12-13.Pdf (302.6Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adelaidean December 2001 Vol 10 No 11

Adelaidean Volume 10 Number 11 News from Adelaide University December 2001 INSIDE A sound solution The Lord of Spineless for carp the Rings invaders page 5 page 7 page 9 Securing the future: Lights, campus, action! major initiatives announced for 2002 Vice-Chancellor tackles budget issues THE Vice-Chancellor, Professor Cliff University achieves a balanced budget in 2002 Blake, has announced a series of and significant surpluses in subsequent years. initiatives aimed at strengthening This will enable us to rebuild our cash reserves Adelaide University's position as one of and look to the future with confidence." Australia's foremost research and The budget strategy aims to boost revenue by education institutions. attracting more fee-paying international The initiatives include: a comprehensive students and reduce costs through tighter budget strategy to restore the University's internal controls, an early voluntary capital base and secure its financial future; a retirement scheme, and amalgamation of stronger marketing effort to build on an some small schools/departments. increase of nearly 30% in total student "Adelaide University is recognised nationally applications for 2002 [see story page 3]; a and internationally as one of Australia's great staff renewal strategy, incorporating a universities," Professor Blake said. recruitment drive and voluntary early retirement scheme to reinvigorate the "The initiatives announced ensure that the academic staff profile; a new Graduate University will be better able to meet the School for postgraduate research students challenges of the 21st century and continue [see story page 3]; new budget control to make a significant contribution to South measures; a $20 million capital works Australia and the nation." program [see story page 4]; a new University A total of 47 Adelaide University staff had Two scenes in the latest film to star Robert Carlyle (Hamish Macbeth, The Full Monty) have Planning Office with responsibility for been accepted for early retirement under the been shot at key locations at Adelaide University. -

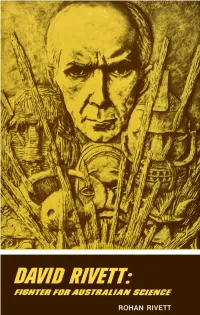

David Rivett

DAVID RIVETT: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE OTHER WORKS OF ROHAN RIVETT Behind Bamboo. 1946 Three Cricket Booklets. 1948-52 The Community and the Migrant. 1957 Australian Citizen: Herbert Brookes 1867-1963. 1966 Australia (The Oxford Modern World Series). 1968 Writing About Australia. 1970 This page intentionally left blank David Rivett as painted by Max Meldrum. This portrait hangs at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's headquarters in Canberra. ROHAN RIVETT David Rivett: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE RIVETT First published 1972 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission © Rohan Rivett, 1972 Printed in Australia at The Dominion Press, North Blackburn, Victoria Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a book Contents Foreword Vll Acknowledgments Xl The Attack 1 Carving the Path 15 Australian at Edwardian Oxford 28 1912 to 1925 54 Launching C.S.I.R. for Australia 81 Interludes Without Playtime 120 The Thirties 126 Through the War-And Afterwards 172 Index 219 v This page intentionally left blank Foreword By Baron Casey of Berwick and of the City of Westminster K.G., P.C., G.C.M.G., C.H., D.S.a., M.C., M.A., F.A.A. The framework and content of David Rivett's life, unusual though it was, can be briefly stated as it was dominated by some simple and most unusual principles. He and I met frequently in the early 1930's and discussed what we were both aiming to do in our respective fields. He was a man of the most rigid integrity and way of life. -

Larrikins, Rebels and Journalistic Freedom in Australia

Larrikins, Rebels and Journalistic Freedom in Australia Josie Vine Larrikins, Rebels and Journalistic Freedom in Australia Josie Vine Larrikins, Rebels and Journalistic Freedom in Australia Josie Vine RMIT University Melbourne, VIC, Australia ISBN 978-3-030-61855-1 ISBN 978-3-030-61856-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61856-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affliations. -

Networked Knowledge Media Briefing Rupert Max Stuart Homepage This

Networked Knowledge Media Briefing Rupert Max Stuart Homepage This page setup by Dr Robert N Moles Black And White Review / Margaret Pomeranz and David Stratton Comments by Margaret Pomeranz In 1959 an aboriginal man Max Stuart was arrested for the rape and murder of a young girl on the beach at Ceduna South Australia. His trial and subsequent appeals became a cause celebre... it was never a case of black and white... When lawyer David O'Sullivan (Robert Carlyle) is assigned to defend Max Stuart (David Ngoombujarra), he has no idea that his involvement will lead him on a collision course with the police and with the justice system. He learns that Max's confession has been beaten out of him, that his confession is one he could not possibly have made, this with the help of Father Tom Dixon (Colin Friels). But the entrenched racism of the times makes Max's conviction a foregone conclusion, particularly with that bastion of the establishment, Crown Solicitor Roderic Chamberlain (Charles Dance) leading the case for the prosecution. O'Sullivan's refusal to accept the verdict, his desperate search for a basis for appeal will not only involve his law partner Helen Devaney (Kerry Fox) and the young Rupert Murdoch (Ben Mendelsohn) and Rohan Rivett (John Gregg), the editor of the Adelaide Advertiser, but will take him on a journey to the highest court in the system – the Privy Council in England. Black and White explores this fascinating and seminal piece of Australian history in a rather old-fashioned way. Dialogue is delivered in a declamatory style that just seems clunky, giving scenes a distinct lack of credibility. -

Dislocating the Frontier Essaying the Mystique of the Outback

Dislocating the frontier Essaying the mystique of the outback Dislocating the frontier Essaying the mystique of the outback Edited by Deborah Bird Rose and Richard Davis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Dislocating the frontier : essaying the mystique of the outback. Includes index ISBN 1 920942 36 X ISBN 1 920942 37 8 (online) 1. Frontier and pioneer life - Australia. 2. Australia - Historiography. 3. Australia - History - Philosophy. I. Rose, Deborah Bird. II. Davis, Richard, 1965- . 994.0072 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Indexed by Barry Howarth. Cover design by Brendon McKinley with a photograph by Jeff Carter, ‘Dismounted, Saxby Roundup’, http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn3108448, National Library of Australia. Reproduced by kind permission of the photographer. This edition © 2005 ANU E Press Table of Contents I. Preface, Introduction and Historical Overview ......................................... 1 Preface: Deborah Bird Rose and Richard Davis .................................... iii 1. Introduction: transforming the frontier in contemporary Australia: Richard Davis .................................................................................... 7 2. -

Adelaidean December 2002

Adelaidean Volume 11 Number 11 News from the University of Adelaide December 2002 INSIDE Andy Thomas New urban Theatre Guild drops in environment centre turns 65 page 6 page 7 page 10 Control your power costs How research is impacting on the future of your power supply THE BUZZING sound from the black Mr Vowles said people do not see these price box on the television could not have come signals so they keep their air conditioning on at a worse time. It’s 3:00 on a sweltering during the highest temperatures of the day. Sunday afternoon. The family is relaxing Both researchers caution that change is in the lounge enjoying the cool air coming and with it, lifestyles will be altered. generated by the welcome air conditioner. Adapting to such changes in the supply of This temporary utopia is about to be electricity is a feature of the group’s research. disrupted: the household has a decision to They are currently working with seven make and the quicker they respond, the Australian power companies to improve the quicker they’ll be able to continue with their operation and reliability of the power supply lives. But it won’t be the same. that could potentially save the industry The buzzing sound is to advise them of millions of dollars. an electricity price increase and the family has The project hinges around its title: “to to decide to keep the air conditioning on and enhance the dynamic performance of large absorb the additional cost, or suffer in silence. power systems by means of automatic “Welcome to the world stabilising controllers”. -

David Rivett: FIGHTER for AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE

DAVID RIVETT: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE OTHER WORKS OF ROHAN RIVETT Behind Bamboo. 1946 Three Cricket Booklets. 1948-52 The Community and the Migrant. 1957 Australian Citizen: Herbert Brookes 1867-1963. 1966 Australia (The Oxford Modern World Series). 1968 Writing About Australia. 1970 This page intentionally left blank David Rivett as painted by Max Meldrum. This portrait hangs at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's headquarters in Canberra. ROHAN RIVETT David Rivett: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE RIVETT First published 1972 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission © Rohan Rivett, 1972 Printed in Australia at The Dominion Press, North Blackburn, Victoria Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a book Contents Foreword Vll Acknowledgments Xl The Attack 1 Carving the Path 15 Australian at Edwardian Oxford 28 1912 to 1925 54 Launching C.S.I.R. for Australia 81 Interludes Without Playtime 120 The Thirties 126 Through the War-And Afterwards 172 Index 219 v This page intentionally left blank Foreword By Baron Casey of Berwick and of the City of Westminster K.G., P.C., G.C.M.G., C.H., D.S.a., M.C., M.A., F.A.A. The framework and content of David Rivett's life, unusual though it was, can be briefly stated as it was dominated by some simple and most unusual principles. He and I met frequently in the early 1930's and discussed what we were both aiming to do in our respective fields. He was a man of the most rigid integrity and way of life. -

Imagereal Capture

ARTICLES The Hon Justice Michoel Kirby AC CMG* BLACK AND WHITE LESSONS FOR THE AUSTRALIAN JUDICIARY ABSTRACT Using the 'celluloid metaphor' of the new Australian film Black and White, the author describes the features of the case of Rupert Max Stuart that reached the High Court in 1959. He outlines the imperfections of the legal process and acknowledges that the prisoner's life was ultimately saved not by the legal system or the judicial process but by a dedicated group of journalists and other citizens who shared the High Court's expressed 'anxiety' about the case but were more determined to give effect to that 'anxiety'. The author describes improvements in the criminal justice system since 1959. These include legal protections for indigenous people; the requirements of legal representation as expressed in Dietrich; the rigorous rule for confessions to police adopted in McKinnej.; the stricter rules governing criminal appeals: the larger insistence on prosecutorial impartiality; the enforcement of requirements for competence of lawyers; and the advent of DNA and other scientific * Justice of the High Court of Australia. This article is based on a lecture given at the Law School, The University of Adelaide, 12 August 2002. 196 KIRBY - BLACK AND WHITE LESSONS FOR THE JUDICIARY evidence to reduce the risks of miscarriages of justice. The author suggests that the Stuart affair illustrates how cleverness is not enough in the law. There must also be a commitment to justice. t seems that everyone who lived in South Australia in the late 1950s and 1960s was touched by the Stuart affair.' Most have a story to tell. -

German Ethnography in Australia

10 ‘Only the best is good enough for eternity’: Revisiting the ethnography of T. G. H. Strehlow Jason Gibson1 In September 2006, I sat with one of the few men still alive who had performed, in 1965, for the films of Theodor George Henry (T. G. H.) Strehlow (1908–78). We watched an hour-long silent colour film that depicted more than 27 different Anmatyerr ceremonies and included the participation of up to 10 individuals. The film had never been publicly screened before and had certainly never been viewed by Aboriginal people in the four decades since its making. I became fascinated with the manner in which films like this had been made and curious as to the intellectual style, theoretical agenda and methodological processes that drove this ethnographic project. Though plentiful analyses of Strehlow’s moral character and his intriguing life abound (Hill 2002; Morton 1993; McNally 1981), there have been very few attempts to interrogate the theoretical influences and motivations that shaped his ethnographic practice. One exception is Philip Jones’s 1 Harold Payne Mpetyan, Ken Tilmouth Penangk, Max Stuart Kngwarraye (deceased), Paddy Willis Kemarr, Archie Mpetyan, Ronnie Penangke McNamara, Malcolm Heffernan Pengart and Huckitta Lynch Penangk were particularly generous in their memories of ‘Strehlow-time’. I am grateful to the Monash Indigenous Centre and the Strehlow Research Centre for making the fieldwork and archival research for this chapter possible. 243 GERMAN ETHNOGRAPHY IN AUSTRALIA (2004) discussion of the young Strehlow’s ‘mentors’, although this analysis is deliberately contained to the earliest stages of his career. Others have touched on his theoretical framework (Rowse 1992) and some of his contributions to Australian anthropology (Morton 1997; Austin- Broos 1997; Dousset 1999; Kenny 2004), but in-depth examinations of Strehlow’s methods and achievements as an ethnographer are not particularly well developed. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

The offices of the Bunyip, Gawler, South Australia, on 29 January 2003 when the ANHG editor visited to interview editor John Barnet and brother Craig. The Barnets, who had owned the paper since helping to found it in 1863, sold the paper on 31 March 2003 to the Taylor family, of the Murray Pioneer, Renmark. The Bunyip celebrated its 150th anniversary on 5 September this year. It began as a monthly satirical journal under the title of the Bunyip; or Gawler Humbug Society’s Chronicle, Flam! Bam!! Sham!!! It omitted the Humbug Society guff from its title in 1864, appeared twice a month in 1865 and weekly from 1866. William Barnet, the founding printer and owner, died in 1895. The Barnets’ possible sale of the Bunyip had been discussed since soon after the death of third-generation owner Kenneth Lindley Barnet on 16 May 2000. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 74 October 2013 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, PO Box 8294 Mount Pleasant Qld 4740. Ph. +61-7-4942 7005. Email: [email protected]/ Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra. Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 9 December 2013. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. A composite index of issues 1 to 75 of ANHG is being prepared. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

ABOVE: The Courier-Mail’s Page 1 headline on 11 August 1945 (by courtesy of Trove). In Mackay, the Daily Mercury’s editor believed he had stolen a march on other Australian papers with news of the Pacific war’s end. Had he? See story on Harry Moore, 80.4.1, below. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 80 December 2014 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, PO Box 8294 Mount Pleasant Qld 4740. Ph. +61-7-4942 7005. Email: [email protected]/ Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra. Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 26 February 2015. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 80.1.1 Fairfax: Whish-Wilson on Corbett A former chief executive of Fairfax Media’s metropolitan division, Lloyd Whish-Wilson says it is time for the current chairman Roger Corbett to leave the company (Australian, Media section, 6 October 2014). Whish-Wilson, who spent more than 20 years in senior executive roles with Rural Press Ltd and Fairfax Media before retiring in 2011, says a lack of newspaper experience on the Fairfax board has been a major factor in the problems besieging its newspapers. He said the Sydney Morning Herald and other Fairfax papers were now riddled with errors as a result of inexperienced journalists and fewer sub-editors. -

Report of the Royal Commission in Regard to Rupert Max Stuart

[P.P. 80 SOUTH AUSTRALIA REPORT OF THE Royal Commission in regard to Rupert Max Stuart .Laid on the table of the Legislative Council 3rd December, 1959, and ordered to be printed 3rd December, 1959. [Estimated cost of printing (250), £114 9s. 5d.] BY AUTHORITY: W. L. HA WES, Government Printer, Adelaide 1959 Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2010 - www.aiatsis.gov.au [P.P. 80 REPORT OF THE ROYAL COMMISSION IN REGARD TO RUPERT MAX STUART To His Excellency Air Vice-Marshal Sir Robert Allingham George, Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, and upon whom has been conferred the decoration of the Military Cross, Governor in and over the State of South Australia and its Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR EXCELLENCY. By a Commission under Your Excellency's hand dated 30th July, 1959, we were appointed a Royal •Commission to enquire into and report to Executive Council upon:— (1) The facts purporting to be disclosed in certain statutory declarations purporting to be made by Norman George Gieseman, Edna Gieseman and Betty Hopes all of Burpengarry in the State of Queensland, relative to the movements, actions and intentions of Rupert Max Stuart now a prisoner in Her Majesty's Gaol at Adelaide. (2) The movements of the said Rupert Max Stuart during Saturday, the 20th day of December, 1958. (3) The reasons why the said statements were not made or furnished to the Supreme Court of South Australia or to an appropriate authority before the dates when they were respectively made and furnished.