Contents 1 1.1 1.2 1.3 2 2.1 2.2 3 3.1 3.2 3.2.1 3.2.2 3.2.2.1 3.2.2.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Workbook B- 1

MICHAEL BEND ABeCeDarian STUDENT WORKBOOK B- 1 FA L L 2 0 0 6 © ABECEDARIAN COMPANY JULY 2006. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. a•be•ce•dar•i•an n. (ay-bee-cee-dair-ee-an) 1. One who teaches or studies the alphabet. 2. One who is just learning; a beginner. a•be•ce•dar•i•an adj. 1. Having to do with the alphabet. 2. Being arranged alphabetically. 3. Elementary or rudimentary. [Middle English, from Medieval Latin abecedarium, alphabet, from Late Latin abecedarius, alphabetical : from the names of the letters A B C D + -arius, -ary.] from The American Heritage Dictionary, Third Edition Copyright © 2000-2006 ABeCeDarian Company Visit us at www.abcdrp.com June 12,2006 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 DATE ASSIGNMENT COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 3 DATE ASSIGNMENT 4 oa o-e o ow oe ough COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 1 Unit One 5 Unit 1 Sorting words with oa o-e o ow oe ough Read the words below and sort them using the following record sheet. Remember, always say the sound before you write it. 1. b oa t 5. g r ow 9. h o m e 2. sh ow 6. r o p e 10. g o 3. t oe 7. l oa f 11. n o t e 4. m o s t 8. c oa t 12. th ough 1 2 3 4 5 6 oa o-e o ow oe ough 6 Unit 1 I Spy with oa o-e o ow oe ough Underline oa, o-e, o, ow, oe, or ough in the words below and read them. -

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Faculty of Humanities, Department of Linguistics and Faculty of Education, Indigenous Education Art Napoleon, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental Member iii ABstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental MemBer Through a review of literature and a qualitative inquiry of Cree language practitioners and knowledge keepers, this study explores traditional concepts related to Cree worldview specifically through the lens of nîhiyawîwin, the Cree language. Avoiding standard dictionary approaches to translations, it provides inside views and perspectives to provide broader translations of key terms related to Cree values and principles, Cree philosophy, Cree cosmology, Cree spirituality, and Cree ceremonialism. It argues the importance of providing connotative, denotative, implied meanings and etymology of key terms to broaden the understanding of nîhiyaw tâpisinowin and the need -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities June / July, 2012 ClosingVOLUME 31 - NUMBER 2 The Gap The Importance of Play for Kids with Disabilities Building Independence with Picture Directions I Just Bought the New iPAD… Now what??? Physical Access and Training to Use the iPad Help for THOSE Classrooms DISKoveries 30th Annual Closing The Gap Conference Details Permit No. 166 No. Permit Hutchinson, MN 55350 MN Hutchinson, U.S POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S www.closingthegap.com AUTO PRSRT STD PRSRT STAFF Dolores Hagen ...... PUBLISHER contents june / july, 2012 Budd Hagen ..................EDITOR volume 31 | number 2 Connie Kneip .................................. VICE PRESIDENT / GENERAL MANAGER 4 The Importance of Play for Kids 14 Physical Access and Training to Megan Turek ........... MANAGING with Disabilities Use the iPad EDITOR / By Sue Redepenning and By Patricia Bahr and Katie Duff SALES MANAGER Jennifer Mundl Jan Latzke ...... SUBSCRIPTIONS Sarah Anderson .............................. ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Becky Hagen .....................SALES Marc Hagen ............................WEB DEVELOPMENT SUBSCRIPTIONS $39 per year in the United States. $55 per year to Canada and Mexico (air mail.) All subscriptions from outside 17 Help for THOSE Classrooms the United States must be accom- panied by a money order or a check By Julie Rick drawn on a U.S. bank and payable in U.S. funds. Purchase orders are accepted from schools or institutions in the United States. 8 Building Independence with PUBLICATION INFORMATION Picture Directions Closing The Gap (ISSN: 0886-1935) is By Pat Crissey published bi-monthly in February, April, June, August, October and December. Single copies are available for $7.00 (postpaid) for U.S. -

The Evolution of Health Status and Health Determinants in the Cree Region (Eeyou Istchee)

The Evolution of Health Status and Health Determinants in the Cree Region (Eeyou Istchee): Eastmain 1-A Powerhouse and Rupert Diversion Sectoral Report Volume 1: Context and Findings Series 4 Number 3: Report on the health status of the population Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay The Evolution of Health Status and Health Determinants in the Cree Region (Eeyou Istchee): Eastmain-1-A Powerhouse and Rupert Diversion Sectoral Report Volume 1 Context and Findings Jill Torrie Ellen Bobet Natalie Kishchuk Andrew Webster Series 4 Number 3: Report on the Health Status of the Population. Public Health Department of the Cree Territory of James Bay Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay. Authors Jill Torrie Cree Board of Health & Social Services of James Bay (Montreal) [email protected] Ellen Bobet Confluence Research and Writing (Gatineau) [email protected] Natalie Kishchuk Programme evaluation and applied social research consultant (Montreal) [email protected] Andrew Webster Analyst in health negotiations, litigation, and administration (Ottawa) [email protected] Series editor & co-ordinator: Jill Torrie, Cree Public Health Department Cover design: Katya Petrov [email protected] Photo credit: Catherine Godin This document can be found online at: www.Creepublichealth.org Reproduction is authorised for non-commercial purposes with acknowledgement of the source. Document deposited on Santécom (http://www. Santecom.qc.ca) Call Number: INSPQ-2005-18-2005-001 Legal deposit – 2nd trimester 2005 Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec National Library of Canada ISSN: 2-550-443779-9 © April 2005. -

Strand 1: Foundational Language Skills

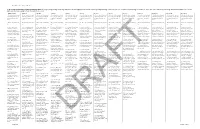

English Language Arts and Reading (1) Developing and Sustaining Foundational Language Skills: Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing. Students develop oral language and word structure knowledge through phonological awareness, print concepts, phonics and, morphology to communicate, decode and encode. Students apply knowledge and relationships found in the structures, origins, and contextual meanings of words. The student is expected to: Kindergarten Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 English I English II English III English IV (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; (B) develop -

Sounds to Graphemes Guide

David Newman – Speech-Language Pathologist Sounds to Graphemes Guide David Newman S p e e c h - Language Pathologist David Newman – Speech-Language Pathologist A Friendly Reminder © David Newmonic Language Resources 2015 - 2018 This program and all its contents are intellectual property. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or reproduced in any way, including but not limited to digital copying and printing without the prior agreement and written permission of the author. However, I do give permission for class teachers or speech-language pathologists to print and copy individual worksheets for student use. Table of Contents Sounds to Graphemes Guide - Introduction ............................................................... 1 Sounds to Grapheme Guide - Meanings ..................................................................... 2 Pre-Test Assessment .................................................................................................. 6 Reading Miscue Analysis Symbols .............................................................................. 8 Intervention Ideas ................................................................................................... 10 Reading Intervention Example ................................................................................. 12 44 Phonemes Charts ................................................................................................ 18 Consonant Sound Charts and Sound Stimulation .................................................... -

Refusing to Hyphenate: Doukhobor Autobiographical Discourse

REFUSING TO HYPHENATE: DOUKHOBOR AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL DISCOURSE By JULIE RAK, M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School ofGraduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Doctorate McMaster University © Copyright by Julie Rak, June 1998 DOCTORATE (1998) (English) McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Refusing to Hyphenate: Doukhobor Autobiographical Discourse AUTHOR: Julie Rak, B.A. (McMaster University), M.A. (Carleton University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Lorraine M. York NUMBER OF PAGES: vi,256 (ii) Abstract My thesis, Refusing to Hyphenate: Doukhobor Autobiographical Discourse brings together recent theories ofautobiography with a consideration ofalternative autobiographical writing and speaking made by a Russian-speaking migrant group, the Doukhobors ofCanada. The situation ofthe Doukhobors is ideal for a consideration of alternate autobiographical forms, since Doukhobors have fallen outside liberal democratic discourses ofCanadian nationalism, land use and religion ever since their arrival in Canada in 1899. They have turned to alternate strategies to retell their own histories against the grain ofthe sensationalist image ofDoukhobors propagated by government commissions and by the Canadian media. My study is the first to recover archived autobiographical material by Doukhobors for analysis. It also breaks new ground by linking new developments in autobiography theory with other developments in diaspora theory, orality and literacy and theories ofperformativity, as well as criticism that takes issues about identity and its relationship to power into account. When they had to partially assimilate by the 1950s, some Doukhobors made autobiographical writings, translations and recordings that included interviews, older autobiographical accounts and oral histories about their identity as a migratory, persecuted people who resist State control. Others recorded their protests against the British Columbian government from the 1930s to the 1960s in collective prison diaries and legal documents. -

Parietal Dysgraphia: Characterization of Abnormal Writing Stroke Sequences, Character Formation and Character Recall

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 99–114 99 IOS Press Parietal dysgraphia: Characterization of abnormal writing stroke sequences, character formation and character recall Yasuhisa Sakuraia,b,∗, Yoshinobu Onumaa, Gaku Nakazawaa, Yoshikazu Ugawab, Toshimitsu Momosec, Shoji Tsujib and Toru Mannena aDepartment of Neurology, Mitsui Memorial Hospital, Tokyo, Japan bDepartment of Neurology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan cDepartment of Radiology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Abstract. Objective: To characterize various dysgraphic symptoms in parietal agraphia. Method: We examined the writing impairments of four dysgraphia patients from parietal lobe lesions using a special writing test with 100 character kanji (Japanese morphograms) and their kana (Japanese phonetic writing) transcriptions, and related the test performance to a lesion site. Results: Patients 1 and 2 had postcentral gyrus lesions and showed character distortion and tactile agnosia, with patient 1 also having limb apraxia. Patients 3 and 4 had superior parietal lobule lesions and features characteristic of apraxic agraphia (grapheme deformity and a writing stroke sequence disorder) and character imagery deficits (impaired character recall). Agraphia with impaired character recall and abnormal grapheme formation were more pronounced in patient 4, in whom the lesion extended to the inferior parietal, superior occipital and precuneus gyri. Conclusion: The present findings and a review of the literature suggest that: (i) a postcentral gyrus lesion can yield graphemic distortion (somesthetic dysgraphia), (ii) abnormal grapheme formation and impaired character recall are associated with lesions surrounding the intraparietal sulcus, the symptom being more severe with the involvement of the inferior parietal, superior occipital and precuneus gyri, (iii) disordered writing stroke sequences are caused by a damaged anterior intraparietal area. -

Symbols of Communication: the Case of Àdìǹkrá and Other Symbols of Akan

The International Journal - Language Society and Culture URL: www.educ.utas.edu.au/users/tle/JOURNAL/ ISSN 1327-774X Symbols of Communication: The Case of Àdìǹkrá and Other Symbols of Akan Charles Marfo, Kwame Opoku-Agyeman and Joseph Nsiah Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana Abstract The Akan people of Ghana have a number of coined symbols that express various forms of infor- mation based on socio-cultural knowledge. These symbols of expression are collectively called àdìǹkrá. There are related symbols of oral orientation that seem to play the same role as àdìǹkrá. In this paper, we explore the àdìǹkrá symbols and the related ones, the individual messages they en- code and their significance in the Akan society. It is explained that most of these symbols are inspired on creation and man-made objects. Some others are also proverb-based. The àdìǹkrá symbols in par- ticular constitute a medium of objective and deep-seated socio-cultural knowledge of the Akan people. We contend that, like words and actions, the symbols represent and send various distinctive messag- es that are indisputably accepted by people who know them. The use of àdìǹkrá and the related sym- bols in modern textiles, language and literature are also discussed. Keywords: Adinkra, Akan, Communication, Culture, Symbols of expression. Introduction A symbol could be defined as a creation that represents a message, a thought, proverb etc. When a set of symbols is attributed to a particular group of people belonging to a particular culture, these symbols become a window to the understanding of aspects of their culture. -

BR-7-0533 PUB DATE 19 Jun 71 GRANT OEG-2-7-070533-4237 NOTE 281P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 070 222 24 EC 050 266 AUTHOR Kafafian, Haig TITLE Study of Man-Machine Communications Systems for the Handicapped. Volume III. Final Report. INSTITUTION Cybernetics Research Inst., Inc., Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Education for the Handicapped (DREW /OE), Washington, D.C. BUREAU NO BR-7-0533 PUB DATE 19 Jun 71 GRANT OEG-2-7-070533-4237 NOTE 281p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS *Communication Skills; *Cybernetics; *Electromechanical Aids; Equipment; *Exceptional Child Research; *Handicapped Children; Language Ability; Typewriting ABSTRACT The report describes a series of studies conducted to determine the extent to which severly handicapped students who were able to comprehend language and language structure but who were not able to write or type could communicate using various man-machine systems. Included among the systems tested were specialized electric typewriting machines, a portable telephone communications system for the deaf and/or speech handicapped, and a punctiform tactile communications system for the blind. Reported upon are pilot studies in the instruction of handicapped students at field centers, the development of screening procedures to determine latent reading ability, development of assessment procedures and forms, the use of phonemes of the Armenian language for punctographic codes used by the visually handicapped, a word and picture communications system, and other variations of man-machine communication systems. Numerous photographs illustrate the equipment described. Appendixes contain field center data, experimental studies, instructional procedures and programs, and handwriting and typing samples. (See EC 030 060, EC 050 267-050 270 for related reports.) (KW) 11II1_, h 111 !! i; il .1 Q.) /:1 t v (1. -

The Gentics of Civilization: an Empirical Classification of Civilizations Based on Writing Systems

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 49 Number 49 Fall 2003 Article 3 10-1-2003 The Gentics of Civilization: An Empirical Classification of Civilizations Based on Writing Systems Bosworth, Andrew Bosworth Universidad Jose Vasconcelos, Oaxaca, Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Bosworth, Bosworth, Andrew (2003) "The Gentics of Civilization: An Empirical Classification of Civilizations Based on Writing Systems," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 49 : No. 49 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol49/iss49/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Bosworth: The Gentics of Civilization: An Empirical Classification of Civil 9 THE GENETICS OF CIVILIZATION: AN EMPIRICAL CLASSIFICATION OF CIVILIZATIONS BASED ON WRITING SYSTEMS ANDREW BOSWORTH UNIVERSIDAD JOSE VASCONCELOS OAXACA, MEXICO Part I: Cultural DNA Introduction Writing is the DNA of civilization. Writing permits for the organi- zation of large populations, professional armies, and the passing of complex information across generations. Just as DNA transmits biolog- ical memory, so does writing transmit cultural memory. DNA and writ- ing project information into the future and contain, in their physical structure, imprinted knowledge.