SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN MIND March/April 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relative Value of Alcohol May Be Encoded by Discrete Regions of the Brain, According to a Study of 24 Men Published This Week in Neuropsychopharmacology

PRESS RELEASE FROM NEUROPSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY (http://www.nature.com/npp) This press release is copyrighted to the journal Neuropsychopharmacology. Its use is granted only for journalists and news media receiving it directly from the Nature Publishing Group. *** PLEASE DO NOT REDISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT *** EMBARGO: 1500 London time (GMT) / 1000 US Eastern Time Monday 03 March 2014 0000 Japanese time / 0200 Australian Eastern Time Tuesday 04 March 2014 Wire services’ stories must always carry the embargo time at the head of each item, and may not be sent out more than 24 hours before that time. Solely for the purpose of soliciting informed comment on this paper, you may show it to independent specialists - but you must ensure in advance that they understand and accept the embargo conditions. This press release contains: • Summaries of newsworthy papers: Brain changes in young smokers *PODCAST* To drink or not to drink? *PODCAST* • Geographical listing of authors PDFs of the papers mentioned on this release can be found in the Academic Journals section of the press site: http://press.nature.com Warning: This document, and the papers to which it refers, may contain sensitive or confidential information not yet disclosed to the public. Using, sharing or disclosing this information to others in connection with securities dealing or trading may be a violation of insider trading under the laws of several countries, including, but not limited to, the UK Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 and the US Securities Exchange Act of 1934, each of which may be subject to penalties and imprisonment. PICTURES: While we are happy for images from Neuropsychopharmacology to be reproduced for the purposes of contemporaneous news reporting, you must also seek permission from the copyright holder (if named) or author of the research paper in question (if not). -

Music, the Brain and Being Human

Gustavus/Howard Hughes Medical Institute Outreach Program 2011 Curriculum Materials ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Music, the Brain and Being Human Document Overview: Lesson plan Music survey handout The Brain and Music handout Minnesota State Science Standards: 9.1.1.1.2 Understand that scientists conduct investigations for a variety of reasons, including: to discover new aspects of the natural world, to explain observed phenomena, to test the conclusions of prior investigations, or to test the predictions of current theories. 9.1.1.1.3 Explain how societal and scientific ethics impact research practices. Objectives: ● Introduce students to how the brain is part of everyday life processes ● Show relationship between music and brain functions ● Describe relevance of neuroscience to the study of human behavior ● Spark student interest in the study and general field of neuroscience in preparation for future lessons Type of Activity: Multimedia, interactive discussion, writing, observation and interpretation of phenomena, inquiry Duration: 90 minutes, but can be easily modified for any time frame Connection to Nobel speaker: Speaker: Vilayanur Ramachandran, Director of the Center for Brain and Cognition and Professor, Psychology Department and Neuroscience Program -

Australian Music & Psychology Society Newsletter

Australian Music & Psychology Society March, 2016 Edition 2 Australian Music & Psychology Society Newsletter Welcome to our second edition After a slight delay, we are delighted to be able to bring this second edition of the AMPS newsletter to you. This newsletter is a student led publication, to facilitate discussion within the AMPS membership, and to provide a forum for researchers to write about any Inside this issue topics which may take their fancy. Music an antidote for aging? ...... 2 This issue contains some exciting submissions, including summaries of music and neuro- In Memory of Oliver Sacks .......... 3 science, the protective effect of music against cognitive aging, and a book review. We also have an obituary to Oliver Sacks, a prominent neurologist and advocate for music New AMPS Committee ................ 3 psychology. Many of the articles feature hyperlinks and web addresses, so you can access Book Review ............................... 4 additional material, or delve more deeply into this research by exploring web content if Rhythm Tracker .......................... 4 you wish. Music and Neuroscience ............. 5 This is also the last issue that Joanne Ruksenas has worked on as editor-in-chief. All of us on the AMPS Newsletter team would like to thank her for her hard work in putting Music Trust Research Award ....... 6 together this publication, and wish her all the best on her next project! Upcoming Conferences ............... 6 For future editions, please send original articles of scholarly research, book and perfor- AMPS2016 review ....................... 7 mance reviews, discussions of current research, and other items relating to music psy- About AMPS ................................ 8 chology. All are warmly welcomed. -

Spring 2009 Curriculum

Spring 2009 Curriculum ART HISTORY AH2102.01 Fashion and Modernism Josh Blackwell “Let There Be Fashion, Down With Art” –Max Ernst Fashion acts as a powerful analogue to and forecaster of Modernism's rise. Artists such as Matisse, Balla, Bakst, Delaunay and Dali took note of fashion's nascent agency and created clothing as a means of engaging the new political, social and cultural landscapes of the 20th Century. Influenced by Charles Baudelaire's radical questioning of beauty and fashion, artists attempted to define fashion’s role in culture, manipulating it to reflect their own proclivities. This seminar will consider various movements such as Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism, Constructivism, Dada, and Surrealism through the lens of fashion, investigating the various agendas and ideologies deployed. Culminating in the creation of original garments, students will engage the political spectrum as it intersects with Modernism's aesthetic partisanship. Regular assignments will include reading, visual research, and critical analysis of the material. A high degree of motivation is expected. Prerequisites: None. Credits: 2 Time: W 2:10 - 6pm (This course meets the second seven weeks of the term.) AH4101.01 Thematic Exposure Andrew Spence Taking a cue from recent exhibitions in art museums, art galleries, auction houses as well as trade show exhibits of antiques, design, cars, boats and art fairs, exhibition organizers and artists are interested in merging pluralistic elements of our culture into one big inclusive and broader based experience. Students in this class take a closer look at this development by selecting their own group of "things from anywhere" and presenting them in a meaningful way by producing a catalog for a hypothetical exhibition. -

Classical Net Review

The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source BOOK REVIEW The Psychology of Music Diana Deutsch, editor Academic Press, Third Edition, 2013, pp xvii + 765 ISBN-10: 012381460X ISBN-13: 978-0123814609 The psychology of music was first explored in detail in modern times in a book of that name by Carl E. Seashore… Psychology Of Music was published in 1919. Dover's paperback edition of almost 450 pages (ISBN- 10: 0486218511; ISBN-13: 978-0486218519) is still in print from half a century later (1967) and remains a good starting point for those wishing to understand the relationship between our minds and music, chiefly as a series of physical processes. From the last quarter of the twentieth century onwards much research and many theories have changed the models we have of the mind when listening to or playing music. Changes in music itself, of course, have dictated that the nature of human interaction with it has grown. Unsurprisingly, books covering the subject have proliferated too. These range from examinations of how memory affects our experience of music through various forms of mental disabilities, therapies and deviations from "standard" auditory reception, to attempts to explain music appreciation psychologically. Donald Hodges' and David Conrad Sebald's Music in the Human Experience: An Introduction to Music Psychology (ISBN-10: 0415881862; ISBN-13: 978- 0415881869) makes a good introduction to the subject; while Aniruddh Patel's Music, Language, and the Brain (ISBN-10: 0199755302; ISBN-13: 978-0199755301) is a good (and now classic/reference) overview. Oliver Sacks' Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain (ISBN-10: 1400033535; ISBN-13: 978-1400033539) examines specific areas from a clinical perspective. -

Antidepressants During Pregnancy and Fetal Development

PRESS RELEASE FROM NEUROPSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY (http://www.nature.com/npp) This press release is copyrighted to the journal Neuropsychopharmacology. Its use is granted only for journalists and news media receiving it directly from the Nature Publishing Group. *** PLEASE DO NOT REDISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT *** EMBARGO: 1500 London time (BST) / 1000 US Eastern Time / 2300 Japanese time Monday 19 May 2014 0000 Australian Eastern Time Tuesday 20 May 2014 Wire services’ stories must always carry the embargo time at the head of each item, and may not be sent out more than 24 hours before that time. Solely for the purpose of soliciting informed comment on this paper, you may show it to independent specialists - but you must ensure in advance that they understand and accept the embargo conditions. A PDF of the paper mentioned on this release can be found in the Academic Journals section of the press site: http://press.nature.com Warning: This document, and the papers to which it refers, may contain sensitive or confidential information not yet disclosed to the public. Using, sharing or disclosing this information to others in connection with securities dealing or trading may be a violation of insider trading under the laws of several countries, including, but not limited to, the UK Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 and the US Securities Exchange Act of 1934, each of which may be subject to penalties and imprisonment. PICTURES: While we are happy for images from Neuropsychopharmacology to be reproduced for the purposes of contemporaneous news reporting, you must also seek permission from the copyright holder (if named) or author of the research paper in question (if not). -

Advertising (PDF)

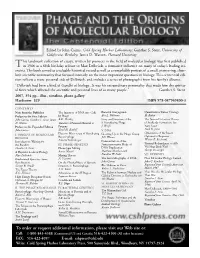

Edited by John Cairns, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Gunther S. Stent, University of California, Berkeley; James D. Watson, Harvard University his landmark collection of essays, written by pioneers in the field of molecular biology, was first published T in 1966 as a 60th birthday tribute to Max Delbrück, a formative influence on many of today’s leading sci- entists. The book served as a valuable historical record as well as a remarkable portrait of a small, pioneering, close- knit scientific community that focused intensely on the most important questions in biology. This centennial edi- tion reflects a more personal side of Delbrück, and includes a series of photographs from his family’s albums. “Delbrück had been a kind of Gandhi of biology...It was his extraordinary personality that made him the spiritu- al force which affected the scientific and personal lives of so many people.” —Gunther S. Stent 2007, 394 pp., illus., timeline, photo gallery Hardcover $29 ISBN 978-087969800-3 CONTENTS Note from the Publisher The Injection of DNA into Cells Bacterial Conjugation Quantitatitve Tumor Virology Preface to the First Edition by Phage Elie L. Wollman H. Rubin John Cairns, Gunther S. Stent, James A.D. Hershey Story and Structure of the The Natural Selection Theory D. Watson Transfer of Parental Material to λ Transducing Phage of Antibody Formation; Ten Preface to the Expanded Edition Progeny J. Weigle Years Later John Cairns Lloyd M. Kozloff V. DNA Niels K. Jerne Electron Microscopy of Developing Growing Up in the Phage Group Cybernetics of the Insect I. ORIGINS OF MOLECULAR Optomotor Response BIOLOGY Bacteriophage J.D. -

Effects of Emergent-Level Structure on Melodic Processing Difficulty

96 Frank A. Russo, William Forde Thompson, & Lola L. Cuddy EFFECTS OF EMERGENT-LEVEL STRUCTURE ON MELODIC PROCESSING DIFFICULTY FRANK A. RUSSO words, does ease of processing depend in some manner Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada on emergent-level structure defined by theory? The current study investigates whether melodic processing WILLIAM FORDE THOMPSON difficulty varies with respect to music-theoretic descrip- Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia tions of emergent-level structure derived from the Implication-Realization (I-R) model (Narmour, 1990, LOLA L. CUDDY 1992). Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada Two leading cognitive approaches to understanding melodic complexity include information-theoretic and FOUR EXPERIMENTS ASSESSED THE INFLUENCE dynamic attending models. Information-theoretic mod- of emergent-level structure on melodic processing dif- els have focused on the development of coding systems ficulty. Emergent-level structure was manipulated (Cuddy, Cohen, & Mewhort, 1981; Deutsch, 1980; Leeu- across experiments and defined with reference to the wenberg, 1969; Restle, 1970; Simon, 1972). A hierarchi- Implication-Realization model of melodic expectancy cal melody with surface- and emergent-level structure (Narmour, 1990, 1992, 2000). Two measures of melodic can be described economically using nested codes that processing difficulty were used to assess the influence of exploit redundancies. The codes are assumed to capture emergent-level structure: serial-reconstruction and important aspects of mental representation, and -

July/Aug 2002

ISSN 1473-9348 Volume 2 Issue 3 July/August 2002 ACNR Advances in Clinical Neuroscience & Rehabilitation journal reviews • events • management topic • industry news • rehabilitation topic Review Article: Neurological associations of coeliac disease Interview: Dr Oliver Sacks & Dr Paul Cox - The Parkinsonism dementia complex of Guam and flying foxes Rehabilitation Article: Mood and affective problems after traumatic brain injury COPAXONE® WORKS, DAY AFTER DAY, MONTH AFTER MONTH,YEAR AFTER YEAR Disease modifying therapy for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis Reduces relapse rates1 Maintains efficacy in the long-term1 Unique MS specific mode of action2 Reduces disease activity and burden of disease3 Well-tolerated, encourages long-term compliance1 (glatiramer acetate) Confidence in the future Section COPAXONE® (glatiramer acetate) PRESCRIBING INFORMA- TION Editorial Board and Presentation regular contributors Glatiramer acetate 20mg powder for solution with water for injection. Indication Roger Barker is co-editor in chief of Advances in Reduction of frequency of relapses in relapsing-remitting multiple Clinical Neuroscience & Rehabilitation (ACNR), and is sclerosis in ambulatory patients who have had at least one relapse in Honorary Consultant in Neurology at The Cambridge Centre for Brain Repair. He trained in neurology at the preceding two years before initiation of therapy. Cambridge and at the National Hospital in London. Dosage and administration His main area of research is into neurodegenerative 20mg of glatiramer acetate in 1 ml water for injection, administered and movement disorders, in particular parkinson's and sub-cutaneously once daily. Initiation to be supervised by neurologist Huntington's disease. He is also the university lecturer in Neurology or experienced physician. Supervise first self-injection and for 30 at Cambridge where he continues to develop his clinical research minutes after. -

University of Tartu Sign Systems Studies

University of Tartu Sign Systems Studies 32 Sign Systems Studies 32.1/2 Тартуский университет Tartu Ülikool Труды по знаковым системам Töid märgisüsteemide alalt 32.1/2 University of Tartu Sign Systems Studies volume 32.1/2 Editors: Peeter Torop Mihhail Lotman Kalevi Kull M TARTU UNIVERSITY I PRESS Tartu 2004 Sign Systems Studies is an international journal of semiotics and sign processes in culture and nature Periodicity: one volume (two issues) per year Official languages: English and Russian; Estonian for abstracts Established in 1964 Address of the editorial office: Department of Semiotics, University of Tartu Tiigi St. 78, Tartu 50410, Estonia Information and subscription: http://www.ut.ee/SOSE/sss.htm Assistant editor: Silvi Salupere International editorial board: John Deely (Houston, USA) Umberto Eco (Bologna, Italy) Vyacheslav V. Ivanov (Los Angeles, USA, and Moscow, Russia) Julia Kristeva (Paris, France) Winfried Nöth (Kassel, Germany, and Sao Paulo, Brazil) Alexander Piatigorsky (London, UK) Roland Posner (Berlin, Germany) Eero Tarasti (Helsinki, Finland) t Thure von Uexküll (Freiburg, Germany) Boris Uspenskij (Napoli, Italy) Irina Avramets (Tartu, Estonia) Jelena Grigorjeva (Tartu, Estonia) Ülle Pärli (Tartu, Estonia) Anti Randviir (Tartu, Estonia) Copyright University of Tartu, 2004 ISSN 1406-4243 Tartu University Press www.tyk.ut.ee Sign Systems Studies 32.1/2, 2004 Table of contents John Deely Semiotics and Jakob von Uexkiill’s concept of um welt .......... 11 Семиотика и понятие умвельта Якоба фон Юксюолла. Резюме ...... 33 Semiootika ja Jakob von Uexkülli omailma mõiste. Kokkuvõte ............ 33 Torsten Rüting History and significance of Jakob von Uexküll and of his institute in Hamburg ......................................................... 35 Якоб фон Юкскюлл и его институт в Гамбурге: история и значение. -

Journal Holdings 2019-2020

PONCE HEALTH SCIENCES UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Databases with Full Text Online: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z JOURNAL HOLDINGS 2019-2020 TITLE VOLUME YEAR ONLINE ACCESS AADE in Practice V.1- 2013- Sage AAP News 1985- ACP Journal Club V.136- 2002- Medline complete AJIC American Journal of Infection Control V.23- 1995- OVID AJN American Journal of Nursing V. 23- 1996- OVID AJR :American Journal of Roentgenology V. 95- 1965- Free Access(12mo.delay) ACIMED V.1- 1993- SciELO Academia de Médicos de Familia V.1-21. 1988-2009. Academic Emergency Medicine V.1- 1994- Ebsco Academic Medicine V.36- 1961- OVID Academic Pediatrics V. 9- 2009- ClinicalKey Academic Psychiatry V.21- 1997- Ebsco Acta Bioethica V.6- 2000- SciELO Acta Medica Colombiana V.30- 2005- SciELO Acta Medica Costarricense V.37- 1995- Free access Acta Medica Peruana V.23- 2006- Free access Page 1 Back to Top ↑ TITLE VOLUME YEAR ONLINE ACCESS Acta Pharmacologica Sinica V. 26- 2005- Nature.com Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría V. 29- 2001- Medline complete Action Research V. 1- 2003- Sage Adicciones V.11- 1999- Free access V.88- 1993- Medline complete (12 mo. Addiction delay) Addictive Behaviors V. 32- 2007- ClinicalKey Advances in Anatomic Pathology V.8- 2001- Ovid Advances in Immunology V.72-128. 1999- Science Direct Advances in Nutrition V.1- 2010-2015. Free access (12 mo. delay) Advances in Physiology Education V.256#6- 1989- Advances in Surgery V.41- 2007- Clinical Key The Aesculapian V.1. -

SPRINGER NATURE Products, Services & Solutions 2 Springer Nature Products, Services & Solutions Springernature.Com

springernature.com Illustration inspired by the work of Marie Curie SPRINGER NATURE Products, Services & Solutions 2 Springer Nature Products, Services & Solutions springernature.com About Springer Nature Springer Nature advances discovery by publishing robust and insightful research, supporting the development of new areas of knowledge, making ideas and information accessible around the world, and leading the way on open access. Our journals, eBooks, databases and solutions make sure that researchers, students, teachers and professionals have access to important research. Springer Established in 1842, Springer is a leading global scientific, technical, medical, humanities and social sciences publisher. Providing researchers with quality content via innovattive products and services, Springer has one of the most significant science eBooks and archives collections, as well as a comprehensive range of hybrid and open access journals. Nature Research Publishing some of the most significant discoveries since 1869. Nature Research publishes the world’s leading weekly science journal, Nature, in addition to Nature- branded research and review subscription journals. The portfolio also includes Nature Communications, the leading open access journal across all sciences, plus a variety of Nature Partner Journals, developed with institutions and societies. Academic journals on nature.com Prestigious titles in the clinical, life and physical sciences for communities and established medical and scientific societies, many of which are published in partnership a society. Adis A leading international publisher of drug-focused content and solutions. Adis supports work in the pharmaceutical and biotech industry, medical research, practice and teaching, drug regulation and reimbursement as well as related finance and consulting markets. Apress A technical publisher of high-quality, practical content including over 3000 titles for IT professionals, software developers, programmers and business leaders around the world.