugaan upaya memenangkan Komjen Pol. Mochamad Iriawan atau yang akrab disapa Iwan Bule sebagai Ketua Umum PSSI. Isu ini mencuat saat Vijaya Fitriyasa, salah satu calon ketua umum PSSI, menyampaikan dalam sebuah acara talk show di televisi nasional baru-baru ini. CEO Persis Solo itu menduga Iwan memanfaatkan Satgas Antimafia Bola untuk memenangi dirinya. Dan, dia menyebut adanya dugaan upaya orang lama PSSI yang ingin memenangkan Iwan Bule. PSMS sendiri memang erat dikaitkan dengan Iwan Bule. Itu terlihat dari foto beberapa pengurus PSMS bersama Iwan Bule yang beredar beberapa waktu lalu. Hal ini menimbulkan anggapan upaya memenangkan Iwan Bule untuk di Kongres Luar Biasa PSSI 2 November mendatang. Manajemen PSMS pun segera memberikan tanggapannya. "Tentu PSMS sudah punya calon (untuk dipilih saat kongres). Tapi tidak benar dan suatu kebohongan yang besar jika disebut memenangkan Pak Iwan Bule," ungkap Sekretaris klub PSMS, Julius Raja, Kamis (31/10/19). Diakui Julius, PSMS datang dalam deklarasi Asprov PSSI se-Sumatera di Jakarta beberapa waktu lalu. "Iya kita datang saat Deklarasi Sumatera mendukung beliau. Foto yang beredar ya saat itu. Ya artinya, waktu dia (Iwan Bule) menyampaikan visi misi kita mendukung. -

Framing Pemberitaan Jawa Pos Tentang Match Fixing Dalam Sepakbola Indonesia

FRAMING PEMBERITAAN JAWA POS TENTANG MATCH FIXING DALAM SEPAKBOLA INDONESIA Disusun sebagai salah satu syarat memperoleh Gelar Strata I pada Jurusan Ilmu Komunikasi Fakultas Komunikasi dan Informatika Oleh: Danis Yhuda Kadarmanto L100140033 PROGRAM STUDI ILMU KOMUNIKASI FAKULTAS KOMUNIKASI DAN INFORMATIKA UNVERSITAS MUHAMMADIYAH SURAKARTA 2021 i ii iii FRAMING PEMBERITAAN JAWA POS TENTANG MATCH FIXING DALAM SEPAKBOLA INDONESIA Abstrak Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mengetahui bagaimana framing pemberitaan Jawa Pos tentang Match Fixing dalam Sepakbola Indonesia. Jenis penelitian yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini adalah deskriptif kualitatif. Data primer pada penelitian ini adalah berita match fixing di harian Jawa Pos priode 1-31 Desember 2018. Teknik pengumpulan data pada penelitian ini dengan menggunakan teknik observasi. Adapun analisis data pada penelitian ini menggunakan analisis framing menurut Entman. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa Jawa Pos melalui pemberitaannya, menonjolkan bahwa Match fixing dan match setting yang terjadi dalam dunia sepakbola di Indonesia merupakan hal yang harus segera diperbaiki, hal ini dikarenakan kasus tersebut bukan hanya terjadi kali ini namun telah terjadi sejak era tahun 1990-an. Selain itu, melalui pemberitaannya Jawa Pos juga menyatakan bahwa dalam kasus tersebut organisasi induk sepakbola Indonesia yaitu PSSI dianggap terkesan lelet tidak serius dalam mengusut kasus dugaan pengaturan skor yang terjadi. Kata Kunci: framing, surat kabar, match fixing Abstract This study aims to determine how the coverage of Jawa Pos news about Match Fixing in Indonesian Football. This type of research used in this research is descriptive qualitative. Primary data in this study is match fixing news in the Jawa Pos daily for the period 1-31 December 2018. The data collection techniques in this study use observation techniques.