How a Mathematician Started Making Movies 185

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Artistic and Mathematical Look at the Work of Maurits Cornelis Escher

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Honors Program Theses Honors Program 2016 Tessellations: An artistic and mathematical look at the work of Maurits Cornelis Escher Emily E. Bachmeier University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2016 Emily E. Bachmeier Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/hpt Part of the Harmonic Analysis and Representation Commons Recommended Citation Bachmeier, Emily E., "Tessellations: An artistic and mathematical look at the work of Maurits Cornelis Escher" (2016). Honors Program Theses. 204. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/hpt/204 This Open Access Honors Program Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: TESSELLATIONS: THE WORK OF MAURITS CORNELIS ESCHER TESSELLATIONS: AN ARTISTIC AND MATHEMATICAL LOOK AT THE WORK OF MAURITS CORNELIS ESCHER A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Designation University Honors Emily E. Bachmeier University of Northern Iowa May 2016 TESSELLATIONS : THE WORK OF MAURITS CORNELIS ESCHER This Study by: Emily Bachmeier Entitled: Tessellations: An Artistic and Mathematical Look at the Work of Maurits Cornelis Escher has been approved as meeting the thesis or project requirements for the Designation University Honors. ___________ ______________________________________________________________ Date Dr. Catherine Miller, Honors Thesis Advisor, Math Department ___________ ______________________________________________________________ Date Dr. Jessica Moon, Director, University Honors Program TESSELLATIONS : THE WORK OF MAURITS CORNELIS ESCHER 1 Introduction I first became interested in tessellations when my fifth grade mathematics teacher placed multiple shapes that would tessellate at the front of the room and we were allowed to pick one to use to create a tessellation. -

The Relative Value of Alcohol May Be Encoded by Discrete Regions of the Brain, According to a Study of 24 Men Published This Week in Neuropsychopharmacology

PRESS RELEASE FROM NEUROPSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY (http://www.nature.com/npp) This press release is copyrighted to the journal Neuropsychopharmacology. Its use is granted only for journalists and news media receiving it directly from the Nature Publishing Group. *** PLEASE DO NOT REDISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT *** EMBARGO: 1500 London time (GMT) / 1000 US Eastern Time Monday 03 March 2014 0000 Japanese time / 0200 Australian Eastern Time Tuesday 04 March 2014 Wire services’ stories must always carry the embargo time at the head of each item, and may not be sent out more than 24 hours before that time. Solely for the purpose of soliciting informed comment on this paper, you may show it to independent specialists - but you must ensure in advance that they understand and accept the embargo conditions. This press release contains: • Summaries of newsworthy papers: Brain changes in young smokers *PODCAST* To drink or not to drink? *PODCAST* • Geographical listing of authors PDFs of the papers mentioned on this release can be found in the Academic Journals section of the press site: http://press.nature.com Warning: This document, and the papers to which it refers, may contain sensitive or confidential information not yet disclosed to the public. Using, sharing or disclosing this information to others in connection with securities dealing or trading may be a violation of insider trading under the laws of several countries, including, but not limited to, the UK Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 and the US Securities Exchange Act of 1934, each of which may be subject to penalties and imprisonment. PICTURES: While we are happy for images from Neuropsychopharmacology to be reproduced for the purposes of contemporaneous news reporting, you must also seek permission from the copyright holder (if named) or author of the research paper in question (if not). -

De Divino Errore ‘De Divina Proportione’ Was Written by Luca Pacioli and Illustrated by Leonardo Da Vinci

De Divino Errore ‘De Divina Proportione’ was written by Luca Pacioli and illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci. It was one of the most widely read mathematical books. Unfortunately, a strongly emphasized statement in the book claims six summits of pyramids of the stellated icosidodecahedron lay in one plane. This is not so, and yet even extensively annotated editions of this book never noticed this error. Dutchmen Jos Janssens and Rinus Roelofs did so, 500 years later. Fig. 1: About this illustration of Leonardo da Vinci for the Milanese version of the ‘De Divina Proportione’, Pacioli erroneously wrote that the red and green dots lay in a plane. The book ‘De Divina Proportione’, or ‘On the Divine Ratio’, was written by the Franciscan Fra Luca Bartolomeo de Pacioli (1445-1517). His name is sometimes written Paciolo or Paccioli because Italian was not a uniform language in his days, when, moreover, Italy was not a country yet. Labeling Pacioli as a Tuscan, because of his birthplace of Borgo San Sepolcro, may be more correct, but he also studied in Venice and Rome, and spent much of his life in Perugia and Milan. In service of Duke and patron Ludovico Sforza, he would write his masterpiece, in 1497 (although it is more correct to say the work was written between 1496 and 1498, because it contains several parts). It was not his first opus, because in 1494 his ‘Summa de arithmetic, geometrica, proportioni et proportionalita’ had appeared; the ‘Summa’ and ‘Divina’ were not his only books, but surely the most famous ones. For hundreds of years the books were among the most widely read mathematical bestsellers, their fame being only surpassed by the ‘Elements’ of Euclid. -

The Creative Act in the Dialogue Between Art and Mathematics

mathematics Article The Creative Act in the Dialogue between Art and Mathematics Andrés F. Arias-Alfonso 1,* and Camilo A. Franco 2,* 1 Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, Universidad de Manizales, Manizales 170003, Colombia 2 Grupo de Investigación en Fenómenos de Superficie—Michael Polanyi, Departamento de Procesos y Energía, Facultad de Minas, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Medellín, Medellín 050034, Colombia * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.F.A.-A.); [email protected] (C.A.F.) Abstract: This study was developed during 2018 and 2019, with 10th- and 11th-grade students from the Jose Maria Obando High School (Fredonia, Antioquia, Colombia) as the target population. Here, the “art as a method” was proposed, in which, after a diagnostic, three moments were developed to establish a dialogue between art and mathematics. The moments include Moment 1: introduction to art and mathematics as ways of doing art, Moment 2: collective experimentation, and Moment 3: re-signification of education as a model of experience. The methodology was derived from different mathematical-based theories, such as pendulum motion, centrifugal force, solar energy, and Chladni plates, allowing for the exploration of possibilities to new paths of knowledge from proposing the creative act. Likewise, the possibility of generating a broad vision of reality arose from the creative act, where understanding was reached from logical-emotional perspectives beyond the rational vision of science and its descriptions. Keywords: art; art as method; creative act; mathematics 1. Introduction Citation: Arias-Alfonso, A.F.; Franco, C.A. The Creative Act in the Dialogue There has always been a conception in the collective imagination concerning the between Art and Mathematics. -

Mathematics K Through 6

Building fun and creativity into standards-based learning Mathematics K through 6 Ron De Long, M.Ed. Janet B. McCracken, M.Ed. Elizabeth Willett, M.Ed. © 2007 Crayola, LLC Easton, PA 18044-0431 Acknowledgements Table of Contents This guide and the entire Crayola® Dream-Makers® series would not be possible without the expertise and tireless efforts Crayola Dream-Makers: Catalyst for Creativity! ....... 4 of Ron De Long, Jan McCracken, and Elizabeth Willett. Your passion for children, the arts, and creativity are inspiring. Thank you. Special thanks also to Alison Panik for her content-area expertise, writing, research, and curriculum develop- Lessons ment of this guide. Garden of Colorful Counting ....................................... 6 Set representation Crayola also gratefully acknowledges the teachers and students who tested the lessons in this guide: In the Face of Symmetry .............................................. 10 Analysis of symmetry Barbi Bailey-Smith, Little River Elementary School, Durham, NC Gee’s-o-metric Wisdom ................................................ 14 Geometric modeling Rob Bartoch, Sandy Plains Elementary School, Baltimore, MD Patterns of Love Beads ................................................. 18 Algebraic patterns Susan Bivona, Mount Prospect Elementary School, Basking Ridge, NJ A Bountiful Table—Fair-Share Fractions ...................... 22 Fractions Jennifer Braun, Oak Street Elementary School, Basking Ridge, NJ Barbara Calvo, Ocean Township Elementary School, Oakhurst, NJ Whimsical Charting and -

August 1995 Council Minutes

AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY COUNCIL MINUTES Burlington, Vermont 05 August 1995 Abstract The Council of the American Mathematical Society met at 1:00 p.m. on Satur- day, 05 August 1995, in the Emerald Grand Ballroom in the Sheraton Burlington, Burlington, Vermont. These are the minutes for the meeting. Members present were Georgia Benkart, Joan Birman, Robert Daverman (vot- ing Associate Secretary), David Epstein, Robert Fossum, John Franks, Ron Gra- ham, Steven Krantz, Andy Magid (Associate Secretary), Cathleen Morawetz, Frank Morgan, Franklin Peterson, Marc Rieffel, Cora Sadosky, Norberto Salinas, Peter Shalen, Lesley Sibner (Associate Secretary), B. A. Taylor, Jean Taylor, and Sylvia Wiegand. Staff and others invited to attend were Don Babbitt (Publisher), Annalisa Cran- nell (Committee on the Profession Representative), Chandler Davis (Canadian Mathematical Society Representative), John Ewing (Executive Director), Tim Gog- gins (Development Officer), Carolyn Gordon (Editorial Boards Committee Repre- sentative), Jim Lewis (Committee on Science Policy Chair), James Maxwell (AED), Don McClure (Trustee), Susan Montgomery (Trustee), Everett Pitcher (Former Secretary), Sam Rankin (AED), and Kelly Young (Assistant to the Secretary). President Morawetz presided. 1 2 CONTENTS Contents IAGENDA 4 0 CALL TO ORDER AND INTRODUCTIONS. 4 1MINUTES 4 1.1March95Council...................................... 4 1.2 05/95 Meeting of the Executive Committee and Board of Trustees. 4 2 CONSENT AGENDA. 4 2.1Resolutions......................................... 4 2.1.1 Exxon Foundation. ......................... 4 2.2CommitteeAdministration................................ 5 2.2.1 Dischargewiththanks............................... 5 2.2.2 CommitteeCharges................................ 5 3 REPORTS OF BOARDS AND STANDING COMMITTEES. 5 3.1 EDITORIAL BOARDS COMMITTEE (EBC). .................. 5 3.1.1 TransactionsandMemoirsEditorialCommittee................. 5 3.1.2 Journal of the AMS . -

Density of Algebraic Points on Noetherian Varieties 3

DENSITY OF ALGEBRAIC POINTS ON NOETHERIAN VARIETIES GAL BINYAMINI Abstract. Let Ω ⊂ Rn be a relatively compact domain. A finite collection of real-valued functions on Ω is called a Noetherian chain if the partial derivatives of each function are expressible as polynomials in the functions. A Noether- ian function is a polynomial combination of elements of a Noetherian chain. We introduce Noetherian parameters (degrees, size of the coefficients) which measure the complexity of a Noetherian chain. Our main result is an explicit form of the Pila-Wilkie theorem for sets defined using Noetherian equalities and inequalities: for any ε> 0, the number of points of height H in the tran- scendental part of the set is at most C ·Hε where C can be explicitly estimated from the Noetherian parameters and ε. We show that many functions of interest in arithmetic geometry fall within the Noetherian class, including elliptic and abelian functions, modular func- tions and universal covers of compact Riemann surfaces, Jacobi theta func- tions, periods of algebraic integrals, and the uniformizing map of the Siegel modular variety Ag . We thus effectivize the (geometric side of) Pila-Zannier strategy for unlikely intersections in those instances that involve only compact domains. 1. Introduction 1.1. The (real) Noetherian class. Let ΩR ⊂ Rn be a bounded domain, and n denote by x := (x1,...,xn) a system of coordinates on R . A collection of analytic ℓ functions φ := (φ1,...,φℓ): Ω¯ R → R is called a (complex) real Noetherian chain if it satisfies an overdetermined system of algebraic partial differential equations, i =1,...,ℓ ∂φi = Pi,j (x, φ), (1) ∂xj j =1,...,n where P are polynomials. -

Simple Rules for Incorporating Design Art Into Penrose and Fractal Tiles

Bridges 2012: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Simple Rules for Incorporating Design Art into Penrose and Fractal Tiles San Le SLFFEA.com [email protected] Abstract Incorporating designs into the tiles that form tessellations presents an interesting challenge for artists. Creating a viable M.C. Escher-like image that works esthetically as well as functionally requires resolving incongruencies at a tile’s edge while constrained by its shape. Escher was the most well known practitioner in this style of mathematical visualization, but there are significant mathematical objects to which he never applied his artistry including Penrose Tilings and fractals. In this paper, we show that the rules of creating a traditional tile extend to these objects as well. To illustrate the versatility of tiling art, images were created with multiple figures and negative space leading to patterns distinct from the work of others. 1 1 Introduction M.C. Escher was the most prominent artist working with tessellations and space filling. Forty years after his death, his creations are still foremost in people’s minds in the field of tiling art. One of the reasons Escher continues to hold such a monopoly in this specialty are the unique challenges that come with creating Escher type designs inside a tessellation[15]. When an image is drawn into a tile and extends to the tile’s edge, it introduces incongruencies which are resolved by continuously aligning and refining the image. This is particularly true when the image consists of the lizards, fish, angels, etc. which populated Escher’s tilings because they do not have the 4-fold rotational symmetry that would make it possible to arbitrarily rotate the image ± 90, 180 degrees and have all the pieces fit[9]. -

Antidepressants During Pregnancy and Fetal Development

PRESS RELEASE FROM NEUROPSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY (http://www.nature.com/npp) This press release is copyrighted to the journal Neuropsychopharmacology. Its use is granted only for journalists and news media receiving it directly from the Nature Publishing Group. *** PLEASE DO NOT REDISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT *** EMBARGO: 1500 London time (BST) / 1000 US Eastern Time / 2300 Japanese time Monday 19 May 2014 0000 Australian Eastern Time Tuesday 20 May 2014 Wire services’ stories must always carry the embargo time at the head of each item, and may not be sent out more than 24 hours before that time. Solely for the purpose of soliciting informed comment on this paper, you may show it to independent specialists - but you must ensure in advance that they understand and accept the embargo conditions. A PDF of the paper mentioned on this release can be found in the Academic Journals section of the press site: http://press.nature.com Warning: This document, and the papers to which it refers, may contain sensitive or confidential information not yet disclosed to the public. Using, sharing or disclosing this information to others in connection with securities dealing or trading may be a violation of insider trading under the laws of several countries, including, but not limited to, the UK Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 and the US Securities Exchange Act of 1934, each of which may be subject to penalties and imprisonment. PICTURES: While we are happy for images from Neuropsychopharmacology to be reproduced for the purposes of contemporaneous news reporting, you must also seek permission from the copyright holder (if named) or author of the research paper in question (if not). -

William M. Goldman June 24, 2021 CURRICULUM VITÆ

William M. Goldman June 24, 2021 CURRICULUM VITÆ Professional Preparation: Princeton Univ. A. B. 1977 Univ. Cal. Berkeley Ph.D. 1980 Univ. Colorado NSF Postdoc. 1980{1981 M.I.T. C.L.E. Moore Inst. 1981{1983 Appointments: I.C.E.R.M. Member Sep. 2019 M.S.R.I. Member Oct.{Dec. 2019 Brown Univ. Distinguished Visiting Prof. Sep.{Dec. 2017 M.S.R.I. Member Jan.{May 2015 Institute for Advanced Study Member Spring 2008 Princeton University Visitor Spring 2008 M.S.R.I. Member Nov.{Dec. 2007 Univ. Maryland Assoc. Chair for Grad. Studies 1995{1998 Univ. Maryland Professor 1990{present Oxford Univ. Visiting Professor Spring 1989 Univ. Maryland Assoc. Professor 1986{1990 M.I.T. Assoc. Professor 1986 M.S.R.I. Member 1983{1984 Univ. Maryland Visiting Asst. Professor Fall 1983 M.I.T. Asst. Professor 1983 { 1986 1 2 W. GOLDMAN Publications (1) (with D. Fried and M. Hirsch) Affine manifolds and solvable groups, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 3 (1980), 1045{1047. (2) (with M. Hirsch) Flat bundles with solvable holonomy, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 82 (1981), 491{494. (3) (with M. Hirsch) Flat bundles with solvable holonomy II: Ob- struction theory, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 83 (1981), 175{178. (4) Two examples of affine manifolds, Pac. J. Math.94 (1981), 327{ 330. (5) (with M. Hirsch) A generalization of Bieberbach's theorem, Inv. Math. , 65 (1981), 1{11. (6) (with D. Fried and M. Hirsch) Affine manifolds with nilpotent holonomy, Comm. Math. Helv. 56 (1981), 487{523. (7) Characteristic classes and representations of discrete subgroups of Lie groups, Bull. -

EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ROBIN WILSON Department of Pure Mathematics the Open University Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK E-Mail: [email protected]

CONTENTS EDITORIAL TEAM EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ROBIN WILSON Department of Pure Mathematics The Open University Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK e-mail: [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS VASILE BERINDE Department of Mathematics, University of Baia Mare, Romania e-mail: [email protected] NEWSLETTER No. 47 KRZYSZTOF CIESIELSKI Mathematics Institute March 2003 Jagiellonian University Reymonta 4 EMS Agenda ................................................................................................. 2 30-059 Kraków, Poland e-mail: [email protected] Editorial by Sir John Kingman .................................................................... 3 STEEN MARKVORSEN Department of Mathematics Executive Committee Meeting ....................................................................... 4 Technical University of Denmark Building 303 Introducing the Committee ............................................................................ 7 DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark e-mail: [email protected] An Answer to the Growth of Mathematical Knowledge? ............................... 9 SPECIALIST EDITORS Interview with Vagn Lundsgaard Hansen .................................................. 15 INTERVIEWS Steen Markvorsen [address as above] Interview with D V Anosov .......................................................................... 20 SOCIETIES Krzysztof Ciesielski [address as above] Israel Mathematical Union ......................................................................... 25 EDUCATION Tony Gardiner -

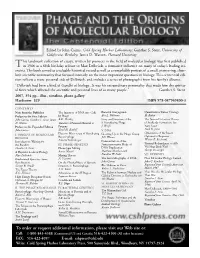

Advertising (PDF)

Edited by John Cairns, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Gunther S. Stent, University of California, Berkeley; James D. Watson, Harvard University his landmark collection of essays, written by pioneers in the field of molecular biology, was first published T in 1966 as a 60th birthday tribute to Max Delbrück, a formative influence on many of today’s leading sci- entists. The book served as a valuable historical record as well as a remarkable portrait of a small, pioneering, close- knit scientific community that focused intensely on the most important questions in biology. This centennial edi- tion reflects a more personal side of Delbrück, and includes a series of photographs from his family’s albums. “Delbrück had been a kind of Gandhi of biology...It was his extraordinary personality that made him the spiritu- al force which affected the scientific and personal lives of so many people.” —Gunther S. Stent 2007, 394 pp., illus., timeline, photo gallery Hardcover $29 ISBN 978-087969800-3 CONTENTS Note from the Publisher The Injection of DNA into Cells Bacterial Conjugation Quantitatitve Tumor Virology Preface to the First Edition by Phage Elie L. Wollman H. Rubin John Cairns, Gunther S. Stent, James A.D. Hershey Story and Structure of the The Natural Selection Theory D. Watson Transfer of Parental Material to λ Transducing Phage of Antibody Formation; Ten Preface to the Expanded Edition Progeny J. Weigle Years Later John Cairns Lloyd M. Kozloff V. DNA Niels K. Jerne Electron Microscopy of Developing Growing Up in the Phage Group Cybernetics of the Insect I. ORIGINS OF MOLECULAR Optomotor Response BIOLOGY Bacteriophage J.D.