Cattle Rearing Systems in the North West Region of Cameroon: Historical Trends on Changing Techniques and Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

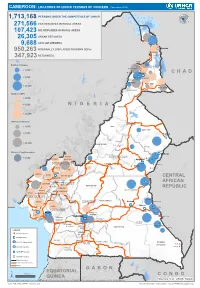

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

PASC Project Capitalization.Pdf

Table of content Acronyms ........................................................................... 2 THANKS .............................................................................. 3 Introduction ....................................................................... 5 About MBOSCUDA ........................................................ 5 About PASC .................................................................... 5 Section 1: Background and Objectives of the Project .......... 8 1.1 Background and Justification of the Project ............ 8 1.2 Objectives and Expected Results of the Project ...... 10 1.3 Target Population .................................................. 11 1.4 General Approach and Methodology ...................... 12 Section 2: Activities of the Project...................................... 15 Activity 1: Stimulate and accompany the restructuring of emerging Mbororo pastoralist CBOs ............................. 15 Activity 2: Train leaders of Mbororo pastoralist CBOs on group management ................................... 16 Activity 3. Train leaders of Mbororo pastoralist CBOs on Resource Mobilisation................................... 17 Activity 4. Train Mbororo councillors on Lobbying and Advocacy techniques ...................................... 19 Section 3: Outcomes of the Project .................................... 20 3.1 Outcomes at the level of the CBOs ......................... 20 3.2 Outcomes at the level of MBOSCUDA ................... 23 Section 4: Challenges, Lessons and Future Perspectives -

[email protected] Telephone: (237) 675184310, 697037417 Address: P.O

Website: www.camgew.com or www.camgew.org Email:[email protected]; [email protected] Telephone: (237) 675184310, 697037417 Address: P.O. Box 17 OKU-Bui Division, North West Region, Cameroon CAMGEW’s authorisation number N° 000998/RDA/JO6/ BAPP Report prepared by WIRSIY EMMANUEL BINYUY (CAMGEW Director) with support from Ngum Jai Raymond (CAMGEW Project Officer) and Sevidzem Ernestine Leikeki (CAMGEW Social Project Officer). 1 PREFACE Our world needs creative and innovative actions to make it a better place for all its occupants. The environment needs to be kept healthy for mankind to be healthy. Poverty, hunger and unemployment have stood as major challenges to mankind. The economic, environmental, political and social conditions are not making things better. We have talked about North-South partnership to make things better for the developing countries and we have also promoted south-south cooperation too but things are not changing positively as expected. Our continent- Africa has a lot of natural resources but these natural resources have not been able to help Africans get decent jobs, put food on their tables, meet other daily needs and invest in the future. There is much disparity between the rich and the poor, the able and the disable, the people in power and those being ruled, the land owners and those in need of land, etc. How do we develop an inclusive strategy that will make everyone belonging to the society? We just hope that as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been developed to replace the expired MDGs things will be getting better globally. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

CMR-3W-Cash-Transfer-Partners V3.4

CAMEROON: 3W Operational Presence - Cash Programming [as of December 2016] Organizations working for cash 10 programs in Cameroon Organizations working in Organizations by Cluster Food security 5 International NGO 5 Multi-Sector cash 5 Government 2 Economic Recovery 3 Red Cross & Red /Livelihood 2 Crescent Movement Nutrition 1 UN Agency 1 WASH 1 Number of organizations Multi-Sector Cash by departments 15 5 distinct organizations 9 organizations conducting only emergency programs 1 organizations conducting only regular programs Number of organizations by departments 15 Economic Recovery/Livelihood Food security 3 distinct organizations 5 distinct organizations Number of organizations Number of organizations by department by department 15 15 Nutrition WASH 3 distinct organizations 1 organization Number of organizations Number of organizations by department by department 15 15 Creation: December 2016 Sources: Cash Working group, UNOCHA and NGOs More information: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/cameroon/cash )HHGEDFNRFKDFDPHURRQ#XQRUJ 7KHERXQGDULHVDQGQDPHVVKRZQDQGWKHGHVLJQDWLRQVXVHGRQWKLVPDSGRQRWLPSO\RI̙FLDOHQGRUVHPHQWRUDFFHSWDQFHE\WKH8QLWHG1DWLRQV CAMEROON:CAMEROON: 3W Operational Presence - Cash Programming [as of December 2016] ADAMAOUA FAR NORTH NORTH 4 distinct organizations 9 distinct organizations 1 organization DJEREM DIAMARE FARO MINJEC CRF MINEPAT CRS IRC MAYO-BANYO LOGONE-ET-CHARI MAYO-LOUTI MINEPAT MINEPAT WFP, PLAN CICR MMBERE MAYO-REY PLAN PUI MINEPAT CENTRE MAYO-DANAY 1 organization MINEPAT LITTORAL 1 organization -

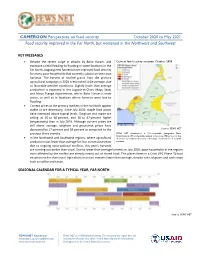

CAMEROON Perspectives on Food Security October 2020 to May 2021 Food Security Improved in the Far North, but Worsened in the Northwest and Southwest

CAMEROON Perspectives on food security October 2020 to May 2021 Food security improved in the Far North, but worsened in the Northwest and Southwest KEY MESSAGES • Despite the recent surge in attacks by Boko Haram, and Current food security situation, October 2020 excessive rainfall leading to flooding in some locations in the Far North, ongoing new harvests have improved food security for many poor households that currently subsist on their own harvests. The harvest of rainfed grains from the primary agricultural campaign in 2020 is estimated to be average, due to favorable weather conditions. Slightly lower than average production is expected in the Logone-et-Chari, Mayo Sava, and Mayo Tsanga departments, where Boko Haram is most active, as well as in locations where harvests were lost to flooding. • Current prices at the primary markets in the Far North appear stable or are decreasing. Since July 2020, staple food prices have increased above typical levels. Sorghum and maize are selling at 46 to 60 percent, and 30 to 47 percent higher (respectively) than in July 2019. Although current prices are still above average, sorghum and groundnut prices have decreased by 17 percent and 18 percent as compared to the Source: FEWS NET previous three months. FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible (Integrated Phase Classification). IPC-compatible analysis follows key IPC protocols but • In the Northwest and Southwest regions, where agricultural does not necessarily reflect the consensus of national food security production was lower than average for four consecutive years partners. due to ongoing socio-political conflicts, this year's harvests are running out earlier than usual. -

From Migrants to Nationals, from Nationals To

International Journal of Latest Engineering and Management Research (IJLEMR) ISSN: 2455-4847 www.ijlemr.com || Volume 03 - Issue 06 || June 2018 || PP. 10-19 From Nomads to Nationals, From Nationals to Undesirable Elements: The Case of the Mbororo/Fulani in North West Cameroon 1916-2008 A Historical Investigation Jabiru Muhammadou Amadou (Phd) Higher Teacher Training College Department of History The University of Yaounde 1 Abstract: The Fulani (Mbororo) are a minority group perceived as migrants and strangers by local North West groups who consider themselves their hosts and landlords. They are predominantly nomadic people located almost exclusively within the savannah zone of West and Central Africa. Their original homeland is said to be the Senegambia region. From Senegal, the Fulani continued their movement along side their cattle and headed to Northern Nigeria. Uthman Dan Fodio‟s 19th century jihad movement and epidemic outbreaks force them to move from Northern Nigeria to Northern Cameroon. From Northern Cameroon they moved down South and started penetrating the North West Region in the early 20th century. This article critically examines and considers the case of the Fulani in the North West Region of Cameroon and their recent claims to regional citizenship and minority status. The paper begins by presenting the migration, settlement and ultimate acquisition of the status of nationals by the nomadic cattle Fulani in North West Cameroon. It also analysis the difficulties encountered by this nomadic group to fully integrate themselves into the region. In the early 20th century (more precisely 1916) when they arrived the North West Region, they were warmly received by their hosts. -

Cameroon:NW/SW Highlights Needs 690K 414K 63K1 52 $9.5M

Cameroon:NW/SW WASH Update April 2020 Hand washing sensitization of community members in the North West region. Photo by NRC Highlights Needs In order to contain the spread of COVID-19, WASH partners have scaled up community 690k People in need of WASH engagement activities. More than 116,000 services in NW/SW people were reached through COVID 19 sensitization sessions in April. 414k In response to the COVID 19 pandemic, Targeted ReachOut, with support from UNICEF, 1 installed 250 communal hand washing 63k IDPs & Returnees stations in Ekondo Titi. More than 12,500 people are expected to benefit. 52 More than 10,000 individuals received WASH partners WASH and hygiene kits from WASH partners in April. $9.5m In April, about 1,600 people benefitted from required for WASH improved water supply as a result of US$9.5M installation of water distribution systems by WASH partners. Reguired WASH partners provided improved sanitation facilities to 400 people. US$0.2M Funded 1 IDP Tracking Database, May 2020 (Note: This figure is the latest displacement figure as of 16 May 2020) Website: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/cameroon/water-sanitation-hygiene For more information contact Wash Cluster Coordinator: Nchunguye Festo Vyagusa Email: [email protected] WATER Plan International, in collaboration with UNICEF completed rehabilitation of a water distribution system in Fundong, Boyo division, reaching 1,650 individuals with safe drinking water. Rehabilitation of water systems in Bamenda 2 subdivision in Mezam is ongoing. Plan International, supported by UNICEF is planning to rehabilitate two water distribution systems in Babessi sub-division of Ngo- Ketunjia division in May. -

2.3M 1.4M 679K 204K 58.1K

CAMEROON: North-West and South-West Situation Report No. 19 As of 31 May 2020 This report is produced by OCHA Cameroon in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers 1 – 31 May 2020. The next report will be issued in July 2020. MAY 2020 HIGHLIGHTS • An estimated 83,557 pupils and students are eligible to sit for end of cycle exams in 2020. • 16 out of the 37 health districts in the North-West and South-West (NWSW) have confirmed cases of COVID-19. • A cholera outbreak is reported in Tiko and Limbe health districts in the South West. • UNICEF supported the establishment of ten in-patient facilities in NWSW for the management of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) cases with complications. • UNHCR and partner have acquired land to build temporal IDP shelter in some locations in the SW. • OCHA and UNICEF supported a joint cluster led training of 81 front- line NGO staff on transmission, signs, symptoms and prevention of COVID-19 in the NW Region. Source: OCHA • IRC constructed 5 boreholes, rehabilitated 20 water distribution The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on systems and constructed 18 tank bases and tap stands, resulting in this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the an 82.4% increase in water supply coverage compared to April. United Nations. 2.3M 1.4M 679K 204K 58.1K affected people targeted for internally displaced (IDP) Returnees (former Cameroonian assistance IDP) Refugees and Asylum seekers in Nigeria Sources: Sources: Sources: Sources: Sources: Humanitarian Need Humanitarian MSNA in -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

Bambui Arts and Culture

Bambui Arts and Culture Bambui Arts and Culture By Mathias Alubafi Fubah Bambui Arts and Culture By Mathias Alubafi Fubah This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Mathias Alubafi Fubah All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0619-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0619-0 To the memory of MAMA NGWENGEH and MAMA FEHKIEUH CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgement ...................................................................................... xi List of Objects .......................................................................................... xiii List of Tables ........................................................................................... xvii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 7 The Name, Geography, Location and History Geographical Location History Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

CAMEROON: North-West and South-West Situation Report No

CAMEROON: North-West and South-West Situation Report No. 12 As of 31 October 2019 This report is produced by OCHA Cameroon in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers 1 – 31 October 2019. The next report will be issued in December. HIGHLIGHTS • 172,372 people benefitted from food and livelihood assistance in October. • 3,136 children received vitamin A and 950 children were vaccinated against measles in October • 112,794 individuals were reached with WASH activities during the reporting period. • 77,510 people have been reached with shelter assistance and 84,895 people have been supported with NFI assistance in the North-West and South-West (NWSW) since January. • 91% of school-aged children are out of school. • The total level of displacement from NWSW stands at over 700,000, including those displaced as refugees in Nigeria as well as in other regions in Cameroon. • Both parties to the conflict continue to breach International Law, including International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law, attacking civilians, schools and civilian health facilities. The health facility in Tole (SW) was destroyed by NSAGs after being used as a base by the Cameroon military. • Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs) as well as criminal groups continue to block humanitarian access with kidnapping of 10 humanitarian workers in October (all released) and demands for ransom are common. Source: OCHA The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on • 1,790 protection incidents were registered in October. Burning of this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the houses predominantly associated with Cameroon military represents United Nations.