Profalanturing-Decoded-Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2016 Apr 28th, 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology? Hayley A. LeBlanc Sunset High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y LeBlanc, Hayley A., "To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?" (2016). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2016/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. To what extent did British advancements in cryptanalysis during World War 2 influence the development of computer technology? Hayley LeBlanc 1936 words 1 Table of Contents Section A: Plan of Investigation…………………………………………………………………..3 Section B: Summary of Evidence………………………………………………………………....4 Section C: Evaluation of Sources…………………………………………………………………6 Section D: Analysis………………………………………………………………………………..7 Section E: Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………10 Section F: List of Sources………………………………………………………………………..11 Appendix A: Explanation of the Enigma Machine……………………………………….……...13 Appendix B: Glossary of Cryptology Terms.…………………………………………………....16 2 Section A: Plan of Investigation This investigation will focus on the advancements made in the field of computing by British codebreakers working on German ciphers during World War 2 (19391945). -

The Eagle 2005

CONTENTS Message from the Master .. .. .... .. .... .. .. .. .. .. .... ..................... 5 Commemoration of Benefactors .. .............. ..... ..... ....... .. 10 Crimes and Punishments . ................................................ 17 'Gone to the Wars' .............................................. 21 The Ex-Service Generations ......................... ... ................... 27 Alexandrian Pilgrimage . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .................. 30 A Johnian Caricaturist Among Icebergs .............................. 36 'Leaves with Frost' . .. .. .. .. .. .. ................ .. 42 'Chicago Dusk' .. .. ........ ....... ......... .. 43 New Court ........ .......... ....................................... .. 44 A Hidden Treasure in the College Library ............... .. 45 Haiku & Tanka ... 51 and sent free ...... 54 by St John's College, Cambridge, The Matterhorn . The Eagle is published annually and other interested parties. Articles members of St John's College .... 55 of charge to The Eagle, 'Teasel with Frost' ........... should be addressed to: The Editor, to be considered for publication CB2 1 TP. .. .. .... .. .. ... .. ... .. .. ... .... .. .. .. ... .. .. 56 St John's College, Cambridge, Trimmings Summertime in the Winter Mountains .. .. ... .. .. ... ... .... .. .. 62 St John's College Cambridge The Johnian Office ........... ..... .................... ........... ........... 68 CB2 1TP Book Reviews ........................... ..................................... 74 http:/ /www.joh.cam.ac.uk/ Obituaries -

Alan Turing's Automatic Computing Engine

5 Turing and the computer B. Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot The Turing machine In his first major publication, ‘On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem’ (1936), Turing introduced his abstract Turing machines.1 (Turing referred to these simply as ‘computing machines’— the American logician Alonzo Church dubbed them ‘Turing machines’.2) ‘On Computable Numbers’ pioneered the idea essential to the modern computer—the concept of controlling a computing machine’s operations by means of a program of coded instructions stored in the machine’s memory. This work had a profound influence on the development in the 1940s of the electronic stored-program digital computer—an influence often neglected or denied by historians of the computer. A Turing machine is an abstract conceptual model. It consists of a scanner and a limitless memory-tape. The tape is divided into squares, each of which may be blank or may bear a single symbol (‘0’or‘1’, for example, or some other symbol taken from a finite alphabet). The scanner moves back and forth through the memory, examining one square at a time (the ‘scanned square’). It reads the symbols on the tape and writes further symbols. The tape is both the memory and the vehicle for input and output. The tape may also contain a program of instructions. (Although the tape itself is limitless—Turing’s aim was to show that there are tasks that Turing machines cannot perform, even given unlimited working memory and unlimited time—any input inscribed on the tape must consist of a finite number of symbols.) A Turing machine has a small repertoire of basic operations: move left one square, move right one square, print, and change state. -

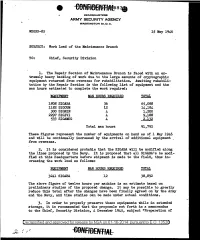

Work Load of the Maintenance Branch

HEADQUARTERS ARMY SECURITY AGENCY WASHINGTON 25, D. C. WDGSS-85 15 May 1946 SUBJECT: Work Load of the Maintenance Branch TO: Chief, Security Division 1. The Repair Section of Maintenance Branch is .faced with an ex tremely heavy backlog of' work due to the large amounts of' cryptographic equipment returned from overseas for rehabilitation. Awaiting rehabili tation by the Repair Section is the followi~g list of equipment and the man hours estimated to complete the work required.: EQUIPMENT MAN HOURS REQUIRED TOTAL 1808 SIGABA 36 65,088 1182 SIGCUM 12 14,184 300 SIGNIN 4 1,200 2297 SIGIVI 4 9,188 533 SIGAMUG 4, 2,132 Total man hours 91,792 These figures represent the number of equipments on hand as of 1 May 1946 and will be continually increased by the arrival of additional equipment . from overseas. 2. It is considered probable that the SIGABA will be modified along the lines proposed by the Navy. It is proposed that all SIGABA 1s be modi fied at this Headquarters before shipment is made to the field, thus in creasing the work load as follows: EQUIPMENT MAN HOURS REQUIRED 3241 SIGABA 12 The above figure of' twelve hours per machine is an estimate based on preliminary studies of' the proposed change. It may be possible to greatly reduce this total af'ter the changes have been f inaJ.ly agreed on by the .Army and the Navy, and time studies can be made under actual conditions. ,3. In order to properly preserve these equipments while in extended storage, it is recommended that the proposals set .forth in a memorandum to the Chief, Security Division, 4 December 1945, subject "Preparation of Declassified and approved for release by NSA on 01-16-2014 pursuantto E .0. -

OBITUARY 307 Obituary Sir Erik Christopher Zeeman FRS 1925–2016

OBITUARY 307 Obituary Sir Erik Christopher Zeeman FRS 1925–2016 Christopher Zeeman was born in Japan on 4 February 1925 to a Danish father, Christian, and British mother, Christine. When he was one year old, his parents moved to England. He was a pupil at the independent school Christ's Hospital, in Horsham, West Sussex. Between 1943 and 1947 he was a flying officer in the Royal Air Force. In a career change that was to have major impact on British mathematics, he studied the subject at Christ's College, Cambridge University, graduating with an MA degree. He then carried out research for a PhD at Cambridge, supervised by the topologist Shaun Wylie. His topic was an area of algebraic topology, which associates abstract algebraic structures (‘invariants’) to topological spaces in such a way that continuous maps between spaces induce structure-preserving maps between the corresponding algebraic structures. In this manner, questions about topology can be reduced to more tractable questions in algebra. His thesis combined two such invariants, homology and cohomology, which go back to the seminal work of Henri Poincaré at the start of the 20th century.* The result was named dihomology. He introduced an important technical tool to extract useful information from this set-up, now known as the Zeeman spectral sequence. His work led Robert MacPherson and Mark Goresky to invent the basic notion of intersection homology; these ideas in turn led to proofs of some major conjectures, including the Kazhdan–Lusztig conjectures in group representation theory and the Riemann–Hilbert correspondence for complex differential equations. -

Simply Turing

Simply Turing Simply Turing MICHAEL OLINICK SIMPLY CHARLY NEW YORK Copyright © 2020 by Michael Olinick Cover Illustration by José Ramos Cover Design by Scarlett Rugers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-943657-37-7 Brought to you by http://simplycharly.com Contents Praise for Simply Turing vii Other Great Lives x Series Editor's Foreword xi Preface xii Acknowledgements xv 1. Roots and Childhood 1 2. Sherborne and Christopher Morcom 7 3. Cambridge Days 15 4. Birth of the Computer 25 5. Princeton 38 6. Cryptology From Caesar to Turing 44 7. The Enigma Machine 68 8. War Years 85 9. London and the ACE 104 10. Manchester 119 11. Artificial Intelligence 123 12. Mathematical Biology 136 13. Regina vs Turing 146 14. Breaking The Enigma of Death 162 15. Turing’s Legacy 174 Sources 181 Suggested Reading 182 About the Author 185 A Word from the Publisher 186 Praise for Simply Turing “Simply Turing explores the nooks and crannies of Alan Turing’s multifarious life and interests, illuminating with skill and grace the complexities of Turing’s personality and the long-reaching implications of his work.” —Charles Petzold, author of The Annotated Turing: A Guided Tour through Alan Turing’s Historic Paper on Computability and the Turing Machine “Michael Olinick has written a remarkably fresh, detailed study of Turing’s achievements and personal issues. -

![The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War [ Changed 26Th November 1996 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0237/the-influence-of-ultra-in-the-second-world-war-changed-26th-november-1996-2180237.webp)

The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War [ Changed 26Th November 1996 ]

The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War [ Changed 26th November 1996 ] Last year Sir Harry Hinsley kindly agreed to speak about Bletchley Park, where he worked during the Second World War. We are pleased to present a transcript of his talk. Sir Harry Hinsley is a distinguished historian who during the Second World War worked at Bletchley Park, where much of the allied forces code-breaking effort took place. We are pleased to include here a transcript of his talk, and would like to thank Susan Cheesman for typing the first draft and Keith Lockstone for adding Sir Harry's comments and amendments. Security Group Seminar Speaker: Sir Harry Hinsley Date: Tuesday 19th October 1993 Place: Babbage Lecture Theatre, Computer Laboratory Title: The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War Ross Anderson: It is a great pleasure to introduce today's speaker, Sir Harry Hinsley, who actually worked at Bletchley from 1939 to 1946 and then came back to Cambridge and became Professor of the History of International Relations and Master of St John's College. He is also the official historian of British Intelligence in World War II, and he is going to talk to us today about Ultra. Sir Harry: As you have heard I've been asked to talk about Ultra and I shall say something about both sides of it, namely about the cryptanalysis and then on the other hand about the use of the product - of course Ultra was the name given to the product. And I ought to begin by warning you, therefore, that I am not myself a mathematical or technical expert. -

Communication Intelligence and Security, William F Friedman

UNCLASSIFIED DATE: 26 April 1960 NAME: Friedman, William F. PLACE: Breckinridge Hall, Marine Corp School TITLE: Communications Intelligence and Security Presentation Given to Staff and Students; Introduction by probably General MILLER (NFI) Miller: ((TR NOTE: Introductory remarks are probably made by General Miller (NFI).)) Gentleman, I…as we’ve grown up, there have been many times, I suppose, when we’ve been inquisitive about means of communication, means of finding out what’s going on. Some of us who grew up out in the country used to tap in on a country telephone line and we could find out what was going on that way—at least in the neighborhood. And then, of course, there were always a few that you’d read about in the newspaper who would carry this a little bit further and read some of your neighbor’s mail by getting at it at the right time, and reading it and putting it back. Of course, a good many of those people ended up at a place called Fort Leavenworth. This problem of security of information is with us in the military on a [sic] hour-to-hour basis because it’s our bread and butter. It’s what we focus on in the development of our combat plans in an attempt to project these plans onto an enemy and defeat him. And so, we use a good many devices. We spend a tremendous amount of effort and money in attempting to keep our secrets in fact secret—at least at the echelon where we feel this is necessary. -

Responding to the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Business

THE 4TH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION Responding to the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Business MARK SKILTON & FELIX HOVSEPIAN The 4th Industrial Revolution “Unprecedented and simultaneous advances in artifcial intelligence (AI), robotics, the internet of things, autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, nanotechnology, bio- technology, materials science, energy storage, quantum computing and others are redefning industries, blurring traditional boundaries, and creating new opportuni- ties. We have dubbed this the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and it is fundamentally changing the way we live, work and relate to one another.” —Professor Klaus Schwab, 2016 Mark Skilton · Felix Hovsepian The 4th Industrial Revolution Responding to the Impact of Artifcial Intelligence on Business Mark Skilton Felix Hovsepian Warwick Business School Meriden, UK Knowle, Solihull, UK ISBN 978-3-319-62478-5 ISBN 978-3-319-62479-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62479-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017948314 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2018 Tis work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Te use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Books in Brief Deaths Are Greatly Exaggerated

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT Pennington argues that predictions of a coming antibiotics Armageddon leading to a substantial increase in infection-related Books in brief deaths are greatly exaggerated. On this point, I take a more cautious line. It is true that Prof: Alan Turing Decoded careful management and aseptic technique Dermot Turing ThE HISToRY PRESS (2015) can have an important role in husbanding a Computing pioneer Alan Turing has been justly and amply lauded, dwindling supply of drugs effective against not least in these pages (see Nature 515, 195–196 (2014) and nature. the most serious infections. However, Pen- com/turing). Now, a biography by his nephew, Dermot Turing, offers nington does not devote sufficient space to new sources and a refreshingly familial tone. We see the stubbornly the factors that have led the antibiotic-devel- original young Alan finding his way in maths and society; mentors opment pipeline to dry up in recent years. such as Max Newman, who kick-started Turing’s obsession with He almost trivializes the difficulties in iden- machines; the design of the electromechanical ‘bombe’ that helped tifying relevant natural products or chemical to crack the Enigma cipher; and a sensitive reappraisal of Turing’s constructs and developing them into usable suspected suicide. A measured portrait at ease with its subject. drugs, simply writing: “New antimicrobials will be very welcome. Getting them ready for rollout will be expensive and will take years.” The Cabaret of Plants: Botany and the Imagination And he skates over structural problems in the Richard Mabey PRoFILE (2015) pharmaceutical industry: we urge pharma to As a celebrant of the botanical, Richard Mabey has few peers. -

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in Cryptologia

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in Cryptologia Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 04 September 2021 Version 3.64 Title word cross-reference 10016-8810 [?, ?]. 1221 [?]. 125 [?]. 15.00/$23.60.0 [?]. 15th [?, ?]. 16th [?]. 17-18 [?]. 18 [?]. 180-4 [?]. 1812 [?]. 18th (t; m)[?]. (t; n)[?, ?]. $10.00 [?]. $12.00 [?, ?, ?, ?, ?]. 18th-Century [?]. 1930s [?]. [?]. 128 [?]. $139.99 [?]. $15.00 [?]. $16.95 1939 [?]. 1940 [?, ?]. 1940s [?]. 1941 [?]. [?]. $16.96 [?]. $18.95 [?]. $24.00 [?]. 1942 [?]. 1943 [?]. 1945 [?, ?, ?, ?, ?]. $24.00/$34 [?]. $24.95 [?, ?]. $26.95 [?]. 1946 [?, ?]. 1950s [?]. 1970s [?]. 1980s [?]. $29.95 [?]. $30.95 [?]. $39 [?]. $43.39 [?]. 1989 [?]. 19th [?, ?]. $45.00 [?]. $5.95 [?]. $54.00 [?]. $54.95 [?]. $54.99 [?]. $6.50 [?]. $6.95 [?]. $69.00 2 [?, ?]. 200/220 [?]. 2000 [?]. 2004 [?, ?]. [?]. $69.95 [?]. $75.00 [?]. $89.95 [?]. th 2008 [?]. 2009 [?]. 2011 [?]. 2013 [?, ?]. [?]. A [?]. A3 [?, ?]. χ [?]. H [?]. k [?, ?]. M 2014 [?]. 2017 [?]. 2019 [?]. 20755-6886 [?, ?]. M 3 [?]. n [?, ?, ?]. [?]. 209 [?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?]. 20th [?]. 21 [?]. 22 [?]. 220 [?]. 24-Hour [?, ?, ?]. 25 [?, ?]. -Bit [?]. -out-of- [?, ?]. -tests [?]. 25.00/$39.30 [?]. 25.00/839.30 [?]. 25A1 [?]. 25B [?]. 26 [?, ?]. 28147 [?]. 28147-89 000 [?]. 01Q [?, ?]. [?]. 285 [?]. 294 [?]. 2in [?, ?]. 2nd [?, ?, ?, ?]. 1 [?, ?, ?, ?]. 1-4398-1763-4 [?]. 1/2in [?, ?]. 10 [?]. 100 [?]. 10011-4211 [?]. 3 [?, ?, ?, ?]. 3/4in [?, ?]. 30 [?]. 310 1 2 [?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?]. 312 [?]. 325 [?]. 3336 [?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?]. affine [?]. [?]. 35 [?]. 36 [?]. 3rd [?]. Afluisterstation [?, ?]. After [?]. Aftermath [?]. Again [?, ?]. Against 4 [?]. 40 [?]. 44 [?]. 45 [?]. 45th [?]. 47 [?]. [?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?]. Age 4in [?, ?]. [?, ?]. Agencies [?]. Agency [?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?]. -

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources

1 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources “Alan Turing's Trial Charges and Sentences, 31 March 1952.” Alan Turing: The Enigma, Andrew Hodges, https://www.turing.org.uk/sources/sentence.html. This source is an image from the Alan Turing: The Enigma website depicting the arrest and sentencing record of Alan Turing and his lover Arnold Murray from 1952. This primary source shows off the fact that Turing stood strong against the charges of “indecency” that were leveled his way due to his sexuality and pleaded guilty. It interested our group to find out that Murray received a much lighter sentence than Turing for the same “crime” “A Memoir of Turing in 1954 from by M.H. Newman.” The Turing Digital Archive, King's College, Cambridge, http://www.turingarchive.org/viewer/?id=18&title=Manchester Guardian June 1954. This source is a primary source image from The Turing Digital Archive containing newspaper clippings of Turing’s obituary and an appreciation article. These images helped us to understand the significance that Alan Turing had to society at the time of his death, giving us a starting point to observe how the legacy of Turing grew after his death, as well as the impact his life had even after it came to a close. “AMT Aged 16, Head and Shoulders.” The Turing Digital Archive, King's College, Cambridge, http://www.turingarchive.org/viewer/?id=521&title=4. This image of Alan Turing as a young man helps us depict his life as a story rather than a disconnected series of events. We included it because we felt that it was important to discuss Turing’s early years and education as well as his work on Enigma and his personal life in order to present the full story to the best of our ability on our website.