3. Historical Comment and Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alan Turing, Computing, Bletchley, and Mathematics, Wellington Public

Alan Turing, Computing, Bletchley, and Mathematics Rod Downey Victoria University Wellington New Zealand Downey's research is supported by the Marsden Fund, and this material also by the Newton Institute. Wellington, February 2015 Turing I Turing has become a larger than life figure following the movie \The Imitation Game". I which followed Andrew Hodges book \Alan Turing : The Enigma", I which followed the release of classified documents about WWII. I I will try to comment on aspects of Turing's work mentioned in the movie. I I will give extensive references if you want to follow this up, including the excellent Horizon documentary. I Posted to my web site. Type \rod downey" into google. Turing Award I The equivalent of the \Nobel Prize" in computer science is the ACM Turing Award. I It is for life work in computer science and worth about $1M. I Why? This award was made up (1966) was well before Bletchley became public knowledge. I (Aside) Prof. D. Ritchie (Codebreaker)-from \Station X, Pt 3" Alan Turing was one of the figures of the century. || There were great men at Bletchley Park, but in the long hall of history Turing's name will be remembered as Number One in terms of consequences for mankind. Logic I Aristotle and other early Greeks then \modern" re-invention: Leibnitz (early 18th C), Boole, Frege, etc. I We want a way to represent arguments, language, processes etc by formal symbols and manipulate them like we do numbers to determine, e.g. validity of argument. I Simplest modern formal system propositional logic. -

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus the Secrets of Enigma

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus The Secrets of Enigma B. Jack Copeland, Editor OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS The Essential Turing Alan M. Turing The Essential Turing Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma Edited by B. Jack Copeland CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Taipei Toronto Shanghai With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan South Korea Poland Portugal Singapore Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © In this volume the Estate of Alan Turing 2004 Supplementary Material © the several contributors 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. -

OBITUARY 307 Obituary Sir Erik Christopher Zeeman FRS 1925–2016

OBITUARY 307 Obituary Sir Erik Christopher Zeeman FRS 1925–2016 Christopher Zeeman was born in Japan on 4 February 1925 to a Danish father, Christian, and British mother, Christine. When he was one year old, his parents moved to England. He was a pupil at the independent school Christ's Hospital, in Horsham, West Sussex. Between 1943 and 1947 he was a flying officer in the Royal Air Force. In a career change that was to have major impact on British mathematics, he studied the subject at Christ's College, Cambridge University, graduating with an MA degree. He then carried out research for a PhD at Cambridge, supervised by the topologist Shaun Wylie. His topic was an area of algebraic topology, which associates abstract algebraic structures (‘invariants’) to topological spaces in such a way that continuous maps between spaces induce structure-preserving maps between the corresponding algebraic structures. In this manner, questions about topology can be reduced to more tractable questions in algebra. His thesis combined two such invariants, homology and cohomology, which go back to the seminal work of Henri Poincaré at the start of the 20th century.* The result was named dihomology. He introduced an important technical tool to extract useful information from this set-up, now known as the Zeeman spectral sequence. His work led Robert MacPherson and Mark Goresky to invent the basic notion of intersection homology; these ideas in turn led to proofs of some major conjectures, including the Kazhdan–Lusztig conjectures in group representation theory and the Riemann–Hilbert correspondence for complex differential equations. -

Simply Turing

Simply Turing Simply Turing MICHAEL OLINICK SIMPLY CHARLY NEW YORK Copyright © 2020 by Michael Olinick Cover Illustration by José Ramos Cover Design by Scarlett Rugers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-943657-37-7 Brought to you by http://simplycharly.com Contents Praise for Simply Turing vii Other Great Lives x Series Editor's Foreword xi Preface xii Acknowledgements xv 1. Roots and Childhood 1 2. Sherborne and Christopher Morcom 7 3. Cambridge Days 15 4. Birth of the Computer 25 5. Princeton 38 6. Cryptology From Caesar to Turing 44 7. The Enigma Machine 68 8. War Years 85 9. London and the ACE 104 10. Manchester 119 11. Artificial Intelligence 123 12. Mathematical Biology 136 13. Regina vs Turing 146 14. Breaking The Enigma of Death 162 15. Turing’s Legacy 174 Sources 181 Suggested Reading 182 About the Author 185 A Word from the Publisher 186 Praise for Simply Turing “Simply Turing explores the nooks and crannies of Alan Turing’s multifarious life and interests, illuminating with skill and grace the complexities of Turing’s personality and the long-reaching implications of his work.” —Charles Petzold, author of The Annotated Turing: A Guided Tour through Alan Turing’s Historic Paper on Computability and the Turing Machine “Michael Olinick has written a remarkably fresh, detailed study of Turing’s achievements and personal issues. -

Responding to the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Business

THE 4TH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION Responding to the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Business MARK SKILTON & FELIX HOVSEPIAN The 4th Industrial Revolution “Unprecedented and simultaneous advances in artifcial intelligence (AI), robotics, the internet of things, autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, nanotechnology, bio- technology, materials science, energy storage, quantum computing and others are redefning industries, blurring traditional boundaries, and creating new opportuni- ties. We have dubbed this the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and it is fundamentally changing the way we live, work and relate to one another.” —Professor Klaus Schwab, 2016 Mark Skilton · Felix Hovsepian The 4th Industrial Revolution Responding to the Impact of Artifcial Intelligence on Business Mark Skilton Felix Hovsepian Warwick Business School Meriden, UK Knowle, Solihull, UK ISBN 978-3-319-62478-5 ISBN 978-3-319-62479-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62479-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017948314 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2018 Tis work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Te use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

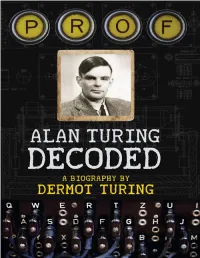

Profalanturing-Decoded-Biography

CONTENTS Title Introduction 1. Unreliable Ancestors 2. Dismal Childhoods 3. Direction of Travel 4. Kingsman 5. Machinery of Logic 6. Prof 7. Looking Glass War 8. Lousy Computer 9. Taking Shape 10. Machinery of Justice 11. Unseen Worlds Epilogue: Alan Turing Decoded Notes and Accreditations Copyright Blue Plaques in Hampton, Maida Vale, Manchester and Wilmslow. At Bletchley Park, where Alan Turing did the work for which he is best remembered, there is no plaque but a museum exhibition. INTRODUCTION ALAN TURING is now a household name, and in Britain he is a national hero. There are several biographies, a handful of documentaries, one Hollywood feature film, countless articles, plays, poems, statues and other tributes, and a blue plaque in almost every town where he lived or worked. One place which has no blue plaque is Bletchley Park, but there is an entire museum exhibition devoted to him there. We all have our personal image of Alan Turing, and it is easy to imagine him as a solitary, asocial genius who periodically presented the world with stunning new ideas, which sprang unaided and fully formed from his brain. The secrecy which surrounded the story of Bletchley Park after World War Two may in part be responsible for the commonly held view of Alan Turing. For many years the codebreakers were permitted only to discuss the goings-on there in general, anecdotal terms, without revealing any of the technicalities of their work. So the easiest things to discuss were the personalities, and this made good copy: eccentric boffins busted the Nazi machine. -

Enigma Peter Hilton

comm-hilton.qxp 4/22/98 10:00 AM Page 681 Book Review Enigma Peter Hilton Enigma London Sunday Times under the heading “The Robert Harris house that won the war”.) 320 pages It is in fact strange that, whereas the play by Random House Hugh Whitemore, while inspired by the life and $23.00 Hardcover work of Alan Turing, was a work of highly imag- inative dramatic fiction, Enigma, a work of The pretext—I would like to say “justification”— avowed fiction, recreates the atmosphere among for reviewing this book in a publication of the those engaged in code-breaking at Bletchley Park AMS must be that it is a novel explicitly based with remarkable fidelity. My own period of ser- on the effective use of mathematical method in vice at Bletchley Park began on January 12, 1942, the specific context of code-breaking in World and continued until shortly after the end of the War II. The author pays tribute to the inspired war in Europe. For the first year I was in Hut 8 work of a group of mathematicians—and one, in working on the U-boat Enigma code, so I partic- particular, Tom Jericho, disciple of Alan Tur- ipated in the milieu in which the action of this ing—in breaking the German U-boat Enigma code novel takes place. Early in 1943 I was transferred and thus enabling the Allies to win the battle of to work on the Geheimchreiber (or “Fish”, as we the Atlantic in 1943. If Hugh Whitemore de- irreverently called it), an even more sophisti- served the award he was given by JPBM for his cated machine which came to carry practically play “Breaking the Code”, dealing with the life all the highest-grade German cipher traffic. -

Bletchley Girl and Enigma: a Citation

The Wychwood December/January 2009/10 Vol30No5 Special Feature Bletchley Girl and Enigma: A Citation Miss Pauline Elliott, could sing madrigals, musician and Latin which she enjoyed scholar, has been and played the given a medal and Sorceress in a citation by Gordon production of Brown for her work Purcell’s Dido and at Bletchley Park Aeneas . Sometimes during the Second she went on her bike World War - but she to Milton Keynes. claims it is all a Pauline became mistake! Her sister friendly with the was an brilliant accomplished mathematicians, mathematician, and Hugh Alexander and was actively recruited to work at Shaun Wylie. Bletchley, however, her sister had just had a baby, and her husband was away, Code Broken but Lives Still Lost so Pauline went to Bletchley in her Alexander was Turing’s successor as sister’s place! head of Hut 8; Pauline adds that “only Pauline says she was good at languages, Turing made a bigger contribution to the and had excellent French and German, so success of Hut 8 than Wylie.” Pauline those were useful tools for her work with remained friendly with Hugh Alexander Naval Intelligence and she was able to after the war, and looked after him to his help with the wording of intercepted dying day. She and her sister were both messages. However, she modestly claims students at the Dragon School where she was not the mathematical brain they Shaun Wylie spotted Pauline’s sister’s really wanted to help Alan Turing break mathematical talents. the German Enigma code with his One of the high points in Pauline’s years Bombe machine. -

BREAKING NAVAL ENIGMA (DOLPHIN and SHARK) by Ralph Erskine

BREAKING NAVAL ENIGMA (DOLPHIN AND SHARK) by Ralph Erskine This note outlines the methods used by BP's Hut 8 to break naval Enigma. There can be little doubt that the naval Enigma decrypts helped to shorten the war, although it is not possible to give a precise period. The German Navy's three-rotor Enigma machine (M3) was identical to the model used by the German Army and Air Force, but it was supplied with three additional rotors, VI, VII and VIII, which were reserved exclusively for naval use. However, the German Navy also employed codebooks, which shortened signals as a precaution against shore high-frequency direction-finding, and some manual ciphers. The codebooks most often used were the Kurzsignalheft (short signal book) for reports such as sighting convoys, and the Wetterkurzschlüssel (weather short signal book) for weather reports. The relevant codegroups were super-enciphered on Enigma before being transmitted by radio. Naval Enigma signals used a number of different ciphers, each with its own daily key (rotor order, ring settings, plugboard connections and basic rotor setting). The principal cipher was Heimisch (known to BP as Dolphin), for U-boats and surface ships in home waters, including the Atlantic. At least 14 other naval Enigma ciphers were used during the war. Most ciphers had Allgemein (general) and Offizier keys. Offizier signals were first enciphered using the plugboard connections from monthly Offizier keylists. The complete message was then enciphered a second time using the Allgemein key. A few ciphers also had Stab (Staff) keys, which were also doubly enciphered, but had their own special settings. -

COLOSSUS Ooo O • O O Ooooooooooooooooooooooeoooooo O OOOO OO O OOO the Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers

COLOSSUS ooo o • o o ooooooooooooooooooooooeoooooo O OOOO OO O OOO The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers B.Jack Copeland and others (Edited by B.Jack Copeland) OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Contents List of Photographs x Notes on the Contributors xii Introduction 1 Jack Copeland SECTION 1. BLETCHLEY PARK AND THE ATTACK ON TUNNY 1. A Brief History of Cryptography from Caesar to Bletchley Park 9 Simon Singh 2. How It Began: Bletchley Park Goes to War 18 Michael Smith 3. The German Tunny Machine 36 Jack Copeland 4. Colossus, Codebreaking, and the Digital Age 52 Stephen Budiansky 5. Machine against Machine 64 Jack Copeland 6. D-Day at Bletchley Park 78 Thomas H. Flowers 7. Intercept! 84 Jack Copeland SECTION 2. COLOSSUS 8. Colossus 91 Thomas H. Flowers 9. Colossus and the Rise of the Modern Computer 101 Jack Copeland 10. The PC-User's Guide to Colossus 116 Benjamin Wells viii Contents 11. Of Men and Machines 141 Brian Randell 12. The Colossus Rebuild 150 Tony Sale SECTION 3. THENEWMANRY 13. Mr Newman's Section 157 Jack Copeland, with Catherine Caughey, Dorothy Du Boisson, Eleanor Ireland, Ken Myers, and Norman Thurlow 14. Max Newman—Mathematician, Codebreaker, and Computer Pioneer 176 William Newman 15. Living with Fish: Breaking Tunny in the Newmanry and the Testery 189 Peter Hilton 16. From Hut 8 to the Newmanry 204 Irving John (Jack) Good 17. Codebreaking and Colossus 223 Donald Michie SECTION 4. THE TESTERY 18. Major Tester's Section 249 Jerry Roberts 19. Setter and Breaker 260 Roy Jenkins 20. An ATS Girl in the Testery 264 Helen Currie 21. -

The Essential Turing : Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life, Plus

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus The Secrets of Enigma B. Jack Copeland, Editor OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS The Essential Turing Alan M. Turing The Essential Turing Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma Edited by B. Jack Copeland CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Taipei Toronto Shanghai With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan South Korea Poland Portugal Singapore Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © In this volume the Estate of Alan Turing 2004 Supplementary Material © the several contributors 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. -

COLLAPSE Charles R

AMS / MAA SPECTRUM VOL 76 SIX SOURCES OF COLLAPSE Charles R. Hadlock A MATHEMATICIAN’S PERSPECTIVE ON HOW THINGS CAN FALL APART IN THE BLINK OF AN EYE i i “master” — 2012/10/11 — 22:40 — page i — #1 i i 10.1090/spec/076 Six Sources of Collapse A Mathematician’s Perspective on How Things Can Fall Apart in the Blink of an Eye i i i i i i “master” — 2012/10/11 — 22:40 — page ii — #2 i i The photo of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge on the cover is used courtesy of UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Negative number: UW21418. c 2012 by the Mathematical Association of America, Inc. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2012950085 Print edition ISBN 978-0-88385-579-9 Electronic edition ISBN 978-1-61444-514-2 Printed in the United States of America Current Printing (last digit): 10987654321 i i i i i i “master” — 2012/10/11 — 22:40 — page iii — #3 i i Six Sources of Collapse A Mathematician’s Perspective on How Things Can Fall Apart in the Blink of an Eye Charles R. Hadlock Bentley University Published and Distributed by The Mathematical Association of America i i i i i i “master” — 2012/10/11 — 22:40 — page iv — #4 i i Council on Publications and Communications Frank Farris, Chair Committee on Books Gerald Bryce, Chair Spectrum Editorial Board Gerald L. Alexanderson, Co-Editor James J. Tattersall, Co-Editor Robert E. Bradley Susanna S. Epp RichardK.Guy KeithM.Kendig Shawnee L. McMurran Jeffrey L. Nunemacher Jean J.